Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

America's Exceptional Values

(2/9/01)

The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.

Epigraph from Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness"

The decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness. Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the causes of destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest. Cold, poverty, and a life of danger and fatigue fortify the strength and courage of barbarians.

Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

*****

We're No. 1!

The notion that Western civilization is better and American civilization is best persists. As a theory, it goes by the name exceptionalism—as in "we're exceptional and you're not." Our politicians, particularly those from the Ronnie "City on a Hill" Reagan camp, hold this view wholeheartedly.

For instance, at LA's Shadow Convention in July, 2000, Sen. John McCain said:

I believe in American exceptionalism. I believe we were meant to transform history. I believe that the progress of all humanity will depend, as it has for many years now, on the global progress of American interests and values. I believe we are still the last, best hope of earth.

How the doctrine of American exceptionalism evolved is too involved to go into here. For background on the subject, see:

American exceptionalism (The FreeDictionary.com)

American exceptionalism (GSEIS, UCLA)

A look at American exceptionalism (Rationalist.com)

It seems the idea of American exceptionalism is not so much manifested in an actual difference between the US and other countries in terms of outward behaviour, but more in terms of a ‘truth' about the mental and moral superiority of Americans being actively reiterated by American culture to the American public via movies, television and political rhetoric. To generalise, all Americans are told every day in the media that only they know how the world really works, and only they know how it should be worked. In this way, the myth is kept alive.

It has been said that the US does not have an ideology, it is an ideology. One needs only to look at the ubiquitous American flag to realise that there might be some truth in this. US culture is riddled with patriotism, and too often it is not a ‘clean' patriotism, in that pride is felt about the United States in and of itself, but rather a ‘dirty' patriotism wherein everything that is not American is actively put down, ‘dumbified' or ridiculed.

A nation apart (The Economist)

American Exceptionalism -- Selected Resources (Questia)

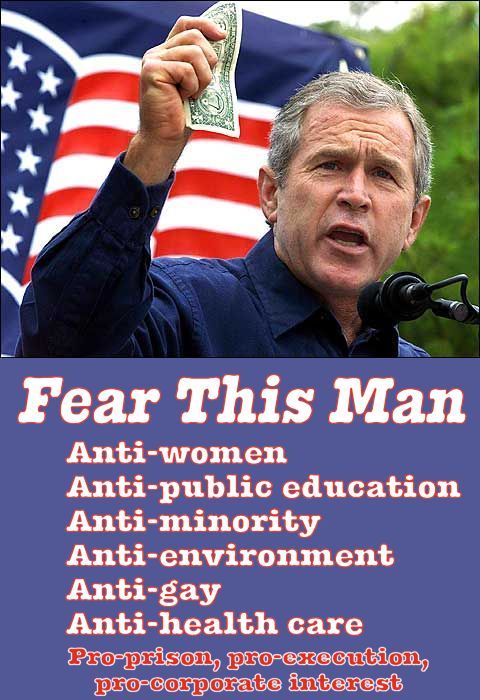

Bush isn't an exception

Unfortunately, "President" George W. Bush and Secretary of State Colin Powell share this exceptionalist position, as Powell has made clear in speeches. ("Powell Puts the U.S. on Pedestal, Observers Say," LA Times, 1/28/00.) Many observers have explained why this position is wrongheaded and dangerous:

Secretary of State Colin Powell's views on "exceptionalism" and America's superiority are dangerously self-delusionary. He may see his role as the promulgation of the refined American way across the world, but the rest of the world is unlikely to be receptive.

What is there to emulate about American democracy after the controversy and incompetence exhibited in Florida? Should foreign electoral commissions follow this model? Should other countries emulate the American way when it comes to firearms deaths, the blight of drugs in inner cities, the expense of health care or neglect of public infrastructure? Powell needs to get out more. He'll see that other countries have perfectly satisfactory economic, social and political systems and that they haven't used America 101 textbooks to get there. I would like to see an America that was humble enough to learn lessons from the rest of the world. Then the rest of the world might be a little more interested in accommodating this country's rampant ego.

Grahame Lynch, letter, LA Times, 1/31/01

The word for this might be unilateralism—a superpower that openly proclaims that it recognizes no interests except its own. The so-called Powell Doctrine, named for Colin Powell himself, states with beautiful simplicity that the United States reserves the right to act only in its own interests, to do so with overwhelming force, and to disregard any tedious legalisms that might stand in its way. (This also exempts the United States from participating in bleeding-heart humanitarian missions it doesn't like.) Currently, a version of the same doctrine is being wheeled out in order to demolish the most important treaty that the United States actually did sign—the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, forbidding the development of shields such as the Star Wars fantasy. Ah, say the Bush people, we didn't sign that treaty with Russia. We signed it with the Soviet Union! (And they like to mock Clinton's tricky way with words.)

Christopher Hitchens, Rogue Nation USA, Mother Jones, May/June 2001

America trails the pack

To Lynch's list of things not to emulate, we could add a few big ones. Life expectancy, infant mortality rates, literacy, education scores, per capita income...if you think the US is on top in each of these categories, think again.

As Lynch observes, the most exceptional thing about America is its arrogance and ego. We're also exceptionally crass, puritanical, and self-absorbed, and exceptionally oblivious to others' deprivation, lack of resources, and human rights violations. Not exactly a perfect model, eh?

Let's summarize America's exceptional history. Random chance favored the North American continent with geography, climate, and natural resources. The Europeans didn't make these advantages; they weren't even aware North America existed. They bumbled onto it while seeking a route to Asia.

Once Euro-Americans saw a gold mine (literally and figuratively) before them, they enslaved or killed the native inhabitants and imported cheap slave labor from Africa. After wars against the British, Mexicans, Indians, and Spanish, they annexed the spoils of their conquests. They did exactly as Nazi Germany later did with most of Europe and Israel did with Palestine.

They then began exporting their exceptional values by overthrowing legitimate governments and setting up puppet regimes in Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, and the Far East. At home they began deforesting and denuding the land, decimating its animal species, and dousing the air and water with chemicals. As for their promises of liberty and justice for all, it took almost 200 years and a civil rights revolution enforced by the National Guard to grant these so-called values to much of the population.

America's promises are still unfulfilled, as everything from the income gap between rich and poor to the unequal funding of schools to the disparate execution rates on Death Row prove. Now "President" Bush would fulfill these promises by...giving tax cuts to his fellow members of the rich upper class? Drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, aka the American Serengeti? Building a military strong enough to impose our views on others, along with an unnecessary and unworkable missile defense system?

Yes, it seems fair to say, America's "exceptional" values haven't changed. We still think it's our manifest destiny to dominate the world.

More on America's "greatness"

The best country in the world (hint: it isn't the USA)

Exceptional bellicosity

How are "President" Bush and Secretary of State Powell implementing their belief in American exceptionalism? From the LA Times, 3/27/01:

Bush Team's Tough Talk on Foreign Policy Alarms Experts

By ROBIN WRIGHT, Times Staff Writer

WASHINGTON—America's foreign policy community is increasingly anxious about the Bush administration's abrupt, tough-guy approach to several of the key challenges facing the United States. Many also charge that Washington may jeopardize key initiatives that are shaping the post-Cold War era.

In the latest public appeal, a coalition of top foreign policy specialists sent a letter to President Bush on Monday asking the new administration to resume diplomatic initiatives with North Korea. But the alarm spans a gamut of issues and the political spectrum.

"The foreign policy community is very anxious about Bush policy because it sees a rising level of rhetoric on China, going from 'strategic partner' to 'competitor'; refusing to negotiate with the North Koreans; some very tough statements on Russia; a total rejection of climate control negotiations; and an emphasis in talks with all parties about missile defense," said Lee Hamilton, director of the Smithsonian Institution's Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Hamilton, former chairman of the House International Relations Committee, is a Democrat but is widely respected by people in both parties.

"This is all having a very unsettling impact on the international foreign policy community as well as heads of state," he added.

The White House approach is all the more striking because of the Bush foreign policy team's pledge to show humility in its dealings with the outside world. In his only major campaign speech on foreign policy, given at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library on Nov. 19, 1999, Bush called for a foreign policy that reflected American character, especially "the humility of real greatness."

And in his debut speech at the State Department last month, the president told America's diplomatic corps that his goal was to turn an era of American preeminence into generations of democratic peace, which would require the United States "to project our strength with purpose and with humility."

Yet only nine weeks into Bush's term, his administration's approach to foreign policy has been described by leading analysts as defiant.

James Hoge, editor of Foreign Affairs magazine, expressed concern Monday about "schoolyard bellicosity" so early in a new presidency.

"Why are they so interested in saying to Russia that it's mismanaging things, that it's not that important anymore, that they'll take its views into account but not treat them all that seriously? I'm mystified by it," he said. "What can they possibly gain from this kind of schoolyard bellicosity at this stage?"

They can feel good about how tough they're acting, of course.

What exactly is Hoge's problem? Bush is doing pretty well by my reckoning. He's batting .500.

True, he lied about being humble, but lying ("read my lips") seems to run in the Bush family. What matters is that Bush's foreign policy reflects America's exceptional values. "Schoolyard bellicosity" is exactly what the American character is all about, and Bush and Powell are doing an excellent job of proving it.

America knows best?

Confirming America's exceptionalism in his own fractured way, Bush lectured German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, a statesman with much more world experience, on 3/30/01. The subject was why Bush and America have the "right" to break their promise to uphold the Kyoto global warming protocols, a treaty the US signed in 1997:

I will consult with our friends. We will work together. But it's going to be in, what's in the interest of our country, first and foremost.

I will explain as clearly as I can, today and every other chance I get, that we will not do anything that harms our economy. Because first things first are the people who live in America. That's my priority.

To Bush, "first things first" means economic wealth. Nice of him to consult with other world leaders on how to keep Americans richer and more powerful than everyone else, isn't it?

Gosh. A conservative leader who exalts profits over people. An American leader who breaks a valid treaty because Anglo-Americans come first. A conservative, American leader who puts short-term considerations before the health and welfare of the next seven generations.

If you're a Native American, or any American, who's heard this one before, please raise your hand.

More on Bush's lack of humility

Bush's reputation is "as a man whose esteem for himself is too high and regard for others too low."

Bush is hardly the only selfish, narrowminded American leader in American history. He's merely the latest. Charles Ingrao, Professor of History at Purdue University, notes several recent examples of Americans putting expedience ahead of principle. From the LA Times, 4/3/01:

[T]he United States...often has been selective in applying its formidable financial resources, diplomatic leverage and intelligence capability to the cause of international justice. Since the beginning of the Cold War, Washington has downplayed or ignored crimes committed by its allies and by countries with whom it seeks a working relationship. Hence the disinterest in large-scale atrocities committed by fiercely anti-Communist regimes in Leopoldo Galtieri's Argentina, Suharto's Indonesia and Turkish Kurdistan; the delay in prosecuting the murderous Pol Pot regime in Cambodia while it served as a useful counterpoise to communist Vietnam; and the decision not to pursue Saddam Hussein in deference to Arab allies. Basically, no crime committed anywhere in the world can come to a U.N. criminal tribunal if it contradicts the national interest of the U.S. or another major power.

One could go through a long list of 20th-century examples: from setting up banana republics in Central America to ignoring the Holocaust to putting the Shah on the throne in Iran to overthrowing Allende in Chile to propping up Marcos in the Phillippines. Yes, America believes in liberty and justice for all—except when oppression, totalitarianism, and genocide benefit us more.

More on America's commitment to doing the right thing

Amnesty International: "[T]he United States is as frequently an impediment to human rights as it is an advocate."

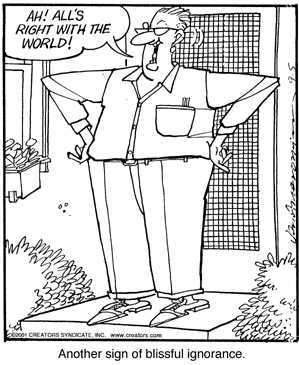

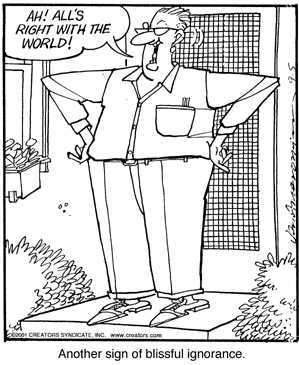

Is ignorance a value?

From a travel column by Mike McIntyre in the LA Times, 12/31/00:

You can learn a lot about your country by leaving it. I used to think most criticism of America sprang from jealousy, but now I believe it's born of bafflement. Many around the world see us as work-obsessed and materialistic.

It's an unfair world. We can't choose our parents. Where we're born is a cosmic crapshoot. Americans, even the poorest among us, are born with advantages most others will never know. Don't leave these shores if you can't face how good you've got it. You'll find almost unimaginable poverty and suffering, endured by people who never had a chance. Every day I was forced to admit, there but for sheer, dumb luck go I.

The most notable thing about McIntyre's "revelation" may be that he didn't realize the situation until he left home. He confirms that Americans are ignorant or shortsighted about the world around them. And, since they live happily while the rest of humanity suffers, that their much-vaunted compassion and charity extend only so far.

We Americans are glad to help others—as long as it doesn't inconvenience us or cost us anything, furthers our self-interested agenda, and solidifies our position as world leader. Why? Because, like all the self-appointed kings, popes, and prophets before us, we're the exception.

A bit harsh? Here's a thought experiment for you. If you're an American who believes in democracy, would you be willing to put the Kyoto global warming treaty, the World Trade Organization's trade rules, or the Third World's debt repayment obligations to a vote? A vote of all the world's people, that is, with the United States bound to obey the will of the majority?

No? Then you don't really believe in democracy, do you? What you believe in is democracy for you but autocracy for others. As an American, you think you can set the rules and others can't vote to change them.

This isn't even a thought experiment anymore. Showing its disgust with America's values, the rest of the world voted the US off the UN's Human Rights Commission and International Narcotics Control Board. As the LA Times reports, 5/4/01:

Human rights groups say there has been growing resentment toward the U.S. among Western nations that are usually its allies, as well as among developing countries, because of recent American votes opposing key human rights initiatives.

"This has been coming. It should not have been a surprise to Washington," said Joanna Weschler, the U.N. representative of Human Rights Watch. "They've voted alone, on the wrong side of several important issues."

The U.S. has opposed treaties to abolish land mines, does not support the International Criminal Court and abstained from a vote to make more widely available drugs to combat the AIDS pandemic.

Adding to the atmosphere of frustration with the U.S. were other recent unilateral actions by the Bush government, such as pulling out of the 1997 climate treaty reached at Kyoto, Japan, and the administration's insistence on developing a national missile defense system despite widespread opposition from allies as well as other nations.

"This is their wake-up call," Weschler said. "We hope this will prompt a review of their policies."

And from the LA Times, 5/8/01:

"I think there's a sock-back for the unilateralism and the allergies to treaties that this administration is developing," said former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright. "People are concerned about several unilateral moves the United States has taken recently."

The list of such acts is long and growing. The latest was President Bush's speech last week on missile defense. After promising to consult with allies before he took any major step, he instead signaled his intention to withdraw the United States from the Antiballistic Missile Treaty—and only this week dispatched teams around the world to explain the move and the administration's plans for an alternative approach to defense.

Since our recent moves have earned near-universal opprobrium from other nations, would it now be fair to call America the world's No. 1 rogue state?

Conservatives scorn democracy

How did America's ruling class—those patriotic lovers of democracy, free votes, and fair play known as conservatives—respond to this democratic outcome? Led by House Republicans, they childishly voted to withhold our UN dues, which we're obligated to pay by treaty. So much for our culture's belief in democracy.

Just think about Congress trying to coerce a result with financial pressure. Does anything exemplify our selfish and materialistic mindset better? Given a choice, Americans will always favor dollars over democracy...riches over right and wrong.

As this example proves, the American mentality is the gunslinger mentality all over again. He who slings the gun, rules. Might (physical or financial) makes right.

Did John Wayne ever consult with anyone, negotiate or compromise, or cede power to his "inferiors"? I don't think so.

Death to our exceptional values?

If Joanna Weschler of Human Rights Watch expected America to change, she must've been disappointed. Metaphorically speaking, "President" Bush slept through his wake-up call. His response to the UN Human Rights Commission shocker was to vote alone with Somalia, that other paragon of virtue, against children's rights. He also withdrew from the World Conference Against Racism when the attendees tried to discuss America's exceptional values—such as its longstanding racism and imperialism.

Perhaps fed up with the American-led Westernization of the world, terrorists struck brutally at America on 9/11/01, killing thousands at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. People around the globe expressed sorrow for the loss of life but said Americans could've expected an attack. "If the U.S. prefers to pretend that it rules the world," observed a Russian legislator, "such myopia will continue to result in horrible acts of terror."

Or as Ward Churchill (self-proclaimed Creek/Cherokee) wrote in Some People Push Back: On the Justice of Roosting Chickens:

America's indiscriminately lethal arrogance and psychotic sense of self-entitlement have long since given the great majority of the world's peoples ample cause to be at war with it.

The initial response was typically American. US citizens and leaders alike trampled their commitment to liberty and justice in their rush to judgment. The world's "moral leaders" demanded solutions ranging from annihilation to extermination to mere destruction. (Genocide has always been a key American value.) Cooler heads called for vengeance and death only against targeted individuals.

Forgetting such non-American values as "Love your enemies," alleged Christian Bush declared war on, well, somebody. Commentators touted America's strength and resolve as if a plane crash might infect the country like a virus. Arab Americans with no connection to terrorists were vilified, threatened, and attacked. Pundits speculated on how many civil liberties the US might discard as a luxury.

One thing is clear: America has received its wake-up call now. Because of the enormity of this crisis—a "second Pearl Harbor"—I've given it its own set of postings. Suffice it to say, America's response to the deadly slaughter will spotlight its exceptional values.

War reveals our exceptional intolerance

From the Guardian, 10/8/01:

Intolerant liberalism

The west's arrogant assumption of its superiority is as dangerous as any other form of fundamentalism

Madeleine Bunting

Monday October 8, 2001

The Guardian

The bombs have hit Kabul. Smoke rises above the city and there are reports that an Afghan power plant, one of only two in the country, has been hit. Meanwhile the special forces are on standby, and the necessary allies have been cajoled, bullied and bribed into position.

That is not all that was carefully prepared ahead of yesterday's launch of the attacks. Crucially for a modern war, public opinion formers at home have been prepared and marshalled into line with a striking degree of unanimity. The voices of dissent can barely be heard over the chorus of approval and self-rightous enthusiasm.

It's the latter that is so jarring, and it's a sign of how quickly the logic of war distorts and manipulates our understanding. War propaganda requires moral clarity -- what else can justify the suffering and brutality? -- so the conflict is now being cast as a battle between good and evil. Both Bin Laden and the Taliban are being demonised into absurd Bond-style villains, while halos are hung over our heads by throwing the moral net wide: we are not just fighting to protect ourselves out of narrow self-interest, but for a new moral order in which the Afghans will be the first beneficiaries.

The extent to which this is all being uncritically accepted is astonishing. Few gave a damn about the suffering of women under the Taliban on September 10 -- now we are supposedly fighting a war for them. Even fewer knew (let alone cared) that Afghanistan was suffering from famine. Now the west is promising to solve the humanitarian crisis that it has hugely excerbated in the last three weeks with its threat of military action. What is incredible is not just the belief that you can end terrorism by taking on the Taliban, but that doing so can be elevated into a grand moral purpose -- rather than it incubating a host of evils from Chechnya to Pakistan.

Is this gullibility? Naivety? Wishful thinking? There may be elements of these, but what is also lurking here is the outline of a form of western fundamentalism. It believes in historical progress and regards the west as its most advanced manifestation. And it insists that the only way for other countries to match its achievement is to adopt its political, economic and cultural values. It is tolerant towards other cultures only to the extent that they reflect its own values -- so it is frequently fiercely intolerant of religious belief and has no qualms about expressing its contempt and prejudice. At its worst, western fundamentalism echoes the characteristics it finds so repulsive in its enemy, Bin Laden: first, a sense of unquestioned superiority; second, an assertion of the universal applicability of its values; and third, a lack of will to understand what is profoundly different from itself.

This is the shadow side of liberalism, and it has periodically wreaked havoc around the globe for over 150 years. It is detectable in the writings of great liberal thinkers such as John Stuart Mill, and emerged in the complacent self-confidence of mid-Victorian Britain. But its roots go back further to its inheritance of Christianity's claim to be the one true faith. The US founding recipe of puritanism and enlightenment bequeathed a profound sense of being morally good. This superiority, once allied to economic and technological power, underpinned the worst excesses of colonialism, as it now underpins the activities of multinational corporations and the IMF's structural adjustment programmes.

But recognising this need not be the prelude to an onslaught on liberalism -- just the crucial imperative of recognising that, like all systems of human thought, liberalism has weaknesses as well as strengths. We need to remember this: in the heat of battle and panicky fear of terrorism, liberal strengths such as tolerance, humility and a capacity for self-criticism are often the first victims.

In all systems of human thought, there are contradictions that advocates prefer to gloss over. One of the most acute in liberalism is between its claim to tolerance and its hubristic claim to universality, which Berlusconi's comments on the superiority of western civilisation brought embarrassingly to the fore two weeks ago. It was the sort of thing many privately think, but are too polite to say, argues John Lloyd in this week's New Statesman. He owns up with refreshing honesty that in the conflict between Islam and Christianity: "Their values, or many of them, contradict ours. We think ours are better."

Once this kind of hubris is out in the open, at least one can more easily argue with it. These aren't just academic arguments for the home front before the cameras start rolling on the exodus of refugees into Pakistan. September 11 and its aftermath launched both an aggressive reassertion and a thoughtful re-examination of our culture and its values. Both will have a lasting impact on our relations with the non-western world, not just Muslim world. It is that aggressive reassertion that smacks of fundamentalism, a point obliquely made by Harold Evans recently: "What do we set against the medieval hatreds of the fundamentalists? We have our fundamentals too: the values of western civilisation. When they are menaced, we need a ringing affirmation of what they mean." The only problem is that "ringing" can block out all other sound and produce nothing but tinnitus.

There is a compelling alternative for how we can coexist on an increasingly crowded planet. Political philosopher Bhikhu Parekh starts from the premise that "the grandeur and depth of human life is too great to be captured in one culture". That each culture nurtures and develops some dimension of being human, but in that process it misses out others, and that progress will always come from dialogue between cultures. "We are all prisoners of our subjectivity," argues Parekh, and that is true of us individually and collectively, so we need others to expose our blindnesses and to increase our understanding of our humanity.

Parekh argues that liberalism is right to assert that there are universal moral principles (such as the rights of women, free speech and the right to life), but wrong to insist there is only one interpretation of those principles and that that is its own. Rights come into conflict and every culture negotiates different trade-offs between them.

To understand those trade-offs is sometimes complex and difficult. But no one culture has cracked the prefect trade-off, as western liberalism in its more honest moments is the first to admit. There is a huge amount we can learn from Islam in its social solidarity, its appreciation of the collective good and the generosity and strength of human relationships. Islamic societies are grappling with exactly the same challenge as the west -- how to balance freedom and responsibility -- and we need each other's help, not each other's brands of fundamentalism. If we are asking Islam to stamp out their fundamentalism, we have no lesser duty to do the same.

Madeleine Bunting, <m.bunting@guardian.co.uk>

Guardian Unlimited © Guardian Newspapers Limited 2001

An end to our exceptional unilateralism?

From the LA Times, 11/4/01:

FOREIGN POLICY

Bush's Unlikely Friends

By WALTER RUSSELL MEAD

Walter Russell Mead, a contributing editor to Opinion, is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of "Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World."

NEW YORK — Can this really be the Bush administration?

Since Sept. 11, we have sent troops abroad without a clear exit strategy and started nation-building in Afghanistan. Mainland China is our friend now; we are cozying up to Russian President Vladimir V. Putin. We are up to our elbows in what we used to call the Middle East peace process, which looks more like a war process now, but the U.S. is putting more and more weight on Israel to get some kind of settlement there.

Many Democrats and liberal internationalists are rubbing their hands with glee at these changes. See, they say, the Lone Ranger approach to foreign policy doesn't work. To get what it wants in the real world, the United States must cooperate with other countries, pay its U.N. dues and seek multilateral solutions to complex international problems. So has the Bush team gone soft and cuddly?

Not exactly.

The new internationalism in U.S. foreign policy is conservative, not the liberal version of the Clinton era. It isn't about universal courts for human rights, the Kyoto Protocol or international treaties on land mines. Nor is it about human rights. If China will help us stamp out international terrorism, we won't say too much about China's human rights violations. If Russia cooperates on intelligence and helps us crack down on money laundering, Washington won't make a big fuss about "collateral damage" to civilian targets in Russia's war against the Chechens.

This is the internationalism of America at war. During the Cold War, the U.S. notoriously cozied up to dictatorships and kleptocracies around the world if they would help us with our core objective of containing the Soviet Union. Fascists like Spain's Gen. Francisco Franco and Communists like Mao Tse-tung were both welcome under America's big tent in the coalition against Moscow.

Now that we have another war on our hands, it's coalition-time again. If your house is on fire and the neighbors form a bucket brigade, you don't make them pay their overdue library fines before joining in. You take their help and you thank them. Later, when the fire is out, you can go back to nagging them to mow their lawns or fix the noisy car mufflers.

So far, even people who don't like the Bush administration very much, which as of Sept. 11 was most of the world, signed up for the bucket brigade. Russia and China don't like our plans for national missile defense, and they worry that the U.S. is getting too strong and too pushy, but they like Osama bin Laden and the Taliban even less. If worse comes to worst, Russia and China know that the United States government will not attack them with nuclear or biological weapons, because, among governments, deterrence works. That kind of deterrence doesn't work as well when you are dealing with religious fanatics who can hide out in caves. Russia and China also have problems with their own Muslim minorities, and neither country wants the disease of fanaticism to spread through Central Asia.

Given all this, Russia and China honestly want us to win the war against terrorism, although they can probably stand it if we burn our fingers a little while we fight. They also won't shed many tears if the war makes us unpopular in the Arab world.

Our NATO allies are also glad to see us fighting this war. More than one European government was unhappy with our policy of supporting Muslim ethnic groups against the Serbs in the Balkans precisely because they were afraid to see Islamic governments spring up in Europe. While Muslims from the Middle East constitute only a small percentage of U.S. immigrants, they are the largest single group of immigrants across much of Western Europe. Again, while most European governments will try to win a few points in the Arab world by trying to look a little less hawkish than President Bush, at least for now their fears of fundamentalist terror far outweigh their concerns about American unilateralism.

Meanwhile, most Arab governments are going along, however nervously, because they know that the fundamentalists hate them even more than they hate us. Some countries, like Pakistan, are uneasy enough about their own past ties to terrorists and the Taliban that they are cooperating with us partly because they fear we might decide that they are part of the problem, rather than part of the solution, and act accordingly.

Like most war coalitions, the current one is a mixed bag: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. It isn't a grand Wilsonian coalition for democracy and human rights, but that doesn't mean that the cause isn't moral.

Bush is rarely silver-tongued, but when he called this a war for civilization, he was right on the money. The coalition against terrorism is one that believes in order against those of whatever religion who follow voices in their heads telling them to put anthrax in the mail. The logic is so clear that even dictators can see it. The danger is so great that if dictators are willing to help us, we will accept their help—gladly.

Wilsonians need not despair. As the war drags on, the Bush administration will have to fight harder to win the battle for international public opinion. Ultimately, we will have to do more than talk about what we are fighting against and explain what we are fighting for.

When that time comes, the conservative internationalism of today will begin to look more like the idealistic internationalism of some of our past conflicts. A greater U.S. commitment to ending global poverty, improving educational opportunities in poor countries and fighting diseases like HIV/AIDs will almost inevitably become part of America's war-fighting strategy. And just as liberals are mostly backing the conservative internationalism of this stage of the war, conservatives will back the liberal internationalism that will emerge later in the conflict.

Policeman of the world, nation-builder of the world, social worker of the world: Many Americans want us to have none of these jobs, and almost no Americans want us to have all of them. But to keep ourselves safe in the 21st century, we are going to have be good at all three.

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

Comment: Don't bet on conservatives doing anything but returning to their hidey-holes (their mansions and vacation homes and yachts) once the "war" is over. Bush already has demonstrated it's business as usual on the domestic front. Soon it'll be business as usual on the foreign front also.

The one flat note in Mead's essay is his linking the anthrax scare to the "war" on terrorism. Actually, as I predicted as far back as 10/17/01, the anthrax scare will prove to have nothing to do with the so-called war. The idea that we're protecting civilization from anthrax terrorists will be demonstrably wrong, since the terrorists will be home-grown killers raised to cherish our "civilized" values.

Bush-war proves no exception

With the war on Afghanistan ending in winter 2001 and the "war" on terrorism continuing as a police action, it's clear the Bush administration won't change its ways. Like the Reagan administration it admires and emulates, it's quintessentially American: myopic, self-serving, spurning anything that might affect its pocketbook.

From the LA Times, 7/2/02:

COMMENTARY

Happy Birthday ... Now Grow Up

An adolescent America remains a paradox in the family of nations.

By BARBARA BARNOW

Birth order invariably influences our standing in the family, and, along with our personalities as children, can cause us to be forever defined as, say, "the middle child" or "the smart one." So it is with nations.

In the context of the family of nations, it is likely that the United States will always be viewed as a young country. Our buildings and landmarks, few more than two centuries old, include no royal palaces, and our institutions lack the weathered character created by repeated political and social change. Our contributions to art, literature and music, though distinct and honored, have not been tested over time.

Compared with elder nations, we are inexperienced in traditions and history. Most probably the popular view is that our immaturity holds us back from appreciating the wisdom that emerges from long-standing religious and political struggles, many wars in the homeland and centuries of cultural bursts and upheavals. The paradox is that while we maintain the position of superpower, we do so as an adolescent—and more significantly, an adolescent with money. We display the confidence and arrogance of a 15-year-old boy. We know everything, we can do everything, we are entitled to everything and, naturally, we should be exempt from any and all consequences.

History shows that this headstrong, self-serving posturing sometimes jeopardizes our ability to maintain constant allegiances, especially when it is accompanied by aggressive actions (bombing Iraq and Afghanistan), dismissive actions (ignoring land mines and environmental issues raised by the United Nations) and irresponsible actions (selling arms to hostile countries for short-term political gains).

Unfortunately, since Sept. 11 our posturing and rhetoric, particularly related to "the axis of evil," have energized a broader and more visible disdain from foreign leaders as well as their citizens.

Yet, for all the negative reviews, our nation continues to garner respect for those characteristically adolescent qualities that have helped us prevail as a superpower. We aim high, dismissing obstacles, and we are ready to take on the world and change it. We are willing to take risks and often succeed. We are full of passion and dream big. Just like a teenager.

And in the same way that adults regard an arrogant and slightly rebellious teenager, the world views us with a mix of disdain and admiration. Other countries eye our materialism and freedom while they comment on our shallowness.

Often we are envied because we accumulate and are completely at ease with state-of-the-art technology; yet, we are also criticized for those attributes.

As we approach our nation's 226th birthday, we are reminded of the origin and course of our history. Doubtless, we will be reminded of our patriotism, newly charged since Sept. 11. Our leaders will rally us to celebrate not only our own passage to independence and democracy but also our commitment and support for these principles in other countries. Once again, we will honor ourselves as "the greatest country in the world."

So, happy birthday to the United States of America. We face a very different future than we did on our last birthday, and, according to tradition, it is time to reflect. Is it to our advantage to remain eternally adolescent, to face the challenges of terrorism and global relations with single-minded determination and resilience? Or is it time to inch into adulthood, cultivating wisdom and restraint?

Barbara Barnow is a writer in Columbia, Md.

Copyright 2002 Los Angeles Times

Exceptional again!

One year after 9/11, America is back to the status quo. We think we're exceptional, beyond history, better than everyone else. After working with other nations in its war on Afghanistan, the Bush administration once again has resumed its arrogant unilateralism.

From the letters to the LA Times, 8/5/02:

Unilateral U.S. Policies Are Hard to Explain

Re "America's Got an Image Problem, Panel Warns," July. 31: According to a report released by the Council on Foreign Relations, the U.S. is losing badly in the court of world opinion and needs to revolutionize the way it communicates its policies and ideas. Even though, as President Bush assures us, we are good people and a "force for good around the world," we are often seen as "arrogant, self-indulgent, hypocritical, inattentive.... " Conclusion: We haven't explained ourselves well enough. We need the newly established Office of Global Communications, aimed at improving the nation's image abroad.

Good heavens! Did the panel ever consider the possibility that we have a problem not of image but of substance, that in too many ways we are arrogant, self-indulgent, hypocritical and inattentive, and thus sometimes world opinion is all too justified?

Stanley R. Moore

CLAREMONT

*****

Is it any wonder that there's anti-U.S. sentiment throughout the planet? Unilateral U.S. policies since Bush took office have alienated friends, allies and much of the American public.

How can our country's arrogant attitude toward the very real crisis of global warming, with its rejection of the Kyoto agreement, win the respect of our neighbors? When we burn 25% of the world's fossil fuels with 4% of the population, how can we credibly argue against the pillaging of the rain forests? Why is the "personal freedom" of driving bloated SUVs more politically viable than environmental responsibility? How can we earn the respect of the Arab world when our bias in favor of Israel ignores the will of the U.N. and its call for the Israelis to leave the occupied territories? How can we earn the respect of the rest of the world when our foreign aid per capita is much lower than that of many less wealthy nations? On countless other issues, the U.S. has chosen to enforce its "we know best" policy because we have the economic and military might to do so. It's time for Bush to realize that arrogance has a price and that no amount of public relations can erase the real damage our attitude is doing to the global environmental and political landscape.

Richard Plavetich

LAGUNA BEACH

Articles on America's exceptional values

Understanding Our National Denial About Iraq: "It's not a rational response, it's a deep-seated emotional one."

"[Ideologues] begin from a position or belief and then construct an argument for it instead of the other way around."

Seeing Islam Through a Lens of U.S. Hubris: Our national mind-set may be leading us toward defeat, a CIA expert says.

"The drive to export our goodness has a divine-like quality and long antedates Bush."

"[T]he Bush bubble reflects a spirit deeply evangelical, more concerned with justifying and converting than questioning and learning."

[Hawks believe] "American global supremacy is possible not only because America is a uniquely just nation but because others around the globe see it as such."

Schlesinger: "Born again, Bush the younger has a messianic tinge about him. He thinks big and wants to make his mark on history."

Emperor George: "[T]his administration, and this war, are not typical of the US. On the contrary, ... they are exceptions to the American rule."

"God is on his team, [Bush] tells us, which explains why he sleeps easy. He is wrapped in the swaddling embrace of evangelical imperative...."

A Naked Bid to Redraw World Map: Sadly, Bush has made the U.S. the 21st century's first colonizer.

The Empire Needs New Clothes: "War isn't about oil, it's about maintaining the American lifestyle."

Americans are from Mars, Europeans are from Venus: "Americans generally split the world into good and evil, friends and enemies."

How the World Sees Americans: "[T]he world's superpower...has a childlike understanding of everybody else."

The Power Paradox: "[H]olding a monopoly on might...is likely to provoke a backlash."

The President's Real Goal in Iraq: "This war, should it come, is intended to mark the official emergence of the United States as a full-fledged global empire...."

More on America's exceptional values

America is no exception

American imperialism continues

Comic-book look at American empire

Why don't "they" like us?

Related links

Bush to "rid the world of evil"?

A shining city on a hill: what Americans believe

America's cultural roots

Manifest Destiny = America's pathology

America's cultural mindset

Readers respond

"Why does every other country...try to imitate our...system of government?"

"No one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American people," wrote H.L. Mencken. Apparently hoping to prove Mencken right, a reader wrote in to demonstrate just how blind, stupid, and prejudiced Americans can be. Here's the word from Boobus Americanus. (WARNING! This page contains adult language.)

"You liberal whiners howl about 'racism,' but you still want modern conveniences."

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.