Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

Why Write About Superheroes?

(8/23/01)

Myth is the secret opening through which the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into human cultural manifestation. Religions, philosophies, arts, the social forms of primitive and historic man, prime discoveries in science and technology, the very dreams that blister sleep, boil up from the basic, magic ring of myth.

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 1949

The gift of fantasy has meant more to me than my talent for absorbing knowledge.

Albert Einstein

No one has matched novelist Greene at describing the early allure of trash literature: ". . . in childhood, all books are books of divination, telling us about the future, and like the fortune teller who sees a long journey in the cards or death by water, they influence the future. I suppose that is why books excited us so much. What do we ever get nowadays from reading to equal the excitement and the revelation in those first 14 years?

"Of course, I should be interested to hear that a new novel by Mr. E.M. Forster was going to appear this spring, but I could never compare that mild expectation of civilized pleasure with the missed heartbeat, the appalled glee I felt when I found on a library shelf a novel by H. Rider Haggard. . . ."

Michael Sragow, "It May Be Trash, but It's Not Garbage," LA Times, 6/30/01

The British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead said that to understand a culture, one must study its second-rate literature. First-rate stuff, he said, is too good. It offers transcendent truths applicable to all times, to all places; that's why Shakespeare still holds up, centuries and oceans away from Olde England. By contrast, second-rate literature is rooted in the moment, so it's a cultural snapshot.

James Pinkerton, LA Times, 8/22/02

Science fiction has often been called pop culture's answer to metaphysics, a secular way to explore the myth of transcendence. Spielberg believes this, and it is probably why "E.T." is his most popular film. "Science fiction does not have to go very far to connect with the spiritual," he says. "Science fiction is about pure imagination, about dreaming. And imagination and dreaming are as close to basic beliefs as anything we can cherish."

From an article on Steven Spielberg's A.I., LA Times, 5/6/01

Superheroes as science fiction and fantasy

As Spielberg said, "Science fiction is about pure imagination, about dreaming." This is true of the related field of fantasy as well. A pop product like Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, or E.T. is as much fantasy as it is science fiction.

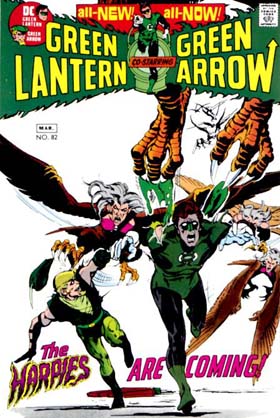

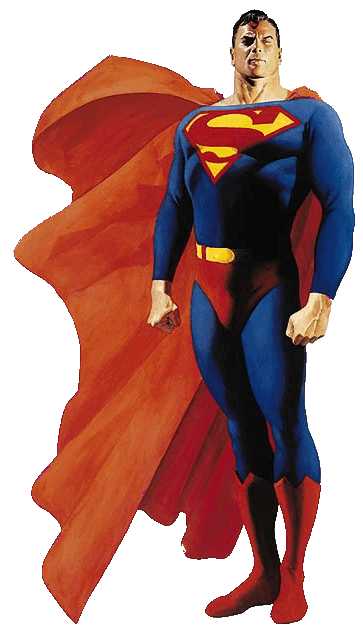

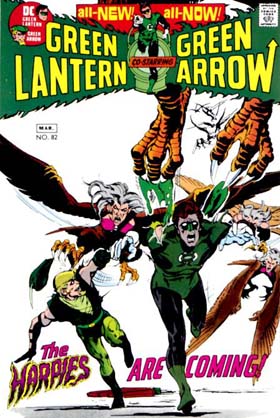

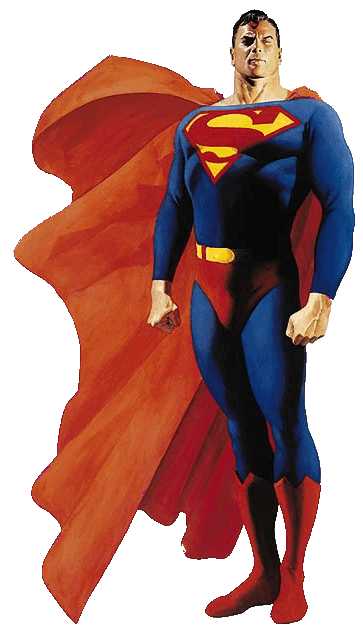

Superheroes are a distillation of both science fiction and fantasy, usually set in today's gritty world. You have your science heroes (Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, Hulk, Fantastic Four, X-Men) and your fantasy heroes (Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, Thor, the original Green Lantern, Sandman, Swamp Thing). Either way, you're implicitly, sometimes explicitly, addressing the fundamental questions of belief. If you don't understand that, you probably don't understand why superheroes are so popular.

Beneath what seem to be purely commercial considerations, the need to mentally prepare for disasters is precisely what prompts the creation of such action adventure and post-apocalyptic tales. People have always used storytelling to try to make sense of life and death, says L.A. psychotherapist and former screenwriter Dennis Palumbo. "People feel small and impotent in the face of social and technological advances. And so we try to harness our anxiety by dramatizing the worst-case scenarios," he said. "In these type of stories, there is an inherent control, by the creator, if nothing else."

Mary McNamara and Reed Johnson, LA Times, 9/12/01

All the great heroes of popular fiction—Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, the Lone Ranger, the Shadow, James Bond, Mr. Spock—are essentially superheroes, whether they wear a costume or not. So are the classic heroes from myth and legend: Gilgamesh, Moses, Hercules, Krishna, Beowulf, King Arthur. The continuity is clear, which is why gods, knights, and gunslingers keep reappearing as heroes and superheroes.

Trite and repetitive superhero comics may fade away and die. But superheroes as a genre? As Joseph Campbell and others have written, much better than I could, the mythic (super)hero will always be with us.

Let's look at the connections between three classes of characters: gods and other mythological figures; cowboys; and superheroes. First, the Greek hero and the American cowboy.

*****

Gods and cowboys

The Western ideal of a hero began in Greece with human-like gods and god-like humans. As Thomas S. Engeman explains in In Defense of Cowboy Culture, 5/28/03:

In "Democratic Vistas," Walt Whitman argued that a heroic literature is necessary for a heroic people. According to Whitman, the Homeric epics provided that noble standard for Greeks and Romans, as the Arthurian legends did for later Europeans. To become a great nation, America had to create an equally noble, albeit democratic, literature. For "[great] literature penetrates all, gives hue to all, shapes aggregates and individuals, and, after subtle ways, with irresistible power, constructs, sustains, demolishes at will…. Greece immortal lives in a couple of poems." The democratic hero of American popular culture has a pre-history, then, out of which he emerged and from which he must be distinguished.

We can consider the archetypal knight—a sword-wielding hero—as a pre-industrial version of the cowboy. Or perhaps the knight deserves a separate category as a transitional hero between the gods/demigods and cowboys. Engeman lends support to this position:

The chivalric romances were as important to Whitman as the Homeric epics. Like the frontier myth in America, Arthurian poetry was self-consciously nostalgic. It renewed (or created) the memory of a golden age, the better to hearten its people to war anew. In Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (1485), the standard source for later versions of the Arthurian legends, Malory's knights differ little from Homer's heroes. If formally Christian, and allies of King Arthur, they too do pretty much as they please. Independent landholders, the knights freely withdraw from Arthur's service whenever it suits them. Moreover, Arthur causes the civil war within his loosely organized company by attacking his greatest knight, Sir Lancelot, for his too open dalliance with Queen Guinevere. Here the parallel with Homer is clear. The Trojan War began with Paris's abduction of Helen, even as the later conflict among the Achaeans results from "King" Agamemnon's jealousy at Achilles' possession of the beautiful concubine Briseis. But Malory combined these pagan themes with the great, countervailing Christian theme of the Grail quest, first described by the French poet Chretien De Troyes. According to this new legend, Christ served the Last Supper from the Holy Grail, and it received the blood from His wound on Calvary; a vision of the Grail was tantamount to becoming one with the Savior. The Grail knights selflessly pursued justice in order to obtain spiritual purity, not women, wealth, and lands.

In any case, the knightly figure used the best weapons technology of the time to impose his version of order and justice. There are many examples of these proto-cowboys in legend and fiction: King Kull, Conan, Elric, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, Beowulf, King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, Roland, the Three Musketeers, the Scarlet Pimpernel, Zorro, Edgar Rice Burroughs's swordsmen, Errol Flynn's pirates, Tolkien's Aragorn, Tarl Cabot, Dray Prescott.

Engeman then explains how the knight transmuted into the early American cowboy—the pioneer or frontiersman—embodied by Natty Bumppo, aka Hawkeye:

Almost four centuries later, Sir Walter Scott mined a similarly heroic chapter in English history. In Ivanhoe, Scott revives the Saxon-Norman conflict over the rule of England. In contrast to Norman tyranny and moral corruption, the Saxon Ivanhoe is a gentleman. Against the previous heroic tradition, Ivanhoe rejects the right of the powerful to possess the fair. In Scott's more Protestant and democratic England, there is no natural right of the strong to rule over women and the property of the weak. But unlike the American hero, Ivanhoe fights to establish himself within the nobility. He is betrothed to the daughter of a great Saxon lord, and fights to restore his own lord, King Richard, to the throne of England.

Beginning three years after the publication of Ivanhoe in 1820, James Fenimore Cooper created the first American, democratic version of the knight-hero in his five Leather-Stocking novels— a hero called variously Natty Bumppo, Deerslayer, Hawkeye, or Leather-Stocking. Natty's character is most fully developed in the last of these sagas, The Pathfinder (1840) and The Deerslayer (1841). In addition to his superhuman fortitude, incomparable martial skills, and perfect knowledge of the wilderness, Natty is a true Christian. He avers that "a man without conscience is but a poor creatur'…. I trouble myself but little with dollars…if a man has a chest filled with [them], he may be said to lock up his heart in the same box." While Natty serves in the church of nature, he is also schooled in the formal tenets of his faith. "I eat in church, drink in church, sleep in church. The 'arth is the temple of the Lord, and I wait on him hourly, daily, without ceasing, I humbly hope. No-no-I'll not deny my blood and colour, but am Christian born, and shall die in the same faith" (emphasis added). Written near the peak of the Second Great Awakening, these novels stress Natty's chivalric and Christian qualities. In The Last of the Mohicans, Natty learns the art of war from the Indians in the same way young squires once trained to be knights. The heroic Bumppo even surpasses his teachers in martial prowess. Killdeer is the best rifle on the frontier, and Natty is a superhuman marksman. Above all, Leather-Stocking is the Chosen One. A friend observes: "the man will never die by a bullet. I have seen him so often, handling his rifle with as much composure as if it were a shepherd's crook, in the midst of the heaviest showers of bullets, and under so many extraordinary circumstances, that I do not think Providence means he should ever fall in this manner" (emphasis added).

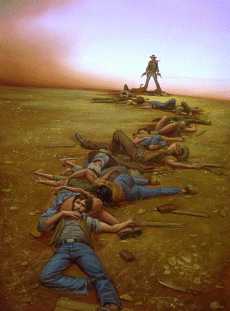

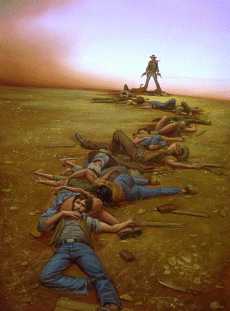

Cooper identifies a cardinal principle of the American knight-hero: the economy of violence. Natty believes all life is divinely created and must be preserved, especially that of innocent women and children: "life is sweet and not to be taken marcilessly [sic] by them that have white gifts." So even against armed enemies with violent intent, the true knight wounds rather than kills. In the Deerslayer, the young squire has yet to kill a man. Returning the fire of a hidden enemy, Natty mortally wounds him. Grieving, he holds the dying Indian, effectively reenacting the Pieta. The economy of violence became a staple of the American knights. In the early cowboy movies and television shows, the death count was reduced by the conceit of having guns shot from villains' hands. This trope turned "shoot-outs" into a kind of bloodless joust. But this moral restraint disappeared in the 1960s when a nihilistic realism replaced the Christian prohibition against taking innocent life.

In every novel, Natty is a righter of wrongs. While he sometimes rescues fair maidens, his great quest is to protect Americans as they journey into the lawless frontier. Cooper understood that a mobile, immigrant society of myriad sects and social conditions requires an everyman and outsider for its hero. Natty, an itinerant, orphan bachelor, fits the bill. The model of the democratic knight-errant, he is from no place, with no close relations other than his Mohican comrades in arms. More ideal than human, Natty lives as a holy hermit on the frontier, worshiping the Maker of all things. His perfect virtue makes Leather-Stocking the complete American Adam. Free from earthly sin, he serves his fellow democrats by protecting them from their fallen fellows in the Lord's Garden, i.e. the state of nature.

From there it was a short transition to the true cowboy hero:

Once the western frontier moved beyond the mountains, lakes, and forests, and crossed the Mississippi, a new vision of the democratic knight-hero was needed. Thus, the mounted rider arose to defend democracy on the open plains running to the Rockies. The first serious adaptation of knighthood to the cowboy/gunfighter, undertaken by Owen Wister in The Virginian (1902), was written after the frontier had closed. Hollywood made the cowboy hero universally popular. The new film industry was greatly aided by the dozens of novels, primarily by Zane Grey, available for movie development. Few films were easier to make than the early Westerns. Shot within a brief car ride from Los Angeles, they required few actors who could act, while filling the screen with the kind of action that movie audiences craved. Moreover, like most Arthurian tales, the characters' isolation on the broad plains created a totally melodramatic setting. No law limited the hero, or villain, in his acts of good and evil.

For more on the relationship between America's fictional and real cowboys, see America's Cultural Roots.

More on the god/cowboy connection

Another writer links gods and cowboys more directly and personally. From an essay titled "Heroes Are Here to Stay" in The Heroes (published 1968):

If you were walking toward the corner where you catch the school bus, and someone ten feet tall stepped out of the bushes, tapped you on the shoulder, and quietly called you by name, you'd know what it felt like to be a Greek Hero about to be "discovered."

Furthermore, if the tall individual said to you: "You're really the nephew of a king...but to prove it to your fellow classmates, you'll have to do several rather difficult things..." you'd probably swallow twice and listen respectfully.

What might you, as a potential Hero, be called upon to do? Since this is the Twentieth Century, not Ancient Greece, possibly something like the following: Run from New York to California...carry a skyscraper on your shoulders from Los Angeles to San Francisco...cut down a Redwood tree with a pocket knife...and read every book in the public library between noon and dinnertime on a Saturday afternoon!

You couldn't do it without help, of course, nor could the Heroes of Ancient Greece. How you—as a student—found help, and managed to overcome every obstacle, would make a fascinating story. That's one of the reasons why stories about Greek Heroes are so intriguing. They somehow managed to do what they were asked to do.

Overcoming obstacles isn't the only reason why heroes of the past and present set our imagination on fire. We're also drawn to them because they're courageous, and aren't afraid to accept challenges. They never hesitate to stand up for what they believe in. Since we'd all like to discover more of these qualities in ourselves, we find ourselves hero-worshipping heroes, partially because they seem slightly "larger than life."

Heroes Not a Greek Monopoly

Before taking a closer look at the mythology that produced Heroes with strange names like Perseus, Jason, Theseus, and Heracles, let's admit that the creation of heroes was definitely not a Greek monopoly. The Western world has continued to create Heroes ever since the Greeks, because people need them. Here's a short list of fairly recent historical figures who have become true Heroes in the Greek sense of the word, though perhaps not all of them have completely deserved the title:

Davy Crockett...Daniel Boone...Sam Houston...Stonewall Jackson...Napoleon...Richard the Lion-Hearted...Wild Bill Hickock...Buffalo Bill...Lawrence of Arabia...and a handful of "Ace" pilots from World War One.

Going back quite a bit further in history, we find that Cyrus the Great of Persia, Alexander the Great, Cleopatra, and the very talented Julius Caesar all became Hero-myths, even though they were flesh-and-blood people to begin with.

Are we still creating Hero-myths right now? Are we continuing to favor certain real-life person with heroic stature? Of course we are...and there's nothing wrong with that. Heroes give us something to try and measure up to. Great athletes in every field of sport tend to become true Heroes, because people look up to them. A few movie stars become heroes for the same reason. It's normal to wish we were like glamorous individuals who have traits we'd like to find in ourselves.

Greek Hero and Western Lawman

There may not seem to be much connection between a Greek Hero and the typical Western lawman as portrayed in movies and on TV, but there is. The lawman we insist on seeing on the screen is brave and resourceful. He's a figure with powerful appeal because he overcomes all obstacles with unflinching strength and dignity. We'd all like to be like that, just as the Greek man-in-the-street wished he were as sturdy and clever as Heracles.

Consider this: The lawman of Western films defends other people. His purpose in life is to combat Evil. He's strong and silent and never boasts. In the typical basic story, he rides into town alone, hitches his horse, walks into a local establishment, gets insulted by the villain and his henchmen, eventually has a victorious "showdown," and quietly rides out of town again.

This primary story is so popular that it's a world-wide favorite. That it's a deeply satisfying Hero-myth is proved by the fact that film-makers as far away as Germany and Japan turn out "Westerns" year after year! In short, the Old West Hero-myth is as deeply meaningful as any Greek Hero-myth, and will probably be around just as long.

Interesting that the feats suggested for a modern-day Greek Hero are things Superman or Flash could accomplish easily. That implies a connection to me. See the final sections of this analysis for more on the subject.

Greek myths and Western bias

"Heroes Are Here to Stay" concentrates on the ancient Greek myths—perhaps assuming the Biblical stories of the same millennium are historical "tales" or "accounts" rather than myths or legends. Actually, there's good evidence that Mark and the other apostles largely invented the story of Jesus. There's also good evidence that Mark based his narrative on the Greek epics. As a reviewer wrote about Dennis R. MacDonald's book The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark:

The thesis of this book is that Mark's account of Jesus contains so many parallels with, and allusions to, the Homeric epic of Odysseus that it is impossible to rule out direct influence. Mark is also indebted to the Iliad: It is not a matter of some comparison of one hero to the other on mere grounds of a general cultural convergence mediated by Old Testament traditions or by Judaeo-Hellenistic syncretism. An uninhibited literary and cultural analysis sees "flags" strategically placed by the literary artist Mark to call attention to parallels and differences between Jesus and Odysseus, Jesus and Hector. The plot, as it were, is the same in the Gospel account and the epics, since both Odysseus and Jesus set forth on a journey with flawed followers, suffer many things, and resist temptation; both Hector and Jesus approach death complaining their gods have abandoned them, and so on. There are also convincing verbal echoes of Homer in Mark, who, like other contemporary Greek writers, was brought up on Homer.

"Heroes Are Here to Stay" is a blatantly Western view of heroes, of course. Its heroes are basically warriors, even conquerors. (Cyrus the Great? Napoleon?!) There are no peacemakers as heroes—no diplomats or priests, healers or teachers. No Jesus, Buddha, or Dalai Lama; no Einstein, Gandhi, or Martin Luther King Jr. And no women, who embody feminine traits the West often disdains. No Joan of Arc, Elizabeth I, Catherine the Great, Madame Curie, Florence Nightengale, Susan B. Anthony, or Golda Meir.

In the Western worldview, a hero is someone who reaffirms the traditional view of right and wrong. He is not a radical or revolutionary who overthrows the existing order to establish a better one. That may explain why Jesus, Gandhi, and King don't make the standard list.

At least heroes from the Bible to the Revolutionary War contributed to Western civilization, whether their contemporaries realized it or not. How much less likely to make the honor roll are those who fought against the dominance of Western civilization: Tecumseh, Simon Bolivar, Sitting Bull, Pancho Villa, Geronimo, Kemal Ataturk, Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, Gamal Abdel-Nasser, Fidel Castro, Nelson Mandela. Legions of indigenous and Third World people have honored these leaders, but you won't find many statues of them in Euro-American galleries.

Would we really all like to be Hercules, John Wayne, or Superman? That seems like a white, male conceit to me. Billions of people would say working hard, finding love, and keeping the world going are more important than winning or losing battles.

Ask a typical woman if her goal is to be a "hero" who conquers enemies with superior strength or firepower. I'm guessing the answer will be no.

As for me, I'd "settle" for being the next Homer, Shakespeare, or Heinlein—someone who tells the stories about the heroes. After all, Hercules, Wayne, and Superman wouldn't be anywhere unless someone gave them substance, put them in motion, challenged them to perform heroic deeds. The hero is really a puppet; the storyteller is the one who inspires us.

Now let's see how the American pioneer, gunfighter, or lawman—the cowboy—relates to the modern hell-on-wheels (super)hero who shoots first and asks questions later.

*****

Cowboys and superheroes

If we define "cowboy" loosely as anyone who fights according to his (or her) own moral code using guns, we immediately see that the majority of American heroes over the last 200+ years are cowboys of one sort or another.

As the frontier closed, cowboys moved with other Americans to an urban environment. Engeman explains how the cowboy became a detective and then an astronaut:

Long before Hollywood captured the Western hero on film, a new "frontier" had opened in America. New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles appeared as strange and hostile to many Americans as had the shores of Massachusetts, the forests of upstate New York, and the Great Plains to their ancestors. Rural immigrants, like Theodore Dreiser's Sister Carrie (1900) were alienated from the "noir world" of the new urban frontier, filled with gin, drugs, prostitution, gambling, and crooked politicians and cops. Several decades elapsed before writers caught up to this new social reality. But by the time of the Depression and New Deal, this urban frontier began to be populated by democratic Christian knights. Raymond Chandler, the creator of the first truly heroic detective, Philip Marlowe, was born in America but educated in England. After returning to the United States, he failed in business only to recreate himself as a writer, publishing his first novel, The Big Sleep, in 1939. Philip Marlowe, originally named Philip Malory after Thomas Malory, incarnates yet another version of the American knight-errant. Chandler was influenced by T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land (1922), which had revived Arthurian themes. Chandler describes Marlowe in this way:

He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor—by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it…. If he is a man of honor in one thing, he is that in all things. He is a relatively poor man, or he would not be a detective at all. He is a common man or he would not go among common people. He is a man of character or he would not know his job. He will take no man's money dishonestly and no man's insolence without a due dispassionate revenge. He is a lonely man and his pride is that you will treat him as a proud man or be very sorry you ever saw him.

All of Marlowe's "jobs" become quests extending far beyond his appointed task. These quests end only when he has healed his client, and pulled from the fetid urban jungle the knowledge necessary to reward and punish. On the urban frontier, as in John Locke's state of nature, Marlowe is judge and executor of the laws of nature.

Others agree the detective, a modern-day cowboy, is also a modern-day knight:

The hard-boiled detective has been characterized as a white knight whose code of honour is his only armour against medieval dragons.

Mark Hagen, Dreams and Film Noir

The knight is the historic antecedent of the hard-boiled detective.

William Marling, The Big Sleep – Raymond Chandler (1939)

Finally, as Engeman explains, cowboy-knights headed into space:

The democratic knight is also found in America's mythic forays into space—the "final frontier"—in "Star Trek" and "Star Wars." Since space travel requires cooperative planning and regimented crews, space ships are more like naval vessels than they are the anomic settings of our solitary democratic heroes. Nevertheless, the officers of the USS (United Star Ship) Enterprise defend democratic justice and liberty for all citizens, human or not, in the United Federation. Like earlier heroes, they face an untamed wilderness (in this case, outer space) where prowl new enemies of democracy, the Klingons and Romulans.

"Star Wars" more closely fits the individualism and heroism of the democratic knight-errant, even though the Jedi are modeled on an established order of knights rather than the usually self-taught, self-sufficient American warriors.

The cowboy/astronaut linkage is common in our culture: in TV shows such as Star Trek (pitched as a Wagon Train to the stars) and in movies such as Space Cowboys and Toy Story (starring Woody and Buzz Lightyear).

Although Engeman doesn't discuss superheroes, the space-cowboy connections are clear. Some superheroes are literally astronauts or space travelers: the Fantastic Four, Captain Mar-Vell, Hawkman, Mon-El. Some are born while investigating other scientific frontiers: Peter Parker (Spider-Man), Barry Allen (Flash), Bruce Banner (Hulk), Ray Palmer (Atom), Hank Pym (Ant-Man/Yellowjacket), Alec Holland (Swamp Thing), et al.

Varieties of cowboys

From the earliest to the most recent gunslinger, cowboys fall into a few broad categories:

Real cowboys: The Minutemen, Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, George Armstrong Custer, Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickock, Annie Oakley, Jesse James, Wyatt Earp, Billy the Kid.

Early pulp-fiction cowboys: Natty "Hawkeye" Bumppo, Allan Quartermain, the Lone Ranger, the Cisco Kid, the Continental Op, the Shadow, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, Mike Hammer, various detectives.

20th-century cowboys: Teddy Roosevelt, Elliot Ness and the Untouchables, various G-Men, George Patton, Douglas MacArthur, the Green Berets, Barry Goldwater, Ronald Reagan, Daryl Gates and the LAPD, Bernie Goetz, various gun lovers and militia men.

21st-century cowboys: George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, various conservative pundits and talk-show hosts.

Early movie cowboys: William S. Hart, Tom Mix, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Gary Cooper, John Wayne, Alan Ladd/Shane, the Lone Ranger.

Modern movie cowboys: James Bond, Matt Helm, Shaft, James Coburn/Flint, Clint Eastwood/Dirty Harry, Charles Bronson/Death Wish, Sylvester Stallone/Rambo, Arnold Schwarzenegger/Terminator, Bruce Willis/Die Hard, Mel Gibson/Lethal Weapon, Indiana Jones, Brendan Fraser/The Mummy, Van Diesel (XXX).

Modern TV cowboys: The Lone Ranger, Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone, Marshal Dillon/Gunsmoke, Bat Masterson, Maverick, the Virginian, the Rifleman, the Cartwrights/Bonanza, Paladin/Have Gun Will Travel, Branded, Rawhide, Peter Gunn, Alias Smith and Jones, Wild Wild West, Secret Agent Man, I Spy, the Saint, the Green Hornet, the Avengers, Man from U.N.C.L.E., the FBI, Hawaii Five-O, Mannix, Kojak, Baretta, Starsky and Hutch, McCloud, Rockford, SWAT, Miami Vice, the A-Team, Magnum P.I., Buntz/Hill Street Blues, Sipowicz/NYPD, Chuck Norris/Walker.

Modern fictional cowboys: Various heroes from Louis L'Amour, Zane Grey, Max Brand, Larry McMurtry, Cormac McCarthy, et al.; Stephen King's Roland the Gunslinger.

Air and space cowboys: Captain Midnight, Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers, Tom Corbett, Captain Kirk, Han Solo, Captain Archer/Enterprise.

Comic-book cowboys (traditional): Solomon Kane, the Lone Ranger, the Two-Gun Kid, the Rawhide Kid, Kid Colt (and many other gunslingers), Jonah Hex, the Vigilante.

Comic-book cowboys (superhero): Nick Fury, Punisher, GI Joe, Vigilante, Grimjack, Scout, American Flagg, Jon Sable, Firearm, Deadshot, Guy Gardner: Warrior, Arsenal, Cable, Bishop, Deadpool, Martha Washington, Preacher, Hitman, Marv/Sin City, Danger Girl, Body Bags, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider.

The gunslinger as American

Note the recurrence, over and over, of real gunslingers like Daniel Boone and fictional gunslingers like the Lone Ranger. That and the continuing popularity of gunslingers such as John Wayne show how deeply Americans identify themselves with cowboys.

Note that, with very few exceptions, these cowboy heroes are all Anglo-Saxon men. In the American mind, Americans are the world's true heroes—the inheritors of traditions begun with Hercules, Jesus, the Christian knights, the Pilgrims, and the Founding Fathers. After 2,000 years, Michael Jordan is about the closest America has come to a cultural hero who doesn't fit the WASP pattern.

To Americans, the hero also has to be an American. Or a near-American like James Bond. Americans even remake Jesus into an Anglo-American, depicting him as a pop star and identifying him with patriotism.

Robert Harris, author of Enigma (a thriller about World War II code-breakers), noted this tendency. He ragged on the "sheer stupidity" of Hollywood film heroes in the British newspaper The Guardian (repeated in the LA Times, 8/23/01):

No matter what the situation or where the film is supposed to be set, an American has to be central, to be seen as the good guy or save the day in some way. It's a form of cultural imperialism.

If we expanded the cowboy idea to include any armed or armored warrior, the list of icons would be even longer: the Transformers, Luke Skywalker, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, TV's Hercules and Xena, the Power Rangers, and many others. Even Pokémon imitates the essential elements of cowboy myths: two lone warriors, face to face, drawing and firing their weapons. That the weapons are cute li'l animals rather than arms is a detail.

Besides cops, detectives, and secret agents, who helped take us from the traditional John Wayne cowboy to the postmodern Clint Eastwood cowboy? None other than that heroic proto-cowboy, Hercules, again. From the LA Times, 9/3/01:

Like the T-shirted Marlon Brando of "A Streetcar Named Desire," the Hercules film heroes represented a transition between the drawlin', gun-slingin' machismo of John Wayne and the semi-articulate, secretly sensitive anti-hero figure who emerged in the Italian spaghetti westerns such as "A Fistful of Dollars" and "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly."

For all their ludicrous feats and hyperbolic builds, the Hercules heroes were loners, outsiders, rugged individualists fighting against a corrupt system. They spoke to a sense of male alienation within the movies and postwar society at large.

So we've gone from the earliest gunslinging American pioneer—Natty Bummpo or the Minutemen—to the latest superheroish American gunslinger—Preacher or Lara Croft. To complete the circle, let's list the connections between modern superheroes and the original gods and heroes.

*****

Superheroes and gods

A glorius place, a glorious age, I tell you! A very Neon Renaissance—And the myths that actually touched you at that time—not Hercules, Orpheus, Ulysses and Aeneas—but Superman, Captain Marvel, Batman.

Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, 1968

Chapter 2: It Started with Gilgamesh: The History of the Superhero

Danny Fingeroth, Superman on the Couch : What Superheroes Really Tell Us About Ourselves and Our Society

"Superhero stories are the fairy tales of today and they require a lot of color and sense of fantasy," said comic-book giant Stan Lee in the LA Times, 8/28/01. In other words, superheroes fill the same role as the legendary heroes—the gods and demi-gods, warriors and knights, cowboys and cops—of yore.

The connections between gods and superheroes range from blatant to subtle. On the blatant side, we have gods and demi-gods who are superheroes: Thor, Hercules, the New Gods. Then there are those with clear mythological or legendary antecedents:

- Wonder Woman: Athena, Artemis.

- Captain Marvel: Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles, Mercury.

- Sub-Mariner, Aquaman: Poseidon/Neptune.

- Human Torch: Ra, Apollo.

- Flash: Hermes/Mercury.

- Hawkman: Horus, Icarus.

- The Spectre: Hades/Death.

- The Fantastic Four: The four elements (air, water, fire, earth).

- Hulk: Hercules, Atlas, Samson, Goliath.

- Spider-Man, Beast, Black Panther, Wolverine: Any half-man, half-animal creature (the Minotaur, centaurs, satyrs, et al.).

- Medusa, Gorgon, Triton: Medusa, Pan, Triton.

- The Teen Titans, Wonder Girl: The Titans.

- Zuras, Ikaris, Thena, Makkari, Sersi (Eternals): Zeus, Icarus, Athena, Mercury, Circe.

- Dr. Magnus (Metal Men), Forge: Hephaestus/Vulcan.

- Sandman: Morpheus.

- Cyclops: Cyclops.

- Atlas (Thunderbolts): Atlas.

- OMAC: Agamemnon, Ajax, any Greek or Trojan hero.

- Doc Samson: Samson.

- Giant-Man/Goliath: Goliath.

- Wasp, Yellowjacket, Ant-Man, Atom: Fairies, pixies, homunculi.

- Silver Surfer: Jesus Christ.

- Angel: Icarus, angels.

- Daredevil: the Devil.

- Green Lantern, Johnny Thunder: Aladdin and his lamp/genie.

- Dr. Fate, Dr. Strange, Starman: Merlin.

- Iron Man: armored knights.

- Shining Knight, Black Knight, Swordsman, Terminator the Deathstroke: Knights of the Round Table, Three Musketeers, Scarlet Pimpernel.

- Green Arrow, Hawkeye: Robin Hood, William Tell.

- Robotman, Metal Men, the Vision: Pygmalion, the Golem, Frankenstein's Monster.

As for the two greatest superheroes, we could say Superman is an amalgam of every great and powerful warrior: Zeus, Hercules, Achilles, et al. In other words, the archetypal sky-god. And Batman is an amalgam of every scary demon or bogeyman. In other words, the archetypal man-beast.

A couple of notes on these two heroes:

Superman

Moses is a good figure to compare to Superman. Remember baby Moses floating down the Nile in a basket? Think of baby Kal-El sent off through space in his rocket. Both of these events lead to heroes with two sets of parents, conveniently enough.

Bill Svitavsky, Web posting

[I]n presenting an otherworldly being, [Jerry] Siegel seems to have touched upon a mythic theme of universal significance. Superman recalled Moses, set adrift to become the people's savior, and also Jesus, sent from above to redeem the world. There are parallel stories in many cultures, but what is significant is that Siegel, working in the generally patronized medium of the comics, had created a secular American messiah.

Les Daniels, Superman: The Complete History

"Jesus was portrayed as a new Moses," writes Earl Doherty in The Jesus Puzzle, "with features which paralleled the stories of Moses." The Moses legend, in turn, derived from the Egyptian legend of the god Osiris. So the Superman archetype spans all of human civilization.

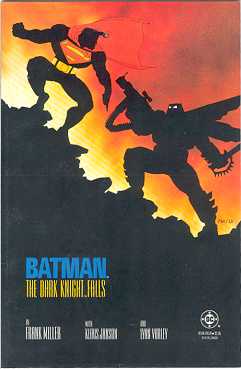

Batman

Another important archetype for understanding super-heroes is the Trickster. Tricksters tend to shape shift and/or wear disguises (like masks & capes), get caught in traps (like villains' deathtraps), and participate simultaneously in both human and animal natures (like Batman, Spider-Man, et al.). In Jungian psychology, tricksters are tied to the Shadow, so dark heroes are often particularly tricksterish.

Bill Svitavsky, Web posting

Is it coincidence Superman, Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, and Thor don't wear masks while Batman, Spider-Man, Daredevil, and Wolverine do? No. The bright, god-like heroes are open and aboveboard, while the dark, demon-like heroes are shrouded and mysterious.

The Trickster character is central to many indigenous tribes, and those tribes are as old as or older than so-called civilization. So the Batman legend also spans human civilization.

Science vs. mystery

Is it a coincidence superheroes are sometimes called "science heroes" or "mystery men"? No. One label refers to the heroes' superhuman, god-like qualities. The other refers to their supernatural, demon-like qualities. Superman is more the science hero, while Batman is more the mystery man.

Is it a coincidence there were more magical, supernatural heroes back in the '40s, when superheroes first developed? No. Before nuclear energy, computers, and space travel, comic-book creators were still feeling their way. Your mutant, techno-warrior, genetically-enhanced superheroes weren't conceivable then.

Even the color schemes reflect this point. Back when the Justice Society was America's team, red and green seemed the predominant hues. Robin, Green Lantern, Starman, Dr. Mid-Nite, Hawkman and Hawkgirl, Johnny Thunder, Mr. Terrific, Green Arrow and Speedy, Spy Smasher...and soon, Jor-El, Jimmy Olsen, the Martian Manhunter, Ultra Boy, and Colossal Boy.

Now that mutants and cyborgs rule the comic-book scene, blue and black are the trendiest shades. The last major superhero to be mainly green was...? So we've gone from heroes the color of blood and life to heroes the color of metal and death.

Is it a coincidence Hitler co-opted Nietzsche's Superman at the same time Siegel and Shuster created their Superman? No. Hitler's mad schemes were the epitome of science gone awry. The two Supermen represent the yin and yang of technological belief.

Even Superman's real name, Kal-El, resonates culturally. One famous "Calvin" in history is John Calvin, whose philosophy emphasized "the supremacy of the Scriptures in the revelation of truth, the omnipotence of God, the sinfulness of man, the salvation of the elect by God's grace alone, and a rigid moral code" (American Heritage Dictionary, New College Edition). Meanwhile, "El" is a Hebrew prefix meaning "strength."

Another famous Cal is Calvin Coolidge. "Silent Cal" came to prominence by breaking a police strike, campaigned with the slogan "Keep Cool and Keep Coolidge," and staunchly defended the status quo ("the business of America is business"). Many have noted how Kal-El also defends the status quo with a righteous moral code; we could call him a neo-Calvinist.

Even Cal Ripken Jr. the baseball player is known as a quiet traditionalist with a steadfast approach to the job. These qualities helped him set the record for most games played in a row.

Referring to this essay's prologue, is it a coincidence Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, and the X-Men (all science-based heroes) have become the biggest comic-book icons in the public mind? And that Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, Green Lantern, and Thor (all fantasy-based heroes) have always been second-stringers of a sort, unable to break through as pop icons? Again, no. America is the ultimate technological culture, and science-based heroes are the ultimate expression of that culture.

Two thousand years ago, a hero granted powers by the gods (Captain Marvel) would've resonated more than a hero rocketed from an advanced world (Superman). Today, it's the other way around. The Man of Steel (aka the Man of Tomorrow) is the Big (Blue) Cheese; the Big Red Cheese is yesterday's news.

*****

The point, finally

Who we write about is far from arbitrary. Rather, it reflects the deepest, most significant trends of history. Our choice of hero literally tells us where we've been and where we're going.

Let's grossly oversimplify world history and look at who our heroes have been. Note the following reflects the dominant Western/European/American view of history, not the reality:

- The creation of civilization. The law-givers and philosopher kings. Moses, David, Jesus; Plato, Socrates, Aristotle.

- The spread of civilization throughout the "known world." The warrior kings. Alexander the Great. Julius Caesar and the Roman legions. Charlemagne and the knights in shining armor.

- The spread of civilization across the Atlantic. Explorers such as Leif Ericsson, Columbus, and Magellan. Pioneers such as the Spaniards (in New Spain), the Pilgrims, and the Colonials. Civilizers such as Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Teddy Roosevelt.

- The spread of civilization around the globe. America as the world's source material (Walt Disney, John Wayne, Michael Jordan). America as the world's shining beacon (American GIs, JFK and Camelot, the astronauts). America as the world's superpower (Reagan, Bush, Powell).

The line that began with Moses and the first gathering of the "chosen people" has ended with America atop the world's heap. Our righteous country stands for truth, justice, and the American way and so does our righteous superhero. An archetypal character like Superman is the embodiment and culmination of human history.

Attentive readers will note that this conclusion neglects the 85% of the world that isn't Euro-American. Precisely. Though some people would wish otherwise, history has yet to end. The next challenge in our historical development will be perhaps the trickiest.

Unless large-scale space travel becomes a reality, we have nowhere left to spread. The dissemination phase of civilization is over. The next challenge is integration: meshing the dominant Euro-American culture with the non-dominant but much larger and older non-Euro-American cultures.

We can keep going in a straight line: "taming" and developing and building the world until it's one paved-over shopping mall and parking lot. As the last fish is caught, the last tree is cut, the last well runs dry, we can watch the great American civilization collapse into rubble. As Ozymandias put it, "Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Or we can turn in a new direction: blending America's can-do drive and technology with the rest of the world's cultural norms. Living within our means. Valuing community over competition. Thinking seven generations ahead.

The choice is between seeing the present world go up in smoke or evolve into a kinder, gentler place. If we want the latter, we need a new kind of leader and icon. We need a new heroic paradigm.

Superman's brawny, know-it-all attitude won't cut it here. Brute force was fine for beating the Indians and digging the Panama Canal, but now we're dealing with bioengineering and nanotechnology. We need the subtlety and cleverness of a Trickster to merge the old and the new.

The next generation

Just as Superman was the ultimate hero of the past, a new breed of hero will lead us forward. These paragons will combine the best of Western intellect and indigenous soul (and vice versa). In short, they'll be much like Peace Party, the multicultural heroes of the third millennium.

Why write about (super)heroes? Because each hero—Greek god, knight in shining armor, gunslinger, superhero—defines an epoch of civilization. Someone, somewhere, is creating the myths that will define the next epoch—when we choose to live in harmony, or die.

Who knows? Maybe it's the next ultra-violent music, game, or movie product. Or maybe it's right here.

Rob

Related links

Why write about Native Americans?

The 200 greatest pop culture icons

Culture and Comics Need Multicultural Perspective 2000

Why write fiction: the power of storytelling

America's cultural mindset

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.