KEYNOTE SPEECH

KEYNOTE SPEECHSYMPOSIUM ON AMERICAN INDIAN ISSUES IN THE CALIFORNIA PRESS

FEBRUARY 21, 2003

University of California at Los Angeles

KEYNOTE SPEECH

KEYNOTE SPEECH

SYMPOSIUM ON AMERICAN INDIAN ISSUES IN THE CALIFORNIA PRESS

FEBRUARY 21, 2003

University of California at Los Angeles

By Mary Ann Weston, Associate Professor

Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University

There's a danger in being the cleanup hitter at an event like this: Everything worth saying may have been said. But I won't let that deter me.

I hope in these final remarks to tie together and, perhaps, put in context some of the ideas and feelings we've heard today. As a journalist by vocation who has centered my academic research around coverage of Native people in the mainstream news media, I applaud the sponsors for calling this meeting to discuss building respectful, productive relationships among the tribes, the media and policy makers. This is highly important, tough work.

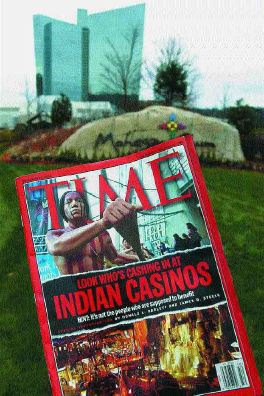

When I attended a similar conference last fall at Harvard, I mentioned that the new relationships between New England tribes and their communities—forged through tribal gambling operations—was a huge, under-covered national story. No longer. Now we can thank Time magazine for putting tribal gambling on the national agenda. But in ways, I suspect, not quite satisfactory to the tribes. If you haven't seen them, the stories are in the Dec. 8 and 15 issues of Time. There's also a spirited response by Lincoln Journal-Star columnist Jodi Rave Lee at about that time. I would like to use those Time magazine stories as a departure point to discuss relationships between Indians and the news media.

From my research in journalism going back to the 1920s I believe the news media have—with a few outstanding exceptions—not told Native Americans' stories well. Native people, their lives and causes, have been ignored, distorted, stereotyped and trivialized. I also believe news people, many of whom are my colleagues and former students, are usually well-intentioned and try to get it right. But, as the stories in Time exemplify, even the best, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists can miss by a mile.

Why do we see such journalism in such a respected publication? I'd like to take a stab at an explanation. There are two things going on: The burden of history and the clash of cultures.

In the time and place of my childhood "cowboy and Indian" movies and television programs were an unquestioned part of growing up. In Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts children learned Indian "lore" and "crafts" and "dances." Much of which, it turns out, were pretty bogus. The overwhelming effect of these popular culture images was to impart stereotypical attitudes about Indians. These usually aren't conscious thoughts, but unconscious mindsets that inform the ways people think—and journalists approach stories.

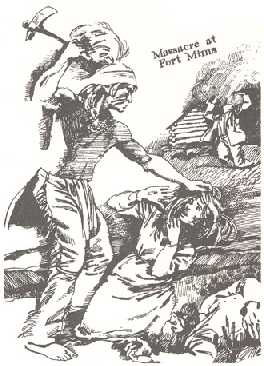

Those attitudes and mindsets didn't start with cowboy and Indian movies. They go back to the 16th and 17th centuries when Europeans were trying to make sense of the peoples they found in the "new" world. Somehow, they had to fit these folks into worldviews and mindsets that made no provision for them.

The result was imagery that projected European fears of the "savagery" they imagined in the absence of civilization and the nobility of an, also-imagined, pristine state of nature. These images, the stuff of myth and fiction, have been repeated so often and in so many settings that they have taken on an aura of fact. I'm sure you know them well.

There is the "good Indian." This image often takes the form of the "noble savage" who has an innate closeness to and communion with nature, who is at home in the natural world. Think, for example, of the image of the Indian maiden on a container of Land o' Lakes butter.

The flip side of the "good Indian" is the "bad Indian," an image that takes many forms. Historically, "bad Indians" were "savages." They were assigned qualities that embodied everything colonists and later settlers feared becoming or succumbing to in the vast, alien wilderness: paganism, lechery, brutality, cruelty, indolence, treachery and so on.

Later, after Native Americans ceased to be a military threat, a related image, the "degraded" Indian, appeared. This image depicted someone who was an object of derision or pity, someone who couldn't cope with the complexities of white civilization. He was, in the words of author Vine Deloria, someone with a "plight."

He might be an alcohol abuser or someone who couldn't manage sudden wealth—from oil royalties in Oklahoma in the 1920s—or casinos today.

Clearly such images told us more about Euro-Americans than about Native peoples themselves. And the fact that the images are still around after more than 500 years may also tell us something about whites. Because constructing such views of the "other" is an exercise in power. Defining the "other" in negative terms gives the dominant party greater control over the discourse. As Assemblyperson Jackie Goldberg pointed out earlier, the uses of these stereotypes can powerfully influence public policy.

What has this to do with stories in Time magazine or elsewhere in the mainstream press? I submit that these perceptions are virtually hard wired into the DNA of everyone who grew up in the United States. It is the burden of our history.

The Time series adopts an unrelentingly negative tone that implies that activities acceptable to whites—lobbying lawmakers, accumulating wealth, having outside investors—are questionable when done by Indians. Nowhere in the series could I find a coherent explanation of the historic underpinnings of tribal sovereignty.

I'm also wondering if there might not be some unconscious assumptions—i.e., stereotypes—at work here: assumptions that Indians aren't worthy of or able to handle sudden wealth; that Indians are not supposed to be rich; that Indians supposed to be poor supplicants at the seats of power, not players with clout. It's almost as though Native people are punished for not conforming to the stereotype of the poor, degraded Indian.

This is not to say Indian gaming should not be investigated. Or that flaws—whether with the tribes or the federal government—shouldn't be pointed out. But the investigation and the tone of the resulting stories should be even-handed.

Journalism, ideally, gives its audience facts and reality—the news "without fear or favor." Yet as we have seen, it is possible for flawed images to appear in the news.

Why is this? How does journalism's often-invoked commitment to factuality and fairness result in inaccurate portrayals?

Clearly the mindsets and cultural assumptions of journalists play a part. But also there is a clash of cultures here. As Chet Barfield and others have pointed out, journalists live in the world of the here and now, a world of hard facts and rigid deadlines, a world of irony and skepticism. But also a world of curiosity and lifelong learning. Tribal cultures, on the other hand, may put higher value on listening, on conversation, cooperation, closeness of relationships, respectful attitudes, the importance of tradition and history.

We don't—and don't want to—change the core of either culture. But we do need mutual understanding. Let me try to address the culture of mainstream journalism, summarizing many points made earlier.

I submit that certain practices and traditions of mainstream journalism encourage the perpetuation of false stereotypes. You could put it this way: It's not intentional; it's institutional. It's not a conspiracy; it's the culture. What is it in this culture of journalism that leads to depictions that are at odds with its highest aspirations?

Here's one answer: Journalism tries to make sense of the world. That is, it seeks to take the randomness of events and transform them into stories—narratives that allow us to understand what is happening. Numerous scholarly studies have examined the role of myth and imagery in the news. Journalists sometimes dislike these studies. They say their stories just record what happened, letting the facts speak for themselves. They deny that they intentionally set out to construct myths or pass on inaccurate images.

And they're right. Often as not, some of the traditional practices of journalism are to blame. You heard about many of them this morning.

1) The perceived need for timeliness and speed, spurred now by the internet and real-time television reporting, gives journalists no time to reflect, seek background information, or more sources.

2) The traditional news values that favor conflict and violence over cooperation spotlight negative behavior—and negative images.

3) The need for brevity to accommodate the audience's short attention span makes it hard to construct nuanced portrayals of little-known groups.

4) The emphasis on the bizarre and the visually arresting highlights those with loud voices, extreme views and strange appearances rather than the thoughtful moderates.

5) The practice of valuing events over trends or situations tends to downplay complex issues such as sovereignty or treaty rights.

These practices themselves are culture-neutral. But they can work against giving audiences an accurate picture of Native peoples. And when you consider that many people's only acquaintance with Native Americans is through popular culture or the press, the importance of accurate journalism is clear. The journalists on this morning's panel who were praised are often, I suspect, working against these conventions to get perceptive, nuanced stories in their publications.

With such constraints, what can journalism do? Here are some suggestions, again, summarized from this morning's panels:

1) Context. Journalistic tradition dictates that stories focus on the newest, up-to-the-second latest development. But they should also make room for context—the historical and cultural circumstances that led up to the event. Today's stories of sovereignty and federal recognition fairly beg for such context.

Over and over I heard it said that the issue is complicated. Sovereignty is complicated. Tribal terminology is complicated. With respect, I must ask: More complicated than Iraq? More complicated than the Israel-Palestinian conflict? More complicated than learning why the space shuttle disintegrated? Journalists are smart people. Tribal leaders are smart people. Let's not sell each other short. The issues are not beyond human understanding and we should start from that positive premise.

2) News judgment. What makes a story a story? How often are Native American people used as sources on stories about fashion, health care, or the debate over war with Iraq? Certainly Indians have lives beyond casino controversies that might be depicted in the press.

3) Framing. Journalism is really a selection game. It's about what you leave in or take out; who you quote and who you don't; which people and places you describe and how; which e-mails or phone calls you make and which are returned; what goes in the lede and what's at the end of the story. Each of these choices—and more—powerfully shapes the story and the images it conveys. So journalists might ask themselves: Have they contacted both sides—or all sides? Have they rounded up the usual suspects or looked for leaders and followers? Have they written quotes or taped scenes that are the most bizarre or the most representative of the story?

For tribal leaders I can only reiterate and emphasize the advice given earlier.

In the years since I wrote Native Americans in the News I'm seeing some changes in journalism that affect both journalists and Native people. Journalism is less a mass communications medium and increasingly a niche-driven one. Its audience is fragmenting into many niche audiences as the population becomes more diverse. But ownership is more concentrated—fewer organizations control much of the media. It is important to reach your own audience, but it is also important to reach local and national media where public policy is made.

Also, journalism's declarations of the value of diversity are increasingly reflected in coverage. Reporters and editors of color, while still not represented in sufficient numbers, are prominent in many newsrooms. Though as a journalism educator, I don't see nearly enough Native students in my classes.

Finally and importantly, the power relationship between Native Americans and those who cover them is shifting. In earlier decades Native people had virtually no voice in the press. They were at the mercy of the images whites constructed. By the 1980s and 1990s, my studies indicated, Native people were "talking back to the media." They were insisting that their narrative, their version of events, be noticed. And, they were acquiring the political and economic power to make people listen. The press was asking them questions, listening to their answers and playing the stories prominently.

I believe we are at a watershed in relations between Native Americans and the media. Once the press ignored Native people. Now, for better or worse, Native people are newsworthy. They cannot be ignored.

All this, I hope, is moving us toward greater mutual understanding. And, moving us toward journalism—a story—shaped not by one powerful group's assumptions and images of a minority, but a narrative shaped by the interaction of equals.

Thank you.

Mary Ann Weston is author of Native Americans in the News: Images of Indians in the Twentieth Century Press. A description:

From the Pueblo land protests of the 1920s to the sports teams' mascot controversies of the 1990s, this book chronicles the depictions of Native Americans in the press. Weston shows how some images of Indians that date from the time of Columbus have persisted into the present, and she asks whether journalistic practices have helped or hindered accurate portrayals of Native Americans. Few books of this kind have given attention to both local and national press, or have dealt so extensively with the 20th century. Weston has incorporated a wealth of well-chosen examples, presenting an accessible account of this fascinating subject.

Related links

Native journalism: to tell the truth

Savage Indians

Good-for-nothing Indians

Greedy Indians

Stereotype of the Month contest

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.