Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

The "Vanishing Breed"

Representing Indians in the tragic mode is nothing new think "Last of the Mohicans" or "Dances with Wolves" because the "Vanishing Indian" was never meant to have a future in the first place. This is how culture has always supported colonialism.

To the extent that Natives are perceived as perched on the brink of extinction, settlers can feel secure in their knowledge that this really was an "empty continent," thus justifying their presence on it. Purging one's emotions over the awful effects of colonization is part of the process of justification hence, the persistent proliferation of tragic narratives.

Scott Lyons, "Leech Lake Storytelling Was Poor Journalism," Minneapolis Star Tribune, 6/5/04

*****

America's Manifest Destiny

In the 19th century, Americans began feeling confident in their ability to settle and rule the continent:

...[T]he fulfillment of our manifest destiny [is] to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.

John L. O' Sullivan, The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, 1845

Only problem was, the continent was already inhabited. To justify their depredations against the Indians, Americans conceived of a self-justifying rationalization. Doomed to defeat by their inferiority, they claimed, Indians were destined to vanish off the face of the earth.

As a book review in the LA Times, 12/26/04, explains:

Since their arrival on this continent, Euro-Americans have searched for ways to understand the native inhabitants whose lands they appropriated and cultures they often denigrated. Even while engaging in brutal military conflicts with Indian tribes, 19th century Americans devoured the Leatherstocking tales of James Fenimore Cooper, wept over sentimental Indian novels and plays, flocked to see Wild West shows and populated anthropology displays at world's fairs and museums. In literature, art, popular culture and science, Americans told stories about Indians to satisfy their own longings for adventure and rewrite an uncomfortable history.

.

.

.

As Euro-Americans searched for a framework through which to understand the native inhabitants of the continent, they imposed their own paradigms "noble" and "savage," for example on the cultures they encountered. Scientists tried to develop classification systems that would place Indians into groups defined by language or physical appearance; religious thinkers tried to determine whether the Indian peoples could be the remnants of the 10 lost tribes of Israel or the descendants of Noah's son Ham. Historians wondered whether the apparent "savagery" of the natives represented the degeneration of a once-civilized people, confirming a cyclical view of history, or an early stage in their development, supporting a progressive historical model. And through all the discussions ran the ominous thread of racialized thinking, the assumption that the native peoples were inferior to the Europeans, and the dominant metaphor of "the vanishing race."

At least the "savages" could choose the method of their demise. They could become "civilized" and disappear into America's "melting pot," eliminating themselves by assimilating. Or they could resist and be eradicated by the tidal wave of "progress" (led by the US Army).

Some choice.

Why vanish the Indians?

The book review suggests why Americans were so intent on assimilating (i.e., vanishing) the Indians. It delves into the psychology of glorifying the dream (the noble Indian) while denigrating the alleged reality (the savage Indian).

The book examines a variety of ways in which Indian characters were "staged," or represented, in literature, photography and performance and places this effort in an illuminating historical context: the rising tide of anxiety about national identity that accompanied the flood of immigrants at the turn of the 20th century and the refiguring of "American identity" that resulted. Trachtenberg shows how the fear of immigrant aliens expressed in politics and literature led to the reinvention of Indians as "first Americans" whose "disappearance" in the face of Anglo-Saxon power comforted those who feared America's increasing diversity. From congressional committee reports to citizenship pageants staged by Wanamaker's department store, Trachtenberg uncovers fresh material to shed new light on the role of Indians in America's imaginative life.

The starting point for this story is the famous narrative poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, "The Song of Hiawatha." Published in 1855, the same year as Walt Whitman's path-breaking "Leaves of Grass," "Hiawatha" created a faux epic, inspired by Finnish poetry that Longfellow read in translation. For Indian lore, Longfellow relied on the research of Henry Schoolcraft, a geologist who married an Ojibway woman and transmuted her accounts of traditional tales into folkloric fantasies.

In his eagerness to create an Indian epic that glorified a folk hero but concluded that Indians must give way to white "progress," Longfellow transposed the name of an Iroquois historical figure onto a collection of Ojibway myths. No wonder Emerson described the popular poem as "wholesome," for, as Trachtenberg comments, Longfellow succeeded in creating a generic "Indian" who quietly faded away with the approach of "the white-man's foot" at the poem's end.

Another book review comes to similar conclusions about Trachtenberg's book. From "What It Means To Be An Indian In America" in the Hartford Courant, 1/9/05:

Using the wildly popular 19th-century poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, "Song of Hiawatha," as a vehicle, Trachtenberg writes how the image of the fading, noble Indian was part of a long process of refashioning history. This featured a "remaking of alien natives into model Americans" who then became "models for those immigrant aliens." At the turn of the century in ascendant America, these new arrivals with their strange languages and cultures seemed far more menacing than the long-conquered native inhabitants of the continent.

Trachtenberg recounts essential history still often forgotten: how the concept of "manifest destiny" rose like a giant, crushing tide across Indian societies. Later, with the frontier vanquished and Ellis Island teeming with immigrants, the Indian, he writes, became "a source of national virtue and strength." This phenomenon was best personified in the early 20th century by the "Wanamaker Indian" -- a portrait of a dying, vanishing race craftily celebrated for profit by a chain of department stores.

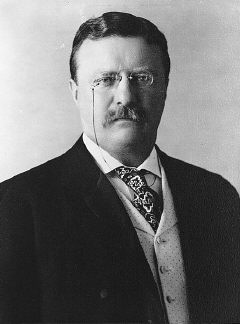

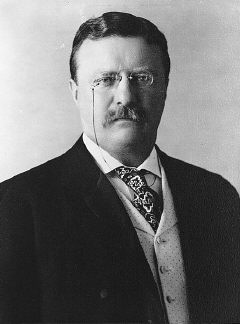

"Indians had been slaughtered; for the sake of the new race of Americans, they must be resurrected and commemorated, their 'pure' image preserved in gold," Trachtenberg writes. His book moves from Longfellow to President Theodore Roosevelt to the bizarre early 20th-century "expeditions" into Indian Country financed by the Wanamaker family, founders of the famous Philadelphia store.

Put more bluntly, it was a philosophy of "kill the Indian to save the man;" one that removed native children from families, took tribal lands for white settlers' use and suggested that only pure-bloods were "real" Indians.

Trachtenberg will hardly be embraced by those in the "that was then, this is centuries later" camp. His insightful and carefully researched analysis suggests that the myth of the long-disappeared native is essential to our view of what is American -- and what is Indian -- even if it doesn't necessarily match reality.

"Freezing the Indian image as 'pure' so that it could be incorporated as an ingredient in American whiteness was a cure to both blackness and the 'inferior' strains from Eastern and Southern Europe," he writes, discussing pictures by legendary photographer Edward Curtis.

In his unique and highly opinionated analysis, Trachtenberg links the transformation of the warrior to noble native with the 19th-century arrival of "hordes of Italian Catholics, Orthodox Slavs and Jews ...inundating cities, factories and mines, schools and public places all over America.

"The fundamental shift in representations of Indians, from 'savage' foe to 'first American' and ancestor to the nation, was conditioned by the perceived crisis in national identity triggered by the 'new' immigrants."

Both Indians and immigrants, Trachtenberg believes, were "entangled figures" who "were subjected to a process called 'Americanization'" -- an assimilation that could only be achieved, as Theodore Roosevelt observed, by "smashing the tribal mass."

"When dealing with Indians," Roosevelt told Congress in 1902, "our aim should be their ultimate absorption into the body of our people.'

Incidentally, this process of vanishing the Indians (i.e., glorifying the dream while denigrating the reality) continues today. We can see it in the actions of Indian wannabes and New Agers, and of devotees of Indian mascots, military terminology, and romantic characters such as Karl May's Winnetou.

It's similar to our attitude toward gays, another marginalized group. Love the sinner (the brave Indian warrior), hate the sin (his rejection of America's credo of greed and selfishness).

For more on America's historic attitude toward the "vanishing breed," see the following quotes.

The situation today

Many people think the efforts to eliminate the Indians succeeded. An article describes what it's like to be "vanished" in the 21st century:

From the Chicago Sun-Times:

Sorry for not being a stereotype

April 24, 2004

BY RITA PYRILLIS

How many of you would know an American Indian if you saw one? My guess is not many. Certainly not the bank teller who called security when an Indian woman a visiting scholar tried to cash a check with a tribal identification card. When asked what the problem was, the teller replied: "It must be a scam. Everyone knows real Indians are extinct."

And not the woman who cut in front of me at the grocery checkout a few months ago. When I confronted her, she gave me the once over and said: "Why don't you people just go back to your own country."

OK, lady, after you, I said, when I thought of it the next morning.

Even though I was born and raised in Chicago, strangers sometimes assume I'm a foreigner. For the record, I'm Native American, or Indian take your pick. I prefer Lakota.

Sometimes strangers think I'm from another time. They wonder if I live in a teepee or make my own buckskin clothes or have ever hunted buffalo. They are surprised when I tell them that most Indians live in cities, in houses, and some of us shop at the Gap. I've never hunted a buffalo, although I almost hit a cow once while driving through South Dakota.

Sometimes, people simply don't believe I'm Indian. "You don't look Indian," a woman told me once. She seemed disappointed. I asked her what an Indian is supposed to look like. "You know. Long black hair, braids, feathers, beads."

Apparently, as Indians go, I'm a flop, an embarrassment to my racial stereotype. My hair is shoulder-length, and I don't feather it, unless you count my unfortunate Farrah Fawcett period in junior high.

When you say you're Indian, you better look the part or be prepared to defend yourself. Those are fighting words. When my husband tells people he's German, do they expect him to wear lederhosen and a Tyrolean hat? Of course not. But such are the risks when you dare to be Indian. You don't tug on Superman's cape, and you don't mess around with a man's stereotype.

Native American scholar Vine Deloria wrote that of all the problems facing Indian people, the most pressing one is our transparency. Never mind the staggering suicide rate among Native youth, or the fact that Indians are the victims of violent crimes at more than twice the rate of all U.S. residents our very existence seems to be in question.

"Because people can see right through us, it becomes impossible to tell truth from fiction or fact from mythology," he wrote. "The American public feels most comfortable with the mythical Indians of stereotype-land who were always THERE."

Sure. Stereotypes don't have feelings, or children who deserve to grow up with images that reflect who they are not perfect images, but realistic ones. While Little Black Sambo and the Frito Bandito have gone the way of minstrel shows, Indians are still battling a red-faced, big-nosed Chief Wahoo and other stereotypes. No wonder people are confused about who Indians really are. When we're not hawking sticks of butter, or beer or chewing tobacco, we're scalping settlers. When we're not passed out drunk, we're living large off casinos. When we're not gyrating in Pocahoochie outfits at the Grammy Awards, we're leaping through the air at football games, represented by a white man in red face. One era's minstrel show is another's halftime entertainment. It's enough to make Tonto speak in multiple syllables.

And it's enough to make hard-working, decent Indian folks faced with more urgent problems take to the streets in protest. Personally, I'd rather take in my son's Little League game, but as long as other people insist on telling me when to be honored or offended, or how I should look or talk or dance, I will keep telling them otherwise. To do nothing would be less than honorable.

Rita Pyrillis is a free-lance journalist and a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe.

More examples of the "vanished breed"

I have been asked by school children if I still live in a TiPi, and I have been told by a young school aged child that I can't possibly be an Indian, because Indians were all killed a long time ago, and that's why the school mascot is an "Indian"so Indians can be remembered.

Mike Wicks, MASCOTS -- Racism in Schools by State

More on the "vanishing breed"

Are Indians vanishing again?

The mythology of the vanishing Indian

Related links

Natives sing it their way

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.