Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

America the Warrior Society

(9/27/04)

The American ideal, then, of sexuality appears to be rooted in the American ideal of masculinity. This ideal has created cowboys and Indians, good guys and bad guys, punks and studs, tough guys and softies, butch and faggot, black and white. It is an ideal so paralytically infantile that it is virtually forbidden — as an unpatriotic act — that the American boy evolve into the complexity of manhood.

James Baldwin, "Here Be Dragons," 1985

*****

Is violence universal?

The violence of our society is rooted in our masculine culture. We're No. 1, we proclaim—the best, the mightiest, the proudest. Our national goal is to win, beat the "others," be the last man standing.

But some say masculinity, competition, and violence are nothing but human nature. Is that true? Is "might makes right," "kill or be killed," "survival of the fittest" a general human attitude? Or is it an attitude specific to Western and American civilization?

A masterful analysis of US history suggests the latter:

Violence is the American Way

By Ira Leonard, AlterNet. Posted April 22, 2003.

Contrary to the mythical self-image of the United States as a peaceloving nation, war has always been an integral part of American patriotism.

"Increasingly, Americans are a people without history, with only memory, which means a people poorly prepared for what is inevitable about life — tragedy, sadness, moral ambiguity — and therefore a people reluctant to engage difficult ethical issues."

— Elliot Gorn, "Professing History: Distinguishing Between Memory and Past," Chronicle of Higher Education (April 28, 2000).

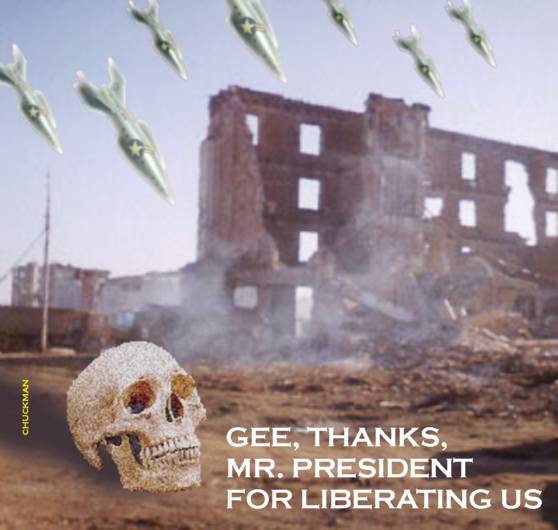

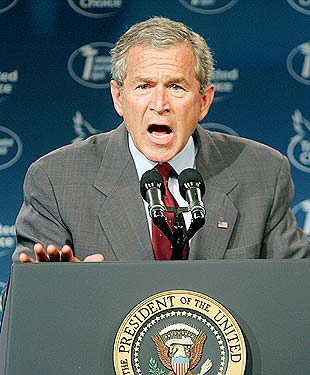

In August 2002, President George Bush began to drum up a war fever in America with a view to toppling Iraqi Dictator Saddam Hussein, alleged to be the possessor of weapons of mass destruction. Bush did so without providing the evidence, the costs, the "why now" explanation, or long-term implications of such a war.

And by October 2002, The United States Congress not only granted the president a virtual declaration of war for an historically unprecedented "pre-emptive war," but did so without raising any questions about the whys, the evidence, the costs, or long term implications for the nation — and for the world — of such an unprovoked invasion.

Only a democratic society accustomed to war — and predisposed to the use of war and violence — would accept war so quickly, without asking any questions or demanding any answers from its leaders about the war.

And only the opposition of the French, Germans, Russians, and Chinese finally forced some Americans to raise questions about what was actually being planned. This, coupled with the anti-war demonstrations on February 15th, 2003 by millions of people in 350 cities around the globe, delayed President Bush from actually launching this war against Iraq by mid-February 2003.

Nothing, however, seemed to stop the Bush administration's drive for war. Nor did the failure of American diplomatic efforts to get authorization from the United Nations' security council seem to bother the members of the Congress, virtually all of whom remained silent or in support of war. The incessant polls showed that a majority of the american population continued to support a preemptive war even as — or perhaps because of — increasingly angry objections were voiced by important longterm allies and antiwar demonstrators all over the world.

The reality untaught in American schools and textbooks is that war — whether on a large or small scale — and domestic violence have been pervasive in American life and culture from this country's earliest days almost 400 years ago. Violence, in varying forms, according to the leading historian of the subject, Richard Maxwell Brown, "has accompanied virtually every stage and aspect of our national experience," and is "part of our unacknowledged (underground) value structure." Indeed, "repeated episodes of violence going far back into our colonial past, have imprinted upon our citizens a propensity to violence."

Thus, America demonstrated a national predilection for war and domestic violence long before the 9/11 attacks, but its leaders and intellectuals through most of the last century cultivated the national self-image, a myth, of America as a moral, "peace-loving" nation which the American population seems unquestioningly to have embraced.

Despite the national, peace-loving self-image, American patriotism has usually been expressed in military and even militaristic terms. No less than seven presidents owed their election chiefly to their military careers (George Washington, 1789, Andrew Jackson, 1828, William Henry Harrison, 1840, Zachary Taylor, 1848, Ulysses S. Grant, 1868, Theodore Roosevelt, 1898, and Dwight David Eisenhower, 1952) while others, Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy, for example, capitalized upon their military records to become presidents, and countless others at both federal and state levels made a great deal of their war or military records.

Starting with President Woodrow Wilson early in the 20th century, national leaders began to use moralistic rhetoric when they took the nation to war. They assured Americans that the nation's singular mission in the world required the nation to go to war, but that when it went to war, America only did what was morally right.

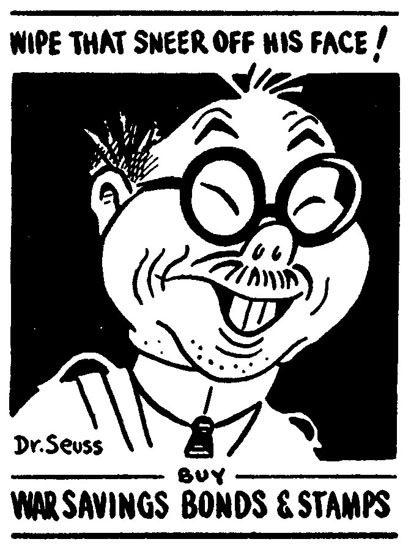

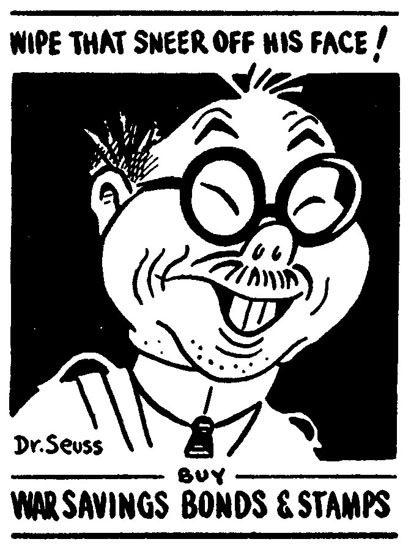

Secretary of State John Hay, in 1898, lauded the Spanish-American War as a "splendid little war." Commentators have touted World War II as the good war and those who fought in it, "The Best American Generation," and President George Bush, as he was about to launch a war against Iraq on January 29, 1991, asserted: "We are Americans; we have a unique responsibility to do the hard work of freedom. And when we do, freedom works."

This is not to suggest that all American wars have been fought for base motives, cloaked by self-serving moralistic rhetoric, but rather that Americans have little genuine understanding of the major role played by war throughout the American experience.

Historians, however, are well aware that war taught Americans how to fight, helped unite the diverse American population, and helped stimulate the national economy, among other significant things. But this is not the message that they have presented to the American people, concerned perhaps they might undermine Americans' self-image.

Just how frequent war has been, and how central wars have been to the evolution of the United States, only becomes clear when you start to make a list.

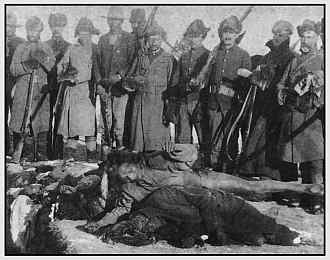

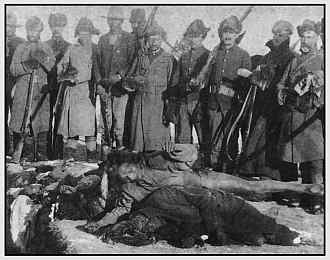

American wars begin with the first Indian attack in 1622 in Jamestown, Virginia, followed by the Pequot War in New England in 1635-36, and King Philips' War, in 1675-76, which resulted in the destruction of almost half the towns in Massachusetts. Other wars and skirmishes with Native American Indians would follow until 1900.

There were four major imperial wars between 1689 and 1763 involving England and its North American colonies and the French (and their Native American Indian allies), Spanish, and Dutch empires. During roughly the same years, 1641 to 1759, there were 18 settler outbreaks, five rising to the level of major insurrections (such as Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia, 1676-1677, Leisler's Rebellion in New York, 1689-1692, and Coode's Rebellion in Maryland, 1689-1692), and 40 riots.

Americans gained their independence from England and boundaries out to the Mississippi River, as a consequence of the Revolutionary War.

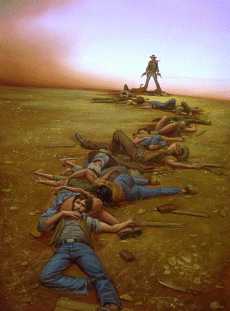

The second war against England, 1812-1815, reinforced our independence, while 40 wars with the Native American Indians between the 1622 and 1900 resulted in millions upon millions of acres of land being added to the national domain.

In 1848, the entire southwest, including California, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Utah and Wyoming, was obtained through war with Mexico. The Civil War between 1861 and 1865 was simply the bloodiest war in American history.

America's overseas empire began with the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection (1898-1902) by which the U.S. gained control of the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Then, there were World Wars I and II, the Korean Police Action (1949 -- 1952), and the longest — and most expensive war — in American history, the Vietnam War between 1959 and 1975.

Meanwhile, between 1789 and 1945, there were at least 200 presidentially directed military actions all over the globe. Among other places, these military actions involved the shelling of Indochina in 1849 and the U.S. military occupation of virtually every Caribbean and Central-American country between 1904 and 1934. Indeed, in his effort to justify U.S. military intervention in Cuba against Fidel Castro, on September 17, 1962, Secretary of State Dean Rusk presented a list to a U.S. Senate Hearing of all of these 200 plus "precedents" (now called "low intensity conflicts") from 1789 to 1960.

During the Cold War between 1945 and 1989, the U.S. waged war, directly or through surrogates, openly and covertly, from military bases all over the world.

After the Cold War ended in 1989, other important military actions have been undertaken, such as the Gulf War (January and February 1991 in Iraq), in the former Yugoslavia (in 1999), and the 2001 war against the Taliban government and international terrorists in Afghanistan and the Philippines in 2003. To this roster, we must add the 2003 war against Iraq, to be followed, perhaps, by one with North Korea, which has lately brandished its nuclear weapons and missiles.

American historians have avidly studied war, especially the Civil War and World War II, but their focus has almost always been on war causation, battles, generalship, battlefield tactics and strategy, and so on. Overlooked, for the most part, are the general and specific effects of war upon American cultural life; the possible connections between war and civilian violence is still largely unexplored territory. Has war directly or indirectly encouraged an American predisposition toward aggressiveness and the use of violence or was it the reverse?

This question has never been satisfactorily investigated by American historians or other scholars. Yet, the overwhelming majority of historians have always known that America was — and is — a violent country. But they have said very little about it, depriving the population of a realistic understanding about this important aspect of their national culture. This omission is most clearly observable in U.S. history textbooks used in high schools, colleges and universities, on the one hand, and popular histories derived from these texts, on the other, which have never devoted serious attention to the topic of the violence in America, let alone sought to explain it.

Consequently, there seems little genuine understanding about the centrality of violence in American life and history.

The overwhelming majority of American historians have not studied, written about, or discussed America's "high violence" environment, not because of a lack of hard information or knowledge about the frequent and widespread use of violence, but because of an unwillingness to confront the reality that violence and American culture are inextricably intertwined.

Many prominent historians recognized this years ago.

In the introduction to his 1970 collection of primary documents, "American Violence: A Documentary History," two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Richard Hofstadter wrote: "What is impressive to one who begins to learn about American violence is its extraordinary frequency, its sheer commonplaceness in our history, its persistence into very recent and contemporary times, and its rather abrupt contrast with our pretensions to singular national virtue." Indeed, Hofstadter wrote the "legacy" of the violent 1960s would be a commitment by historians systematically to study American violence.

But most American historians have studiously avoided the topic or somehow clouded the issue. In 1993, in his magisterial study, "The History of Crime and Punishment in America," for example, Stanford University Historian Lawrence Friedman devoted a chapter to the many forms of American violence. Then, in a very revealing chapter conclusion, Friedman wrote: "American violence must come from somewhere deep in the American personality ... [it] cannot be accidental; nor can it be genetic. The specific facts of American life made it what it is ... crime has been perhaps a part of the price of liberty ... [but] American violence is still a historical puzzle." Precisely what is it that historians are unwilling to discuss? Basically, there are three forms of American violence: mob violence, interpersonal violence, and war.

What is the extent of mob violence?

Indiana University Historian Paul Gilje, in his 1997 book, "Rioting in America," stated there were at least 4,000 riots between the early 1600s and 1992. Gilje asserted that "without an understanding of the impact of rioting we cannot fully comprehend the history of the American people."

This is a position that director Martin Scorsese just made his own in the film, "Gangs of New York," which focuses on the July 1863 Draft Act Riots in New York City as the historical pivot around which America's urban experience revolved. However, occasional gory movie depictions of violent riots, or Civil War battles, as in "Gods and Generals," provide little real understanding of a nation's history.

M.I.T. Historian Robert Fogelson, in his 1971 book, "Violence as Protest: a Study of Riots and Ghettos," concluded that "for three and a half centuries Americans have resorted to violence in order to reach goals otherwise unattainable ... indeed, it is hardly an exaggeration to say that the native white majority has rioted in some way and at some time against every minority group in America and yet Americans regard rioting not only as illegitimate but, even more significant, as aberrant."

Part of the fascination with group violence is the spectacle of mob rampages. But for historians there is more; group violence is viewed as a "response" to changing economic, political, social, cultural, demographic or religious conditions. Thus, however violent the episodes were, historians could see larger "reasons" for these group behaviors; somehow, these actions reflected a "cause."

(This might be likened to the way many American historians still view the southern secession movement and Civil War. Seeking to maintain their institution of human slavery, southerners started the bloodiest war in American history which almost destroyed the union. But because they claimed to be fighting for their "freedom," historians have treated their action as a legitimate cause, whereas in other nations such action is ordinarily viewed as treason.)

Now, to the nitty-gritty: How many victims did riots and collective violence claim over the 400-year American historical experience?

This can never accurately be known, considering it includes official and unofficial violence against Native American Indians, African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, Asians and untold riots, vigilante actions and lynchings, among other things.

But a conservative guesstimate of, perhaps, about 2,000,000 deaths and serious injuries between 1607 and 2001 (or about 5,063 each and every year for 395 years) seems a reasonable — and quite conservative — number for analytical purposes, until more precise statistics are available.

At least 753,000 Native American Indians were the intended victims of warfare and genocide between 1622 and 1900 in what is now the United States of America, according to one scholar. The number for African-Americans might equal or exceed the estimate for the Indians, 750,000.

The total number of deaths for all other forms of collective violence seems well under 20,000. The greatest American riot, the New York City Draft Act riots of July 1863, resulted in between 105 and 150 deaths, while the major 1960s riots (Watts, Los Angeles, Newark, N.J., and Detroit, Mich., accounted for a total of 103 deaths, and the 1992 Los Angeles riot claimed 60 lives. The estimate of deaths from the 326 vigilante episodes is between 750 and 1,000. Approximately 5,000 individuals were known to have been lynched between 1882 and 1968, and about 2,000 more killed in labor-management violence.

Horrendous as this sounds — and it is horrendous — this 2,000,000 figure pales when compared to the major form of American violence which historians have routinely ignored until very recently. Historians of violence have largely ignored individual interpersonal violence, which, in sharp contrast to group violence, is very frequent, sometimes very personal — and far deadlier than group violence.

In 1997, two distinguished legal scholars, Franklin Zimring and Gordon Hawkins, compared crime rates in the G-7 countries (Canada, England, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United States) between the 1960s and 1990s in their book, "Crime Is Not The Problem: Lethal Violence In America Is." Bluntly, they stated their conclusion: "What is striking about the quantity of lethal violence in the United States is that it is a third-world phenomenon occurring in a first-world nation."

Instances of personal violence include but are not limited to barroom brawls, quarrels between acquaintances, business associates, lovers or sexual rivals, family members, or during the commission of a robbery, mugging, or other crime.

How does the carnage in this category contrast with the 2,000,000 victims of group violence between 1607 and 2001?

During the 20th century alone, well over 10 million Americans were victims of violent crimes — and 10 percent of them — or 1,089,616 — were murdered between 1900 and 1997. The "total" number of "officially reported" homicides, aggravated assaults, robberies and rapes between 1937 and 1970 was 9,816,646, but these were undercounts!

Every year during the 20th century at least 10 percent of the crimes committed have been violent crimes — homicides, aggravated assaults, forcible rapes and robberies. Between 1900 and 1997, there were 1,089,616 homicides. How were they murdered? 375,350 by firearms and the rest were due to other means, including beating, strangling, stabbing and cutting, drowning, poisoning, burning and axing.

Between 1900 and 1971, 596,984 Americans were murdered. Between 1971 and 1997, there were another 592,616 killed in similar ways.

More Americans were killed by other Americans during the 20th century than died in the Spanish-American war (11,000 "deaths in service"), World War I (116,000 "deaths in service"), World War II (406,000 "deaths in service"), the Korean police action (55,000 "deaths in service"), and the Vietnam War (109,000 "deaths in service") combined. ("Deaths in Service" statistics are greater than combat deaths and were used here to make the contrast between war and civilian interpersonal violence rates even clearer.)

So, what accounts for the American ability to overlook collective violence, interpersonal violence, and war?

The explanation lies, first, with historians' abdication of responsibility systematically to deal with the issue of violence in America ... and, second, with the American population's refusal directly to confront any very ugly reality — which came first I do not know. This is what historians refer to as "mutual causation."

There are, of course, several factors that have enabled Americans to overlook their violent past. Many of these were actually defined by Richard Hofstadter in his 1970 introduction to "American Violence: A Documentary History." First, Americans have been told by historians that they are a "latter-day chosen people" with a providential exemption from the woes that plagued all other human societies. Historians of the 1950s had not denied that America's past was replete with violence; they just preferred during the Cold War to emphasize a more positive vision of America. Historians refer to this as the "myth of innocence" or the "myth of the new world Eden."

In an open, free, democratic society, graced with an abundance of natural resources, and without the residue of repressive European institutions, virtually any white person who worked hard had the opportunity to achieve the "American Dream" of material success and respectability.

Violence, especially political violence when it erupted, was dismissed out of hand as somehow "un-American," an unfortunate by-product of temporary racial, ethnic, religious and industrial conflicts.

Second, American violence had not been a major issue for federal, state or local officials because it was rarely directed against them; it was rarely revolutionary violence. Rather, American violence has almost always been citizen-against-citizen, white against black, white against Indian, Protestant against Catholic or Mormon, Catholic against Protestant, white against Asian or Hispanic.

The lack of a violent revolutionary tradition in America is the principal reason why Americans have never been disarmed, while in every European nation the reverse is true.

So, for the most part, Americans, laymen and historians alike, have been able to practice what some historians have termed "selective" recollection or "historical amnesia" about the violence in their past and present. Since the 1960s, historians' works, cumulatively, have demonstrated a causal connection between American culture and the American predisposition to use violence. We might now be experiencing yet another by-product of this national penchant for violence — a willingness to engage in a major war without asking very many hard questions. It's the American Way.

Ira M. Leonard has been a professor of history at Southern Connecticut State University for over 30 years. This article is adapted from a speech presented to the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences in January 2003.

Pundits agree: America is violent

Others agree that America's culture is especially, even uniquely, violent. Consider the following excerpt from a Yellow Times column:

"Gun control is silly"

Printed on Wednesday, October 16, 2002 @ 00:10:26 EDT

By Paul Harris

YellowTimes.org Columnist (Canada)

On a per capita basis, there are more weapons in Canada than in the U.S. That statistic staggered me and made me seriously rethink the sanity of my countrymen but it is worth noting that while we may own the damn things, we don't seem to have much desire to blow other people away with them. Why is that? Why are Americans, who are largely from the same immigrant stock as us with similar social systems and similar views on so many issues, a substantially more violent society?

It isn't just the guns; look around. Look at the glorious Hollywood efforts designed to show us all the really neat ways people can be killed and that stuff can 'blow up real good" (to quote John Candy); look at the violence in your other forms of entertainment such as the simulated murder in video games and paintball; look at the violence inherent in your sporting activities; look at the violence of the founding of your nation, your civil war, the violence that arises because you spent so long enslaving a large portion of your population; the violence that is inherent in your callous disregard for the weakest members of your society.

Look at America's history of conflict. Since World War II, the United States has attacked or had wars with: China (45-46), Korea (50-53), Guatemala (54, 67-69), Cuba (59-60), Belgian Congo (64), Vietnam (61-73), Cambodia (69-70), Grenada (83), Libya (86), El Salvador (80-92), Nicaragua (81-90), Panamá (89), Iraq (91), Bosnia (95), Sudan (98), Yugoslavia (99), Afghanistan (01-02), and almost surely Iraq is on the horizon again. Add to this incursions into Colombia, Chile, etc. and it's pretty evident that as a nation, you folks are really into killing. And your leaders still have the balls to tell the world that you are a nation of peace lovers.

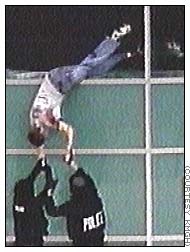

When one of your citizens goes off his nut (and it usually is a man), your media almost befriends the thug with the cute way they come up with nicknames for him: the Hillside Strangler, the Boston Strangler, the Beltway Sniper, the POTUS, and so on. The guy gets the glory he's seeking, CNN and that crowd gets to obsess over something new for a while, and eventually life goes back to just blowing up other countries until a new thug appears.

Another writer goes straight to the emotional core of America's death-dealing mentality. From the LA Times, 5/2/99:

Life is Precious—or It's Not

Violence: When our presidents and film heroes solve problems by killing people, what do we expect from our children?

By BARBARA KINGSOLVER

In the aftermath of the high school killings in Littleton, Colo., we have the spectacle of a nation acting baffled. Why would any student, however frustrated with mean-spirited tormentors, believe that guns and bombs are the answer?

If we're really interested in this question, we might have started asking it awhile ago. Why does a nation persist in celebrating violence as an honorable expression of disapproval? In, oh let's say, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Sudan, Waco—anywhere we get fed up with mean-spirited tormentors—why do we believe guns and bombs are the answer?

Let's not trivialize a horrible tragedy by pretending we can't make sense of it. "Senseless" sounds like "without cause," and requires no action. After an appropriate interval of dismayed hand-wringing, we can go back to business as usual. What takes guts is to own up: This event made perfect sense. Children model the behavior of adults, on whatever scale is available to them. Ours are growing up in a nation whose most important, influential men—from presidents to film heroes—solve problems by killing people. It's utterly predictable that some boys who are desperate for admiration and influence will reach for guns and bombs. And it's not surprising that it happened in a middle-class neighborhood; institutional violence is right at home in the suburbs. Don't point too hard at the gangsta rap in your brother's house until you've examined the Pentagon in our own. The tragedy in Littleton grew straight out of a culture that is loudly and proudly rooting for the global shootout. That culture is us.

It may be perfectly clear to you that Nazis, the Marines, "the Terminator" and the N.Y.P.D. all kill for different reasons. But as every parent knows, children are good at ignoring or seeing straight through the subtleties we spin.

Here's what they see: Killing is an exalted tool for punishment and control. Americans who won't support it are ridiculed. Let's face it, though, most Americans believe bloodshed is necessary for preserving our way of life, even though this means we risk the occasional misfire—the civilians strafed, the innocent man wrongly condemned to death row.

If this is your position, I wonder if you'd be willing to go to Littleton and explain to some mothers about acceptable risk. In a society that embraces violence, this is what "our way of life" has come to mean. We have taught our children in a thousand ways, sometimes with flag-waving and sometimes with a laugh track, that the bad guy deserves to die. But we forgot something. Any of our children may someday be, in someone's mind, the bad guy.

If you want the loss of these precious lives in Littleton to mean something, use it to nail a permanent benchmark into your own heart: Life is that precious, period. Establish zero tolerance for murder as a solution to anything. Start by removing from your household and your life every television program, video game, film, book, toy and CD that presents the killing of humans (however symbolic) as an entertainment option. Then move on to harder things. Force yourself to discuss the moral lessons of capital punishment. Demand from your elected officials diplomacy instead of a war budget. Look into what we did (and are still doing) to the living souls of Iraq, if you can bear it. Tell your kids, and someone else's, that you're not proud of our country's history of bombing people in nations we disdain.

Sound extreme? Don't kid yourself. Death is extreme, and the children are paying attention.

In the same vein, Al Martinez, LA Times columnist, wrote the following, 3/29/01:

[Corona del Mar school board member Serene] Stokes is a bright, caring lady who loves her children and her grandchildren and believes fiercely in the need to create a safe environment for the 22,000 students in her district.

But the problem facing school boards across the country, is that we're looking for bullies in all the wrong places. Schools can educate, warn, and hug the kids until they're bug-eyed, but that's only going to help a little bit. We're the real bullies.

Through merchandising and manipulation, we bully vulnerable, uninformed children into believing guns are cool, violent movies are cool, hate-filled lyrics are cool, bloody video games are cool, and smashing, crippling confrontations in sports are maybe not cool but at least fun to watch.

We call upon teens and preteens to grow up too soon, before they can perceive the line between fantasy and reality, and then we sob and wring our hands and wonder what went wrong when they cross the line.

We went wrong. We're still going wrong. Society is the biggest bully of all, shielding by 1st and 2nd Amendments the purveyors of violence who profit at the expense of the human dignity that Stokes was talking about. No school district policy is about to change that.

To paraphrase Pogo, we has met the bully and he is us. And ain't that too damned bad?

From an article titled "Grim Show Is Only the Latest for America's Violent Culture" in the LA Times, 4/22/99:

"We are obsessed with violence as a people, and, even though we wring our hands, they're covered with blood," said Richard Slotkin, a Wesleyan University history professor and author of "The Myth of the Frontier in 20th Century America."

"We're shocked by images from Littleton, but bombing Belgrade is OK. We're against the nanny, but we're entertained by the Western. There are serious moral and political issues here, and yet this country hasn't begun to sort them out."

.

.

.

"We have a long history of permissive views towards guns in America and the use of weapons to settle scores," he added. "And even though we complain about this, we as a people are still not sure we want to give up our right to kill someone."

America's mythical warriors

It's not enough that America is perhaps the most violent, warlike nation in history. Some people (conservatives) worry that by giving rights to women and minorities...by negotiating with foreigners and other enemies...we're weakening our historical resolve. For example, alleged Indian David A. Yeagley once wrote, "Americans nowadays seem to be forgetting what it means to be a warrior."

Not to worry, Yeagley. Our warrior mentality is intricably woven into our history of conquest and genocide. Our culture has exalted the warrior-hero since the beginning, and our myth-making apparatus still creates warrior-heroes for us to worship.

The Americans are certainly hero-worshippers, and always take their heroes from the criminal classes.

Oscar Wilde, letter, April 19, 1882

Forgetting what it means to be a warrior? Tell that to everyone who loves Eminem, heavy metal, sports stars (who are routinely called warriors or gladiators), pro wrestlers, Clint Eastwood, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Colin Powell, or "President" Bush. Even Yeagley mentioned Xena in his essay—a fictional warrior along with the Ninja Turtles, the Power Rangers, the Punisher, Gladiator, Pokémon trainers, and Lara Croft: Tomb Raider. Our society continues to glorify warriors as much as ever.

Warriors are who we mythologize in our culture. Knights in shining armor, Robin Hood, the Three Musketeers, Zorro, Natty "Hawkeye" Bummpo, the Minutemen, Daniel Boone, Andrew Jackson, Civil War generals (Grant, Lee, Stonewall Jackson), Col. Custer, Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley, Sgt. York, the Untouchables, WW II generals (Patton, McArthur, Eisenhower)...the list goes on and on. If a non-military hero refuses to fight, as with Charles Lindbergh and his isolationist views, America turns on him with a vengeance.

A book review in the LA Times, 1/7/01, notes our myth-making tendency:

Why have so many violent but otherwise marginal figures from the frontier—James Bowie and his knife, the Indian-killing

Kit

Carson, Jesse James, Billy the Kid, John Henry "Doc" Holliday, Wyatt Earp and his brothers, Calamity Jane, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid—entered into American folklore and been celebrated in numerous films, even musical comedies, while the governors, the senators, the entrepreneurs, the founders of cities and towns from the same time lie in their graves forgotten?...Why do we remember the 1920s and 1930s in terms of Al Capone, the St. Valentine's Day Massacre, Bonnie and Clyde, George "Machine Gun" Kelly, Charles Arthur "Pretty Boy" Floyd, Ma Barker, Dutch Schultz and Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel when we would be hard-pressed to name a roster of brain trusters from the New Deal?

The answer is obvious. We define ourselves as warriors—warriors for truth, justice, and the American way. Warriors for peace, even, if that isn't a stupid contradiction. It's been that way since the first European saw the first Indian and decided he needed smiting in the name of God.

Far from forgetting what it means to be a warrior, we've enshrined the notion. Our warrior history—the Founding Fathers and the American Revolution, Honest Abe and the Civil War, the "greatest generation" and World War II—is the subject of countless books, movies, and reenactments. Our national "tragedy" occurred in Vietnam, where we learned we weren't the invincible warriors we thought we were.

From the first Indian wars with the Pequots to the latest assaults on Iraq, Somalia, and Bosnia, we've always used war as the final solution. Some of these wars were necessary, but many weren't. The point isn't that we fight wars, but that we revel in them. We're proud of, not disgusted by, how bellicose we are.

The following is an expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular mini-essay in Terrorism: US Against Them. As we embark on the 21st century, as the world's military-industrial superpower, it's clear we haven't forgotten how to be warriors. If anything, we're too steeped in our warrior mentality.

America, the warrior society

In 2001, George W. Bush cast the battle against terrorism in comic-book terms: good vs. evil. He and others said we must be strong, like John Wayne or Superman. But some examples suggest we may be "strong" enough already:

- A dozen football players died the summer of '01 after thinking they had to work out in enervating heat and take ephedrine supplements to win.

- American heroes and superheroes declare villains "sick," "mad" or "evil" and pummel them without trying to understand them.

- Schools "honor" Indians by casting them as vanquished-warrior mascots while ignoring their real economic and social problems today.

- Our national anthem is a tortured martial strain honoring victory in war. Americans sing daily of "rockets' red glare" and "bombs bursting in air."

- After onlookers urged a Seattle woman to jump off a bridge, a columnist wrote, "Given that nearly every person suffers romantic rejection, threatening suicide over this loss is the action of a profoundly immature individual." (Dennis Prager, LA Times, 9/10/01)

- Dale Earnhardt died after he and other NASCAR drivers decided they were too tough to use restraint harnesses that prevent head and neck injuries.

- Popular "reality" TV shows—Survivor, Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, The Weakest Link, Big Brother—foster a competitive, winner-takes-all mentality.

- Outraged and unable to cope through reason, lone gunmen shoot their lovers or employers to validate themselves almost every day.

- For a football game between Florida and Florida State, the Tallahassee Democrat ran a front-page banner headline proclaiming "WAR" (11/30/96). The sub-headline, "D-Day at Doak," was set against a backdrop of dripping red ink.

- After visiting LA's Museum of Tolerance, Andrew Franks, 11, who identified himself as "Spanish, Indian, and American," said he liked "where they showed all the stuff they used to kill." (LA Times, 9/11/01)

This chest-pounding machismo is central to the American mindset. Bush proclaimed us the "brightest beacon of freedom and opportunity" after the devastation, once again touting our superiority to everyone else. Sadly, he doesn't get that our capitalist, cultural aggression is exactly what anti-Americans are protesting.

When will we learn that a starving baby in a developing country doesn't need abstractions like freedom or opportunity? It needs a roof overhead and food on the table—i.e., security, not "freedom." How hard is that to understand?

Traditional Indian societies offered a balance between communal security and individual freedom. So do most of the planet's cultures today. America is alone at the "freedom" extreme, imagining "the individual as solitary gunslinger and society as a hostile frontier."

If we've forgotten our warrior past—as Yeagley wrongly claimed—would that be so bad? The American warrior mentality, as embodied in John Wayne and other gunslingers, is exactly what led to the continent's colonization and Native people's confinement. Might a less warlike attitude have led to more humane results?

More on America's machismo

War song of America the strong

Dubya-speak: justice means killing people

Kill those towelheads!

"Real men" carry "big sticks"

Yeagley inadvertently hinted at the real problem when he wrote about gun control: "[T]hat's not the Indian way. That's not the way of a man." A man is a warrior, he implied, and a warrior is someone with a gun. And anyone who's studied Freud knows what a gun is.

What's the corollary to Yeagley's position? If you're not a man, you must be a woman, right? Or should I say a squaw? The ultimate insult in our society is to call someone gay—i.e., to question his manhood.

I've knocked this manhood argument before. See X-Men: All-New or Same-Old? for one example. The issue comes up over and over in popular culture, where our heroes solve their problems with guns and fists.

Some postings shed light on Yeagley's macho attitude. First, an excerpt from an op-ed column by Robert S. McElvaine, professor of history at Millsaps College. From the LA Times, 2/21/01:

Insecure masculinity has...been a major force in history. Sexually insecure men often seek validation of their manhood by pursuing power. "But he was a man!" a trembling Richard M. Nixon affirmed of Theodore Roosevelt as Nixon concluded his rambling talk to the White House staff at the time of his resignation in 1974. There can be little doubt that the disgraced president had himself in mind as he referred to this particular predecessor.

Insecure masculinity was a major motivation for several other 20th century presidents, from Teddy Roosevelt at the century's beginning to Bill Clinton at its end. The Republican Roosevelt is a prime example. One reason for Roosevelt's concern about proving his manhood was his feeling of shame that his father had paid for a substitute to fight in his place during the Civil War. Roosevelt spoke of almost everything in sexual terms. He said war was a necessary arena for the display of "manly virtues" and frequently referred to adversaries as "eunuchs" or "impotent." And it does not take a Freudian imagination to understand why Roosevelt used the "big stick" as his metaphor for military might.

Similar anxieties appear to have driven John F. Kennedy and his disciple Clinton to try to show their manhood by treating women as disposable playthings. And it could be argued that Lyndon B. Johnson took the nation into a war that he knew would be disastrous partly out of a desire to prove his manhood. "There's not anything that'll destroy you as quick as pulling out," Johnson told Sen. Richard Russell in 1964. "They'll forgive you anything except being weak. We've got to conduct ourselves like men." As had Roosevelt, Johnson often described male opponents of his war policy by names that indicated they were like women.

From Robert Scheer's column in the LA Times, 10/29/02:

The macho mouths whose combat experience most often consists of battles for talk-show ratings would have you believe that it takes great courage to bang the drums of war, whereas it is cowardly to speak the language of peace and diplomacy. "I'm sick and tired of those old men dreaming up wars for young men to die in," [George] McGovern said in an interview. "You know that [Vice President] Dick Cheney, [Defense Secretary] Donald Rumsfeld and [Deputy Defense Secretary] Paul Wolfowitz have not been in a war and will not fight in this one they are planning."

George W. Bush hasn't been in a war either, of course. He dodged Vietnam by enlisting for a cushy stateside position in the National Guard. So much for America's brave and bold leaders as the new century unfolds.

War in general and the wars on terror and Iraq in particular provide many examples of machismo in action. Consider the sexual and homoerotic overtones of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal, for instance. Or this note from Parade Magazine, 11/28/04:

After more than a year in Iraq, the U.S. Army has officially renamed 17 of its bases around Baghdad to sound, well, a lot less warlike.

The old names: Steel Dragon, Headhunter, Banzai, Warhorse, and Gunslinger. The new names: Honor, Independence, Justice, Freedom, and Solidarity. Gee, I can't imagine why Iraqis thought American soldiers were swaggering bullies and thugs.

Bush as Rambo

Bush isn't letting his record of shirking duty stop him. Oh, no...far from it. He and his right-wing propaganda machine (including the so-called liberal media) have cranked up the efforts to portray him as the second coming of Jesus, John Wayne, and Rambo. In other words, as the quintessential American: righteous, godlike, indomitable.

Paul Krugman explains this in a column titled The Rambo Coalition in the NY Times, 8/24/04:

One of the wonders of recent American politics has been the ability of Mr. Bush and his supporters to wrap their partisanship in the flag. Through innuendo and direct attacks by surrogates, men who assiduously avoided service in Vietnam, like Dick Cheney (five deferments), John Ashcroft (seven deferments) and George Bush (a comfy spot in the National Guard, and a mysterious gap in his records), have questioned the patriotism of men who risked their lives and suffered for their country: John McCain, Max Cleland and now John Kerry.

How have they been able to get away with it? The answer is that we have been living in what Roger Ebert calls "an age of Rambo patriotism." As the carnage and moral ambiguities of Vietnam faded from memory, many started to believe in the comforting clichés of action movies, in which the tough-talking hero is always virtuous and the hand-wringing types who see complexities and urge the hero to think before acting are always wrong, if not villains.

After 9/11, Mr. Bush had a choice: he could deal with real threats, or he could play Rambo. He chose Rambo. Not for him the difficult, frustrating task of tracking down elusive terrorists, or the unglamorous work of protecting ports and chemical plants from possible attack: he wanted a dramatic shootout with the bad guy. And if you asked why we were going after this particular bad guy, who hadn't attacked America and wasn't building nuclear weapons -- or if you warned that real wars involve costs you never see in the movies -- you were being unpatriotic.

As a domestic political strategy, Mr. Bush's posturing worked brilliantly. As a strategy against terrorism, it has played right into Al Qaeda's hands. Thirty years after Vietnam, American soldiers are again dying in a war that was sold on false pretenses and creates more enemies than it kills.

Krugman continues explaining why Americans have rallied behind their macho man in a column titled A Mythic Reality. In the NY Times, 9/7/04:

The best book I've read about America after 9/11 isn't about either America or 9/11. It's "War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning," an essay on the psychology of war by Chris Hedges, a veteran war correspondent. Better than any poll analysis or focus group, it explains why President Bush, despite policy failures at home and abroad, is ahead in the polls.

War, Mr. Hedges says, plays to some fundamental urges. "Lurking beneath the surface of every society, including ours," he says, "is the passionate yearning for a nationalist cause that exalts us, the kind that war alone is able to deliver." When war psychology takes hold, the public believes, temporarily, in a "mythic reality" in which our nation is purely good, our enemies are purely evil, and anyone who isn't our ally is our enemy.

This state of mind works greatly to the benefit of those in power.

One striking part of the book describes Argentina's reaction to the 1982 Falklands war. Gen. Leopoldo Galtieri, the leader of the country's military junta, cynically launched that war to distract the public from the failure of his economic policies. It worked: "The junta, which had been on the verge of collapse" just before the war, "instantly became the saviors of the country."

The point is that once war psychology takes hold, the public desperately wants to believe in its leadership, and ascribes heroic qualities to even the least deserving ruler. National adulation for the junta ended only after a humiliating military defeat.

George W. Bush isn't General Galtieri: America really was attacked on 9/11, and any president would have followed up with a counterstrike against the Taliban. Yet the Bush administration, like the Argentine junta, derived enormous political benefit from the impulse of a nation at war to rally around its leader.

Another president might have refrained from exploiting that surge of support for partisan gain; Mr. Bush didn't.

And his administration has sought to perpetuate the war psychology that makes such exploitation possible.

Step by step, the fight against Al Qaeda became a universal "war on terror," then a confrontation with the "axis of evil," then a war against all evil everywhere. Nobody knows where it all ends.

What is clear is that whenever political debate turns to Mr. Bush's actual record in office, his popularity sinks. Only by doing whatever it takes to change the subject to the war on terror -- not to what he's actually doing about terrorist threats, but to his "leadership," whatever that means -- can he get a bump in the polls.

Last week's convention made it clear that Mr. Bush intends to use what's left of his heroic image to win the election, and early polls suggest that the strategy may be working. What can John Kerry do?

Campaigning exclusively on domestic issues won't work. Mr. Bush must be held to account for his dismal record on jobs, health care and the environment. But as Mr. Hedges writes, when war psychology makes a public yearn to believe in its leaders, "there is little that logic or fact or truth can do to alter the experience."

To win, the Kerry campaign has to convince a significant number of voters that the self-proclaimed "war president" isn't an effective war leader -- he only plays one on TV.

Another pundit thinks Bush resembles another infamous American warrior:

Bush's Last Stand

September 28, 2004

By Steven Vincent

President Bush likes to think of himself as a "war President," who is "resolute," "steadfast," and "decisive." He also likes to compare himself to historical figures. His favorite is Winston Churchill who led Great Britain through the horrors of World War II.

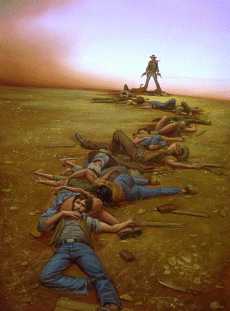

I believe a comparison to a historical figure is appropriate but I think he is much more like a famous American military leader -- General George Armstrong Custer.

Like George W. Bush, George A. Custer was born to a privileged family. He used his family's political connections to get into West Point, an institution of learning he was not otherwise qualified for. While at West Point, George did not distinguish himself among his 34 classmates.

His carefree attitude and joking demeanor did not sit well with the rigid requirements of military school life. He was often punished and, at one point, received enough demerits to be expelled. Someone was watching out for young George though and his demerits were mysteriously removed from the record, allowing him to continue.

Cadet George Custer graduated from West Point 34th out of 34, last of his class. He was nearly court-martialed for neglect of duties while still at West Point awaiting his commission but again, somehow, skated by without punishment -- a now recurring theme in George's life.

Despite his poor grades and inability to grasp basic military requirements, George was given a plumb assignment in the military during the Civil War. The units he commanded suffered unusually high casualty rates even by the standards of the time due to George's arrogance, brazen aggression and disregard for his men's safety.

In late 1867 Custer was court-martialed and suspended from duty for a year for being absent from duty but he used his connections to, once again, skirt punishment and regain his standing in the military. General Phil Sheridan used his military power to excuse young George's youthful mistake and brought him back into a position with more power and authority.

George was a master of military politics and somehow worked his way up to Brigadier General at the age of 25, the youngest man ever to attain that rank. Gen. George was placed in command of a contingent of men to seek out "renegade" Indians who were holding up the "progress" of miners and other business venturers from gaining profit off of the unexplored lands. The Natives were portrayed as vicious savages intent on killing innocent American civilians though the majority of them just wanted to live their lives in peace in their homelands.

George's fate and historical fame were both wrapped up in an expedition to destroy the Lakota, Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians in Montana because of the wrongful association of all of the tribes in that area with the attacks by one tribe and chief, Crazy Horse. The U. S. government, in all of its wisdom, decided to round up, imprison or destroy all of the Native people in that area and they relied on their young, brash, arrogant commander to do it.

Riding with his men and two other brigades, the plan was to use overwhelming force to destroy the less well-armed and organized Indians. Young and boastful, George knew that this mission would ensure his fame, fortune and political future for all time and led his men into battle in spite of the intelligence he was getting from the field.

Though he was warned in advance by scouts that the Indians had a much larger force than was originally thought, he continued his march.

Though allied units commanded by far more experienced leaders fell behind and were not with him, he pushed forward, resolute.

Though he split his forces into three separate units, weakening them, he rode ahead, confidently. Though he went into battle with underwhelming force, he did so convinced of his ability to bring forth a glorious victory for his country and himself.

Convinced of his own superiority and leadership skills, George pushed valiantly forward into one of the greatest military blunders in U.S. history. The Indians, formerly opponents of each other, united against the vicious attacks of the U.S. military and thousands of former enemies combined their forces to attack George and his troops.

General George Armstrong Custer led all of his men, cocksure, to slaughter. Not one soldier under his command survived his confident, resolute, and blindingly wrong blunder.

The amazing thing is, there are still George defenders who claim he was a great leader and military mind. In spite of evidence to the contrary, he will always, in some minds, be considered a brave patriot whose confidence, resoluteness, and conviction in his decision-making outweigh the ultimate result of his foolish choices.

But while there are many historical similarities between the two Georges, there is one glaring difference.

One George led his men into battle and faced the bullets and arrows of the enemy, donned the uniform and fought for his country, led his men from the front, and stood behind his choices personally and was forced to accept their fatal outcome.

The other is our President.

Who best embodies our national attitude of "shoot first, ask questions later"? Andrew Jackson, George A. Custer, Teddy Roosevelt? John Wayne, Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush? Dirty Harry, Rambo, the Terminator? Take your pick.

What are men afraid of?

More on America's fear of seeming effeminate:

Wimps, wussies and W.

How Americans' infatuation with masculinity has perilous consequences.

By Mark Dery, MARK DERY is a cultural critic who teaches in the department of journalism at New York University.

May 3, 2007

SO THERE'S a smoking crater where Don Imus used to sit. That's fine with those of us who never understood the appeal of his grizzled-codger shtick, which always sounded like Rooster Cogburn reading "The Turner Diaries" anyway.

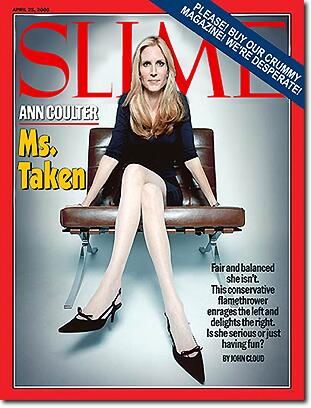

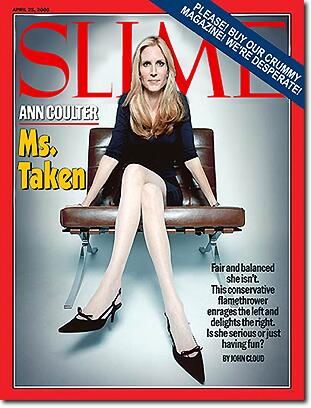

But if we're going to administer a ritual flaying to every blowhard who channels the ugly American id, why has a hate-speech Touretter like Ann Coulter escaped the skinning knife? She called Democratic presidential candidate John Edwards a "faggot" at the Conservative Political Action Conference; insisted on "The Big Idea with Donny Deutsch" that Bill Clinton's "promiscuity" is proof of "latent homosexuality"; quipped on "Hardball Plaza" that Al Gore is a "total fag"; and wrote, in her syndicated column, that the odds of Hillary Clinton "coming out of the closet" in 2008 are "about even money."

Obviously, racism — slavery, lynching, institutionalized discrimination — has taken a much greater toll, in this country, than homophobia. According to the most recent FBI data (2005), most hate crimes (54.7%) were racially motivated; only 14.2% were inspired by the sexual orientation of the victim.

But there's another reason the media haven't given Coulter a prime-time water-boarding: Her problem is our problem. As a society, we view racial epithets as Class A felonies, whereas homophobic slurs are parking violations (if that). Coulter laughed off her Edwards crack, saying, "The word I used … has nothing to do with gays. It's a schoolyard taunt, meaning wuss."

Got that? The term "faggot," helpfully defined by the American Heritage Dictionary as "offensive slang … a disparaging term for a homosexual man," really means "wuss," a schoolyard pejorative applied exclusively to guys — guys who are "unmanly," according to American Heritage. Not that it means you're a fag or anything. Which is just British slang for "cigarette" anyway. So why are you looking at me like that?

Coulter's chop-logic reminds us that homophobia is so ubiquitous as to be invisible in American society. Only people whose idea of formal attire is a white sheet with eyeholes would dare to use the N-word in public, but homophobic smears reverberate throughout pop culture. Little wonder: Asked in a 2003 Pew Global Attitudes Project study if homosexuality should be accepted by society, only a razor-thin majority (51%) of Americans answered yes, in contrast to 83% in Germany, 77% in France and 74% in Britain.

Our tradition of demonizing political opponents is founded on homophobic innuendo. Camille Paglia derided Al Gore for his "prissy, lisping Little Lord Fauntleroy persona" that "borders on epicene." John Kerry was deemed too "French" — meaning too much of a girlie man — to be commander in chief. Now Edwards is too heteroflexible; only Straight Guys with a Queer Eye get $400 haircuts, right?

George W. Bush learned an unforgettable lesson about the anxious nature of American masculinity when Newsweek branded his father a "wimp," a perception Bush 41 never really overcame. The resolve never to look like a wimp is the key to Dubya's psychology: the you-talkin'-to-me pugnacity at news conferences; the Top Gun posturing on the aircraft carrier, in a crotch-gripping flight suit that moved G. Gordon Liddy to swoon — on "Hardball," for Freud's sake — "what a stud."

Doesn't all this machismo and locker-room homophobia protest a little too much? What can we say about a country so anxiously hypermasculine that it produces Godmen, a muscular-Christianity movement that seeks to lure Real Men back to church with services that feature guys bending metal wrenches with their bare hands and leaders exulting, "Thank you, Lord, for our testosterone!"

The trouble with manhood, American-style, is that it's maintained by frantically repressing every man's feminine side and demonizing the feminine and the gay wherever we see them. In his book, "The Wimp Factor: Gender Gaps, Holy Wars, and the Politics of Anxious Masculinity," clinical psychologist Stephen Ducat calls this state of mind "femiphobia" — a pathological masculinity founded on the subconscious belief that "the most important thing about being a man is not being a woman."

OK, so maybe I'm overstepping the bounds of my Learning Annex degree in pop psychology. But the hidden costs of our overcompensatory hypermachismo are far worse than a few politicians slimed by pundits. The horror in Iraq has been protracted past the point of lunacy by George W.'s bring-it-on braggadocio, He-Ra unilateralism and damn-the-facts refusal to acknowledge mistakes — all hallmarks of a pathological masculinity that confuses diplomacy with weakness and arrogant rigidity with strength. It is founded not on a self-assured sense of what it is but on a neurotic loathing of what it secretly fears it may be: wussy. And it will go to the grave insisting on battering-ram stiffness (stay the course! don't pull out!) as the truest mark of manhood.

Woman's touch needed

As the pundits suggest, our culture is predominantly masculine. We train our children to think and solve problems in masculine ways. Like the mothers in Barbara Kingsolver's column, if a women were in charge, she might handle problems very differently.

Yes, perhaps a less macho mentality might serve the world better. An excerpt from the LA Times, 3/15/05:

COMMENTARY

The Feminine Technique

Men attack problems. Maybe women understand that there's a better way.

By Deborah Tannen

Deborah Tannen, a professor of linguistics at Georgetown University, is the author of "The Argument Culture" (Random House, 1998).

There is plenty of evidence that men more than women, boys more than girls, use opposition, or fighting, as a format for accomplishing goals that are not literally about combat — a practice that cultural linguist Walter Ong called "agonism," from the Greek word for war, agon.

Watch kids of any age at play. Little boys set up wars and play-fights. Little girls fight, but not for fun. Starting a fight is a common way for boys to make friends: One boy shoves another, who shoves back, and pretty soon they're engaged in play. But when a boy tries to get into play with a girl by shoving her, she's more likely to try to get away from him. A recent New Yorker cartoon captured this: It showed a little girl and a little boy eyeing each other. She's thinking, "I wonder if I should talk to him." He's thinking, "I wonder if I should kick her."

Older boys have their own version of agonism, using fighting as a format for doing things that have nothing to do with actual combat: They show affection by mock-punching, getting a friend's head in an armlock or playfully trading insults.

Here's an example that one of my students observed: Two boys and a girl are building structures with blocks. When they're done, the boys start throwing blocks at each other's structures to destroy them.

The girl protects hers with her body. The boys say they don't really want their own creations destroyed, but the risk is worth it because it's fun to destroy the other's structures. The girl sees nothing entertaining about destroying others' work.

Arguing ideas as a way to explore them is an adult version of these agonistic rituals. Because they're used to this agonistic way of exploring ideas — playing devil's advocate — many men find that their adrenaline gets going when someone challenges them, and it sharpens their minds: They think more clearly and get better ideas. But those who are not used to this mode of exploring ideas, including many women, react differently: They back off, feeling attacked, and they don't do their best thinking under those circumstances.

This is one reason many women who are talented and passionate lovers of science drop out of the profession. It's not that they're not fascinated by the science, don't have the talent to come up with new ideas or are not willing to put long hours into the lab, but that they're put off by the competitive, cutthroat culture of science.

The assumption that fighting is the only way to explore ideas is deeply rooted in Western civilization. It can be found in the militaristic roots of the Christian church and in our educational system, tracing back to all-male medieval universities where students learned by oral disputation.

Ong contrasts this with Chinese science and philosophy, which eschewed disputation and aimed to "enlighten an inquirer," not to "overwhelm an opponent." As Chinese anthropologist Linda Young showed, Chinese philosophy sees the universe in a precarious balance that must be maintained, leading to methods of investigation that focus more on integrating ideas and exploring relations among them rather than on opposing ideas and fighting over them.

Cultural training plays a big role too. Mediterranean, German, French and Israeli cultures encourage dynamic verbal opposition for women as well as men. Japanese culture discourages it for men as well as women. Perhaps that's why Japanese talk shows rarely include two guests (they'll have one or three or more), to avoid the polarized debates that our talk shows favor.

From a letter in the LA Times, 1/3/03:

I agree the violent world needs a woman's touch. I suggest an approach that might actually create real change in this world rather than continue this cycle of violence. Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910) in her Mother's Day Proclamation calls for women to arise: "Say firmly: We will not have great questions decided by irrelevant agencies. Our husbands shall not come to us reeking with carnage, for caresses and applause. Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy and patience. We women of one country will be too tender of those of another country to allow our sons to be trained to injure theirs."

The contrary argument is that violence is endemic to humans, men and women alike. But the scientific evidence doesn't necessarily agree. Consider the following excerpt from "Default Thinking Often a Wrong Path to Truth" by K.C. Cole. In the LA Times, 7/8/02:

Some argue that the default state of the human species is war. When we don't know what else to do, we fight. However, a recent study by UCLA psychologists throws this into doubt.

True, men under stress do tend to fall back on "fight or flight" as the first line of defense. Their default state is: hide, or hit someone. Women, however, cope with stress quite differently. They seek social contact or turn to nurturing—pick up the phone or tend the children. In fact, what principal investigator Shelley Taylor called this "tend and befriend" strategy for coping with stress seems characteristic of females of many species.

No one had seen this pattern before, Taylor said, because, until recently, most studies focused on males—the universal default mode.

Given that the world is run mostly by men, however, it's going to take no small amount of imagination to think outside this particularly lethal box. Certainly, it's happened before. Against all odds, there is quasi-democracy in Russia, quasi-peace in Northern Ireland; Nelson Mandela prevailed in South Africa and even Richard Nixon went to China.

Default is not the only option. In fact, Taylor and colleagues conclude that the "tend and befriend" strategy might well be responsible for the fact that women live on average 7 1/2 years longer than men.

And please, let's not talk about women like Margaret Thatcher or Condoleezza Rice. They've had to act macho to succeed in a macho world. Cole is suggesting what would happen if we embraced our feminine side and elected someone who embodied them to lead us. You know, a peacemaker—someone like Mohandas Gandhi or Martin Luther King.

Dr. Joyce speaks

Even Dr. Joyce Brothers, not normally the most perspicacious of observers, has noticed something "special" about America. Here's an exchange from her 2/13/00 column:

Before I came to this country, I taught in France. My kids played hard, but they just didn't seem to be as angry or violence-prone as youngsters in this country are....[D]o you have any possible explanation?

—B.L.

Dear B.L.: I don't think you are wrong in your perception of this problem, and there are a number of possible explanations. I believe that the great emphasis we put on freedom and independence is frequently misunderstood and misinterpreted. A sense of freewheeling frontier justice, where it's every man for himself, still seems to be with us.

Also, because we place so much emphasis both on winning and on equality, those who aren't winning, those who aren't getting a slice of our great national prosperity, feel cheated and angry....Add to all this the easy access to guns and the frequent examples of violence on playing fields and in the the media—and we seem to reward it, even though publicly we deplore it.

This is about as succinct a summary of the problem as you'll get. America's cultural bias...fueled by guns and the media...causes violence. Other cultures may have the masculine sense of entitlement...or readily available guns...or ultra-violent media products, but only America has the unique combination of factors.

Related links

Right-wing extremists: the enemy within

America's cultural roots

America's cultural mindset

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.