Supporting the argument in Are Comics Dead?, more evidence of what comics can and should do to survive. From the LA Times, 8/28/01:

Supporting the argument in Are Comics Dead?, more evidence of what comics can and should do to survive. From the LA Times, 8/28/01: Supporting the argument in Are Comics Dead?, more evidence of what comics can and should do to survive. From the LA Times, 8/28/01:

Supporting the argument in Are Comics Dead?, more evidence of what comics can and should do to survive. From the LA Times, 8/28/01:

Undressed for Success?

For a hip, new generation, the familiar costume of red cape and tights no longer makes the Superman.

By GEOFF BOUCHER, TIMES STAFF WRITER

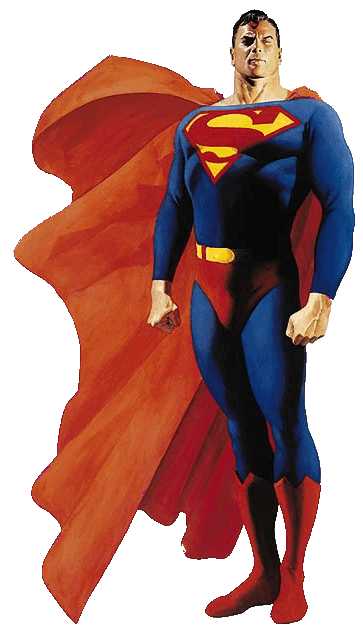

Superman doesn't need that phone booth anymore. For 63 years, the most famous superhero of them all has flown through every pop culture medium wearing his blue tights and red cape, a costume that is instantly recognizable from India to Indiana, by ages 8 to 80. As touchstone, the suit has been as indestructible as the hero himself—until now.

A new WB network series called "Smallville" debuts this season, and, for the first time in any medium, it will chronicle the ongoing exploits of the hero sans costume. The reason? The show's creators say today's teens may be willing to believe a man could leap tall buildings in a single bound, but they're far too hip and media-jaded to accept that he would choose to do so in long johns. "The kids now can't get past that cape," says Miles Millar, one of the show's writers and executive producers. "It is the most recognizable element, yes, but it is also the thing that makes it cheesy." This is more than one hero's fashion crisis. The "tights problem" speaks to the gradual change in the very nature of the American superhero from a square-jawed, all-American crusader that wraps himself, almost literally, in a flag to today's conflicted, gritty avengers who look outfitted by Versace. The old heroes aren't the only ones looking creaky—their primordial home, the American comic book, is an eroding business that has gone from a staple of the youth economy to a minor league that offers up its best creations to other mediums. Today's most popular superheroes flash not across newsprint pages, but across shimmering screens in digital glory.

The new heroes are leather-clad, ironic and darkly dangerous heroes found in "The Matrix," "Buffy the Vampire Slayer," "Tomb Raider" and "X-Men," all big successes as films, video games, television shows, comic books or a combination of all.

"There is something going on here," says Michael Uslan, executive producer of the "Batman" film franchise for Warner Bros. and a longtime comic-book creator and historian. "For today's generation, unlike the baby boomers, the most important thing about the hero is what's going on inside them, their motivations and characterization. It's not as simple as capes and being faster than a speeding bullet."

And against today's backdrop, the bright primary colors of the Superman costume and legend seem as out of place as John Wayne at a rave.

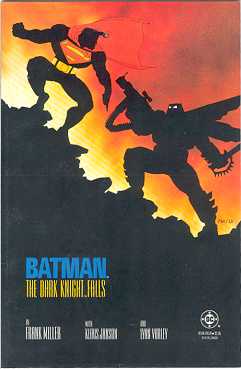

He even gets grief from his old friends about it. "You always say yes to anyone with a badge or a flag," Batman snaps at Superman as the two old friends battle in "The Dark Knight Returns," the celebrated 1986 comic-book series, which, more than any other work, ushered in the current vogue of serious, psychological heroes. "You're a joke," Batman says a few pages later before his elaborate machinations send Superman near death. It's a fitting metaphor for recent history; the haunted Batman is a far better fit in the current fashion, explaining in part why his film franchise has raked in millions in recent years while a long-planned Superman project has languished.

The Hollywood trades reported recently that Superman may indeed be hitting the big screen again, but the new project now circulating through the system would be a buddy movie teaming him up with—big surprise—the far more palatable Batman. How much you want to bet that Superman will be played as the super-strong square?

Still, packing away what may be the most famous piece of clothing in pop culture is, for comic-book lovers and pop culture traditionalists, as jolting as the installation of lights in Wrigley Field or Bob Dylan's decision to go electric.

"It is courageous," says Stan Lee, the comic-book impresario who co-created Spider-Man, the Hulk and scores of other characters for Marvel Comics, the longtime rival to Superman's publisher, DC Comics. "Superhero stories are the fairy tales of today and they require a lot of color and sense of fantasy, and that's what the costumes have done.... But now, with things like 'The X-Files,' you have the same fantastic worlds but with a realistic look."

Lee pauses for a moment and adds a telling afterthought. "You know, I'm working on some new television projects now, too, and none have costumed heroes either."

In a quirky crossover in the comic-book industry, Lee is also working on a Superman comic book for the first time—his one-off take on the character hits stores this month with a blond version of the character with an entirely different history and costume. That's part of an effort by DC Comics in recent years to present the old warhorse hero in new ways: They killed him for a while, married him off to longtime flame Lois Lane and presented him for a few months in a different, cosmic-looking costume. Still, those alterations smacked of stunts, and the comics always returned to the familiar mythos and cape.

More Recognizable Than Santa Claus' Red Suit

To Bradford C. Wright, the author of "Comic Book America," the Superman tights have become an institution that flies far beyond comic books and adaptations. "Nothing really compares to that costume," Wright said. "Not Santa Claus' red suit or the Elvis jumpsuit—nothing is as recognizable."

For generations, Superman has been bulletproof as an entertainment icon. Movie and radio serials, film, television, Broadway shows, novels, newspaper comic strips, the Internet—everywhere. He was a guest star on "I Love Lucy" (in the person of actor George Reeves, the most famous televised Man of Steel) and a staple reference on "Seinfeld," thanks to Jerry Seinfeld's real-life love of the character.

The costume has been so powerful an image, the actors that wore it on screen often found it impossible to peel off. Kirk Alyn, who portrayed Superman from just 1948 to 1950 in movie serials, said years later that the role "ruined my acting career and I've been bitter for many years about the whole thing." Reeves, the definitive hero for a generation as the 1950s Superman on television, so reviled the suffocating aspects of the role that he would burn his costume at the end of each season—except for the logo, which he cut out and gave away. Two years after the show ended, Reeves was found shot to death in what was ruled a suicide.

The logo that tormented Reeves is now tattooed on thousands of people, among them Lakers star Shaquille O'Neal, rocker Jon Bon Jovi and 'N Sync member Joey Fatone. The logo is also a phenomenally popular T-shirt with very young children and their older siblings who wear it for kitsch value or as a shorthand statement of their own bravado. They don't, it should be noted, generally wear capes.

Still, O'Neal said last week the concept of a Superman show without the familiar costume sounded like a half-court heave. "I'm going to have to see how they shot it, with all the special effects and everything," he said. "My question is: How can people determine who Superman is [without a costume]? That's crazy."

It's an understandable point of view. Superman and his costume have flown over the Macy's Thanksgiving Day parade, been painted by Andy Warhol and graced the cover of Time magazine. He has been referenced in songs by R.E.M., the Kinks, Laurie Anderson, Jim Croce and, most recently of note, in the major 2000 hit song "Kryptonite" by Three Doors Down. The hero is still oft-cited, too, by world leaders, celebrities, authors and anyone else in search of a metaphor for America, strength or bizarre fashion choices. "I am a fan," playwright David Mamet once said of Superman, "of anybody who can make his living in his underwear."

Ah, yes, but that's the very problem now.

Certainly, thousands of very young children still don Superman Halloween costumes and pajamas, but they seem to shed the hero behind far quicker than past generations. During World War II, for instance, 1 in 4 periodicals shipped to troops overseas were comic books and, after the war, some titles swelled past 1 million in monthly circulation—a pair of numbers that suggest that teens and young adults of that era didn't mind capes.

Heroes in Upcoming Films Won't Wear Tights

Comic books have become a favored font of Hollywood concepts in recent years, in part because of some big pay-offs (such as "X-Men," "Blade" and "Men in Black"), and also because the current special effects renaissance makes it possible to create, as Uslan puts it, "a seamless, believable and vivid adaptation of these fantastic comic book worlds." Still, most film adaptations of comic books now being discussed or made—including the Hulk, Deathlock, Iron Fist, Ghost Rider and the "From Hell" graphic novel—will not have a hero in tights. The huge exception to that tack is one of the biggest movies planned for 2002, "Spider-Man." Director Sam Raimi, known for an eclectic range of films that include "A Simple Plan," "Darkman" and "For Love of the Game," is now working on the film that presents actor Tobey Maquire in the wall-crawling hero's famous red and blue tights as he shimmies up skyscrapers. Raimi, a lifelong fan of comics, says the film will have to present a world that makes it seem plausible that a young man bitten by a radioactive spider would gain fantastic powers and fight crime—and choose to wear tights. Oddly, it may be easier to accept the former rather than the latter.

The challenge facing Raimi fascinates the makers of "Smallville," but they have no interest in testing the issue themselves, especially with the limited special effects budget and more-mundane video visuals of television. "Smallville," which premieres Oct. 16, cleverly tweaks the Superman legend to make the hero more interesting to today's young adults. The show takes the reality-grounded supernatural elements of the "X-Files" and presents them with the slick production style, pop soundtrack and heartfelt teen pathos of "Dawson's Creek."

This "Krypton Creek" of sorts starts off, as the Superman legend so often does, with a spaceship ferrying an infant, the last survivor of the planet Krypton, to a small Kansas town. But while the first Superman tale ever, Action Comics No. 1 in June 1938, had that baby grow into a costumed mystery man by page two, "Smallville" limits its story line to young Clark Kent's high school years in the title township, which has a reputation for strange phenomena. (The eerie doings, it turns out, arrived with the radiation left by the meteorite shower that accompanied the rocket ship.) Most of his powers manifest with puberty, complicating his teen struggles with unrequited love, guilt, general high school angst and the alienation of being, well, you know, an alien.

The pilot was written and developed by Alfred Gough and Miles Millar, a pair of 31-year-olds who came to the project after the success of their "Shanghai Noon" screenplay. The duo, who also take executive producer credits on "Smallville," shrug when asked if they grew up in the thrall of the Superman mythos. "I liked the Richard Donner movie a lot," Gough says. That tepid allegiance compelled the pair to agree to the "Smallville" project only if the familiar legend could be mined selectively. So Clark Kent will never be called Superman, he won't fly, he won't own a cape, and he counts Lex Luthor among his friends. "Our main caveats," Gough says, "were no tights, no flights."

They know they will be painted as villains by some in comic-book fandom, a community known for Trekkie-like devotion to its beloved characters and a general indignation toward outsiders who monkey with the details. "I'm sure there are going to be a core group of Superman fans out there that have certain expectations that won't be met," Millar says. "But so far they seem to be embracing it. The mythology has changed through the years, it wasn't set in stone in the 1930s. It hasn't been set in stone. It's OK see if new things can fly."

More on the subject

Superheroes Spin Web Around Red-Blue Divide

Related links

Why write about superheroes?

The future of comics

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.