"An unenlightened race of men"

But see how they [the inhabitants of New Spain and Mexico] deceive themselves, and how much I dissent from such an opinion, seeing, on the contrary, in these very institutions a proof of the crudity, the barbarity, and the natural slavery of these people; for having houses and some rational way of life and some sort of commerce is a thing which the necessities of nature itself induce, and only serves to prove that they are not bears of monkeys and are not totally lacking in reason. But on the other hand, they have established their nation in such a way that no one possesses anything individually, neither a house nor a field, which he can leave to his heirs in his will, for everything belongs to their masters whom, with improper nomenclature, they call kings, and by whose whims they live, more than by their own, ready to do the bidding and desire of these rulers and possessing no liberty. And the fulfillment of all this, not under the pressure of arms but in voluntary and spontaneous way, is a definite sign of the servile and base soul of there barbarians....Therefore, if you wish to reduce them, I do not say to our domination, but to a servitude a little less harsh, it will not be difficult for them to change their masters, and instead of the one they had, who were barbarous and impious and inhuman, to accept the Christians, cultivators of human virtues and the true faith....

Juan Gines de Sepulvèda, The Second Democrates, 1547

Compare then those blessings enjoyed by Spaniards of prudence, genius, magnanimity, temperance, humanity, and religion with those of the homunculi in whom you will scarcely find even vestiges of humanity, who not only possess no science but who also lack letters and preserve no monument of their history except certain vague and obscure reminiscences of some things in certain paintings. Neither do they have written laws, but barbaric institutions and customs. They do not even have private property.

Juan Gines de Sepulvèda, 1550

The redskinned Indians are naturally lazy and vicious, melancholic, cowardly, and in general a lying, shiftless, people. Their marriages are not a sacrament but a sacrilege. They are idolatrous, libidinous, and commit sodomy. Their chief desire is to eat, drink, worship heathen idols, and commit bestial obscenities. What could one expect from a people whose skulls are so thick and hard that the Spaniards had to take care in fighting not to strike on the head lest their swords be blunted?

Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdes, 16th century

But Englishmen also entertained another more positive version of the New World native. Richard Hakluyt, the great propagandist for English colonization, described the Indians in 1585 as "simple and rude in manners, and destitute of the knowledge of God or any good laws, yet of nature gentle and tractable, and most apt to receive the Christian Religion, and to subject themselves to some good government." Many other reports spoke of the native in similarly optimistic terms.

Gary B. Nash, Red, White, and Black: The Origins of Racism in Colonial America

Edward Waterhouse, writing after the Massacre of 1622, could only describe the Indians as "by nature sloath-full and idle, vitious, melancholy, slovenly, of bad conditions, lyers, of small memory, of no constancy or trust…by nature of all people the most lying and most inconstant in the world, sottish and sodaine, never looking what dangers may happen afterwards, lesse capable then children of sixe or seaven years old, and less apt and ingenious .... Samuel Purchas, writing in 1625 of the Virginia Indians, described them as "bad people, having little of Humanitie but shape, ignorant of Civilitie, of Arts, of Religion; more brutish then [sic] the beasts they hunt, more wild and unmanly then [sic] that unmanned wild Countrey which they range rather than inhabite; captivated also to Satans tyranny in foolish pieties, mad impieties, wicked idleness, busie and bloudy wickednesse ....

Gary B. Nash, Red, White, and Black: The Origins of Racism in Colonial America

Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor'd mind

Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind;

His soul proud Science never taught to stray

Far as the solar walk or milky way.

Alexander Pope, Epistle i, Line 99, An Essay on Man, 1733-1734

A system corresponding with the mild principles of religion and philanthropy toward an unenlightened race of men, whose happiness materially depends on the conduct of the United States, would be as honorable to the national character as conformable to the dictates of sound policy.

It is universally admitted that the earth was designed for improvement and tillage, and the right of civilized communities to enter upon and appropriate to such purposes, any lands that may be occasionally occupied or claimed as hunting grounds by uncultivated savages, is sanctioned by the laws of nature and of nations.

Noah Noble, governor of Alabama, 1832

No State can achieve proper culture, civilization, and progress...as long as Indians are permitted to remain.

Martin Van Buren, 1837

As I passed over those magnificent bottoms of the Kansas which form the reservations of the Delaware, Potawatomies, etc., constituting the very best cornlands on earth, and saw their owners sitting around the doors of their lodges at the height of the planting season and in as good, bright planting weather as sun and soil ever made, I could not help saying, "These people must die out—there is no help for them. God has given this earth to those who will subdue and cultivate it, and it is vain to struggle against His righteous decree."

Horace Greeley, Letter 13: Lo! the Poor Indian!, An Overland Journey, from New York to San Francisco, in the Summer of 1859, 1860

[E]very redskin must be killed from off the face of the plains before we can be free from their molestations. They are of no earthly good and the sooner they are swept from the land the better for civilization....I do not think they can be turned and made good law abiding citizens any more than coyotes can be used for shepherd dogs.

Major John Vance Lauderdale, US Army surgeon, 1866

The legal status of the uncivilized Indians should be that of wards of the government; the duty of the latter being to protect them, to educate them in industry, the arts of civilization, and the principles of Christianity.

1869 Board of Indian Commissioners Annual Report 10

The establishment of Christian missions should be encouraged, and their schools fostered....The religion of our blessed Savior is believed to be the most effective agent for the civilization of any people.

1869 Board of Indian Commissioners Annual Report 10

On the morning of the sixteenth day out from St. Joseph we arrived at the entrance of Rocky Canyon, two hundred and fifty miles from Salt Lake. It was along in this wild country somewhere, and far from any habitation of white men, except the stage stations, that we came across the wretchedest type of mankind I have ever seen, up to this writing. I refer to the Goshoot Indians. From what we could see and all we could learn, they are very considerably inferior to even the despised Digger Indians of California; inferior to all races of savages on our continent; inferior to even the Tierra del Fuegans; inferior to the Hottentots, and actually inferior in some respects to the Kytches of Africa. Indeed, I have been obliged to look the bulky volumes of Wood's Uncivilized Races of Men clear through in order to find a savage tribe degraded enough to take rank with the Goshoots.

Mark Twain, Roughing It, 1872

The "peace policy" proposed to place the Indians upon reservations as rapidly as possible, where they can be provided for in such manner as the dictates of humanity and Christian civilization require. Being thus placed upon reservations they will be removed from such contiguity to our frontier settlements as otherwise will lead, necessarily, to frequent outrages, wrongs, and disturbances of our public peace. On these reservations they can be taught, as fast as possible, the arts of agriculture and such pursuits as are incident to civilization, through the aid of the Christian organizations of the country now engaged in this work, acting in harmony with the Federal Government. Their intellectual, moral, and religious culture can be prosecuted, and thus it is hoped that humanity and kindness may take the place of barbarity and cruelty.

Columbus Delano, Secretary of the Interior, letter, April 15, 1873

Another Sherman biographer, John F. Marszalek, points out in Sherman: A Soldier's Passion for Order, that "Sherman viewed Indians as he viewed recalcitrant Southerners during the war and newly freed people after the war: resisters to the legitimate forces of an orderly society," by which he meant the central government. Moreover, writes Marszalek, Sherman's philosophy was that "since the inferior Indians refused to step aside so superior American culture could create success and progress, they had to be driven out of the way as the Confederates had been driven back into the Union."

.

.

.

Sherman and General Phillip Sheridan were associated with the statement that "the only good Indian is a dead Indian." The problem with the Indians, Sherman said, was that "they did not make allowance for the rapid growth of the white race" (Marszalek, p. 390). And, "both races cannot use this country in common" (Fellman, p. 263).

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, How Lincoln's Army 'Liberated' the Indians

The invention or practice of the art of pottery, all things considered, is probably the most effective and conclusive test that, can he selected to fix a boundary line, necessarily arbitrary, between savagery and barbarism. The distinctness of the two conditions has long been recognized, but no criterion of progress out of the former into the latter has hitherto been brought forward. All such tribes, then, as never attained to the art of pottery will be classed as savages, and those possessing this art, but who never attained a phonetic alphabet and the use of writing will be classed as barbarians.

Lewis H. Morgan, Ancient Society, Or, Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization, 1877

Periods...Conditions

I. Lower Status of Savagery, From the Infancy of the Human Race to the commencement of the next Period.

II. Middle Status of Savagery, From the acquisition of a fish subsistence and a knowledge of the use of fire to etc.

III. Upper Status of Savagery, From the Invention of the Bow and Arrow, to etc.

IV. Lower Status of Barbarism, From the Invention of the Art of Pottery, to etc.

V. Middle Status of Barbarism, From the Domestication of animals on the Eastern hemisphere, and in the Western from the cultivation of maize and plants by Irrigation, with the use of adobe-brick and stone, to etc.

VI. Upper Status of Barbarism, From the Invention of the process of Smelting Iron Ore, with the use of iron tools, to etc.

VII. Status of Civilization, From the Invention of a Phonetic Alphabet, with the use of writing, to the present time.

Lewis H. Morgan, Ancient Society, Or, Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization, 1877

The great evils in the way of their ultimate civilization lie in these dances. The dark superstitions and unhallowed rites of a heathenish as gross as that of India or Central Africa still infects them with its insidious poison, which, unless replaced by Christian civilization, must sap their very life blood.

J.H. Fleming, Moquis Pueblo Agency, Aug. 31, 1882, quoted in the 1882 Commissioner of Indian Affairs Annual Report 5

[Medicine men] resort to various artifices and devices to keep the people under their influence, and are especially active in preventing the attendance of the children at the public schools, using their conjurers' arts to prevent people from abandoning their heathenish rites and customs.

Henry Teller, Secretary of the Interior, 1883 Secretary of the Interior Annual Report

If it is the purpose of the Government to civilize the Indians, they must be compelled to desist from the savage and barbarous practices that are calculated to continue them in savagery, no matter what exterior influences are brought to bear on them.

Henry Teller, Secretary of the Interior, 1883 Secretary of the Interior Annual Report

During the past century a good deal of sentimental nonsense has been talked about our taking the Indians' land. Now, I do not mean to say for a moment that gross wrong has not been done the Indians, both by government and individuals, again and again. The government makes promises impossible to perform, and then fails to do even what it might toward their fulfilment; and where brutal and reckless frontiersmen are brought into contact with a set of treacherous, revengeful, and fiendishly cruel savages a long series of outrages by both sides is sure to follow. But as regards taking the land, at least from the western Indians, the simple truth is that the latter never had any real ownership in it at all. Where the game was plenty, there they hunted; they followed it when it moved away to new hunting-grounds, unless they were prevented by stronger rivals; and to most of the land on which we found them they had no stronger claim than that of having a few years previously butchered the original occupants. When my cattle came to the Little Missouri the region was only inhabited by a score or so of white hunters; their title to it was quite as good as that of most Indian tribes to the lands they claim; yet nobody dreamed of saying that these hunters owned the country. Each could eventually have kept his own claim of 160 acres, and no more. The Indians should be treated in just the same way that we treat the white settlers. Give each his little claim; if, as would generally happen, he declined this, why then let him share the fate of the thousands of white hunters and trappers who have lived on the game that the settlement of the country has exterminated, and let him, like these whites, who will not work, perish from the face of the earth which he cumbers.

The doctrine seems merciless, and so it is; but it is just and rational for all that. It does not do to be merciful to a few, at the cost of justice to the many. The cattle-men at least keep herds and build houses on the land; yet I would not for a moment debar settlers from the right of entry to the cattle country, though their coming in means in the end the destruction of us and our industry.

Theodore Roosevelt, Chapter I: Ranching in the Bad Lands, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, 1885

[Dances recount] in speech and song...the horses stolen and scalps taken from enemies in wars in the distant past, all of which are brought vividly before the minds of the youth and middle aged, producing an influence which leads them to believe that such a life is more to be preferred than a life of labor.

J.F. Kinney, Yankton Agency, Aug. 23, 1886, quoted in the 1886 Commission on Indian Affairs Annual Report

These ways of the Indian...comprise to us a monstrous but to them a very sacred religion.

E.C. Osborne, Ponca, Pawnee, Otoe and Oakland Agency, Sept. 10, 1886, quoted in the 1886 Commissioner of Indian Affairs Annual Report 136

[Education] cuts the cord that binds [Indians] to a Pagan life, places the Bible in their hands, substitutes the true God for the false one, Christianity in place of idolatry...cleanliness in place of filth, industry in place of idleness.

1887 Superintendent of Indian Education Annual Report 131

The policy of the government is to aid these mission schools in the great Christian enterprise of rescuing from lives of barbarism and savagery these Indian children, and conferring upon them the benefits of an educated civilization.

In re Can-ah-couqua, 29 F. 687 (D. Alaska 1887)

The most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages, though it is apt to be also the most terrible and inhuman. The rude, fierce settler who drives the savage from the land lays all civilized mankind under a debt to him. American and Indian, Boer and Zulu, Cossack and Tartar, New Zealander and Maori,—in each case the victor, horrible though many of his deeds are, has laid deep the foundations for the future greatness of a mighty people. The consequences of struggles for territory between civilized nations seem small by comparison. Looked at from the standpoint of the ages, it is of little moment whether Lorraine is part of Germany or of France, whether the northern Adriatic cities pay homage to Austrian Kaiser or Italian King; but it is of incalculable importance that America, Australia, and Siberia should pass out of the hands of their red, black, and yellow aboriginal owners, and become the heritage of the dominant world races.

Theodore Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, Volume Three: The Founding of the Trans-Alleghany Commonwealths, 1784-1790, 1894

While we had a frontier the chief feature of frontier life was the endless war between the settlers and the red men. Sometimes the immediate occasion for the war was to be found in the conduct of the whites and sometimes in that of the reds, but the ultimate cause was simply that we were in contact with a country held by savages or half-savages. Where we abut on Canada there is no danger of war, nor is there any danger where we abut on the well-settled regions of Mexico. But elsewhere war had to continue until we expanded over the country. Then it was succeeded at once by a peace which has remained unbroken to the present day. In North America, as elsewhere throughout the entire world, the expansion of a civilized nation has invariably meant the growth of the area in which peace is normal throughout the world.

Theodore Roosevelt, Expansion and Peace, The Independent, December 21, 1899

[I]t was not that long hair, paint, blankets, etc., are objectionable in themselves—that is largely a question of taste—but that they are a badge of servitude to savage ways and traditions which are effectual barriers to the uplifting of the race.

W.A. Jones, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to E.A. Hitchcock, Secretary of the Interior, printed in the 1902 Commissioner of Indian Affairs Annual Report

Indian dances and so-called Indian feasts should be prohibited. In many cases these dances and feasts are simply subterfuge to cover degrading acts and to disguise immoral purposes.

W.A. Jones, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to E.A. Hitchcock, Secretary of the Interior, printed in the 1902 Commissioner of Indian Affairs Annual Report

The "sun dance", and all other similar dances and so-called religious ceremonies, shall be considered "Indian offenses," and any Indian found guilty of being a participant in any one or more of these offenses shall...be punished by withholding from him his rations for a period of not exceeding ten days; and if found guilty of any subsequent offense under this rule, shall be punished by withholding his rations for a period not less than fifteen days nor more than thirty days, or by incarceration in the agency prison for a period not exceeding thirty days.

Secretary of the Interior, Regulations of the Indian Office, effective Apr. 1, 1904

[T]he barbarism of the whole celebration [Hopi Snake Dance] exceeded everything that we thought possible on this continent.

Indian Rights Association report, reprinted in Lawrence Kelly's The Assault on Assimilation: John Collier and the Origins of Indian Policy Reform

It was perhaps fortunate for the future of America that the Indians of the North rejected civilization. Had they accepted it the whites and Indians might have intermarried to some extent as they did in Mexico. That would have given us a population made up in a measure of shiftless half-breeds.

History book published shortly after 1900, quoted in Custer Died for Your Sins by Vine Deloria Jr.

As Indians are only grown-up children, they must be taught just as children are taught, as much as may be of the knowledge which the white man absorbs unconsciously from his early association and his reading. The civilization of the Indian has been slow, chiefly because his mental attitude has not been understood by the men employed in the field service of the Indian Bureau. It has been slow very largely be cause we have not seen to it that the men chosen for this service were competent to teach the Indian how to live in our way and to convey to the savage man of Stone Age development the intelligence of civilized man.

George Bird Grinnell, "Chapter I: The North American Indians," The Indians of To-Day, 1911

The Indian has the mind of a child in the body of an adult. The struggle for existence weeded out the weak and the sickly, the slow and the stupid, and created a race physically perfect, and mentally fitted to cope with the conditions which they were forced to meet, so long as they were left to them selves. When, however, they encountered the white race, equipped with the mental training and accumulated wisdom of some thousands of years, they were compelled to face a new set of conditions. The balance of nature, which had been well enough maintained so long as nature ruled, was rudely disturbed when civilized man appeared on the scene. His improved tools and implements gave him an enormous advantage over the Indian, but this advantage counted for little in comparison with the mental superiority of the civilized man over the savage.

George Bird Grinnell, "Chapter II: Indian Character," The Indians of To-Day, 1911

The people of the Pueblos, although sedentary rather than nomadic in their inclinations and disposed to peace and industry, are nevertheless Indians in race, customs, and domestic government, always living in separate and isolated communities, adhering to primitive modes of life, largely influenced by superstition and fetishism, and chiefly governed according to the crude customs inherited from their ancestors. They are essentially a simple, uninformed, and inferior people.

United States v. Sandoval, 231 U.S. 28, 1913

The school's objective was to teach order and discipline, to remake the students into the image of the white farmer and to strip away their culture and religious practices.

"One of the goals of the non-reservation boarding schools was, in addition to the assimilation of children and youth, to have them, in turn, influence their families back on the reservation. They would learn the ways of 'civilization' at school and, theoretically, impart these ways to their parents, thereby killing two birds with one stone, so to speak," said archeologist and historian Jean Keller, author of the recently published book "Empty Beds — Indian Student Health at Sherman Institute, 1902-1922."

Cecilia Rasmussen, "Institute Tried to Drum 'Civilization' Into Indian Youth," Los Angeles Times, 2/23/03

All of these acts were and are made possible by one fundamental rationalization: that our society represents the ultimate expression of evolution, its final flowering. It is this attitude, and its corresponding belief that native societies represent an earlier, lower form on the evolutionary ladder, upon which we occupy the highest rung, that seem to unify all modern political perspectives: Right, Left, Capitalist, and Marxist.

Jerry Mander, In the Absence of the Sacred, 1991

Socialism at work....

The last bastion of socialism in North America....

A failed experiment in socialism....

Descriptions of Indian reservations, James Watt, Secretary of the Interior under Ronald Reagan, 1980s

Let me tell you just a little something about the American Indian in our land. We have provided millions of acres of land for what are called preservations—or reservations, I should say. They, from the beginning, announced that they wanted to maintain their way of life, as they had always lived there in the desert and the plains and so forth. And we set up these reservations so they could, and have a Bureau of Indian Affairs to help take care of them. At the same time, we provide education for them—schools on the reservations. And they're free also to leave the reservations and be American citizens among the rest of us, and many do. Some still prefer, however, that way—that early way of life. And we've done everything we can to meet their demands as to how they want to live. Maybe we made a mistake. Maybe we should not have humored them in that wanting to stay in that kind of primitive lifestyle. Maybe we should have said, no, come join us; be citizens along with the rest of us.

Ronald Reagan, Moscow State University, 5/31/88

They hang onto remnants of their religion and superstitions that may have been useful to savages 500 years ago, but which are meaningless in 1992.

Andy Rooney, Indians Seek a Role in Modern U.S., 1992

The Native American culture is a culture of hopelessness, godlessness, joblessness and lawlessness, a mongrelized people living on the outskirts of Western civilization.

Mike Whalen, assistant attorney general for South Dakota, Sept. 1992 (?)

Columbus saved the Indians from themselves.

Rush Limbaugh, radio show, c. 2000

Once a woman went so far as to inform me that if it were not for Christopher Columbus, today's residents of the Western Hemisphere would be absent of paper, computers, airplanes, telephones and literature because Columbus "brought civilization to people who lived like cavemen."

Terri Jean, "Should We Kill Off Christopher Columbus?" 10/29/01

Our leaders, meanwhile, keep telling themselves, in the face of all evidence, that the ancient traditions of illiterate hunter-gatherers can somehow be welded to a modern economy; as if the cruel march of history could be defeated by an act of collective good will.

Jonathan Kay, The Case for Assimilation, 12/8/01

Canada's natives, itinerant foragers and hunters two centuries ago, are now sedentary welfare-collectors. Their relationship with the land has eroded greatly because they no longer depend on it for food. Thanks to television, they are also abandoning native languages in favour of English and French, and have largely shed their animistic faiths.

Jonathan Kay, A Better Life for Natives—a Whiter One, Too, 6/19/02

The reservation is a magnet for mooches because federal time limits on welfare benefits don't apply at Pine Ridge.

Here where cradle-to-grave socialism, the Democrats' fantasy state, is realized, more than half the reservation's adults battle addiction and disease.

Michelle Malkin, The Shambles in South Dakota, 10/23/02

So tractable, so peaceable, are these people that I swear to your Majesties there is not in the world a better nation. They love their neighbors as themselves, and their discourse is ever sweet and gentle, and accompanied with a smile, and though it is true that they are naked, yet their manners are decorous and praiseworthy.

Christopher Columbus, letter to Ferdinand and Isabella, 1493

John Lawson, who traveled extensively among the southeastern tribes in the early eighteenth century, also dwelled on the integrity of native culture and took note of many traits, such as cleanliness, equable temperament, bravery, tribal loyalty, hospitality, and concern for the welfare of the group rather than the individual, that often seemed absent from English society. Like Beverley, Lawson concluded that the Indians of the southern regions were the "freest people from Heats and Passions (which possess the Europeans)." He lamented that contact with the settlers had vitiated what was best in Indian culture. Many other writers who did not covet the Indians' land or were not engaged in the exploitive Indian trade, agreed that the concept of community, which colonial leaders cherished as an ideal but rarely achieved, was best reflected in North America by the natives. As Pearce has noted, "the essential integrity of savage life, for good and bad, became increasingly the main concern of eighteenth-century Americans writing on the Indian."

Gary B. Nash, Red, White, and Black: The Origins of Racism in Colonial America

In most pre Columbus American cultures, the political structure resembled a democratic society. In contrast, Christian Europe was a feudal system with an economic class, controlled by the tyrannic church....

Dave Fisher, "Violent Christian Europe vs. the Americas"

I am convinced that those societies (as the Indians) which live without government enjoy in their general mass an infinitely greater degree of happiness than those who live under European governments. Among the former, public opinion is in the place of law, and restrains morals as powerfully as laws ever did any where. Among the latter, under pretence of governing they have divided their nations into two classes, wolves and sheep.

...It is necessary that we should not lose sight of an important truth which continually receives new confirmations, namely, that the provisions heretofore made with a view to the protection of the Indians from the violences of the lawless part of our frontier inhabitants are insufficient. It is demonstrated that these violences can now be perpetrated with impunity, and it can need no argument to prove that unless the murdering of Indians can be restrained by bringing the murderers to condign punishment, all the exertions of the Government to prevent destructive retaliations by the Indians will prove fruitless and all our present agreeable prospects illusory. The frequent destruction of innocent women and children, who are chiefly the victims of retaliation, must continue to shock humanity, and an enormous expense to drain the Treasury of the Union.

George Washington, Seventh Annual Address, December 8, 1795

[In Agrarian Justice, Thomas Paine] returned once again to the Iroquois, among whom he had learned democracy, when he wrote, "The fact is, that the condition of millions, in every country in Europe, is far worse than if they had been born before civilization began, or had been born among the Indians of North-America at the present day."

Jack Weatherford, Indian Givers

James Axtell analyzed documents of Europeans who fled the tyrannic Christian life and lived with the Indians. He concluded that "whites chose to remain part of the Indian culture because they had"

However, the Christian leaders didn't like the idea that some of their people would favor a heathen life like this. One without the hatred, racism, and malice towards others, even towards those within the same community. Therefore, laws were made to control people with fear if they chose to live a life filled with love. The penalty was, of course, severe for those who sought to leave the evils of Christian settlements. They were hunted down, caught, and faced many different forms of punishment, depending on how religious the Christians felt. They could be flogged, shot, or burned alive.

Dave Fisher, "The Christian Invasion of North America by the English"

Love one another and do not strive for another's undoing. Even as you desire good treatment, so render it.

Handsome Lake (Seneca), after his vision of three angels in ancient Iroquois regalia, 1799, quoted in The Code of Handsome Lake, the Seneca Prophet by Arthur C. Parker, 1913

Our Creator put us on this wide, rich land, and told us we were free to go where the game was, where the soil was good for planting. That was our state of true happiness. We did not have to beg for anything. Our Creator had taught us how to find and make everything we needed, from trees and plants and animals and stone. We lived in bark, and we wore only the skins of animals. Our Creator taught us how to use fire, in living, and in sacred ceremonies. She taught us how to heal with barks and roots, and how to make sweet foods with berries and fruits, with papaws and the water of the maple tree. Our Creator gave us tobacco, and said, Send your prayers up to me on its fragrant smoke. Our Creator taught us how to enjoy loving our mates, and gave us laws to live by, so that we would not bother each other, but help each other. Our Creator sang to us in the wind and the running water, in the bird songs, in children's laughter, and taught us music. And we listened, and our stomachs were never dirty and never troubled us.

Our Creator put us on this wide, rich land, and told us we were free to go where the game was, where the soil was good for planting. That was our state of true happiness. We did not have to beg for anything. Our Creator had taught us how to find and make everything we needed, from trees and plants and animals and stone. We lived in bark, and we wore only the skins of animals. Our Creator taught us how to use fire, in living, and in sacred ceremonies. She taught us how to heal with barks and roots, and how to make sweet foods with berries and fruits, with papaws and the water of the maple tree. Our Creator gave us tobacco, and said, Send your prayers up to me on its fragrant smoke. Our Creator taught us how to enjoy loving our mates, and gave us laws to live by, so that we would not bother each other, but help each other. Our Creator sang to us in the wind and the running water, in the bird songs, in children's laughter, and taught us music. And we listened, and our stomachs were never dirty and never troubled us.

Thus were we created. Thus we lived for a long time, proud and happy. We had never eaten pig meat, nor tasted the poison called whiskey, nor worn wool from sheep, nor struck fire or dug earth with steel, nor cooked in iron, nor hunted and fought with loud guns, nor ever had diseases which soured our blood or rotted our organs. We were pure, so we were strong and happy.

But, beyond the Great Sunrise Water, there lived a people who had iron, and those dirty and unnatural things, who seethed with diseases, who fought to death over the names of their gods! They had so crowded and befouled their own island that they fled from it, because excrement and carrion were up to their knees. They came to our island. Our Singers had warned us that a pale people would come across the Great Water and try to destroy us, but we forgot. We did not know they were evil, so we welcomed them and fed them. We taught them much of what Our Grandmother had taught us, how to hunt, grow corn and tobacco, find good things in the forest. They saw how much room we had, and wanted it. They brought iron and pigs and wool and rum and disease. They came farther and drove us over the mountains. Then when they had filled up and dirtied our old lands by the sea, they looked over the mountains and saw this Middle Ground, and we are old enough to remember when they started rushing into it. We remember our villages on fire every year and the crops slashed every fall and the children hungry every winter. All this you know.

Tenskwatawa (Shawnee), message to his people, c. 1805

Trouble no one about their religion; respect others in their view, and Demand that they respect yours. Love your life, perfect your life, beautify all things in your life. Seek to make your life long and its purpose in the service of your people. Prepare a noble death song for the day when you go over the great divide. Always give a word or a sign of salute when meeting or passing a friend, even a stranger, when in a lonely place. Show respect to all people and bow to none.

Tecumseh (Shawnee), quoted in Shawnee History by Lee Sulzman

In 1832 George Catlin, the painter, went West and spent eight years with the unchanged Indians of the Plains. He lived with them and became conversant with their lives. He has left one of the fullest and best records we have of the Redman. From his books I quote repeatedly. Concerning the Indian's religion, he says:

The North American Indian is everywhere, in his native state, a highly moral and religious being, endowed by his Maker with an intuitive knowledge of some great Author of his being, and the Universe, in dread of whose displeasure he constantly lives, with the apprehension before him of a future state, where he expects to be rewarded or punished according to the merits he has gained or forfeited in this world.

Morality and virtue I venture to say the civilized world need not undertake to teach them.

I never saw any other people of any color who spend so much of their lives in humbling themselves before and worshipping the Great Spirit. (Catlin's "N. A. Indian," Vol. II., p. 243.)

We have been told of late years that there is no evidence that any tribe of Indians ever believed in one overruling power; yet, in the early part of the seventeenth century, Jesuits and Puritans alike testified that tribes which they had met, believed in a god, and it is certain that, at the present time, many tribes worship a Supreme Being who is the Ruler of the Universe. (Grinnell's Story of the Indian, 1902, p. 214.)

Love and adore the Good Spirit who made us all; who supplies our hunting-grounds, and keeps us alive. (Teachings of Tshut-che-nau, Chief of the Kansas. J. D. Hunter's Captivity Among the American Indians, 1798-1816, p. 21).

Ernest Thompson Seton, "Chapter II: The Spartans of the West," The Book of Woodcraft, 1912

I love a people that have always made me welcome to the very best that they had.

I love a people who are honest without laws, who have no jails and no poorhouses.

I love a people who keep the commandments without ever having read or heard them preached from the pulpit.

I love a people who never swear or take the name of God in vain.

I love a people "who love their neighbors as they love themselves."

I love a people who worship God without a Bible, for I believe that God loves them also.

I love a people whose religion is all the same, and who are free from religious animosities.

I love a people who have never raised a hand against me, or stolen my property, when there was no law to punish either.

I love and don't fear mankind where God has made and left them, for they are his children.

I love the people who have never fought a battle with the white man, except on their own ground.

I love a people who live and keep what is their own without lock and keys.

I love a people who do the best they can.

And oh how I love a people who don't live for the love of money.

George Catlin's Creed about American Indians

[Malcomson] quotes Lincoln, in his first meeting with Indian leaders, as explaining some of the differences between the white and Indian races: "Although we are now engaged in a great war between one another, we are not, as a race, so much disposed to fight and kill one another as our red brethren." Unfortunately, there appears to be no record, at least in Malcomson's book, as to the response that the "red brethren" made to such an outrageous statement. But Malcomson analyzes Lincoln's racial madness: "One might have thought that the carnage of a civil war between white people, widely understood as such at the time, would have undermined the belief in white civilization as superior, not to mention more peaceful—perhaps even have undermined the belief in whiteness itself. White people were killing each other all around Lincoln; he was himself directing much of the killing; and so his seemingly mad assertion of the white race's comparative amiability must have answered a deep need to take an observable, unattractive feature of white behavior and attribute it to another race. If that race were removed from the nation, then would not the unwanted behavior cease as well? In which case the white American race could advance to prosperity and reach that destiny uniquely its own."

Erin Miller, review of Scott Malcomson's One Drop of Blood: The American Misadventure of Race

Col. John Gibbon knew the Nez Perce way of life was destined to be washed away in a tidal wave of white civilization.

He understood that he would have to ride the crest of the wave.

But Gibbon believed the nation's Indian policy was a "foul plot," and went to the Big Hole with his eyes wide open.

"How would we feel, how would we act if our country were overrun and wrested from us by another race?" he asked many years later in one of the numerous articles he wrote. "If our lands were bought with promises to pay which were never fulfilled? If certain other portions of land were guaranteed to us by solemn treaty and these treaties were recklessly violated as soon as precious metals were found upon the land or for any other reason the other race wanted it?"

Lorna Thackeray, Career Soldier Hated 'Disgrace' of U.S. Policy, Billings Gazette, 8/12/02

One of its strongest supports in so doing is the wide-spread sentiment among the people of dislike to the Indian, of impatience with his presence as a "barrier to civilization" and distrust of it as a possible danger. The old tales of the frontier life, with its horrors of Indian warfare, have gradually, by two or three generations' telling, produced in the average mind something like an hereditary instinct of questioning and unreasoning aversion which it is almost impossible to dislodge or soften....

Helen Hunt Jackson, A Century of Dishonor, 1881

We have been guilty of only one sin—we have had possessions that the white man coveted.

Eagle Wing (Sioux), Ploughed Under, the Story of an Indian Chief Told by Himself, 1881

We are all poor because we are all honest.

Red Dog (Oglala Sioux), quoted in Native American Wisdom, late 19th century

You must not hurt anybody or do harm to anyone. You must not fight. Do right always. It will give you satisfaction in life.

Wovoka (Pauite), quoted by James Mooney in "The Ghost-dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890," 14th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Part 2, 1896

I went up to heaven and saw God and all the people who had died a long time ago. God told me to come back and tell my people they must be good and love one another, and not fight, or steal, or lie.

Wovoka (Paiute), c. 1890

It is a commentary on our boasted Christian civilization that although there were two or three salaried missionaries at the agency [during the Wounded Knee Massacre] not one went out to say a prayer over the poor mangled bodies of these victims of war.

James Mooney, "The Ghost-dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890," 1896

[Bill Reid] speaks of the early people, claiming no special status for their humanity among that of other early cultures, but giving it a focus too often neglected: "A small population which over the centuries has learned to live in the same harmony with its environment as other living creatures who shared it, developing skills and techniques sufficient to cope adequately, but little more. [They created] a number of complex social systems with their attendant supporting myths and rituals. These in turn [were] supported by varying degrees of artistic expression—graphic, sculptural, musical, theatrical, poetic. Each intricate cultural structure [was] firmly held in place by a completely formed dense framework of language." He does not present a romantic picture of that past, recognizing its physical harshness and precariousness, its rigidly hierarchical society with its slavery component, its constant intertribal conflicts, but still he proposes that "tribal societies in general, and the Northwest Coast version in particular, probably accommodated the individual better than any system that has succeeded it." As he articulates it:

No one except slaves, and there is some evidence to show that even they participated to some extent, was excluded from the diverse physical activities of the community....Everyone had a hand in the harvesting and preserving of food, while the best hunters and fishermen, and probably the most skilled observers and preparers of food, had added status in the communities. And after these seasonal subsistence activities which seemed to have been considered easy, almost holiday time for the people, like a prolonged picnic, came the serious activities. It meant everyone was not only encouraged to display his abilities, but required to do so. It would seem that all men practised all the men's trades and arts—boatbuilding, carpentry, tool-, weapon-, utensil-, vessel-making, and so on, as well as painting and carving ceremonial objects, as all the women were preparers of food, weavers, basket-makers and so on, and all were singers and dancers, actors in the ritual drams which were such a part of the winter ceremonies. Of course, all were not equally skilled. But those who excelled were apparently recognized and rewarded and everyone with a special talent—the great painters, sculptors, weavers, bards—was cherished by the group. Access to these skills was denied no one—every child from his first conscious moment was in intimate contact with the most highly skilled adults in the community, if for no other reason than that he or she was in intimate contact with every individual in the community. With no forced training, the young effortlessly learned all the wisdom of the group, the natural environment, how to exploit and live with it, th nature of the material available from it, the complexities of the social environment, the genealogies of the great families, the myths of their origins, the use of tools needed to give visible and oral reality to this wealthy symbolism including the greatest tools of all—the rich complex languages of the coast....So every child grew up with as complete a knowledge of his universe and how to cope with it as he was capable of absorbing. He had the highly developed powers of observation which gave him a better than average chance to find his way in this world and wrest from it an abundant livelihood. He learned all the complexities of his society and what his place was in it. He had a body of myths and history embodied in the genealogies of his people, which provided him with guideposts and reference points to help determine the course of his life. And he had a language of sufficient vocabulary and structure to communicate to the rest of his group and to himself all the information necessary to survive culturally, to think his way through his problems and so solve them and to exercise his imagination creatively to enrich his life and his community. In other words, he was a human being, a well-realized product of the unique and marvelous process going back thousands of years by which man invented himself, learned to use and make tools, to live together in social groups, to divide labour, to develop unprecedented uses or parts of his amazing unspecialized body, to communicate in various ways, culminating in the greatest result of his genius—his amazing unbelievable, magical, triumphant creation—his language.

His vision of an earlier society in which the shared assumptions of the higher and lower ranking members were bound together in a mutual, workable, productive interdependence is in glaring contrast with the present picture of village life as a moral, spiritual and material wasteland in which popular western culture at its most vacuous has taken over.

Bill Reid (Haida), describing his traditional culture, in the book Bill Reid by Doris Shadbolt

As a child, I understood how to give; I have forgotten that grace since I became civilized. I lived the natural life, whereas I now live the artificial. Any pretty pebble was valuable to me then; every growing tree an object of reverence. Now I worship with the white man before a painted landscape whose value is estimated in dollars! Thus the Indian is reconstructed, as the natural rocks are ground to powder, and made into artificial blocks which may be built into the walls of modern society.

The youth was encouraged to enlist early in the public service, and to develop a wholesome ambition for the honors of a leader and feastmaker, which can never be his unless he is truthful and generous, as well as brave, and ever mindful of his personal chastity and honor. There were many ceremonial customs which had a distinct moral influence; the woman was rigidly secluded at certain periods, and the young husband was forbidden to approach his own wife when preparing for war or for any religious event. The public or tribal position of the Indian is entirely dependent his private virtue, and he is never permitted to forget that he does not live to himself alone, but to his tribe and his clan. Thus habits of perfect self-control were early established, and there were no unnatural conditions or complex temptations to beset him until he was met and overthrown by a stronger race.

It was our belief that the love of possessions is a weakness to be overcome. Its appeal is to the material part, and if allowed its way it will in time disturb the spiritual balance of the man. Therefore the child must early learn the beauty of generosity. He is taught to give what he prizes most, and that he may taste the happiness of giving, he is made at an early age the family almoner. If a child is inclined to be grasping, or to cling to any of his little possessions, legends are related to him, telling of the contempt and disgrace falling upon the ungenerous and mean man.

The true Indian sets no price upon either his property or his labor. His generosity is only limited by his strength and ability. He regards it as an honor to be selected for a difficult or dangerous service, and would think it shame to ask for any reward, saying rather: "Let him whom I serve express his thanks according to his own bringing up and his sense of honor!"

Nevertheless, he recognizes rights in property. To steal from one of his own tribe would be indeed disgrace if discovered, the name of "Wamanon," or Thief, is fixed upon him forever as an unalterable. The only exception to the rule is in the case of food, which is always free to the hungry if there is none by to offer it. Other protection than the moral law there could not be in an Indian community, where there were neither locks nor doors, and everything was open and easy of access to all comers.

It is said that, in the very early days, lying was a capital offense among us. Believing that the deliberate liar is capable of committing any crime behind the screen of cowardly untruth and double-dealing, the destroyer of mutual confidence was summarily put to death, that the evil might go no further.

Dr. Charles A. Eastman, born Ohiyesa (Santee Sioux), "Chapter 4: Barbarism and the Moral Code," The Soul of the Indian: An Interpretation, 1911

One great difference in our ways is that, like the early Christians, the Indian was a Socialist. The tribe owned the ground, the rivers and the game; only personal property was owned by the individual, and even that, it was considered a shame to greatly increase. For they held that greed grew into crime, and much property made men forget the poor. Our answer to this is that, without great property, that is power in the hands of one man, most of the great business enterprises of the world could not have been; especially enterprises that required the prompt action impossible in a national commission. All great steps in national progress have been through some one man, to whom the light came, and to whom our system gave the power to realize his idea.

The Indian's answer is, that all good things would have been established by the nation as it needed them; anything coming sooner comes too soon. The price of a very rich man is many poor ones, and peace of mind is worth more than railways and skyscrapers.

In the Indian life there was no great wealth, so also poverty and starvation were unknown, excepting under the blight of national disaster, against which no system can insure. Without a thought of shame or mendicancy, the young, helpless and aged all were cared for by the nation that, in the days of their strength, they were taught and eager to serve.

And how did it work out? Thus: Avarice, said to be the root of all evil, and the dominant characteristic of our race, was unknown among Indians, indeed it was made impossible by the system they had developed.

Ernest Thompson Seton, "Chapter II: The Spartans of the West," The Book of Woodcraft, 1912

Out of the Indian approach to life there came a great freedom, an intense and absorbing respect for life, enriching faith in a Supreme Power, and principles of truth, honesty, generosity, equity, and brotherhood as a guide to mundane relations.

Luther Standing Bear (Oglala Sioux), 1868-1937

They spoke very loudly when they said their laws were made for everybody; but we soon learned that although the expected us to keep them, they thought nothing of breaking them themselves. Their Wise Ones said we might have their religion, but when we tried to understand it we found that there were too many kinds of religion among white men for us to understand, and that scarcely any two white men agreed which was the right one to learn. This bothered us a good deal until we saw that the white man did not take his religion any more seriously than he did his laws, and that he kept both of them just behind him, like Helpers, to use when they might do him good in his dealings with strangers....We have never been able to understand the white man, who fools nobody but himself.

Plenty-Coups (Crow), Plenty-Coups, Chief of the Crows, published 1962

For a long time Native Americans have been rebuking textbook authors for reserving the adjective civilized for European cultures. In 1927 an organization of Native leaders called the Grand Council Fire of American Indians criticized textbooks as "unjust to the life of our people." They went on to ask, "What is civilization? Its marks are a noble religion and philosophy, original arts, stirring music, rich story and legend. We had these. Then we were not savages, but a civilized race." Even an appreciative treatment of Native cultures reinforces ethnocentrism so long as it does not challenge the primitive-to-civilized continuum. This continuum inevitably conflates the meaning of civilized in everyday conversation—"refined or enlightened"—with "having a complex division of labor," the only definition that anthropologists defend. When we consider the continuum carefully, it immediately becomes problematic. Was the Third Reich civilized, for instance? Most anthropologists would answer yes. In what ways do we prefer the civilized Third Reich to the more primitive Arawak nation that Columbus encountered? If we refuse to label the Third Reich civilized, are we not using the term to imply a certain comity? If so, we must consider the Arawaks civilized, and we must also consider Columbus and his Spaniards primitive if not savage. Ironically, societies characterized by a complex division of labor are often marked by inequality and capable of supporting large specialized armies. Precisely these "civilized" societies are likely to resort to savage violence in their attempts to conquer "primitive" societies.

James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me

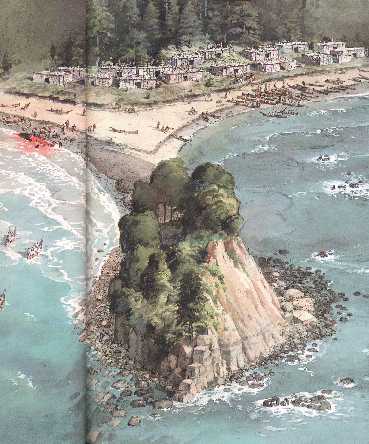

Columbus and his successors were not coming into an empty wilderness, but into a world which in some places was as densely populated as Europe itself, where the culture was complex, where human relations were more egalitarian than in Europe, and where the relations among men, women, children, and nature were more beautifully worked out than perhaps any place in the world.

They were people without a written language, but with their own laws, their poetry, their history kept in memory and passed on, in an oral vocabulary more complex than Europe's, accompanied by song, dance, and ceremonial drama. They paid careful attention to the development of personality, intensity of will, independence and flexibility, passion and potency, to their partnership with one another and with nature.

John Collier, an American scholar who lived among Indians in the 1920s and 1930s in the American Southwest, said of their spirit: "Could we make it our own, there would be an eternally inexhaustible earth and a forever lasting peace."

Perhaps there is some romantic mythology in that. But the evidence from European travelers in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, put together recently by an American specialist on Indian life, William Brandon, is overwhelmingly supportive of much of that "myth." Even allowing for the imperfection of myths, it is enough to make us question, for that time and ours, the excuse of progress in the annihilation of races, and the telling of history from the standpoint of the conquerors and leaders of Western civilization.

Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States 1492—Present, Chapter 1, Columbus, the Indians, and Human Progress

More on uncivilized Indians

"Civilizing" marriage among Indians

Related links

Savage Indians

"Primitive" Indian religion

Indians gave us enlightenment

Native vs. non-Native Americans: a summary

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.