An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Ten Little Pilgirms and Indians:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Ten Little Pilgirms and Indians: An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Ten Little Pilgirms and Indians:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Ten Little Pilgirms and Indians:

In a bookstore recently I came across the book One Little, Two Little, Three Little Pilgrims by B.G. Hennessey. Since I was just discussing the stereotypical "Ten Little Indians" song online, this was an interesting coincidence. It raises the question of how children's books are handling Thanksgiving these days.

To Hennessey's credit, the book scrupulously devotes equal time to the Pilgrims and Indians. It also devotes equal time to boys and girls. The book's twin refrains are:

"Ten little Pilgrim boys and girls"

"Ten little Wampanoag boys and girls"

So does perfect equality equal perfection? Hardly. These children are so happy-go-lucky they should be in a Disney movie. A reader of this book would never know the Pilgrims endured hardships.

Another children's book, The Pilgrims' First Thanksgiving by Ann McGovern, mentions that "many" Pilgrims died and that Squanto taught them how to gather and grow food. But even this account ignores many pertinent facts. For instance:

Incidentally, the attendees at the 1621 feast did include enough boys (16) and girls (8) to fill the "ten little Pilgrims" book. Good thing, too, because only 28 adults besides the children survived. Since the Wampanoag chief Massasoit reportedly brought 90 men to the festivities, little Indian boys and girls were probably scarce.

Thanksgiving: the real story

The attack on the Pequot village wasn't just an aberration. An essay in the East Texas Review (12/2/04) gives us "Thanksgiving: Its True History":

The Puritans were religious radicals being driven into exile out of England. Since their story is well known, I will not repeat it here. They settled and built a colony which they called the "Plymouth Plantation", near the ruins of a former Native village of the Pawtuxet Nation. Only one Pawtuxet had survived, a man named Squanto, who had spent time as a slave to the English. Since he understood the language and customs of the Puritans, he taught them to use the corn growing wild from the abandoned fields of the village, taught them to fish, and about the foods, herbs and fruits of this land. Squanto also negotiated a peace treaty between the Puritans and the Wampanoag Nation, a very large Native nation which totally surrounded the new Plymouth Plantation. Because of Squanto's efforts, the Puritans enjoyed almost 15 years of peaceful harmony with the surrounding Natives, and they prospered.

At the end of their first year, the Puritans held a great feast following the harvest of food from their new farming efforts. The feast honored Squanto and their friends, the Wampanoags. The feast was followed by 3 days of "thanksgiving" celebrating their good fortune. This feast produced the image of the first Thanksgiving that we all grew up with as children. However, things were doomed to change.

Until approximately 1629, there were only about 300 Puritans living in widely scattered settlements around New England. As word leaked back to England about their peaceful and prosperous life, more Puritans arrived by the boatloads. As the numbers of Puritans grew, the question of ownership of the land became a major issue. The Puritans came from the belief of individual needs and prosperity, and had no concept of tribal living or group sharing. It was clear that these heathen savages had no claim on the land because it had never been subdued, cultivated and farmed in the European manner, and there were no fences or other boundaries marked. The land was clearly "public domain", and there for the taking. This attitude met with great resistance from the original Puritans who held their Native benefactors in high regard. These first Puritan settlers were summarily excommunicated and expelled from the church.

With Bible passages in their hands to justify their every move, the Puritans began their march inland from the seaside communities. Joined by British settlers, they seized land, took the strong and young Natives as slaves to work the land, and killed the rest. When they reached the Connecticut Valley around 1633, they met a different type of force. The Pequot Nation, very large and very powerful, had never entered into the peace treaty negotiated by Squanto as had other New England Native nations. When 2 slave raiders were killed by resisting Natives, the Puritans demanded that the killers be turned over. The Pequot refused. What followed was the Pequot War, the bloodiest of the Native wars in the northeast.

An army of over 200 settlers was formed, joined by over 1,000 Narragansett warriors. Because of the lack of fighting experience, and the vast numbers of the fierce Pequot warriors, Commander John Mason elected not to stage an open battle. Instead, the Pequot were attacked, one village at a time, in the hours before dawn. Each village was set on fire with its sleeping Natives burned alive. Women and children over 14 were captured to be sold as slaves; other survivors were massacred. The Natives were sold into slavery in The West Indies, the Azures, Spain, Algiers and England; everywhere the Puritan merchants traded. The slave trade was so lucrative that boatloads of 500 at a time left the harbors of New England.

In 1641, the Dutch governor of Manhattan offered the first scalp bounty; a common practice in many European countries. This was broadened by the Puritans to include a bounty for Natives fit to be sold for slavery. The Dutch and Puritans joined forces to exterminate all Natives from New England, and village after village fell. Following an especially successful raid against the Pequot in what is now Stanford, Connecticut, the churches of Manhattan announced a day of "thanksgiving" to celebrate victory over the savages. This was the 2nd Thanksgiving. During the feasting, the hacked off heads of Natives were kicked through the streets of Manhattan like soccer balls.

The killing took on a frenzy, with days of thanksgiving being held after each successful massacre. Even the friendly Wampanoag did not escape. Their chief was beheaded, and his head placed on a pole in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where it remained for 24 years. Each town held thanksgiving days to celebrate their own victories over the Natives until it became clear that there needed to be an order to these special occasions. It was George Washington who finally brought a system and a schedule to thanksgiving when he declared one day to be celebrated across the nation as Thanksgiving Day.

It was Abraham Lincoln who decreed Thanksgiving Day to be a legal national holiday during the Civil War, on the same day and at the same time he was ordering troops to march against the Sioux in Minnesota.

In our society, it is not uncommon for our modern celebrations to have arisen from evil beginnings. Over the centuries, Thanksgiving has become a special day to join with loved ones in an offering of thanks for our blessings. Some give their time to help with the homeless and hungry. It is now a day of giving, and of honor, and of true thanksgiving.

In your Thanksgivings to come, I would ask that you offer a silent prayer for the spirits of those who were sacrificed so long ago. You and I did not commit these atrocities, and we are certainly not responsible for the behavior of our ancestors be they red, white, black or yellow.

However, we are charged with the responsibility of learning our true history, and of having the courage to behave with honor and dignity toward our fellow man. If the lessons of history are not learned, they will repeat themselves.

In short, don't let the harmony of the first thanksgiving fool you. The Puritans were religious fanatics fleeing a more tolerant and secular Europe. The following posting (11/24/01) debunks the idea that they were anything else:

There is nothing noble about the puritans. They were a divisive and extremist sect of the protestant Anglican faith who were not satisfied with the middle of the road approach to religion that King James I took when he came to the throne of England. They were involved in many civil and Parliamentary skirmishes during the reigns of Great Bess, James I and his son, Charles I due to their insistence to conform the National Church of England (of which the monarch was the head) to the word of God in worship, government and religious practice. They wanted strict, literal interpretation of the bible as public policy in spite of the crown. (Can you say "Taliban and Islam?") That's like the extreme fundamentalist Christian right attempting to usurp the Constitution and Bill of Rights because it was too secular for their tender sensibilities—wait! Isn't that what's going on now?

For more on this topic, see The Pilgrims: Children of the Devil (aptly subtitled "Puritan Doomsday Cult Plunders Paradise").

The myth of our Pilgrim forefathers

From the NY Times:

July 9, 2006

Op-Ed Contributor

Immigration — and the Curse of the Black Legend

By TONY HORWITZ

Vineyard Haven, Mass.

COURSING through the immigration debate is the unexamined faith that American history rests on English bedrock, or Plymouth Rock to be specific. Jamestown also gets a nod, particularly in the run-up to its 400th birthday, but John Smith was English, too (he even coined the name New England).

So amid the din over border control, the Senate affirms the self-evident truth that English is our national language; "It is part of our blood," Lamar Alexander, Republican of Tennessee, says. Border vigilantes call themselves Minutemen, summoning colonial Massachusetts as they apprehend Hispanics in the desert Southwest. Even undocumented immigrants invoke our Anglo founders, waving placards that read, "The Pilgrims didn't have papers."

These newcomers are well indoctrinated; four of the sample questions on our naturalization test ask about Pilgrims. Nothing in the sample exam suggests that prospective citizens need know anything that occurred on this continent before the Mayflower landed in 1620. Few Americans do, after all.

This national amnesia isn't new, but it's glaring and supremely paradoxical at a moment when politicians warn of the threat posed to our culture and identity by an invasion of immigrants from across the Mexican border. If Americans hit the books, they'd find what Al Gore would call an inconvenient truth. The early history of what is now the United States was Spanish, not English, and our denial of this heritage is rooted in age-old stereotypes that still entangle today's immigration debate.

Forget for a moment the millions of Indians who occupied this continent for 13,000 or more years before anyone else arrived, and start the clock with Europeans' presence on present-day United States soil. The first confirmed landing wasn't by Vikings, who reached Canada in about 1000, or by Columbus, who reached the Bahamas in 1492. It was by a Spaniard, Juan Ponce de León, who landed in 1513 at a lush shore he christened La Florida.

Most Americans associate the early Spanish in this hemisphere with Cortés in Mexico and Pizarro in Peru. But Spaniards pioneered the present-day United States, too. Within three decades of Ponce de León's landing, the Spanish became the first Europeans to reach the Appalachians, the Mississippi, the Grand Canyon and the Great Plains. Spanish ships sailed along the East Coast, penetrating to present-day Bangor, Me., and up the Pacific Coast as far as Oregon.

From 1528 to 1536, four castaways from a Spanish expedition, including a "black" Moor, journeyed all the way from Florida to the Gulf of California — 267 years before Lewis and Clark embarked on their much more renowned and far less arduous trek. In 1540, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado led 2,000 Spaniards and Mexican Indians across today's Arizona-Mexico border — right by the Minutemen's inaugural post — and traveled as far as central Kansas, close to the exact geographic center of what is now the continental United States. In all, Spaniards probed half of today's lower 48 states before the first English tried to colonize, at Roanoke Island, N.C.

The Spanish didn't just explore, they settled, creating the first permanent European settlement in the continental United States at St. Augustine, Fla., in 1565. Santa Fe, N.M., also predates Plymouth: later came Spanish settlements in San Antonio, Tucson, San Diego and San Francisco. The Spanish even established a Jesuit mission in Virginia's Chesapeake Bay 37 years before the founding of Jamestown in 1607.

Two iconic American stories have Spanish antecedents, too. Almost 80 years before John Smith's alleged rescue by Pocahontas, a man by the name of Juan Ortiz told of his remarkably similar rescue from execution by an Indian girl. Spaniards also held a thanksgiving, 56 years before the Pilgrims, when they feasted near St. Augustine with Florida Indians, probably on stewed pork and garbanzo beans.

The early history of Spanish North America is well documented, as is the extensive exploration by the 16th-century French and Portuguese. So why do Americans cling to a creation myth centered on one band of late-arriving English — Pilgrims who weren't even the first English to settle New England or the first Europeans to reach Plymouth Harbor? (There was a short-lived colony in Maine and the French reached Plymouth earlier.)

The easy answer is that winners write the history and the Spanish, like the French, were ultimately losers in the contest for this continent. Also, many leading American writers and historians of the early 19th century were New Englanders who elevated the Pilgrims to mythic status (the North's victory in the Civil War provided an added excuse to diminish the Virginia story). Well into the 20th century, standard histories and school texts barely mentioned the early Spanish in North America.

While it's true that our language and laws reflect English heritage, it's also true that the Spanish role was crucial. Spanish discoveries spurred the English to try settling America and paved the way for the latecomers' eventual success. Many key aspects of American history, like African slavery and the cultivation of tobacco, are rooted in the forgotten Spanish century that preceded English arrival.

There's another, less-known legacy of this early period that explains why we've written the Spanish out of our national narrative. As late as 1783, at the end of the Revolutionary War, Spain held claim to roughly half of today's continental United States (in 1775, Spanish ships even reached Alaska). As American settlers pushed out from the 13 colonies, the new nation craved Spanish land. And to justify seizing it, Americans found a handy weapon in a set of centuries-old beliefs known as the "black legend."

The legend first arose amid the religious strife and imperial rivalries of 16th-century Europe. Northern Europeans, who loathed Catholic Spain and envied its American empire, published books and gory engravings that depicted Spanish colonization as uniquely barbarous: an orgy of greed, slaughter and papist depravity, the Inquisition writ large.

Though simplistic and embellished, the legend contained elements of truth. Juan de Oñate, the conquistador who colonized New Mexico, punished Pueblo Indians by cutting off their hands and feet and then enslaving them. Hernando de Soto bound Indians in chains and neck collars and forced them to haul his army's gear across the South. Natives were thrown to attack dogs and burned alive.

But there were Spaniards of conscience in the New World, too: most notably the Dominican priest Bartolomé de Las Casas, whose defense of Indians impelled the Spanish crown to pass laws protecting natives. Also, Spanish brutality wasn't unique; English colonists committed similar atrocities. The Puritans were arguably more intolerant of natives than the Spanish and the Virginia colonists as greedy for gold as any conquistador. But none of this erased the black legend's enduring stain, not only in Europe but also in the newly formed United States.

"Anglo Americans," writes David J. Weber, the pre-eminent historian of Spanish North America, "inherited the view that Spaniards were unusually cruel, avaricious, treacherous, fanatical, superstitious, cowardly, corrupt, decadent, indolent and authoritarian."

When 19th-century jingoists revived this caricature to justify invading Spanish (and later, Mexican) territory, they added a new slur: the mixing of Spanish, African and Indian blood had created a degenerate race. To Stephen Austin, Texas's fight with Mexico was "a war of barbarism and of despotic principles, waged by the mongrel Spanish-Indian and Negro race, against civilization and the Anglo-American race." It was the manifest destiny of white Americans to seize and civilize these benighted lands, just as it was to take the territory of Indian savages.

From 1819 to 1848, the United States and its army increased the nation's area by roughly a third at Spanish and Mexican expense, including three of today's four most populous states: California, Texas and Florida. Hispanics became the first American citizens in the newly acquired Southwest territory and remained a majority in several states until the 20th century.

By then, the black legend had begun to fade. But it seems to have found new life among immigration's staunchest foes, whose rhetoric carries traces of both ancient Hispanophobia and the chauvinism of 19th-century expansionists.

Representative J. D. Hayworth of Arizona, who calls for deporting illegal immigrants and changing the Constitution so that children born to them in the United States can't claim citizenship, denounces "defeatist wimps unwilling to stand up for our culture" against alien "invasion." Those who oppose making English the official language, he adds, "reject the very notion that there is a uniquely American identity, or that, if there is one, that it is superior to any other."

Representative Tom Tancredo of Colorado, chairman of the House Immigration Reform Caucus, depicts illegal immigration as "a scourge" abetted by "a cult of multiculturalism" that has "a death grip" on this nation. "We are committing cultural suicide," Mr. Tancredo claims. "The barbarians at the gate will only need to give us a slight push, and the emaciated body of Western civilization will collapse in a heap."

ON talk radio and the Internet, foes of immigration echo the black legend more explicitly, typecasting Hispanics as indolent, a burden on the American taxpayer, greedy for benefits and jobs, prone to criminality and alien to our values — much like those degenerate Spaniards of the old Southwest and those gold-mad conquistadors who sought easy riches rather than honest toil. At the fringes, the vilification is baldly racist. In fact, cruelty to Indians seems to be the only transgression absent from the familiar package of Latin sins.

Also missing, of course, is a full awareness of the history of the 500-year Spanish presence in the Americas and its seesawing fortunes in the face of Anglo encroachment. "The Hispanic world did not come to the United States," Carlos Fuentes observes. "The United States came to the Hispanic world. It is perhaps an act of poetic justice that now the Hispanic world should return."

America has always been a diverse and fast-changing land, home to overlapping cultures and languages. It's an homage to our history, not a betrayal of it, to welcome the latest arrivals, just as the Indians did those tardy and uninvited Pilgrims who arrived in Plymouth not so long ago.

Tony Horwitz, the author of "Confederates in the Attic" and "Blue Latitudes," is writing a book on the early exploration of North America.

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company

The politics of Thanksgiving

Given the actual history of the United States, what's up with our glorification of Thanksgiving? What does it say about us that it's one of our most revered holidays?

As James W. Loewen notes in his masterful Lies My Teacher Told Me, Thanksgiving is an example of American myth-making:

Thanksgiving is the occasion on which we give thanks to God as a nation for the blessings that He [sic] hath bestowed on us. More than any other celebration, more even than such overtly patriotic holidays as Independence Day and Memorial Day, Thanksgiving celebrates our ethnocentrism.

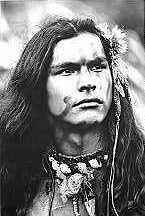

Just look at the adjacent image, for instance. The Pilgrim is handsome, clean-shaven, even blue-eyed. The only surprise is that he isn't blond like the phony John Smith in Pocahontas.

Conservatives use Thanksgiving to construct a vision of America founded by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants—in other words, people just like them. Jerry Falwell pushes this vision in his essay What Thanksgiving Means to America, as does a Christian organization, the Creativity Ministry, with its puppet play. This vision is never about how the white men would've failed and died without the intervention of strangers (Indians) with an alien culture and god. It's about how God favored his children with help, thus proving Euro-Americans were the "chosen people."

The not-so-subtle message is that the WASPs who founded the nation own the nation. This land is their land, not ours, so we can't deny them its wealth and power. In other words, accept the status quo; love America the way it is or leave it.

As Loewen notes, the Thanksgiving myth is a prime example of a larger myth: that our nation's founders were heroic figures who embarked on a great enterprise. Our cultural products—textbooks, monuments, and holidays—honor Christopher Columbus, Juan de Oñate, and the others who made this country what it is. We show who our heroes are by putting them on coins and currency, naming schools and towns after them, and celebrating them in fact and fiction.

Conservatives use these cultural icons to construct their mythological America—a place that wasn't inhabited by Indians, settled by Spaniards, or built on the backs of Africans. It's up to us to deconstruct them.

By Robert Jensen, AlterNet

Posted on November 23, 2006, Printed on November 27, 2006

How does a country deal with the fact that some of its most revered historical figures had certain moral values and political views virtually identical to Nazis? Here's how "respectable" politicians, pundits, and professors play the game: When invoking a grand and glorious aspect of our past, then history is all-important. We are told how crucial it is for people to know history, and there is much hand wringing about the younger generations' lack of knowledge about, and respect for, that history.

In the United States, we hear constantly about the deep wisdom of the founding fathers, the adventurous spirit of the early explorers, the gritty determination of those who "settled" the country — and about how crucial it is for children to learn these things.

But when one brings into historical discussions any facts and interpretations that contest the celebratory story and make people uncomfortable — such as the genocide of indigenous people as the foundational act in the creation of the United States — suddenly the value of history drops precipitously and one is asked, "Why do you insist on dwelling on the past?"

This is the mark of a well-disciplined intellectual class — one that can extol the importance of knowing history for contemporary citizenship and, at the same time, argue that we shouldn't spend too much time thinking about history.

This off-and-on engagement with history isn't of mere academic interest; as the dominant imperial power of the moment, U.S. elites have a clear stake in the contemporary propaganda value of that history. Obscuring bitter truths about historical crimes helps perpetuate the fantasy of American benevolence, which makes it easier to sell contemporary imperial adventures — such as the invasion and occupation of Iraq — as another benevolent action.

Any attempt to complicate this story guarantees hostility from mainstream culture. After raising the barbarism of America's much-revered founding fathers in a lecture, I was once accused of trying to "humble our proud nation" and "undermine young people's faith in our country."

Yes, of course — that is exactly what I would hope to achieve. We should practice the virtue of humility and avoid the excessive pride that can, when combined with great power, lead to great abuses of power.

History does matter, which is why people in power put so much energy into controlling it. The United States is hardly the only society that has created such mythology. While some historians in Great Britain continue to talk about the benefits that the empire brought to India, political movements in India want to make the mythology of Hindutva into historical fact.

Abuses of history go on in the former empire and the former colony. History can be one of the many ways we create and impose hierarchy, or it can be part of a process of liberation. The truth won't set us free, but the telling of truth at least opens the possibility of freedom.

As Americans sit down on Thanksgiving Day to gorge themselves on the bounty of empire, many will worry about the expansive effects of overeating on their waistlines. We would be better to think about the constricting effects of the day's mythology on our minds.

AlterNet orginally ran this article on Thanksgiving 2005.

Robert Jensen is a journalism professor at the University of Texas at Austin, and the author of, most recently, "The Heart of Whiteness: Confronting Race, Racism and White Privilege" (City Lights Books).

(c) 2006 Independent Media Institute. All rights reserved.

The Thanksgiving myth deconstructed

Teaching About Thanksgiving

Giving Thanks to America's Indians: Native Resurgence Spurs Hope

First Feast More Fiction Than Fact? Author says Thanksgiving tale invented by tradition, not supported by history

The Truth About the First Thanksgiving (by James W. Loewen)

The Truth About Squire Romolee

Deconstructing the Myths of "The First Thanksgiving"

Indian Comics Irregular #15: "TV's First Thanksgiving"

Indian Comics Irregular #2: "The Truth About Thanksgiving"

The Thanksgiving myth reconstructed

Thanksgiving on the Net: Roast Bull with Cranberry Sauce

Thanksgiving in the Stereotype of the Month contest

Girl cries over Indian costume

Playing Indian for Thanksgiving

Fuzzy Indians in (Lil) Green Patch

Thanksgiving celebrates "gratitude, humility, and inclusiveness"

Student is elected "Chief Sun Slayer" to sell land for wampum

Brooks's "Real Thanksgiving": Massasoit wanted a casino

U. of Florida cartoon: NCAA scolds Gator killing Seminole

Preschoolers make headbands, drums to learn about Indians

"Noble Savage Indianism" is Indians' "fantasy group heritage"

Non Sequitur equates grievances of Indians and Pilgrims

Yahoo e-card shows turkey dressed as Indian, whooping

Editorial defends feathered kids at school's Thanksgiving

Fashion layout depicts "stoic" Natives "getting restless"

Thanksgiving script has Indian in headdress saying "ugh"

Students wear headdresses and war paint for Thanksgiving

The 2008 Plimouth controversy

Stupid stereotypes at Plimouth

Girl cries over Indian costume

The 2008 Claremont controversy

Michelle Raheja responds

Parents to Indians: Go to hell

Police prevent Thanksgiving brawl

Playing Indian for Thanksgiving

Other Thanksgiving resources

American Indian Heritage Month: resources for the media, schools, and the Web

Kid Info: The Plymouth Colony

More on Thanksgiving

Peanuts' Thanksgiving propaganda

Germans film Pilgrims in Salem

School full of stereotypical Indians

America's first capitalists

1676 Thanksgiving celebrated beheading

Pilgrims initiated genocide

Texas held the first Thanksgiving?

Pilgrims sought religious freedom?

Pilgrims owned the land?

Thank God for killing Patuxets

More Thanksgiving myths debunked

Every day is Thanksgiving for Indians

How Navajos celebrate Thanksgiving

Teaching teachers about Thanksgiving

Pilgrim and Indian donated to hospital

Thanksgiving author vs. Indian educator

New England's myth-conception

Indians one day a year

Rolo wrong about Thanksgiving

Liberals and conservatives vs. Indians

Piscataway chief deprograms Indians

Thanksgiving stereotypes hurt

Carving away at Thanksgiving myths

Indian "mice" are worthless

Cardboard version of Thanksgiving

Two countries, two myths

Thanksgiving as immigration aid

Why Plymouth, not Jamestown?

Feds recognize Pilgrims' rescuers

Dwelling on the past

The two Thanksgivings

Be thankful for what?

Dueling views on how to teach

The first Thanksgiving(s)

Teaching truth is hateful?

Wampanoag weren't invited

No, Virginia, there wasn't a Thanksgiving

National Day of Mourning

Thanksgiving = happy and innocent?

Another dress-up holiday

Thanksgiving on the History Channel

The first Thanksgiving myth

Teaching kids about Turkey Day

Indians critique Mayflower

Unpredictable Pilgrims and Indians

More on America's holiday myths

Fun 4th of July facts

This ain't no party: a Columbus Day rant

Tricking or treating Indians

Related links

Democracy rocks—with Indian help

Gingrich flunks "American Culture"

Native vs. non-Native Americans: a summary

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.