Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Terrorist or Hero?

Poster of Geronimo at local pub stirs controversy

By Zsombor Peter

Staff Writer

GALLUP — Almost a century after his death, Geronimo continues to inspire controversy.

One hundred years ago, it was the Chiricahua Apache leader's exploits across the Southwest, making him a freedom fighter to his people and outlaw to the federal government. But on a recent Friday night in Gallup, all it took was a poster.

It made me sad

Norman Brown, a Navajo filmmaker and longtime Native rights activist, was catching up with friends at the Coal Street Pub on the night of April 20 when he saw it, about chest high, nailed to a wall leading to the kitchen.

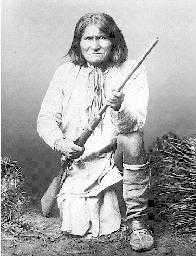

It's an iconic image, a photograph of Geronimo on one knee clutching a rifle across his chest. Brown had seen it a hundred times. But what caught his attention this time was the "wanted" label above it something about crimes against the government a $5,000 reward, and the shackle around his ankle.

History remembers Geronimo as a legend and a hero to his people. But during his time, the Apache leader was, as the poster attests, a wanted man. His raids across Arizona and New Mexico, following the murder of his mother, wife and children by Mexicans, caught the attention of the U.S. Army, and one Gen. George Crook. The general placed Geronimo and his band on a reservation, but didn't keep him there long. After another decade of fighting with settlers, Geronimo agreed to go to Florida, where his family was being held, but fled again. Now with Gen. Nelson Miles and 5,000 troops after him and his 35 men, Geronimo remained at large for another 18 months. Confined to Fort Sill, Okla., by presidential orders, and contrary to the terms he agreed to with Miles, Geronimo lived out the rest of his days farming and raising stock until his death in 1909.

Seeing the wanted poster, Brown said, "it made me sad instantly."

Then he noticed the John Wayne photo behind him.

"You either see John Wayne as an actor, or you see him as an Indian killer," he said.

There's no doubt about which view Brown takes. He started putting the two together. But just to make sure he wasn't overreacting, he asked his friends, some white, some Hispanic, to take a look at the Geronimo poster for themselves. They agreed that Brown had a reason to feel offended.

Hoping he might get the poster removed, he asked a waitress behind the bar for the manager. That's when things started to escalate.

Things fall apart

Brown insists the waitress, Lisa Mares, belittled his concerns and that another waiter physically threatened him. Mares insists that Brown was being rude, provoking the other waiter, and demanding not asking that the poster come down.

Pub co-owner Ramon Chavez was playing in the house band when the confrontation started. When the band took a break a little before 8 p.m., he headed toward the kitchen and came across the scene.

"I went up to the bar and they were arguing ... it was just really out of hand," he recalled. "Someone was calling someone a dumbass. There was finger pointing. Voices were raised. Everyone was mad.

"There was no talking," he said. "When I got involved there was only screaming."

And Brown, said Chavez, was doing as much screaming as anyone.

But that's not exactly what two other witnesses saw. Andru Ziwasimon, an Albuquerque-based family physician, had met Brown earlier that evening through a mutual friend. Alan Drauer, who heads the local Teach for America office, was a pub regular and an acquaintance of Chavez's. According to both men, Brown had raised his voice along with everyone else, but not to the point of screaming.

Brown didn't come off as aggressive, Drauer said, "but I could definitely tell he was a little stressed out."

Ziwasimon said Brown was "totally calm," more shocked than anything.

Either way, when Brown refused to leave, Chavez decided he'd had enough. He called the police to have Brown removed. Brown and Ziwasimon heard Chavez say something about a drunk. According to the Metro Dispatch recording, Chavez said he did not think Brown was drunk, just irate.

Feeling insulted and discriminated, asked to leave simply for raising his concerns about a poster, Brown wanted to stand his ground. His friends convinced him to leave. A minute after his first call, Chavez called the police back and canceled his request.

To Chavez, the dispute had nothing to do with the poster. Amid all the commotion, Chavez said, he wasn't even sure which poster Brown was talking about. All he could figure out was that a customer had a problem with his interior decorating.

"If you don't like what's on my wall you can leave," Chavez said. "I have 300 pictures on these walls. I don't know what I've got."

To Chavez, the dispute was about the way he felt Brown treated his staff.

"If anybody's rude to my servers, raising their voices ... it's my job to protect my servers," he said. "What do you think I'm going to do? These are like my kids."

If Brown had calmed down, Chavez said, they could have talking things through.

Brown insists we was calm.

No apologies

Chavez ended up taking the poster down the next day. It just wasn't worth the trouble of keeping up. It's been replaced by a beer ad.

Even when the poster was up, Chavez said he'd never taken a very close look at it, certainly not close enough to notice the shackles. Like the hundreds of other photos and posters covering the pub's red walls, he simply considered it a record of the area's past. None were meant to offend.

"It's a piece of history," Mares agreed.

Chavez, who is of Mexican heritage, pointed out another photo of Mexican immigrants being loaded onto the back of a flatbed truck for deportation.

"I want to honor Gallup. That's why it's up there," he said.

For a restaurant that wants to honor Gallup, though, a town that's one-third American Indian, in the heart of a county that's well over 50 percent American Indian, there are very few pictures of American Indians on the walls. Chavez said he never considered that.

Neither has Brandon Neahusan, who heads to the pub a few times a week. He likes the atmosphere, which all the photos and posters add to, but has never given any one much attention, least of all the one of Geronimo. Until he heard about the Friday night incident the following week, he didn't even know the pub had a poster of Geronimo.

"I had to ask where it was," he said.

By then, Chavez had taken it down. But from what he's heard, Neahusan doesn't consider it all that offensive.

"At this point in history I just think it has relegated itself to an item of pop culture," he said.

To Brown, it's as relevant as ever.

Brown's father, a Navajo Code Talker, had taught him that the Apache and Navajo were of a common ancestor: the Athabaskans.

"It was as if I saw Manuelito sitting there in shackles," he said, referring to the revered Navajo chief. "I saw him as my ch, my grandfather, sitting there with chains around his ankles."

With so much personal weight behind the poster, Brown believes it's about more than him and Chavez.

"It's not an owner, customer issue," Brown said. Nor, he added, is it "about the citizens of Gallup. It's about the institutional racism that's here ... that continues to allow this kind of discrimination."

From the lack of Navajo education in the county's public schools to a local American Indian jewelry industry that still exploits their labor, Brown said, what happened that Friday night was nothing new.

Chavez isn't apologizing. But even if he did, Brown said he couldn't accept.

"We've accepted it for too long," he said.

Still holding on to the kind of anger that brought tears to his eyes days later, Brown does not want to forget what happened. He's talking of boycotts and civil rights panels, and he's not excluding legal action.

"If I just accept it," Brown asked, "what do you think's going to happen? Nothing."

Rob's comment

Depicting Geronimo as if he were a terrorist or criminal when he was fighting for his freedom is wrong and stereotypical.

If the poster was indeed the famous shot of Geronimo kneeling, something's wrong. Geronimo wasn't wearing a shackle when that picture was taken. Nor would it make sense to create a "Wanted" poster of someone already in captivity.

So the poster apparently is a fabrication. Contrary to Chavez's claims, it's not "history." It exists to belittle Geronimo and his cause, not to record history. It's not unlike the photos taken in Abu Ghraib to record the humiliation of the Muslim captives.

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.