Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Published: August 23, 2006 04:05 am

Hollywood likes Colonial woman's story

Hannah Duston, 300-year-old movie star?

By Shawn Regan

THE EAGLE-TRIBUNE (NORTH ANDOVER, Mass.)

HAVERHILL, Mass. — Several independent moviemakers and scriptwriters are interested in bringing controversial Colonial heroine Hannah Duston to the big screen.

Scott Baron, CEO of Los Angeles-based Dynamo Entertainment, a new filmmaking company that seeks to produce as many as five low- to mid-budget movies per year, said his writers have already started developing a script about Duston "to see if we can do her story justice while creating a moving and exciting film."

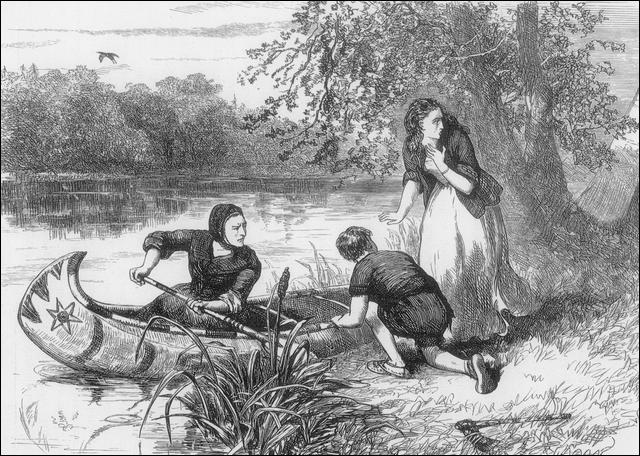

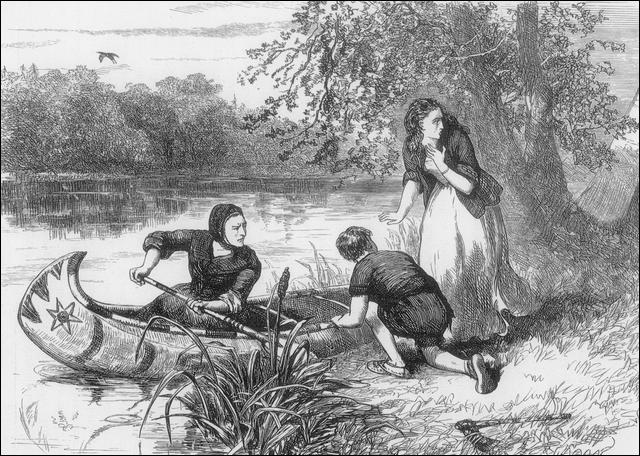

Duston made history March 15, 1697, when she was kidnapped by Abenaki Indians, who killed her infant daughter by bashing the baby's head against a tree. Two weeks later on March 30, Duston escaped with her nursemaid and a young boy from an island in the middle of the Merrimack River near present-day Concord, N.H., by killing and scalping as many as 10 of her captors.

"The Colonial time and locale of the story really caught my eye," said Baron, stepson of prolific movie producer Art Levinson. "There seems to be such a reliance on weaponry, gadgets and explosions these days. But Hannah Duston's story is compelling without relying on such devices.

"This is a story not only with a strong female lead but also a solid tale of triumph over adversity and overwhelming odds," Baron said.

Hollywood has served up such recent movies based in Colonial Massachusetts as "Amistad," "The Crucible" and "The Scarlet Letter."

Benjamin Jackendoff, another Los Angeles film producer who recently worked with director Larry Cohen on "Phone Booth," is also intrigued by Duston's story, which he said he read about as a college literature student and recently in a newspaper account of her re-emergence as a controversial figure in Haverhill.

"Her story is every parent's worst nightmare," Jackendoff said. "She's a strong, complex and ambiguous character. That lends itself to a narrative that combines the very different versions of her story from Cotton Mather and the Abenaki. After working with Larry Cohen, you can't help but see the commercial potential for a thriller in a story like that."

In a version of the story by the Abenaki tribe, Duston is more blood-thirsty murderess and less victim. In the Abenaki account, she befriended members of the tribe, got several of them drunk and then slaughtered them with a hatchet as they slept.

In the Colonial version, Duston returned home to Haverhill in a canoe, and the government rewarded her with 50 pounds sterling and other gifts. In 1879, she became the first woman in America to be immortalized with a statue, and her story was told in accounts by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Cotton Mather and Henry David Thoreau. Although she is the heroine of several books, she has yet to be portrayed in a movie.

Interest in Duston's story and her past were rekindled recently when she was made official ambassador of this Saturday's battle of the bands organized by Team Haverhill and the city. Posters of Duston holding an electric guitar, in place of the axe she wields in her Main Street statue, have been hung throughout the city.

Media accounts of Duston and Haverhill have appeared in newspapers across the country since The Eagle-Tribune published a story Friday about the city's use of Duston as a symbol of its downtown revival.

"It's the ultimate feminist story," said Rebecca Day, a Massachusetts native and freelance writer who has done script development for Hallmark Entertainment and Lifetime Television. "It has all the qualities of a hot Lifetime movie. I would pitch it as 'Ransom' meets 'The Crucible.'"

Day said she is particularly intrigued by Duston's psychological makeup.

"What interests me is exploring what made her tick," Day said. "I think the story perfectly illustrates what happens when one's world turns into chaos. A person really has to go into survival mode, regardless of what role society thinks he or she is supposed to play. Although women at this time were considered second-class citizens, I think it's funny how many men so easily became her followers and admirers."

Constantine Valhouli, principal of a Bradford company that specializes in revitalizing historic urban centers and who is helping to promote the music festival, said he has spoken to representatives from New York and Los Angeles production houses about Duston.

"Hannah's story would make a good film for the same reason she makes a great symbol for Haverhill," Valhouli said. "Her story of courage and conflict is timeless. Change the details slightly and it is still happening around the world."

Day, the Los Angeles producer, said he believes Duston's story could be produced on a reasonable budget and still connect with audiences.

"The biggest issue that films like this will face is that period films are often expensive to produce," he said, noting that the most recent film of the genre, "The New World," was a critical disappointment. On the other hand, "Dances with Wolves" grossed over $424 million, and "Last of the Mohicans" made over $100 million, he said.

Shawn Regan writes for The Eagle-Tribune in North Andover, Mass.

Published: August 27, 2006 12:00 am

Proposed Hannah Duston Day appalls American Indian leaders

By Brad Perriello

Eagle-Tribune

HAVERHILL — Leaders of the Abenaki Nation say they are appalled at a proposal to declare an official Hannah Duston Day in the city as a way to generate publicity for Haverhill, saying the idea is racist, perpetuates the Duston legend and glorifies violence.

Duston made history in 1697 when she escaped from Abenaki Indians who had kidnapped her and killed her infant daughter by bashing the child's head against a tree. Duston escaped from an island in the middle of the Merrimack River near Concord, N.H., two weeks later by killing and scalping as many as 10 of her captors.

Posters advertising yesterday's "Haverhill Rocks!" music festival contained the image of her statue holding an electric guitar. The posters sparked controversy and curiosity in recent weeks — so much so that the concert's promoters proposed Haverhill declare an official Hannah Duston Day.

Chief Nancy Lyons of the Coasek tribe of the traditional Abenaki Nation, said using Duston as a promotional tool not only insults American Indians but glorifies violence.

"It's not so much because Hannah Duston killed Indians. The biggest issue that I find absolutely appalling is that the promotion that they're doing is extremely racist — it's emphasizing violence and they're promoting that to young people," Lyons said. "More than being an Indian, being a mother I find it absolutely appalling that a community would promote violence and a violent act in a racist manner to young people today."

Charles True, speaker of the Abenaki Nation of New Hampshire, said Duston has become a folk legend over the years and her legend bears little resemblance to the actual events of 1697.

"Folk legends rarely represent the actual truth about things," True said. "In New England history books, our people have not had a fair shake. We were victimized very cruelly by New England people. ... It makes you wonder why history books for schoolchildren over the years have made us out to be blood-thirsty savages. Haverhill can do what it pleases with its folk hero. We're not interested."

Constantine Valhouli, principal of a Bradford company that specializes in revitalizing historical urban centers, helped promote yesterday's music festival and is a proponent of declaring an official Hannah Duston Day in Haverhill. Valhouli said he envisions the day as a chance for the city to learn about its history with an eye to reconciling the settlers' version of the Duston story with the Abenaki view of her legacy.

"If we do this right, we actually have a chance to really explore how history is interpreted without drawing any value judgments," Valhouli said. "Haverhill's Colonial history might be best explored as a way for future generations to really learn. It's a teaching tool. If we approach it that way, Haverhill becomes a place where tolerance is increased."

Margaret Bruchak, an Abenaki historian, said in order to properly understand the Duston story, it's important to understand the Abenaki culture's view of combat and captivity.

"The whole point of taking a captive was to then transport that person safely. For the whole of that journey they were treated like family," Bruchak said. "When captives were taken, they were almost immediately handed off from the warriors to individuals who would then look after them. Hannah, we know for a fact, was handed over to an extended family group of two adult men, three women, seven children and one white child."

That's why the Abenaki viewed Duston's actions after she escaped with such horror, she said.

"It's almost like the Geneva Conventions, when you think about it. Hannah betrayed the Abenaki Geneva Conventions. It wasn't while she was in the midst of warfare that she did these supposedly brave acts. It was while she was in the care of a family," Bruchak said. "If she had merely escaped, there probably would be very little story to tell, but the fact that she escaped, then stopped and went back to collect scalps — the bloody-mindedness of it is really quite remarkable. ...

"She became a hero because of it. The Colonial Puritan society which saw the killing of white children as an unpardonable sin that required the death penalty saw the killing of Indian children as a glorious act that turns someone into a hero," she said.

The decision to declare an official Hannah Duston Day rests with Mayor James Fiorentini, who did not return calls seeking comment.

BOX: According to historical accounts:

* On March 15, 1697, Hannah Duston and some 39 settlers in Haverhill were attacked by the Abenaki Indians. The Indians kidnapped Duston and killed her baby daughter by bashing the child's head against a tree. About a half-dozen local homes were burned in the raid.

* Duston was held with several others on an island at the confluence of the Merrimack and Contoocook rivers near Concord, N.H. Duston was with her nursemaid, Mary Neff, and a boy named Samuel Leonardson, who had been captured in Worcester the year before.

* On the night of March 30, the trio escaped. Before leaving, they killed and scalped 10 Indians (men, women and children) as they slept, using hatchets they had stolen from the Indians. They scuttled all the canoes except one, which they used to paddle downriver through the night.

* An American Indian woman and boy who escaped Duston's hatchet alerted another Indian party to her escape. But by that time, Duston was headed back to Haverhill.

* At daybreak, the trio spent the first day in Nashua; then the next night they paddled to Haverhill. Duston recognized Bradley's Mill on the Merrimack River, where there is now a millstone commemorating the spot where the three landed.

* Upon her return, Duston received 50 pounds from a government official in charge of the province for the Indian scalps, plus "gifts and congratulations from private friends," according to "The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts" by George Wingate Chase.

* Duston is believed to be the first woman in U.S. history to have a statue erected in her honor — in 1879 in a park near Main Street. Her story has been immortalized in accounts by famous authors such as Cotton Mather and Henry David Thoreau.

Modern tellings leave out Hannah Dustin's heroism

By David A. Dustin

For the Monitor

August 29. 2006 8:00AM

It is always tempting to view history through a contemporary lens. Your article on Hannah Dustin, who survived a bloody Abenaki Indian attack on Haverhill, Mass., in 1697, contained comments that confirm how easy it is to yield to that temptation ("Boscawen scalping inspires town,"Monitor, Aug. 19).

The setting was King Philip's War, a savage episode in the long-running French and Indian wars, which pitted the French and Native American allies against the English in North America. The colonial version of Dustin's story, so-called by Associated Press reporter Jay Lindsay, was documented in contemporary interviews with Hannah Dustin conducted by no less a Massachusetts Colony luminary than the Rev. Cotton Mather.

In his 1702 history of New England, Mather recounted how Dustin, who was 39, and Mary Neff, her 50-year-old midwife, were captured in a raid on the outskirts of Haverhill in which 39 English settlers were killed or taken up the Merrimack Valley. Dustin's husband and seven of their children narrowly escaped the raid, but her week-old infant daughter, Martha, was smashed against a tree before her eyes. The other English captives were tomahawked by the Abenakis.

Soon, the only survivors were Dustin Neff, and 14-year-old Samuel Leonardson of Worcester, who had been enslaved by the Indians for 18 months and spoke a little of their language.

The Merrimack Valley in 1697 was largely unpopulated by English people north of present-day Nashua, and the women were told by their captors that they were being taken to an Abenaki rendezvous somewhere beyond what is now Boscawen. There they would be stripped, forced to run the gantlet and enslaved.

With that fate in sight, these two frightened women and a boy boldly seized an opportunity to slay their sleeping captors where the Merrimack meets the Contoocook. Then they paddled down the Merrimack from Boscawen to the first English cabin they saw — in Dunstable, now Nashua, before stopping the next night.

For some, the fact that Dustin, Neff and Leonardson killed all but one of their captors (who included women and children) at close range with tomahawks, the weapons available, seems to call their morality into question in an era in which Americans prefer their killing executed more impersonally by laser-guided bombs and automatic weapons.

And the fact that these two English women actually scalped their victims today appears barbaric instead of prudent in light of the practice of paying a bounty for Native American scalps (originally set at 50 pounds) in a colony engaged in a vicious and bloody fight for existence.

Was there an element of revenge in Dustin's actions? More than likely. It is a comprehensible motivation for any mother who has just watched her captors slaughter her baby and nearly 40 neighbors on the way from Haverhill.

But it is absurd to suggest, as does the Abenaki representative quoted in your article, that the escapees in this unprecedented historical event were therefore not heroic. Two English women and a teenager were victimized by horrific Native American attacks. Alone in a hostile environment, they were forced to make wrenching life-or-death decisions to survive an experience inconceivable to those of us who live here tranquilly 309 years later and regard the Merrimack and Contoocook Rivers merely as picturesque recreational opportunities as we whiz by in our SUVs.

Rob's comment

The Indians had a valid religious/cultural reason for scalping. They weren't doing it simply because they were too barbaric to know any better. Yet we consider them savages and people like Hannah Duston heroes. That's stereotypical.

David A. Dustin undoubtedly is trying to protect the reputation of an ancestor. But since when have brutality, greed, and revenge—the three motives he attributes to Duston—been synonymous with "heroic"? Never, that's when.

Duston's motives may be comprehensible, but they're also villainous. When you go back and execute your captors in cold blood, it's called murder, not heroism.

A correspondent e-mailed a note about David Dustin's essay:

Am googling around to learn more about Haverhill, and raid in 1697. Am a descendent of Samuel Gill whom I believe was taken in the same raid as Hannah Duston.

Response to David Dustin:

You are right, we can never know what goes through anyone else's mind, the horror and fear. That is a tragedy. And we don't really have her own story from her own mouth, it was probably written down by Mather.

It is my current understanding, although I am always reading and learning new things, that there were other survivors, Samuel Gill being one of them. He was 10. Haverhill is near to Salem, Mass. and was the site of the, or some of the, Salem witch trials. I am not a fan of Cotton Mather, so that argument of his integrity does not carry weight with me, but that is me.

Samuel Gill's story is a completely different one. He was taken to St. Francis and adopted, I don't know by which Indian family. His father went to Quebec twice to try to persuade him to return (he was allowed to return home if he wanted) but he preferred to stay with his new Indian family. He married another captive and their children also stayed at St. Francis and married natives. This story is well known, and recorded in many histories and narratives.

I wondered why he would stay. I would suspect that maybe things were not so sweet in Haverhill. But so far, again, I can only speculate and read histories of both sides and we will never know his mind.

Anyway, it gives one pause.

Jane Barber

Brooklyn, NY

More on Hannah Duston

Shops bobble Duston controversy

Native-themed bobbleheads

Related links

Scalping, torture, and mutilation by Indians

Savage Indians

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.