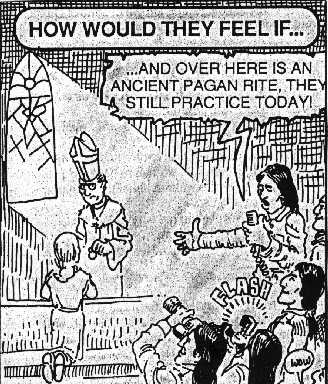

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Another Stereotype of the Month entry:

Fear of Thanksgiving! Who and Why? Mohawk Students Protest Ban of Philosophy.

School authorities are calling it a religion

MNN. May 25, 2005. Wampum 7 of the Kaienerekowa/Great Law of Peace, the Constitution of the Kanienkehaka/Mohawk, provides that the "ohenton kariwatek:wen", the opening thanksgiving, shall be recited at every gathering of the people. It means "the words that come before every matter". Every day we give thanks to all Creation that helps human life. We thank the Kasatstenera:kowa sa'oiera, the great natural power, for producing these.

The "ohenton kariwatekwen" is a philosophy, not a religion. It is a form of consensus making that starts before any meeting or activity. The addresser is responded to by the addressees with "henh" meaning "Yes, it's true". We place ourselves within an interdependent system of relationships of all elements of the natural world which are all alive and equal, not above or beneath anything. We thank the earth, water, animals, people and Creation. The natural world is our family and we respect all our relatives.

An elder explained, "Creation is perfect with all forces and facilities necessary to help the people". The natural world is the perfect reality. Our constitution, the Great Law of Peace, is based on this reality. Once that consensus is agreed upon, we realize that there are things greater than our conceptions or grievances. We do not pray or ask for things because the natural world has provided everything that we need to live. We are taught to face reality and to give thanks. That is why we must take care of the environment and our relationships for our future generations.

We do not accept that we are a minority on our own homeland. The Europeans invaded and occupy our territory. They have become the majority. According to international law we have a right to learn our languages and history and teach them to our chidlren. We must also teach the majority about our history from our own perspective. As American schools are on Onkwehonwe/Indigenous land, we have an obligation to teach them the "ohenton kariwatekwen". The United States thinks it's above international law. The judges refuse to respect it and school principles do the same. Americans instead are trying to extinguish those elements that are contrary to their hierarchical ideology in which they co-modify every living thing and put a dollar value on it.

The whole story is told in one brilliant scene. On Monday, May 23rd, Glen Bellinger, superintendent of Salmon River Central School, Fort Covington, New York State, suspended some Mohawk students. Around 60 % of the students in this non-native school are Mohawks from nearby Akwesasne. For the past three years the Mohawk students have recited the "ohenton kariwatekwen" over the school loudspeaker. Suddenly it was decided to interpret this philosophy as a prayer, which, they say, violates the constitutional separation of church and state.

The students retorted that they are pledging allegiance to the circle of life while the non-natives are pledging allegiance to the U.S. Government and the flag. We Mohawks have our own constitution and government. Giving thanks to the natural world goes back thousands of years. Pledging allegiance to the flag is recent. It was not part of the original U.S. Constitution. The practice was added in the late 1800's.

The school authorities refused to allow the Mohawk youth to use the public address system. They told them to go into the gym and say their "prayer". The youth went there and completed the "ohenton karewatekwen". Most went off to their classes. About 40 remained in the gym. The authorities turned the lights off and left the students in complete darkness. Parents and Great Law Longhouse people arrived. After discussions, ten students would not budge. They could not compromise the "ohenton kariwatekwen" and were suspended.

There is nothing more metaphorical than what they did to these young people. What does this act of turning the lights off mean? Instead of celebrating their brave action, the school authorities feared the intelligence of the Mohawk youth. They cannot understand how a social order can be maintained when humans are treated equally. This is a political movement of consequence linked to this concept of equality. The establishment in maintaining their global mono culture must have similarity of language, belief and ideology across the globe, controlled from the top.

The opening address says it all. It defines who we are and where we are. Their hysterical reaction did not quiet the youth. The youth were trying to remind them about the perfect reality of the natural world which has a momentum of its own. To shut down the lights in the gym and to try to cast the children into darkness cannot stop the natural world. It is a weak action by those who live in darkness, the darkness of their minds and souls. They are trying to put out the flame, the voice of these young people. But they can't.

Why were the colonizers afraid? In their confusion they tried to control the light inside the children who were defending the way of life, the culture and the language. The newcomers to our land have been trying to kill our fire, our voice, ever since they arrived. They sense it is glowing in our children today who are the progenitors of our nation.

Our children are not in the dark. The Indigenous people have seen it coming for a long time, that all humans must make the journey back to nature. Our children are starting the journey.

The actions of the children frightens them. They are reacting by attacking the "ohenton karwatekwen". They think if they stop the children they can continue to try to control the environment and the world.

As an elder said, "Our people keep wanting to send our kids to white schools. We have to create our own schools instead of mimicking the outsiders who have abused us and our children". Education has always been used as a weapon, as a tool of indoctrination of people into their foreign culture. Today they cannot force Christian religion and doctrines down our throats. But they will try with any kind of excuse.

The pattern is shifting to what is real. Everything will be played out. Those who have been raised on the "ohenton kariwatekwen" will be able to see the big picture. On Thursday, May 26th, 150 students protested in the school gym. Five of the 6th grade students were suspended.

(For comments and updates call 518-358-6012)

Kahentinetha Horn

MNN Mohawk Nation News

Thanksgiving Address and the Pledge of Allegiance

Posted: October 06, 2005

by: Editors Report / Indian Country Today

The flare-up was predictable. Most tellingly it sprung up at Akwesasne, Mohawk land, where the beacon light of Indian consciousness has flashed before.

The board of education that oversees the 65-percent-Mohawk Salmon River High School banned from its total school system an established morning ritual: the recitation of the Haudenosaunee (Mohawk) Thanksgiving Address, or "the words that come before all else." This blow to Mohawk pride and identity caused quite a stir in the Akwesasne community, bringing to the fore important questions of Native cultural existence in North America.

For local reporters, a sense of wonderment is expressed that a controversy for once has arisen between Mohawks and a segment of the local white establishment not involving gaming, land claims or contraband. This time the issue is over a deeply-felt and these days more often-heard traditional oration, one that is best given in the ancient language which, at Akwesasne, many people -- particularly older adults -- speak and understand.

As in all things Mohawk, the expression of the sovereign Indian culture is at the forefront. Salmon River High School, for instance, flies three flags at the same height: Mohawk, American and Canadian. The Mohawks have fought hard to establish respect for their tribal sovereignty and cultural heritage.

Established as a Jesuit-controlled village, Akwesasne (St. Regis Parish), Catholicism on the Mohawk reservation was particularly harsh against practitioners in the longhouse traditional ceremonies. Yet the ancient practices survived; and as the younger generations graduated from college while elders still conducted ceremonies, community consciousness about the ancient culture forced the teaching of language, history and other Native studies topics in the local curriculum.

On the same reservation, the Akwesasne Freedom School conducts a successful Mohawk language immersion curriculum. The Thanksgiving Address, as recited in Mohawk, is a centerpiece of the introduction and study of the language there.

Conducted for more than three years, the community and students had come to expect the recitation each Monday morning. As the message of the Thanksgiving Address is completely positive and humanistic while "addressing" higher beings, the Mohawks were proud to share it with students from the local non-Indian families, and the hard-won right to be represented and understood in the public sphere was enhanced.

The decision to deny the recitation of the address hit many Mohawks as needless hostility. A school board member had complained that the address, which mentions and gives thanks to a "Creator," violated the separation of church and state. The board quickly banned the recitation out of hand.

Several hundred Mohawk students conducted rallies and civil protest against the decision while the board denied any redress. Five sixth-graders were suspended. Things got a bit hot. Mohawk families sued, arguing that a reference to a "Creator" does not define the address as a prayer. This hard-to-make argument reflects the fervor of the moment in the continuous search for respect as tribal cultures.

Various definitions of prayer have, of course, arisen. The school board itself opted to consult Webster's Dictionary, while Mohawk commentators wonder why they did not consult the elder culture specialists in their community. "There is no word for 'prayer' in our traditional language," one parent told National Public Radio.

A clarifying argument focused on the Pledge of Allegiance, with its unambiguous reference to a country "under God." What makes the Pledge of Allegiance so sacrosanct, when a Mohawk cultural expression cannot be held to be less unifying or humanistic? The pledge, community activists pointed out, started out without referring to a "God," and was proclaimed in 1892 to celebrate the Columbus 400th Anniversary bash of the time. Only in 1954 were the words "under God" added in.

This interesting history is enough to lighten the discussion, except the Mohawks are serious about their culture and its representation in education: and the Thanksgiving Address is as central to the ancient culture as anything one can find. Mohawk Chief James Ransom credits the strength of traditional culture with his community's high rating for college-level students.

While Ransom approached the matter with diplomacy, an Albany reporter cut to the chase. "It's essentially about two different world views -- the Mohawk's spirituality and the culture of white, Christian America ... [and] ... the affair has brought to the surface what Mohawks say are centuries-old efforts by a dominant European society to obliterate the American Indians' way of thinking." ("A test of Mohawk spirituality, God, law: Tribal members contest school ban on traditional ritual, seek to halt Pledge of Allegiance" by Rick Karlin, Albany Times-Union, Sept. 25.)

Some compromises are being heard now. The Salmon River schools have offered a more private space for Mohawks and others. The legal matter persists. It is an interesting case and reflects the Mohawk proclivity for focusing issues that will widen across society.

As the Bush administration gleefully pushes the challenge to science from creation-based sources, the assumption is that this reflects only the biblical creation. Well, other peoples, among them traditional Native practitioners and believers, have creation stories too. The variety of creation and thanksgiving ceremonial traditions among Native peoples can no doubt represent the widest imaginable rainbow of possibilities, if the challenge is there to explain the spiritual nature of the universe according to our own cultural traditions.

If the Pledge of Allegiance, complete with its reference to the Christian deity, must be allowed in America's schools, so too must the ancient Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address be allowed its reference to the longhouse deity. Consistency of application of constitutional principles and interpretations regarding the separation of church and state would suggest, it seems obvious to us, either they both stay in or are both cast out of the classroom.

Nobody denigrates here the Pledge of Allegiance -- the recent 100-year-old statement of commitment means a great deal to many people -- but there is nothing like the strength of a truly ancient expression of human connection to the natural world as represented by this central Haudenosaunee oration. The Thanksgiving Address, fixing the mind of the human being in the context of the wondrous forces of nature that surround us and sustain us, is at once mystical and deeply truthful. Beyond this particular controversy, we submit, it deserves deep and abiding contemplation.

© 1998 -- 2005 Indian Country Today. All Rights Reserved

By: Denise Raymo

Staff Writer

September 05, 2006

AKWESASNE — To avoid further legal action, a compromise may be worked out over the reading of a Native American passage in Salmon River Central School District.

The Thanksgiving Address had been heard, along with daily announcements and the Pledge of Allegiance, at both Salmon River High School and at the St. Regis Mohawk School, where the student body is exclusively Native American.

But, following a complaint last spring, School Board members banned the reading on the advice of school attorneys, who said the passage constitutes a prayer.

About 60 percent of the district's students belong to the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, and many staged sit-ins last year to protest the School Board's actions.

They say the address is a cultural expression, not a prayer. They have no choice but to listen to the Pledge of Allegiance each day, they say, so hearing the address should be no different.

A compromise was reached at the end of last school year where the address was recited mornings and afternoons on Mondays and Fridays in the auditorium for those who wanted to hear it.

But some Native students felt having to leave their assigned class to go to the auditorium drew unnecessary, negative attention to them and emphasized cultural differences in school.

The passage is what the people of the Iroquois Nation speak at the opening and closing of gatherings to balance the hearts and minds of people with nature.

A federal lawsuit was filed on behalf of four students who claim their cultural expression is being suppressed.

Representatives on both sides of the issue recently appeared in court in Syracuse and were encouraged to find a resolution before the case goes to U.S District Court in Binghamton on Dec. 4.

"We're just trying to work out an agreement before this all has to go to court," said School District Superintendent Glenn Bellinger. "We're doing a lot of thinking between now and the next board meeting."

Monday, Sept. 11, will be the next meeting of the full School Board, where some guidance will come from the members.

"The board's mission is to come up with something — anything — that will give direction for a group of people to get together and solve this," he said.

Bellinger is not sure who will be involved in those talks, "but I, as an administrator, can't solve it. Lawyers can't solve it. It's got to be the people. Let the people come up with something."

Numerous attempts by the Press-Republican to reach families involved in the lawsuit were unsuccessful.

Rob's comment

On the one hand, you could say that thanking the "great natural power" is at least quasi-religious. If this "power" isn't equivalent to random acts of physics and chemistry—i.e., nature—it must be supernatural in some way. That makes it religious by definition.

The talk of something "producing" something else reinforces the idea of a "power." In a typical Native worldview, rocks, rivers, and trees didn't create themselves. That would be the rational or scientific viewpoint. Rather, a typical Native would say a separate entity, a Creator, created them.

Thanking "Creation" is one thing, but thanking the Creator is something else. It would be easy to confuse the two and conclude the students were saying a prayer. And even endorsing the abstract notion of a Creator is an affront to the First Amendment. Think of all the atheist children who don't believe in God or religion, period.

On the other hand, it's common for people (including Native people) to say every aspect of Native life is religious or spiritual. In other words, that there's no divide between the religious and the secular in Native thinking. While there may be some truth to this, many Indians today are not spiritually inclined. And of those that are, not every aspect of their life has spiritual overtones. When they bite their fingernails, vacuum the carpet, or fill out their tax forms, I doubt they're thanking Creation or the Creator.

In effect we have a dual stereotype here. And ironically, the roles are reversed. The non-Indians are claiming that everything the Mohawk students say has religious meaning. The Indians are claiming the Mohawk students are just like everyone else, with a philosophy that lacks religious meaning. As usual, the truth is probably somewhere in-between.

More on the story

Mohawk blessing = prayer

Related links

"Primitive" Indian religion

Hercules vs. Coyote: Native and Euro-American beliefs

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.