To begin, some thoughts on how silly our cartoon-style media violence is. From the LA Times, 9/25/01:

To begin, some thoughts on how silly our cartoon-style media violence is. From the LA Times, 9/25/01: To begin, some thoughts on how silly our cartoon-style media violence is. From the LA Times, 9/25/01:

To begin, some thoughts on how silly our cartoon-style media violence is. From the LA Times, 9/25/01:

COUNTERPUNCH

'Our' Violence Versus 'Theirs'

By RAY GREENE

Ray Greene is a Los Angeles-based author and documentary filmmaker. His book "Hollywood Migraine" will be released Oct. 22 by Independent Publishing Group.

It is the great cliche, bad-movie shot of our time. Two men of different races are running like Olympic track stars through the beveled glass doors of an urban foyer. Behind them, an enormous, soulless office tower glowers impassively. It could be day, it could be night. We might be in Los Angeles or New York or maybe Chicago. Location is irrelevant. Predicament is all.

And so they run, these two men we'll call Gibson and Glover, or maybe Tucker and Chan, looking frightened but never panic-stricken—scared but heroic all the same. At each step, time itself seems to conspire against them. They move in the freeze-frame, slow-motion agony of nightmare.

And then, at the precise moment when it would be logical for these running men either to escape or to be engulfed, a gigantic explosion rips through the skyscraper behind them, transforming it into a fiery monster, a dragon of architecture, belching concrete and mortar, steel and glass. This shot, repeated endlessly in sometimes imaginative variations, is one of the things that drove me out of movie criticism at the close of the 1990s, after a decade-long run. In the past 15 years or so, thanks in part to the computer-effects revolution but mostly to the desire of our movie producers to appeal to their own degraded notions of teenage boys and the insatiable foreign action market, our culture has marinated in mindless, epic violence. In testosterone, to give it a name.

You know the roll call: "Lethal Weapon" and "Die Hard." "The Rock." "The Matrix." "Mission: Impossible." "Face/Off." "Con Air." Each vigilante plot line so disposable it is almost impossible to remember a half-hour after the end title rolls by, but functioning according to a received set of values, including the idea that there is good violence and bad violence. And that here in America, our violence is good violence because it has come from us.

What happened at the World Trade Center was not good violence by anybody's standard of measurement. Though vigilante in spirit—for what is a vigilante if not someone who takes some highly personal and idiosyncratic notion of cosmic justice into his or her own hands?—it was "their" violence, not ours. And it was violence with consequences, something rarely dramatized in the exploding funhouse of American movie culture. Violence with anguished aftereffects, seen in the faces of people who could have been any of us as they walked from makeshift hospital to makeshift hospital, or waited by the phone, wan masks of disbelief, trying to find out if the people they came home to, or went to movies with, were still alive.

A few years back, a massively successful film called "Independence Day" was marketed to the world in print ads and trailers with an image of the White House detonating like a cherry bomb. It was an arresting visual effect, well executed from a technical standpoint and, like most of what we see on TV and in movie houses, meant to be nothing more than good, clean fun. We know now how nearly that image managed to come to life a few days back, and we can speculate as to the even wider political ramifications of the moment if it had.

Instead, the executive branch is still going about its business, which is mainly the work of reacting to the fantasy stuff of recent American action films brought to horrifying life.

Meanwhile, studio executives scurry to adjust their release schedules like cockroaches caught in the hot fireball reality of our current moment. Fantasy is carefully sealed off from reality, as TV executives paint the twin towers out of shows set in New York, then run them against news programs still crammed with a thousand angles of death at ground zero. Blockbuster films such as "Spider Man" and "Men in Black 2" rethink, revise and reshoot their New York endings, while the remaining "terror plot" formula films are suddenly as devalued as a bad stock.

On AM radio, that other bastion of disgruntled masculinity, the airwaves resonate with cries for indiscriminate vengeance. Harsh, squawk-box voices advocate apocalypse of the thermonuclear and petrochemical varieties. We are all trapped inside a real-world "Die Hard" script, while the braying chorus of the shock-jock bully boys demands that we entertain as serious solutions the self-righteous codes of conduct proposed by our movies and TV.

As immediate shock has given way to wholly justified outrage, their cry has begun a fitful and uncharacteristic migration to more reputable and less exclusionary outlets. To newspapers of record and network TV. It is the cry of "our" violence, which is always appropriate and moral, against "their" violence, which is categorically without motivation and insane. A cry of thunder and blood. Redemption and purgation. And firepower, always firepower.

And testosterone.

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

Next, some thoughts on how this media violence should change. From the LA Times, 9/18/01:

THE BIG PICTURE

The Time to Get Serious Has Come

By PATRICK GOLDSTEIN

If there's one place where the carnage at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon must have inspired some uncomfortable self-reflection last week, it was in the executive corridors of this town's studio conglomerates. Summer after summer they have churned out eerily similar fantasy images of planes being hijacked, buildings being blown-up and cities being reduced to rubble—all under the guise of popular entertainment.

Much has been written in the past days about the terrorist attacks' effect on our political and financial institutions. But little has been said about the effect on our pop culture. Yet I suspect that our culture will eventually be transformed as much as any other arena of American life. "When you drop a stone in a pond, it has a ripple effect," says Armyan Bernstein, producer of such films as "13 Days" and "Hurricane." "Well, this is like dropping a boulder or a meteor. I don't know one person who hasn't had their spirit challenged. People have been changed."

Change is overdue. In the past decade, Hollywood has metamorphosed into a soulless popcorn machine, creating mindless dreck designed to pay off at every stop on the global gravy train, from movie theaters to cable TV to DVDs. The studios have largely abandoned any pretense of grappling with real-life issues of the modern world. Ask any top screenwriter or producer: It's almost a lost cause to pitch a studio an adult drama or a movie about politics. Unless you've got an A-list movie star in your back pocket—or a project helmed by a director with the pile driver ferocity of an Oliver Stone or Michael Mann—they won't even stamp your parking ticket on the way out. For every "Erin Brockovich" or "Traffic," there are hundreds of forgettable fantasy thrill rides like "Tomb Raider" or "The Mummy Returns." If you want to see drama about contemporary issues, you have to turn on your TV and watch "The West Wing" or "Law & Order" or "The District." The movie studios these days are in the celluloid theme-park business.

Hollywood executives argue that they simply make the movies people want to see. So maybe Hollywood will recognize that Americans suddenly view the world as a more serious place. There's a new moral gravity out there. It is a time for soul searching. In Washington, politicians are putting aside petty partisan differences. In hard-boiled New York, there has been an outpouring of good Samaritanism and communal feeling.

The terrorist attacks may have brought to a close a decade of enormous frivolity and escapism. No one knows for sure how quickly or enduringly this kind of transformation takes place. Pop culture is largely a province of the subconscious. That's why it's so unpredictable, why it's so hard to tell which movie or CD or TV show will be hit or a flop.

But for years to come, many of us will feel a tiny shiver when we see a bearded Middle Easterner getting on a plane in front of us. So imagine our subconscious reaction to watching a movie where a building full of people is incinerated by a fiery explosion. Will it still feel like "fun"? Will it still be "exciting"? Will studio marketers still cheeringly call it a "spine-tingling thrill ride"?

*

Hollywood has always been thought of as a pretty silly place, intoxicated by ego and vanity, but in the past, when faced with tragedy, it has sobered up fast. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, fatuity turned to patriotic fervor overnight.

James Stewart put on enough weight so he could pass an Army physical and enlisted as a private—he ended up a bomber pilot. William Holden, using his real name, became Army private William F. Beedle Jr. Robert Montgomery joined the Navy and eventually commanded a destroyer during the Normandy invasion. Directors like John Ford, John Huston and William Wyler went off to war and made combat documentaries, often in life-threatening situations.

After Henry Fonda finished shooting "The Ox-Bow Incident," he enlisted as a sailor, even though he was 37, with three children. He got as far as San Diego before 20th Century Fox studio chief Darryl Zanuck had the shore patrol send him back to Los Angeles, where Zanuck put him in a film for the war effort. Everyone started shooting war movies, even though the amount of film available was cut by 25% because the military needed cellulose to make explosives.

Soon Hollywood was making so many war-in-the-Pacific films that the studios ran out of bad guys, since in the hysteria after Pearl Harbor, the government had rounded up all Japanese American citizens and put them in internment camps. The studios would have to make do with hastily recruited Chinese actors instead.

So far, today's entertainment giants have reacted to the tragic events with largely cosmetic measures. A few scripts are being tossed out or rewritten. Warner Bros. has postponed the release of "Collateral Damage," which opens with a terrorist explosion, while Disney has pulled "Big Trouble," which features dimwitted criminals hijacking a plane armed with a nuclear weapon. The studios obviously fear that the public will turn away in distaste, especially now that reality is all too interchangeable with special effects.

But how long will our unease last? How would you react today to watching hijackers seize the president's plane in "Air Force One"? Or mercenaries holding an airport hostage in "Die Hard 2"? Or scenes of the White House exploding in "Independence Day"? Will it will be too close for comfort to watch this weekend? What about next month or next year? When will gore and mayhem and gung-ho bravado be an acceptable escapist fantasy again?

Zanuck found himself pondering a similar question when he came back from World War II and the Army Signal Corps. As Otto Friedrich writes in "City of Nets," his study of 1940s Hollywood, Zanuck realized that the war had subtly changed America's attitudes about itself. Audiences wanted something different from the cheap westerns and detective stories that had helped keep Hollywood afloat during the Depression-era 1930s.

"When the boys come home, you will find they have changed," Zanuck told his production staff. "They have learned in Europe and the Far East. How other people live. How politics can change lives.... I recognize there'll always be a market for Betty Grable and Lana Turner and all that [breast] stuff. But they're coming back with new thoughts, new ideas, new hungers.

"We've got to start making movies that entertain, but at the same match the new climate of the times."

*

Zanuck followed his instincts by making a string of socially conscious hits, including "The Razor's Edge," "Twelve O'Clock High" and "Gentleman's Agreement," which won the Oscar for best picture in 1947. Willy Wyler came back from the war and made "The Best Years of Our Lives," which won the Oscar in 1946. It wasn't just the prestige pictures that sketched a darker, more unsentimental view of the world. The disillusionment and uncertainty of postwar America also spawned a flood of crime thrillers that were so gloomy they became known as film noirs—movies like "The Big Sleep," "The Killers," "Out of the Past," "The Naked City" and "Force of Evil." The titles alone tell you what sort of pessimistic tone they had.

It wasn't the only time filmmakers responded to a new audience mood. It now seems clear that the flowering of American film in the late 1960s and early '70s—the era that produced everything from "Bonnie and Clyde" and "Midnight Cowboy" and "MASH" to "Chinatown" and "The Godfather"—was largely inspired by the tumult of late-'60s anti-Vietnam protests and political assassinations.

Has the suffering we've seen in the past days on TV put a new chill in our lives? We really don't know—it often takes years before anyone can make sense of seismic cultural changes. Obviously some sort of normality will return: Jay Leno will tell jokes again. Britney Spears will be back on MTV. Kids will go see "Monsters Inc." But there is a new whiff of melancholy in the air. And our most gifted artists, be they filmmakers or songwriters or poets or painters, will be the first ones to catch the scent. Touched by some tiny spark from this tragedy, they will be the ones to transform our communal sorrow into something that moves us or makes us laugh again.

Art is the community's medicine. As Saul Bellow once wrote: "The artist must be a prophet, not in the sense that he foretells things to come, but that he tells the audience, at the risk of their displeasure, the secrets of their own hearts."

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

Another column makes similar points: how purposeful movies can enlighten us while frivolous ones distort our view of reality. That applies to comics books also. From the LA Times, 9/18/01:

COMMENTARY

Renewed Respect for Power of Images

Current events are prompting reassessment of many things, including movies. We've learned for sure: visuals linger.

By KENNETH TURAN, TIMES FILM CRITIC

Catastrophes, by their nature, lead to reexamination and reconsideration. Everything looks different after a day like last Tuesday, and it's almost inevitable to question, in the quietest part of yourself, "If this is the kind of world we live in, what am I doing with my life?"

That odd, marginalized feeling—that sense that ordinary concerns and occupations seem trivial and pointless if you are not doing something to alleviate the surrounding chaos—is common at a time like this, but it made itself felt especially strong to me as a film critic. What could be more peripheral, less important to the way things are, than reviewing motion pictures and even, by extension, the frivolous, self-involved movie business itself?

The movies, of course, have not shied away with showing terrorism on the screen. Far from it. Yet in thinking over all the films, excellent or indifferent, from "Die Hard" to "The Siege" to "Passenger 57" and "Air Force One," it's hard not to feel that they let us down, not because they didn't prepare us for the enormity of a terrible reality (they didn't, but that really wasn't their mandate) but because they were counterproductive. For, watching these movies made us feel, erroneously it turned out, that we'd had a whiff of what the real thing would be like. Big-screen terrorism was something good for a rush, something that went well with popcorn, something that happened only in the movies, rather than the dreadful reality of a bottomless sinking feeling that gets deeper every day.

Looking even punier now are the films that actually wanted us to feel sick, films like "The Cell" and "Seven" that delighted in having our skin crawl. They wanted us to squirm as if evil were right in our laps, and now that it is, their posturing seems more childish and despicable than ever.

Despite these misgivings, we have to acknowledge that film and the power of the moving image are central to what we're going through—if nothing else, no one who saw the amateur video of that first jet hitting the first tower will be able to get that picture out of his or her mind.

More than that, if, as the government has suggested, it is Islamic fundamentalists who are behind these acts, the power of the moving image is certainly part of where their fury comes from.

As several columnists have noted, these attacks stem in part from a disgust with the modern world, with the huge and potentially crippling cultural impact our music, our mores and, inevitably, our movies are having on the traditional ways of life these people are committed to preserve at all costs. They see our films as infecting their world, changing their children's attitudes, in ways they find abhorrent.

*

Given all that, what can be said for film in these terrible days? What aspects of the strength and resilience of the medium can we take comfort, even pride in?

Most obviously, even if we don't take advantage of or even like all of it, just the fact that we have such a wide variety of movies as viewing options is a key indicator of the kind of open society we have and want to preserve, something we should not take for granted or consider irrelevant.

Just the ability to go out to the movies, even silly ones, has a value that may not be immediately obvious. When I went to Sarajevo in 1993, to attend a film festival and talk to residents about what film had meant to them during the siege, I was surprised to find how much people had been invested in trying to see movies, even if it meant risking their lives during shelling. "I was scared to death, running all the way with my cousin," one woman said about a clandestine expedition to see, of all things, "Basic Instinct." "It was very dangerous, but we did it."

They did it, said journalist Dzeilana Pecanin, because "in spite of all the hardships, we never gave up on the things that made us human beings, not animals." Because seeing films helped provide what was most denied Sarajevo's citizens, a pedestrian feeling unremarked on during peacetime, the sense of being normal.

"You don't have to have everything fine to want to see movies," Haris Pasovic, who ran the first wartime festival in Sarajevo, told me. "You see them because you want to connect, to communicate from your position on the other side of the moon, to check whether you still belong to the same reality as the rest of the world.

"The favorite question of journalists during my festival was 'Why a film festival during the war?' My answer was 'Why the war during a film festival?' It was the siege that was unusual, not the festival. It was like we didn't have a life before, like our natural state of mind and body was war."

*

The specific content of films can be of exceptional value as well, if we but have the wit to make use of it. For if knowledge is truly power, and if without understanding, no amount of military force can mandate a lasting solution, film can be of enormous use in showing us, from the inside, the nature of the societies and the individuals who are on the other side.

Iran (which has not been implicated in the attack) has the most active film industry of any conservative Islamic country. And though Iranian films can be straitjacketed about the kinds of subject matter they are allowed to address, the best of them, such as Jafar Panahi's "The Circle" and the bicycle race segment of the more recent "The Day I Became a Woman," directed by Marzieh Meshkini (the wife of Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf), vividly illustrate the rigidity and fierce anti-modernity of this type of culture, and do it from the inside.

Even more impressive and valuable is a film hardly anyone chose to see, a small Indian work, made for $50,000 in 16 days by co-writer-director-cinematographer Santosh Sivan. It's called "The Terrorist," but its name tells you only part of why it's so instructive.

The story of a crisis of conscience in the young life of a committed revolutionary suicide bomber, a so-called "thinking bomb," "The Terrorist" takes pains to make the members of the shadowy group it follows sound rational: "Our struggle has a purpose," their leader says calmly and with conviction. "Justice is on our side." The easy, Hollywood way out of painting these people as completely deluded is not to be.

Rather, inspired by the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, one of this film's intentions, which it realizes, is to provide insight into the mindset of people willing and even happy to die as martyrs to a cause. It shows us, as did the chilling interviews with the Palestinian terrorists in the Oscar-winning documentary "One Day in September," how and why otherwise intelligent people are able to think and act the way they do.

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

And an editorial plea for our media to get serious. From the LA Times, 9/24/01:

Shake the Culture Too

With few exceptions, the dreamy comfort of U.S. affluence and the absence of significant national challenges or threats in the last decade saw popular culture magnify some superficial and commercial aspects of American life.

During these recent days of nonstop news, did anyone miss the aggressive advertising or obsession with fame, sex, celebrity and beauty? Does the buzz over cleavage at a canned awards show merit even a sigh now? Or the celebrations of gossip and notoriety, misogyny and violence that pervaded our public chatter as recently as Sept. 10? Having seen the obscenity of real violence, does anyone await more of the staged stuff?

The earnest debate on gravitas that took place during last year's presidential campaign might now be better directed at the larger society. Now, while we're pained and uncomfortable, is the time to reconsider not just airport security but cultural priorities—what we as cultural consumers choose to consume. Pop culture's manufacturers claim they merely provide what we, America's consumers, want. OK, let's redefine what we want. Even mired in the emotional muck of awful death and destruction, we half-expect a boastful 30-minute special explaining how filmmakers accomplished such realistic special effects for our entertainment. We have already seen heroes' images repackaged and fed back to us in quick cuts by advertisers offering a "salute." But those weren't stuntmen on fire falling from the skyscrapers. And we won't see firefighters and office workers stride out of the smoke in slo-mo, soiled but safe, in time for the credits.

Should a pretend "Survivor" still sell once we've survived the real thing? And seen so many genuine innocents who did not?

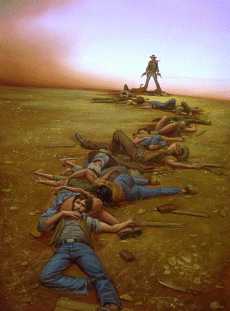

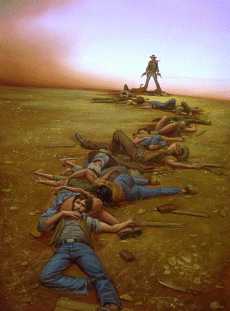

In the long run, post-9/11 popular culture may rise to the creative challenge of describing and interpreting the realities of the less secure, more complex world we now realize we inhabit. This won't be easy. It will require real thought, and less formulaic eye candy of the physical-beauty and exploding-gunpowder varieties. The visual shorthand and perhaps tastes have changed drastically. Will the new era produce a new "All Quiet on the Western Front" or more Green Beret movies?

The mental wounds remain raw, as they will for a while. Late-night hosts will control themselves, at least temporarily, while deciphering what we'll accept as humorous or tasteful. All this will be shaped by the anticipated new "war," whatever that drawn-out struggle will look and feel like.

Many urge a rapid return to normalcy. At least in terms of popular culture, individual Americans may ponder, in light of the pains we've shared, whether the normalcy of recent years is what we really want to return to. Or has the real reality show and its agonizing images perhaps cured our infatuation with shallow fame and hollow shocks?

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

The sad reality

It took 15 years of the Vietnam War before Americans realized their government might not be a paragon of virtue...that all wars were not just...that questioning authority might have value. In that case America acted out of hubris and learned a tragic lesson, like a protagonist in a Greek drama.

In 9/11, the 3,000 people killed had no clearcut connection with America's nationalistic policies. Nor did Americans as a whole understand the link between the terrorist attacks and past policy decisions. It's as if Oedipus hurt himself by letting his dog run away, not by killing his father and marrying his mother. There was a lesson to be learned, but nothing requiring any serious soul-searching.

That explains why Americans returned to normal in a couple months rather than a couple years. A bully bloodied their nose, so they beat up the bully's friend, burned down his house for good measure, and declared themselves revenged. End of story as far as America's concerned.

From the LA Times, 11/13/01:

THE BIG PICTURE

Changed Forever? No, Two Months

By PATRICK GOLDSTEIN

If you drove past 20th Century Fox in October, you might have seen the giant billboard at the entrance to the studio that showed two firemen raising the American flag over the rubble of the World Trade Center.

But the billboard's been painted over—it now touts the Farrelly brothers comedy "Shallow Hal." Last week "Extra" opened with the breathless teaser: "Brad Pitt: Bare Chested and Baring His Soul!" Variety was crammed with tales of Harry Potter mania and Jennifer Lopez casting news. My phone has been ringing off the hook with studio marketers touting their films' Oscar chances while bad-mouthing their rivals' movies.

Whew! Hollywood is back to normal again. Or is it?

Like the news media and Madison Avenue—in fact, like the country itself—the movie industry has been wrestling with a tangle of conflicting currents and mixed messages. People go to movies to escape! Patriotism sells! Go have fun! Be alert for terrorists! Nothing has changed! Everything has changed! Even studio marketing experts, who make a living out of figuring out audience tastes, have had a hard time reading the national mood.

In the wake of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the media made their customary rush to judgment, pronouncing the world of entertainment forever altered, led by Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter's much-quoted proclamation, "I think it's the end of the age of irony."

Movies about terrorism were yanked from studio production slates. "America the Beautiful" was sung everywhere from baseball parks to the Broadway stage of "The Producers." MTV's "Total Request Live" host Carson Daly donned an FDNY cap and the video network aired a celebrity-filled special on the terrorist attacks. The hush of patriotic sobriety hung in the air. Dan Rather held David Letterman's hand and wept. Sly Stallone, Al Pacino and Adam Sandler manned the phones, taking donations during the "America: A Tribute to Heroes" telethon.

After the terrorist attacks, conventional wisdom held that audiences would shun entertainment laden with violence, snarkiness or any other pre-Sept. 11 frivolity. Smart-aleck cynicism was out. Self-searching was in. As it turned out, the country was simply going through a period of national grieving. Innocent people had died, and a war against terrorism had begun. But even mourners eventually get on with their lives. The show must go on. As George Bush said at the end of September: "Get down to Disney World in Florida. Take your families and enjoy life."

In Hollywood, you could almost hear a sigh of relief. (The day after Bush's speech, Michael Eisner sent out a gleeful e-mail to Disney staffers calling the president "our newest cheerleader.") People were going to the movies again. In fact, the fall box-office numbers are significantly over last year's, with the business on track for a record year. Moreover, people are going to exactly the same kind of movies they went to before the terrorist attacks.

Hollywood market research guru Joe Farrell polled moviegoers after the terrorist attacks and found that their movie preferences hadn't changed. Soon the same studios that were postponing terrorist films in September were moving up military films like "Behind Enemy Lines" and "Black Hawk Down." Fox, which made "Behind Enemy Lines," test-screened the film last month to gauge audience receptivity. The movie, which had been tested before Sept. 11, did even better the second time around.

"Training Day," a violent thriller about a corrupt L.A. cop, will end up being a $75-million hit. Audiences have also flocked to see family fare ("Monsters, Inc."), sentimental sci-fi drama ("K-PAX") and romantic comedy ("Serendipity"). The true sign that the industry's heart-tugging, we're-all-in-this-togetherness was over: When MGM blamed the poor opening of "Bandits" on older moviegoers staying home to watch anthrax-scare news coverage, studio rivals hooted with derision.

After a much-publicized FBI warning, studio lots have heightened security, but it's hard to find anyone who still believes in the "Hollywood is forever changed" rhetoric that made the rounds in the emotion-charged days immediately after Sept. 11. As USA Television chief David Kissinger, in a rare display of executive candor, told the New York Times: "People need to be excused for anything we said.... We were blithering, terror-stricken and shocked, and we shouldn't be held accountable for much of what we said."

The truth is that when times are bad, people find solace in going to the movies. Hollywood broke box-office records during the Depression, and it hit new attendance highs during World War II. Think of it this way: Did the terrorist attacks prompt you to start wearing different clothes or stop eating at your favorite restaurant? Movies are a visceral experience, not an intellectual pastime, or more of us would have gone to see "Pollock" instead of "The Mummy Returns."

As a culture, our entertainment tastes are too deeply ingrained to be altered by one cataclysmic event. Like it or not, the visceral kick of action-hero exploits has become part of our collective pop subconscious. Is it any wonder that some New Yorkers, asked to describe the first moments of the World Trade Center attack, said it was like a Jerry Bruckheimer movie?

This doesn't mean that change won't occur at deeper levels than weekend box-office accounting. I've talked to screenwriters who are eager to tell stories with more substance. But they still have to persuade someone to make them. If you're an executive in Hollywood, part of your job is to keep your ear to the ground—it's good business to give customers what they want. The difference is that the movie industry's customers aren't only in Denver and Des Moines. They're in Berlin, Tokyo and Bogota. "The Mummy," which did $155 million in domestic box-office, took in $257 million overseas. Movies have become a global, one-size-fits-all business.

That's one reason not to expect a lot of movies to deal directly with home-front themes, since moviegoers in Madrid and Mexico City, to say nothing of Cairo or Jakarta, view the terrorist attacks and our military response in a very different light than people in Syracuse or Sacramento. Most of the current studio ideas fit pretty neatly into the action-adventure mold, focusing on projects where the heroes could be the metaphoric equivalent of the courageous New York firemen or the passengers of United Flight 93 who apparently overwhelmed the hijackers, preventing untold more destruction.

A week after the terrorist attacks, Disney's Eisner went over his development slate with his top executives. The discussion turned to "The Alamo," the stirring saga of a band of outnumbered Texans who fought to the death against a massive Mexican army. The project had been plodding along, but Eisner urged immediate action, wanting to know if the movie could be in theaters next summer. It won't happen that quickly, but Eisner's enthusiasm put the movie on a fast track: The studio has hired John Sayles to rewrite the script, with Ron Howard on board to direct.

Even though the film is set in 1836, the events seem very relevant today. "It's not about patriotism so much as about individuals who take a stand," says Brian Grazer, the film's producer. "It's about how Americans struggled to survive. You could say it reminds us of who we are."

Writers who've been in meetings with top Warner Bros. production executives say the studio is looking for a modern-day "Rambo" saga, believing the country is eager to see a hero triumph over great adversity. I had lunch with another studio production chief last week who said he'd like to see a new "Dirty Harry-type" hero, believing that moviegoers today have a thirst for a revenge fantasy where good triumphs over evil.

These projects wouldn't arrive until 2003. Hollywood is still busy making films that were put into motion long before Sept. 11. The movie business, sad to say, rarely reflects our culture's transforming events, in part because studios are largely focused on creating easily digestible franchise movies, in part because there's usually a two-year lag between a film's origin and its arrival in theaters.

So don't expect much urgent reflection from Hollywood. The studio lots may be full of SUVs flying American flags, but the movies that'll pay the bills next year are "Spiderman," "The Scorpion King" and "Star Wars Episode II: The Attack of the Clones." Even in our new Age of Anthrax, escapism is still king.

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

From the LA Times, 9/10/02:

THE BIG PICTURE

As Usual, Hollywood Is Slow to Focus

By PATRICK GOLDSTEIN

In the past couple of weeks I've been getting calls and e-mails from journalists working on Sept. 11 anniversary pieces, all asking the same question: Has our pop culture changed since last fall's terrorist attacks? (That answer is easy: no.) It's the follow-up question—why not?—that can't be answered quite so easily.

Finally, I came up with an answer that isn't as glib as it might first appear. I started telling people to watch the MTV Video Music Awards, which have been endlessly replayed over the past 10 days. If you want to understand what award presenter David Lee Roth described as "the front bumper of American pop culture," the MTV awards are the place to start.

Like so much of today's pop culture, the awards are relentlessly self-referential and disposably hip, from the fashion and the music to the videos themselves. I doubt that anyone can remember who won best rap video this year, much less last September. The show lives in the moment, which is why it's such a good cultural barometer.

If the MTV awards have a message, it's that our pop culture is anything but monolithic. More than ever before, thanks to our omnivorous media outlets, we have a bipolar pop culture; it is idealistic and cynical, hip and square, serious and trivial, new-fashioned and nostalgic, all at the same time. The MTV awards certainly ran the gamut from sublime to ridiculous and back again, from Bruce Springsteen's inspiring rendition of "The Rising" to Eminem's bratty petulance to a mournful appearance by the two surviving members of TLC to Sheryl Crow's somber "Safe and Sound" to Michael Jackson's wacky acceptance of a nonexistent "artist of the millennium" award to Shakira, who shook her booty in an outfit that looked like it had last been worn by Raquel Welch in "One Million Years B.C."

The show went on almost as long as the Academy Awards, but unlike the Oscars, which represent black-tie sobriety, the MTV awards are as giddy as a kid with a helium balloon, capturing what is most silly and unpredictable—and thus most real—about our culture. One of the dangers in writing about pop culture, especially in the wake of a seismic event like Sept. 11, is the temptation to make sweeping generalizations about the culture and where it's going. Vanity Fair's Graydon Carter is still being ribbed for loftily predicting the death of irony, and I'm hardly one to talk, having written a column last September foolishly forecasting that the terrorist attacks "may have brought to a close a decade of enormous frivolity and escapism."

We were all as wrong as weathermen are about the weather, probably because we were speaking from our hearts, not with our heads. Things haven't changed that much in Hollywood because of the nature of our pop culture and of the way the movie industry works. In hindsight we should have known that.

Sept. 11 will always be a signal event in this country's history, like Pearl Harbor or the Kennedy assassination, but in all honesty, it didn't change the entertainment industry any more than it changed the automobile business. People got on with their lives. Vanity Fair went back to air-kissing Tom Cruise and other celebrities. Cable news moved on to shark attacks and child abductions.

In Hollywood, everything was basically back to normal within a month of the attacks. In early October, moviegoers turned up in droves for "Training Day," even though it presented a disturbing vision of police corruption at a time when cops and firemen were being lionized as gung-ho heroes. That doesn't mean we don't want to see good cops too—how would network TV survive without 'em? It's simply another example of our bipolar culture: We find gangsters and thugs just as compelling as any saints or heroes.

The MTV awards are also a bracing reminder that in a messy democracy like America, our culture is full of contradictions. It doesn't travel in one straight line, it lunges left and right, forward and backward.

MTV isn't the only place where Michael Jackson and Rudy Giuliani are on the same stage. I flipped over to NBC the other day and found Sen. Fred Thompson (R-Tenn.) gravely discussing momentous world events on "Meet the Press," full well knowing he'll pop up on TV later in the year, this time as an actor, putting crooks away on "Law & Order."

Pop culture is America's ultimate melting pot. Turn on Top 40 radio and you can hear everything from steamy funk like Nelly's "Hot in Here" to cloying pap like Kelly Osbourne's "Papa Don't Preach." On TV, you can find hit shows with the cerebral elegance of "The West Wing" or the kitschy corn of "American Idol." The movie industry's current box-office chart has just as much reach, with the ultra-old-fashioned "My Big Fat Greek Wedding" attracting as many moviegoers as the ultra-hip "XXX."

What the movies don't do is make films about touchy topical subjects, which is why there are virtually no Sept. 11 projects in the works at major studios. A big part of this is simply demographic: Hollywood is in the youth culture business. Its mandate is to provide its teen fan base with comic-book heroes and escapist comedies.

Still, many people find it perplexing that Hollywood has taken such a hands-off attitude toward Sept. 11 when the news media has covered the story so extensively. The truth is that the news media's often obsessive coverage has in itself discouraged filmmakers from pursuing the topic.

"Frankly, what story could you possibly tell that hasn't been on Larry King?" asks Danny Goldberg, head of Artemis Records, which will soon release a Steve Earle CD that includes a controversial ballad about John Walker Lindh, the jailed American Taliban. "Pop culture rarely mirrors what's just been in the news. You go to the movies to get away from what's in the news."

But it's also fair to say that Hollywood has largely divorced itself from the nitty-gritty of today's pop culture. Like MTV, the studio films are intensely youth oriented, but unlike MTV, the movies strip away most of the culture's rough edges.

Most studios are scared by scripts that are too edgy or original, so they buy a lowbrow comedy or a predictable thriller—and then hire an ultra-smart screenwriter to do a rewrite that gives it a hip sheen.

It's no wonder Hollywood has become such a lumbering, top-down business—everything has to get retouched and enhanced before it can finally go before the cameras.

At some studios, even though a year has past, they're still debating how to deal with Sept. 11. In pop music, the topic is already old hat—everyone from Bruce Springsteen to Neil Young to Toby Keith has penned Sept. 11-related songs. Musicians can react almost as fast as CNN—they don't need a studio greenlight to get a topical song on the radio. Ditto for network TV: "The Practice" had an episode earlier this year about a woman whose husband was detained in Guantanamo Bay as a suspected terrorist.

The movie business moves at a glacial pace. Disney, for example, has been working on a new version of "The Alamo" for years. The script was languishing when, in the days following Sept. 11, Disney chief Michael Eisner seized on the idea that American audiences would embrace "The Alamo's" stirring last-stand heroics. The project was kicked into high gear, but nearly a year later, the movie is still unmade, slowed by a series of rewrites and battles over the film's budget.

Compare this to Disney-owned ABC, which has a TV movie in the works (also at Eisner's behest) about the nine Pennsylvania coal miners who were rescued this summer that could be on the air as early as February.

But just because people are in a flag-waving mood politically doesn't mean they're feeling patriotic culturally. The last time we were in a prolonged war, during the height of the late-1960s escalation of the Vietnam War, you could watch firefights on the TV news every night, but you saw few signs of the raging conflict at the local movie house. Hollywood's first crop of great Vietnam movies—"The Deer Hunter," "Apocalypse Now" and "Coming Home"—didn't hit the screen until a decade later.

The one constant about our pop culture is that it's restless and unpredictable, always embracing new ideas and fashions at a dizzying speed. At MTV, shows rarely stay on the air for more than a couple of years. Their programmers know the channel's audience is always hungry for the next New Thing.

In Hollywood, the studios have stopped trying to keep up; they'll settle for the next Old Thing. Their major response to Sept. 11 is a belief that we crave men of valor, a hunch bolstered by the box-office success of "Gladiator."

So studio development slates are chock-full of historical dramas about Alexander the Great, Hannibal, Constantine, King Arthur and, of course, the warriors who died at the Alamo. History is a safer place to find unqualified heroes, especially ones who haven't been overexposed on CNN.

Copyright 2002 Los Angeles Times

From the St. Paul Pioneer Press:

Posted on Tue, Nov. 16, 2004

Americans tune out world, turn on TV gore

LAURA BILLINGS

America loves dead people.

On any given night on network television, you can usually watch a fictional character suffocate in a plastic bag, get her brains blown out, get buried alive in an underground explosion, or have his vital organs cut into wafer-thin slices by one of several forensic scientist hotties, who can talk in grim and reverential detail about all the harm that can come to a human body.

No wonder when someone important dies in real life, it's not nearly as entertaining.

This is one of several lessons we can draw from the recent firing of a CBS news producer who overrode network policy by assuming that the 16 million or so Americans watching "CSI: NY" last Wednesday night might be interested in knowing that Yasser Arafat had died.

You can see why someone might make that mistake. After all, we had an election recently in which voters claimed that concern about terrorism was one of the central issues that had driven them to the polls. Arafat, who actually happened to be a terrorist, not to mention a Nobel Prize winner, certainly seemed like the kind of complex character Americans would want to know more about, and whose death might be worth considering for at least five minutes before the local news.

Unfortunately, Arafat's passing was not nearly as compelling as the restaurant employees killed in a multiple homicide on that night's episode, or the fun little subplot about the amputee found dead in his bed.

Irate viewers called to complain. CBS apologized. And the producer, referred to as "overly aggressive," is now looking for other opportunities.

Perhaps this producer was unaware that a Pew Research Center study in 2002 found that only 48 percent of Americans could correctly identify Yasser Arafat as the Palestinian leader, after the four decades his name had been in the news. Of course, it could be worse. Fewer than three in 10 Americans could correctly identify Donald Rumsfeld as secretary of defense, even though he's been in the public eye almost as long.

So much for that resolution we made after 9/11 to pay attention to what was happening in the world.

It really was just a few years ago that Americans claimed to be more interested in foreign policy and international news. For a while, we committed ourselves to worrying about women's lives under the Taliban, and decided on a preferred spelling of al-Qaida, and listened as Madeleine Albright and New York Times columnist Tom Friedman explained world affairs on "Oprah." In a 2002 survey of 218 editors of U.S. newspapers, 95 percent of them said that readers were more interested in foreign news and 78 percent were allocating more space to world news.

But did anyone pay attention? Probably not as many as should have. Four out of 10 Americans still think Saddam Hussein had something to do with 9/11.

It's true there was an uptick of interest in foreign reporting among college-educated news consumers, who were already inclined to follow international news. But a year after 9/11, the Pew Research Center found Americans had lost their alleged appetite for world news. In fact, 65 percent of people with moderate to low interest in international news said they didn't follow it because they felt they lacked the background to make sense of it. Some 51 percent said it wasn't worth watching because "nothing ever changes."

Another 45 percent said world events "don't affect me." And 42 percent said they didn't pay much attention to world news because there was too much coverage of war and violence.

Maybe that's the reason 66 ABC affiliates decided not to run "Saving Private Ryan" on Veteran's Day last week. Realistic portrayals of the horror of war, bombs and F-bombs — even if they do happen on French soil — may be too much for our delicate sensibilities and moral values. When we want to see war and violence, we'd prefer to see it celebrated in the form of a video game such as "Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas," which has already sold 32 million units.

As for those poor viewers who were subjected to world news and deprived of the last five minutes of "CSI: NY," CBS gave them a rain check. TV viewers' commitment to finding out how things came out on a cop show turned the episode rebroadcast on Friday into the night's ratings winner.

More on getting serious in the popular media

Drawing Fire: Cartoon Museum Explores What Happens When the Funny Pages Take on Serious Issues (1/28/03)

Related links

Memo to Hollywood: get real

Terrorists followed media violence script

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.