Native traditions of scalping

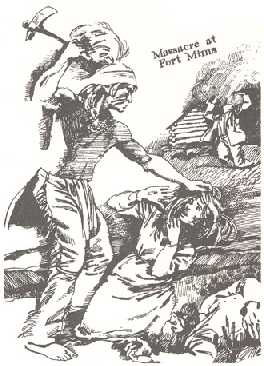

Native traditions of scalpingFrom Killing Custer by James Welch, pgs. 140-143:

Native traditions of scalping

Native traditions of scalping

From Killing Custer by James Welch, pgs. 140-143:

Tribal warfare was traditional and continual. Usually the battles were centered on revenge, a kind of nonstop revenge, war parties going back and forth between tribes. The Sioux hated the Crows and Shoshones, or Snakes. The Crows hated the Sioux and Blackfeet. The Blackfeet hated the Crows and Snakes and Assiniboins. Always, they sought to kill each other, to count coup, to humiliate, to steal women and horses, to avenge the death of warriors who had been killed in a previous battle. Sometimes alliances were formed to present a more powerful force. The Sioux and Cheyennes and Arapahos were such an alliance. The Arikaras, Hidatsas, and Mandans formed an alliance. The Crows and Snakes presented a united front, when possible.

Most tribal battles involved a lot of skirmishing, a lot of coup counting, with very few casualties. Indians were not out to annihilate each other, but to exact revenge or cover themselves with war honors. In most instances, it was better to humiliate the enemy than to kill him. A Blackfeet account tells of a party of horse raiders who stole into an enemy camp one night and made off with some buffalo runners. One of the raiders found a sentry sleeping at the base of a ledge near the edge of camp. The warrior pissed on the sentry from the ledge, then stole off into the darkness. This feat was talked about in the Blackfeet camps for years to come. The Blackfeet got off with the horses, and the drenched sentry had to explain to his chiefs what happened. It was almost better than counting coup. It gave the whole tribe a chuckle.

Of course, warfare was more serious than that. It was important to lift the enemy's hair, both as a warning to the enemy and as a morale-booster to the scalper, his party, and other tribesmen. Nothing delighted a waiting camp more than to see scalps on the lances of returning warriors. These scalps were passed around, talked about, laughed at, sometimes thrown into the fire or given to the dogs in disdain. Often the hair decorated a lodge or was sewn onto a war shirt. White men's hair was taken but was less desirable because it was usually short. Some of the white men were balding and weren't worth scalping. But scalping was an institution among the Plains tribes. A scalp was a trophy of war, just as it became for the whites.

Torture, and the mutilation of bodies dead and alive, was, and is, more problematic, if only because it is odious to civilized society. Throughout the years, those cultures which have "seen the light" have been horrified by the desecration of bodies committed by barbarians of other cultures. We think of the Nazis in World War II who justified torture and mutilation of live bodies for "scientific" purposes. The communists in Russia, especially under Stalin, committed similar atrocities on ethnic groups. The Khmer Rouge beheaded and chopped the limbs from innocent people and left them by the thousands in the killing fields of Cambodia. The military did the same in El Salvador. Thousands of Moskito Indians died in such a horrible fashion. African leaders, in their beribboned military costumes and with their weapons supplied by the United States, Russia, France, and Israel, continue to kill and mutilate their tribal enemies.

European tribes beheaded their foes. posting the heads along roads or at the town gates as a grisly warning to those who would oppose them. The Catholic Church in Europe, especially Spain, during the Inquisition tortured and mutilated those who it thought were possessed by the devil—or those it simply wanted to get rid of for political reasons. The Puritans in America burned, crushed, and drowned people almost gratuitously in their effort to root out witchery. Thousands, probably millions, of people have been treated in a similar fashion by the religious right of all cultures.

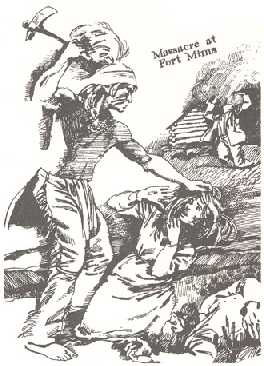

Soldiers who go to war commit unspeakable acts to their enemies. Homer tells us that in the Trojan War, Achilles dragged Hector's mutilated body behind his chariot for twelve days. From the time of the Slaughter of the Innocents to My Lai in Vietnam, war has created a callousness toward human life to such a degree that torture and mutilation have become accepted practices. Witness the Serbs in their treatment of the Muslims, torturing and mutilating men, raping women to death—all in the name of ethnic and religious purity. Virtually all warfare has been conducted for such contrived principles as ethnic and religious purity.

Euro-American traditions of scalping

—By Philip Martin

Stereotypes are absorbed from popular literature, folklore, and misinformation. For instance, many children (and adults) incorrectly believe that fierce native warriors were universally fond of scalping early white settlers and soldiers. In fact, when it came to the bizarre practice of scalping, Europeans were the ones who encouraged and carried out much of the scalping that went on in the history of white/native relations in America.

Scalping had been known in Europe, according to accounts, as far back as ancient Greece ("the cradle of Western Civilization"). More often, though, the European manner of execution involved beheading. Enemies captured in battle — or people accused of political crimes — might have their heads chopped off by victorious warriors or civil authorities. Judicial systems hired executioners, and "Off with their heads!" became an infamous method of capital punishment.

In some places and times in European history, leaders in power offered to pay "bounties" (cash payments) to put down popular uprisings. In Ireland, for instance, the occupying English once paid bounties for the heads of their enemies brought to them. It was a way for those in power to get other people to do their dirty, bloody work for them.

Europeans brought this cruel custom of paying for killings to the American frontier. Here they were willing to pay for just the scalp, instead of the whole head. The first documented instance in the American colonies of paying bounties for native scalps is credited to Governor Kieft of New Netherlands.

By 1703, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was offering $60 for each native scalp. And in 1756, Pennsylvania Governor Morris, in his Declaration of War against the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) people, offered "130 Pieces of Eight [a type of coin], for the Scalp of Every Male Indian Enemy, above the Age of Twelve Years," and "50 Pieces of Eight for the Scalp of Every Indian Woman, produced as evidence of their being killed."

Massachusetts by that time was offering a bounty of 40 pounds (again, a unit of currency) for a male Indian scalp, and 20 pounds for scalps of females or of children under 12 years old.

The terrible thing was that it was very difficult to tell a man's scalp from a woman's, or an adult's from a child's — or that of an enemy soldier from a peaceful noncombatant. The offering of bounties led to widespread violence against any person of Indian blood, male or female, young or old.

Paying money for scalps of women and even children reflected the true intent of the campaign — to reduce native populations to extinction or to smaller numbers so the natives could not oppose European seizure of Indian lands.

Scholars disagree on whether or not scalping was known in America before the arrival of Europeans. For instance, in 1535, an early explorer, Jacques Cartier, reportedly met a party of Iroquois who showed him five scalps stretched on hoops, taken from their enemies, the Micmac. But if scalping in pre-European America occurred, it was fairly rare, certainly not an organized government practice done for money.

Regarding the philosophy of many native tribes, note the following quote, from a man, Henry Spelman, who lived among the Powhatan people and described their approach to warfare: "they might fight seven years and not kill seven men." (in Kirkpatrick Sale, The Conquest of America, p. 319), Many native societies did not engage in wars of any kind. Native scholar Darcy McNickle estimates that 70% of native tribes were pacifist (in Allen, Sacred Hoop, p. 266).

By anyone's standards, the Europeans were more skilled and deadly in the practice of war. Paying bounties for scalps was just one of many ways in which the Europeans took warfare to new levels of violence.

The Indians were pulled into warfare against white settlers by rival European factions in America. In wars between the French and British, and between the British and the American colonists, each side encouraged their Indian allies to mount violent attacks on the other's population.

Popular literature and newspapers loved to describe any Indian attack in great detail in a blood- thirsty, sensational manner. Readers easily believed that Indians were all "savages," — as that is what the newspapers said. And this helped the government justify its practice of driving native families off tribal lands or killing them.

Almost every fictional account of scalping blames the Indians. The European involvement is over-looked. But it is wrong to do so. Oral history collected from native peoples differs greatly in the interpretation of who was the most cruel, why conflicts were started, or who was defending their family homes from whom.

But it is the victors who write the official history books, and it is the white viewpoint which has dominated our image of the American past.

—From information in Unlearning "Indian" Stereotypes (Council on Interracial Books for Children) and other sources. Philip Martin is a folklorist and book editor for Rethinking Schools.

Did Europeans originate scalping?

An exchange with correspondent Al Carroll on the subject, begun 4/22/03:

On your link to [Louis L'Amour's Last of the Breed], you repeat the claim Europeans introduced scalping.

They did greatly accelerate scalp taking by offering bounties. But it's a longtime practice among many Native peoples.

In fact, Native soldiers and Marines still took scalps during both world wars. (It may have gone on during Korea, Vietnam, and Gulf Wars I and II, but I haven't found any cases of it. At least, not yet.) Scalp dances were held after both wars too. I've found accounts about the Paiute, Lakota, Kiowa, etc. The meaning of scalping is just very different. For Europeans it was just trophies. For US soldiers in Vietnam, it was a way to get a body count. But for many Native groups, scalp taking has different meaning. Here's some articles I've collected.

Al

News From Indian Country 8/31/2000 V.XIV; N.16 p. 1A

Chief Big Foot's hair-lock returned to descendants: Leads to rebirth of sacred ceremony

Author

Kent, Jim

Article

Apart of the Lakota culture has been re-born, as the remains of a victim of the Wounded Knee Massacre finally came home.

A hair-lock taken from the body of Chief Big Foot was returned from the Barre Library and Museum, in Barre, Massachusetts, where it had been on display for more than a century.

Big Foot, along with more than 300 of his Minneconjou band, were killed by members of the 7th U.S. Cavalry on December 29, 1890. Many members of the band were unarmed women and children. The bodies of the dead were left where they lay for days until a blizzard that enveloped the region had passed.

The hair-lock is believed to have been taken from Big Foot's remains—by the scalp—by either a 7th Cavalry trooper or a resident of the New England region who happened to be passing through South Dakota at that time.

"It's good to have my great-great-grandfather back after all these years," said Leonard Little Finger, the nearest direst descendant of the chief.

Little Finger became aware that the hair-lock was in the Barre Museum about five years ago. Two years of negotiating for its return included a requirement that Little Finger prove his descendency.

He said that he can trace his ancestry beyond Big Foot's father, One Horn, whose portrait was painted by renowned Western artist George Catlin.

Little Finger was accompanied on his journey to repatriate the hair-lock by six members of Big Foot's four descendant families. Included in the group were four young girls — one from each of the families who were acknowledged to be virgins. Virginity was a requirement for their taking part in the repatriation, as they would be directly involved in caring for Big Foot's remains.

"I think it was a great honor to be chose to be a part of this ceremony", said Lucinda He Crow, one of the four. "We're in a position of responsibility and respect, because of our purity. Because of that, we're seen as being able to carry our own prayers and the prayers of our people to the Creator."

The hair-lock was handed over to Little Finger by the president of the Museum's Board of Trustees on July 29. Little Finger said that although he detected uneasiness in the Board members' demeanor upon their initial introductions, by the time the Lakota contingent left the museum, those feelings had Dissipated.

"We tried to leave with a good feeling between everyone involved," said Little Finger. "The members of the Board did cooperate with us in the repatriation and we'd like to keep a line of communication open with them."

He said that other items from the Wounded Knee Massacre, including sacred pipes, remain at the Museum.

Little Finger and his party returned to Pine Ridge on July 30, bringing the hair-lock to family and located just south of the village of Oglala. Once there, it was placed in a traditional lodge for the start of a Keeping of the Soul ceremony. The ceremony, outlawed by the federal government in 1890 along with the Ghost Dance movement, has not been openly performed on the reservation for over a hundred years.

Traditionally, the ceremony would involve keeping a lock of hair from the deceased for a period of one year, as a sign of mourning. Since Big Foot's hair-lock had already been held at the museum for 110 years, Little Finger said it was determined that the ceremony would last for four days, the current Lakota period of mourning.

During that time, family and community members were permitted to view that hair-lock and offer prayers within the lodge. Little Finger also offered an open invitation to members of the public, including non-Natives, to take part in the ceremony.

"I think that this is a time of healing for all people, not just the Lakota," he said. "I'd like to be able to use this as a means of helping build a bridge of cultural understanding with other people."

At midnight on August 3, the second part of the ceremony took place, called the Releasing of the Soul. Words of acknowledgement to Big Foot were given a representative of each of the four families, followed by the prayers of spiritual leader Richard Broken Nose. Then, with 60 family and community members watching, the hair-lock was ceremoniously placed into a sacred fire in the middle of the lodge. The soul of Big Foot had finally been released.

Little Finger said he saw the return of the hair-lock as an opportunity to help his people to heal, by bringing back aspects of their culture—including the Keeping of the Soul ceremony—that most had never seen in their lifetime.

Char-Koosta News 7/30/1999 V.30; N.44 p. 1 Word

Scalp dance results in marriage

Article

Patricia McClure and Sam Matt Buffalo were married according to Salish tradition on July 21 at the collaboration grounds here. They'll be repeating the deed, 20th century style, tomorrow (July 31) at 2 p.m.

The two re-enacted the Salish scalp dance with assistance from the bride's uncle, Johnny Arlee, as part of Salish Kootenai College's "Summertime Language Gathering II," held July 19 through 22.

In the past, the scalp dance followed a victory in battle. Women would dress up in men's outfits and dance to special songs, carrying "coups sticks" — staffs decorated with scalps that were used to display contempt for the enemy. A marriage resulted when a woman placed her staff on a man's shoulder. If he didn't knock it away, they were considered husband and wife from that point on.

"That was one of the ways to get married a long time ago," Arlee explained in his book, Over a Century of Moving to the Drum.

The practice was later outlawed.

Arlee was part of a group of tribal members several years ago who suggested performing the ceremonial dance on film, as a way of keeping the memory of it, if not its actual significance, alive.

Article copyright Char-Koosta News

Native Americas 12/31/2001 V.XVIII; N.3&4 p. 88

Gallery Exhibition: New Native Warrior Images in Art

Author

Harjo, Suzan Shown

Article

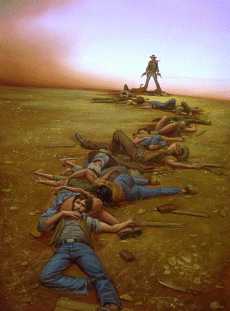

Warrior images have dominated "Indian art" for more than a century. Stereotypes of Plains warriors of the late 1800s have constituted most of the visual information the world has about Native peoples. Non-Indians churn out most of the warrior kitsch, but Indians manufacture a fair share of it as well. Plastic warriors, wooden warriors, warriors painted on velvet and stamped on rubber tomahawks — warriors in every color and garish combination of the rainbow.

"I've seen enough warriors praying to the moon or jumping out of cow skulls to last a lifetime," says painter Judith Lowry (Mountain Maidu and Hamowi Pit River) of Nevada City, Calif. The proliferation of "warrior art" prompted her to paint Roadkill Warrior: The Last of His Tribe. She says it is a "sad little painting about the attempt to keep traditions alive."

Lowry says she does not want to "deprecate what these guys do" and has deep affection and admiration for those who dance and celebrate Native culture, whether in the pow-wow arena, or in traditional ceremonies. Her father was a World War II hero in the Pacific. She often paints him in uniform or Indian honoring apparel, but never in hackneyed "warrior" poses. Sometimes she paints a "female warrior/cheerleader," in the same costume — complete with majorette boots and war bonnet — worn by the cheerleaders at Sherman Indian Institute, her father's high school.

Expanding Warrior Images and Traditions

Painter Mateo Romero (Cochiti) is among today's artists whose warrior images include veterans of American wars. He, like Lowry, pays tribute to his father, Santiago Romero, a painter who had part of his hand shot off when he was a Marine in Korea.

"There's a contemporary connection with some historic ideas about being a warrior and part of a warrior society," Romero says. "There's a tremendous sense of patriotism [and] an incredible irony about that too. You would think that serving in the military of the colonizing country and worshipping in the colonizing religion would be anathema to Indian people, but it's not. There's a weird kind of compartmentalization."

At the elder Romero's Cochiti Pueblo funeral in New Mexico four years ago, "military honor guard shot rifles and the people loved it," recalls Romero. "It has the same kind of mystique as being part of the Scalp Society or another warrior society."

Romero said his father was asked to "dance the scalps," which must be done by a veteran who has seen hand-to-hand combat, but he would not do it. He was angry about the whole thing. He felt duped, betrayed by the Marine Corps — he was left out there to die on a Korean mountain top."

"I did a Scalp Chief piece about that.," Romero says. "It's a line of Corn Dancers who come through a cubist space, a fractured space, like the sense of being a traditional person and going into this other-world experience, [under] harsh terms, and paying the price" (page 90). He says the painting also has "the pathos of my uncles who all served in Vietnam, who all saw action, who all came back in varying degrees of disrepair, who all became alcoholics and who all died — except the ones who quit drinking."

Buffalo Spirit 6/30/2000 p. 10

Designs recount personal achievements

Author

Burke, Marie

Article

The designs painted on Blackfoot war tips are symbolic records of their owners' truth for all to see.

James Dempsey, Native Studies associate professor at the University of Alberta, is writing his thesis on Blackfoot warrior art forms, including the designs found on buffalo robes and tipis.

"They were the gamblers tipis, quite literally," said Dempsey who adds there may be as many as 10 warriors' achievements painted on one tipi.

The designs recounted what happened in the warriors' lives, their accomplishments in battle or coups. It was about their standing in the community and their recognition by the community, Dempsey said.

The symbols also tell about the risks taken by the warriors in the event or the acts they committed and that's why they are called the gambles tipis.

"For example," said Dempsey, "the taking of a scalp, a white haired scalp, that meant it was from an old person. That was a very high gamble to take."

During a battle the old people were kept in the middle of the camp. For a warrior to risk going into the middle of any enemy camp and to come out alive spoke of the greatness of his risk in battle, said Dempsey.

Rob's reply (4/22/03)

Scalp ceremonies and the like don't exactly prove that scalping wasn't European in origin, right? The ceremonies could've developed in the last few hundred years. Seems to me the legend that scalping came from Europeans is pretty well-rooted in Native lore. And it's documented or at least claimed in several sources.

I'm glad to raise doubts about any belief, even a pro-Native one. But I don't think we can or should dismiss a commonly held belief too easily.

Al's reply (4/23/03)

None of the scalp ceremonies or dances have stories around them that mention European origin, as far as I know. They all mention the dances' origins as being in combat with other Natives.

One of those articles I passed on is about the Salish scalp dance. The Salish are in Washington State. It's not too likely they would've gotten scalping from the Dutch in New Amsterdam (later New York) like some people claim the Iroquois did.

The Kiowa are also big on scalp dances for their vets (using German and Japanese scalps), so I've read quite a bit on this. It's not too likely they would have had contact with the Dutch several centuries ago either. Wm Meadows, Louise Lassiter, and Charlotte Heth all wrote about their scalp dances, and I haven't found any mention of whites in their accounts of the dances' origins.

I don' think I've ever heard any Native lore about a European origin for scalping. I'd always thought that claim came from the Sixties counterculture and was about as credible as the supposed Chief Seattle speech.

>> I'm glad to raise doubts about any belief, even a pro-Native one. But I don't think we can or should dismiss a commonly held belief too easily. <<

I've never heard anyone Native having that belief. I don't really think of the origin of scalping as having either a pro or anti-Native POV, since both Europeans and Natives did it in wartime (and still do). The meanings attached to it and the reasons for doing it are more important, trophy collecting or body counts for Europeans vs reconciling the spirits of the dead, celebrating warrior prowess, etc, for Natives.

If you run into anything that gives a European origin for these practices, let me know.

Al

Rob's reply (4/24/03)

You often see a European origin of scalping claimed along with the origin of the word "redskin"—which some say came from the European practice of collecting bloody Indian scalps.

I searched my site for mentions of the origin or history of scalping. Mentions from people other than me, that is. <g> The genocide page includes mention of a 1722 Scalp Act in Massachusetts, and the savage NA page includes a quote from Vine Deloria Jr. on the European origin of scalping. So there's some evidence for the idea that Anglos championed the practice.

We know guns, liquor, horses, and smallpox spread rapidly from one tribe to another. It's not inconceivable to me that the practice of scalping could've spread as quickly. It might've resonated with the traditional Native thinking as a more permanent way of counting coup.

Whole tribes have moved and then developed ceremonies and ties to their new locations since Columbus. If you believe archaeologists, the Navajo didn't arrive in the Southwest until the 16th or 17th century, yet they have a complete cosmology linking them inextricably to their four sacred peaks. The point is that cultural change and diffusion can happen rapidly. It doesn't prove that scalping came from Europeans, but it supports the idea that it's possible.

I'll be glad to post your sources on scalping and see what people think of them. It could be another interesting discussion.

Rob

Al's reply (4/24/03)

Sure, it'd be interesting. I'd especially like to hear people of different NDN nations talking about what they know.

Found these using a google search that say NDN origins among a wide variety of tribes:

This was the only article I could find which mentioned any claim of a European origin, by an Allegheny chief in the 1820s who blamed the Dutch. But Axtell concludes the opposite.

An Analysis of Scalping Cases and Treatment of the Victims' Corpses in Prehistoric North America

Points out no one claimed a European origin for scalping until post WW2.

Eastern Band Cherokee newspaper, on Cherokee scalping.

Most of it's a pretty unreadable pathology report, but 3/4 of the way down they conclude the bodies they found in the upper Missouri from pre Columbian times were often scalped.

Cartier's & other French explorers' accounts of seeing scalps. I doubt the claim they were "trophies" though.

Scalping as spread by the Spanish, no position taken on the origin.

And then there's Wm Meadows book Comanche Apache and Military Societies, which goes into the scalp dances quite a bit. None of the Kiowa he talks with ever mention a European origin.

Al

This is from the H-Amindian academic listserv:

The subject, like that of human sacrifice, is difficult. An overiding acculturation of Western values often creeps in and makes it seem as though every action must be justified or denied. Many claim that scalping was introduced to native folks by Europeans but that is not likely. The taking of human trophy is one of the oldest and most common actions in the world. Strings of human teeth have been uncovered along the shore recently in Southern California. There is no doubt that scalping took place in Europe and was used by them against American native folks, both taking native scalps and paying natives for scalps.

Benjamin Franklin is thought to have authored a false letter circulated in the colonies and in Europe that purported to catalog scalps of women, children, farmers, and old folks, taken by Joseph Brandt and his followers. The letter was known to be false by the early 1800's but is an example of the Founding Father's use of propragandistic imagery of Indians' scalping to bring sympathy to themselves as victims of Crown and tomahawk. This can be found reproduced in the 19thc. biography of Brandt — Thayendenonga, and in one of the Rembrancer's following the revolution.

The Mohawk hairdo and other exotic haircuts in the Northeast are visual teases referencing scalping. The taunting young man is literally saying, "I have cut off all but that which you want. I have made it easy for you. Take it if you can." Scalping became more popular, was spread, became more prestigious, etc. because of the stimulation of Europeans without a doubt. The intentional use of scalping imagery, as with Franklin, to dengigrate natives is clear. The Declaration of Independence arguably takes its description of natives as merciless savages from the direction Franklin's forgery illustrates as a common theme employed by the Framers. Much like "reverse discrimination" is used today to try and gain sympathy by declaring the powerful are being harmed by the powerless, it rings hollow in the list of complaints against King George.

Robert DeNiro's use of a Mohawk haircut in Taxi Driver was meant to imply savagery and all loss of social control. Horatio Greenough's Rescue Group sculpture which used to sit on the Capitol steps depicted a juvenile-sized native with Mohawk haircut and scalping hatchet being restrained by a large benevolent European.

It is not the history of scalping that native folks need to concern themselves with, it is the use of the image of natives as savage that needs addressing. Human trophy was taken in Kuwait, Bosnia, and will be taken anytime men come into conflict. WW II saw this in abundance. As always, it is not the actions as they are human, it is the intrepretation that is political and social for which we must account.

Paul Apodaca

Chapman University

Thomas E. Mails' text __The Mystic Warriors of the Plains__ (Marlowe & Company, New York: 1975), pages 314-323 provide a unique glimpse into the art of scalping, its role in adornment, religion, and the "war count" system.

Ian K. Steele discusses some of the first documented scalp bounties found in his book __Warpaths: Invasions of North America__ (Oxford University Press, 1994). Most of his sources are connected to the use of scalp bounties by New Englanders in the 1670's. I'm sure there are many other sources that will come to light.

Mark J. Timbrook

Vermont College-Norwich

- -- - -- -

[2]

The short answer to the question about scalping is no, the French did not introduce scalping to North America. For the best discussion of this issue, see James Axtell and William Sturtevant, "The Unkindest Cut, or Who Invented Scalping," William and Mary Quarterly 37 (July 1980), 451-472.

Brett Rushforth

University of California, Davis

- -- - -- -

[3]

James Axtell wrote an excellent article that deals exactly with this question, which is published in his book __The European and the Indian: Essays in the Ethnohistory of Colonial North America__ (Oxford, 1981).

Best Wishes,

Michelle LeMaster

The Johns Hopkins University

- -- - -- -

[4]

Trophies as token of victory in combat are probably a cultural universal, in the sense that the practice is very widespread. They not only offer evidence that the enemy has been killed, but may also serve as a memento of valor. Generally, the part of the body that most typically represents the identity of the enemy is most likely to be selected. Some cultures prefer a nose or ear, others a scalp or an entire head.

The Isrealites, who practiced male circumcision (Genesis 17:10; 34:15), focused on the foreskin as a symbolic token of the wicked Other, in particular their uncircumcised Philistine enemies. Accordingly, when the youngest daughter of the Isrealite king Saul wanted to marry David, Saul informed the young warrior that he would accept 100 dead Philistines as dowry: "Vengeance on my enemies is all I want." And as recounted in the Old Testament: "David was delighted to accept the offer. So, before the time limit expired, he and his men went out and killed two hundred Philistines and presented their foreskins to King Saul. So Saul gave [his daughter] Michal to him" (1Sa 18:25).

Last semester, one of my older female students who had been a US Army nurse in Vietnam told me that American soldiers cut the ears of their Viet Cong enemies. Some, she said, dried them and sent them home to their girl friends. She knew a few who even wore necklaces with several dried human ears.

Historically, European warriors did take ears, noses, tongues, or heads for triumphant display. Traditionally, however, they did not take scalps. There are probably some exceptions. I myself discovered quite recently that Saxon farmer-warriors from my home area in the northern Netherlands, having defeated an invading army from the south, scalped one of its leaders, a high-ranking bishop. This occurred in late 13th-century Drenthe during the Battle of Ane.

In contrast, scalping was widely practiced in North America, also before European contact. Several early European observers such as Marc Lescarbot specifically mention this (see also Axtell 1981:214). However, customary scalping changed in the course of the late 17th century. Quoting from my 1996 book __The Mi'kmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival __:

"During the colonial wars in North America, Europeans began offering bounty for scalps, transforming the traditional trophy from a memento of valor into a commodity to be exchanged for cash or merchandise. Commercial scalping became common practice in the summer of 1689 when the Massachusetts government began recruiting Mohawk Indians from New York to take Wabanaki scalps. In reaction, the French Crown offered payment for English scalps. Drawing a racial distinction between themselves and the 'savages,' the English protested that 'setting a price upon Englishmen's heads [was] Unchristian and not agreeable to the custom of Nations.' Nonetheless, from 1693 onward, Wabanaki warriors regularly 'brough in English Prisoners & Scalps,' for which the French colonial government paid them good cash. Soon, the gruesome practice became commonplace, and anyone — Indian, French, or English — was eligible to scalp or be scalped. In other words, although Europeans did not introduce scalping to North America, they did institute its commercialization, turning tribal warriors into colonial mercenaries" (p.122).

Harald Prins

Kansas State University

Echoing the sentiments expressed by Paul Apodaca, I'd like to approach scalping from an art-historical perspective. One need look only so far as the sculpture and engraving of the so-called "Mississippian" culture. There is a famous shell gorget engraving from Tennessee held in the Heye Collection of the Museum of the American Indian depicting a man clutching a human head by the hair; also from the Heye collection, a massive stone pipe depicting an armor-clad warrior—complete with elaborate head-gear and ear spools—in the very act of scalping, or so it appears, using a talon-shaped cutting device that very much looks like one of the many flints of the famous Duck River, Tennessee, cache. By the way, the flint sculpture from this cache (last I heard at the University of Tennessee) is absolutely astonishing. I know I'm getting off topic, but I think if you ever have the chance, you should see these stone sculptures.

Anyhow, it is readily apparent that human trophy-taking existed in pre-Columbian North America. How widespread the practice might have been remains to be discovered. But, as Paul Apodaca mentioned, that is perhps not the most important aspect of this phenomenon.

CS Everett

Vanderbilt University

Rob's reply (7/23/06)

I finally digested and posted all the information Al provided on scalping. I'll concede that scalping probably wasn't European in origin. But a few more thoughts:

If we exclude this singular event, we're left with maybe a couple dozen cases in each of three regions. The Smithsonian alone has something like 14,000 Indian skeletons. Using these numbers, it seems less than 1% (<140 of 14,000) of the prehistoric Indians we've found were scalped. Based on this rough calculation, I'd say scalping was rare, not common.

Al points to scalp dances done by the Salish and Kootenai and Cochiti people. The Salish and Kootenai are located in Montana, not Washington (sorry, Al—you're thinking of the Coast Salish), on or near the northern Plains. Cochiti is located in New Mexico near the southern Plains. Historically the neighboring Apache and Comanche influenced Cochiti and the other northern pueblos.

I suspect these tribes borrowed their scalp dances from their neighbors relatively late in their history. That would have to be the case with the Apache, who didn't arrive in the Southwest until well after 1492. In fact, it's possible the tribes borrowed the dance, to honor their warriors, without borrowing the practice also.

In short, there's little evidence for widespread scalping across Native America. Most of it seems to have happened on the Plains and Plains-adjacent areas. As with every other stereotype, what the Plains Indians did doesn't represent more than a fraction of all Indian customs and practices.

Scalping, torture, and mutilation in the Stereotype of the Month contest

April Fools' joke on Indians

Indian societies practiced misogyny, torture, and cannibalism

AL baseball headline: "Indians scalp Red Sox to even series"

Satire: Chief "Running Tab" wants scalps to pay for illegals

Nunes: Illini were "a superstitious lot" of "handsome creatures"

Indians practicing cannibalism and torture dominated America

CSI: Miami: Victims are scalped, stabbed in eye by Indians

Colonial woman lionized for scalping Abenakis while fleeing

Anti-abortionist Stanek: "Sioux tribe plans to scalp its own"

Student editor calls Indians "savages," says he was "scalped"

Ark. liquor store mural shows Indian with scalp, war club

Mascot slogan ideas: "Scalp the Indians," "Char the Chiefs"

Hip Shot cartoons depict Indians who scalp, do rain dance

Online forum joke: "Why didn't Indians scalp brunettes?"

Limbaugh: Giago "scalped" after "pow-wow" in "tee-pee"

Harlem Valley Times head: "Indians scalp Lady Warriors"

Head: "Cowboys scalp 'Skins to maintain NFC East lead"

Mesa State College headline: "Mavs scalp Sioux 31-24"

Student article alleges Indians used drugs, scalped people

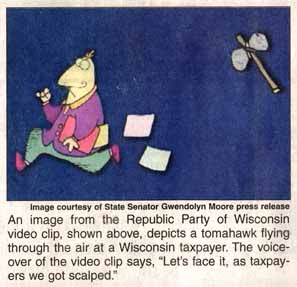

Wisc. GOP party's cartoon: Taxpayers were "scalped"

Quebec official's rationale: "We didn't scalp anybody"

Students paint "Scalp 'em," tomahawk on school grounds

Comic book shows Indians scalping and raping whites

More on scalping

Cahuilla Indians and scalping

Necklaces of Human Ears Through History: The scalping party, 'Blood Meridian' to Iraq

Native violence isn't traditional

Westerners provoked Indians, animals

Related links

Savage Indians

Indians as cannibals

Uncivilized Indians

Indians as warriors

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.