A conservative is a man who just sits and thinks, mostly sits.

Woodrow Wilson

A conservative is a man who just sits and thinks, mostly sits.

Woodrow Wilson

Scalia speaks his mind

Some pearls of wisdom from a leading conservative "thinker":

I belong to a school, a small but hardy school, called "textualists" or "originalists." That used to be "constitutional orthodoxy" in the United States. The theory of originalism treats a constitution like a statute, and gives it the meaning that its words were understood to bear at the time they were promulgated. You will sometimes hear it described as the theory of original intent. You will never hear me refer to original intent, because as I say I am first of all a textualist, and secondly an originalist. If you are a textualist, you don't care about the intent, and I don't care if the framers of the Constitution had some secret meaning in mind when they adopted its words. I take the words as they were promulgated to the people of the United States, and what is the fairly understood meaning of those words.

Justice Scalia, remarks at The Catholic University of America Washington, D.C. Oct. 18, 1996, on why the intent doesn't matter and the text does

That they thought the way I think is demonstrated by the 19th amendment, adopted in 1920. That is the amendment which guaranteed women the right to vote. As you know, there was a national campaign of "suffragettes" to get this constitutional amendment adopted, a very big deal to get a constitutional amendment adopted. Why? Why did they go through all that trouble? If people then thought the way people think now, there would have been no need. There was an equal protection clause, right there in the Constitution in 1920. As an abstract matter, what in the world could be a greater denial of equal protection in a democracy than denial of the franchise. [sic] And so why didn't these people just come to the court and say, "This is a denial of equal protection"? Because they didn't think that way. Equal protection could mean that everybody has to have the vote. It could mean that. It could mean a lot of things in the abstract. It could meant that women must be sent into combat, for example. It could meant that have to have unisex toilets in public buildings. But does it mean those things? Of course it doesn't mean those things. It could have meant all those things. But it just never did. That was not its understood meaning. And since that was not its meaning in 1871, it's not its meaning today. The meaning doesn't change.

Justice Scalia, remarks at The Catholic University of America Washington, D.C. Oct. 18, 1996, two paragraphs later, on why the text doesn't matter and the intent does

Rob's comment

No wonder this doofus's rulings are so hypocritical. He can't keep his views straight for more than two paragraphs in a row. Let's take a look:

First, Scalia is a textualist but doesn't go by the text itself. Equal protection means semi-equal protection or unequal protection. The men who ratified the 14th Amendment meant to limit this "equal" protection, but didn't intend to limit it.

Well, that's as clear as mud.

No, apparently Scalia goes by the "understood meaning," not the text. So if the Founders understood "speech" to mean talking or writing but not broadcasting or the Internet, Scalia must believe the 1st Amendment doesn't apply to electronic media. If the Founders understood "arms" to mean "muskets," Scalia must believe the 2nd Amendment doesn't apply to any weapon made after 1791. Right?

Don't count on it. In cases like this the double-talker will revert to the text, or perhaps proceed to the original intent. Who knows with such an intellectual goofball?

What does Scalia think Congress intended in passing a law if not the "understood meaning"? A hidden meaning? Maybe once or twice, but I suspect they mostly meant what they wrote. Going by the "understood meaning" means going by the intended meaning, which means going by the intent. Which Scalia said he doesn't do.

Which means this doofus is talking out of every side of his mouth—and a few other orificies as well. He's shopping for rationalizations just like one shops for shoes. He'll take one from Shelf A, one from Shelf B, one from Shelf C, and keep whichever one fits best.

In other words, he'll make up his mind according to his conservative dogma and find a justification for it later. Nice trick if you can get away with it.

Perhaps the scariest thing is that Scalia admits his woeful ignorance of Americans' thinking:

I'm not very good at determinating what the aspirations of the American people are. I am so out of touch with the American people. I don't even try to be in touch. People mention movie stars and I don't know who they're talking about. I get a blank look on my face.

So this slack-jawed moron doesn't have a clue what the people around him think today, but he can divine what Americans thought 100 or 200 years ago? How, by consulting the spirits? If you're incapable of reading minds, bright boy, stop trying to guess what the "understood meaning" or "intent" was before you were born. Start interpreting the law intelligently like your non-ideological counterparts do.

Oh, and there's no such word as "determinating," if you actually said what the transcript says you said. Duh.

Definition of "strict constructionist"

Here's a column that helps explain the understood meaning of whatever it was Scalia was trying to say. From Salon, 10/2/01:

The Wrong Man for the Job

What is a strict constructionist? President Bush used it during the last campaign, saying he would appoint strict constructionists to the Supreme Court.

Well, it generally refers to how a judge or lawyer interprets a statute or a constitution. But in 1968, candidate Nixon gave it a political meaning. Nixon said he would only appoint strict constructionists to the Supreme Court. Nixon liked to refer to former Justice Felix Frankfurter as a good example of a strict constructionist.

In theory, it means that the judge does not inject his own philosophy into interpreting the statute or constitutional provision. But as most judges, if they are candid, will tell you, this is impossible. It is a myth to believe judges can keep their personal philosophy out of their decision making. In fact, Justice Frankfurter once wrote: "The words of the Constitution are so unrestricted by their intrinsic meaning or by their history or by tradition or by prior decisions that they leave the individual justice free, if indeed they do not compel him, to gather the meaning not from reading the Constitution but from reading life."

While still at the Department of Justice, Rehnquist provided the best definition of a strict constructionist I have ever encountered. It was in a memo Rehnquist wrote while he was vetting Judge Clement Haynsworth, one of Nixon's selections who was rejected by the Senate. Rehnquist wrote, in brief, that a strict constructionist was anyone who likes prosecutors and dislikes criminal defendants and who favors civil rights defendants over civil rights plaintiffs. That is as candid and blunt as you can get. And that is the real definition of a strict constructionist.

Here's one justification for interpretating the Constitution. It's rooted in the Constitution itself—specifically, the 9th Amendment. From the Desert Dispatch:

Wednesday, March 23, 2005

COMMENTARY: Scalia and the forgotten Ninth Amendment

In a recent talk U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia criticized his fellow justices for making law, a role he believes belongs to the legislature or the people themselves. Justices, he argued, are there to interpret the Constitution, and this they must do by reading it as it was intended back when it was framed and when it was later amended. In his dissent Scalia wrote:

"The court says in so many words that what our people's laws say about the issue does not, in the last analysis, matter: 'In the end our own judgment will be brought to bear on the question of the acceptability of the death penalty. ...' The court thus proclaims itself sole arbiter of our nation's moral standards."

The charge Scalia has leveled at his colleagues — five of them, the majority who ruled for abolition of the death penalty for juveniles and the mentally impaired — is the substance of the general criticism usually labeled "judicial activism." This view decries it whenever the court rules as if there existed rights which are not explicitly mentioned or enumerated within the Constitution. One of the most famous of these unenumerated rights is the right to privacy, and the majority of the court has ruled in several recent cases that various state laws violate this right and are, therefore, unconstitutional, invalid laws.

In his recent public talk, Scalia argued that the idea of a living constitution is essentially wrongheaded because it leaves the country without a firm basis of law by which it can be governed. Instead of a stable set of constitutional principles, justices have come to make laws based on their "personal policy preferences," thus undermining the classic doctrine of the rule of law (as opposed to that of arbitrary governors).

The case Scalia makes has a good deal going for it because it is indeed part of the theory of politics in the United States that the role justices play does not include making laws, only interpreting the Constitution when some legislation is challenged through the courts (and reaches the Supreme Court). The living constitution idea is, indeed, destructive of the rule of law and of democracy itself because it encourages arbitrariness, the departure from governance by law toward governance according to the justices' own convictions.

Yet, there is a problem here because Justice Scalia ignores the Ninth Amendment to the Constitution, the one that states unequivocally that aside from rights enumerated in that document, the people have others, as well. The Ninth states that "The enumeration in this Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." So, while this does not sanction any kind of loose, "living," constitutional doctrine, it does make clear reference to rights that aren't explicitly listed in the Constitution, rights that we nonetheless possess.

What would be those rights? Pretty much to do everything and anything the government isn't authorized to prohibit. Indeed, the point of the Constitution does not appear to be to spell out our rights in particular, other than to spell out for emphasis of some of the most crucial ones. It is, rather, to state what the strictly limited powers of government are.

As to whether this authorizes the Supreme Court to strike down state and federal legislation that permits the execution of juveniles or the mentally ill, the situation is complicated. It is arguable, however, that one role of the court is to spell out the logical meanings of terms within the Constitution for our own times, meanings that have clearly undergone some rational evolution.

Just as in physics the term "atom" no longer logically means exactly what it meant 300 years ago, so in political theory and jurisprudence the term "human being" could reasonably require some updating. If it is found, for example, that children and the mentally disabled lack the full capacity of adult humans, this could reasonably require interpreting provisions of the Constitution and other laws accordingly.

And that is just what seems to lie behind recent rulings: For example, the young, who in our day aren't permitted to enter into contracts, to marry on their own, or to vote, would probably not warrant being judged guilty of crimes exactly as they were when certain nuances in understanding what human beings are had been overlooked or were not clearly understood.

Against Scalia it can be argued that although the idea of a living constitution is dangerous, so is the idea of a frozen one. Reasonable development in the meaning of the terms in the fundamental laws of the society is to be expected and should not be thwarted in the Supreme Court's deliberations and rulings. Those who protest that this is anti-democratic need to consider that the Founders were not pure democrats by a long shot — just consider the Electoral College, which is blatantly anti-democratic.

Tibor Machan

Holds the R.C. Hoiles Professorship in business ethics and free enterprise at Chapman University in Orange and is author of "Objectivity" (Ashgate). He advises Freedom Communications, parent company of this newspaper.

"Strict constructionism" = hypocrisy

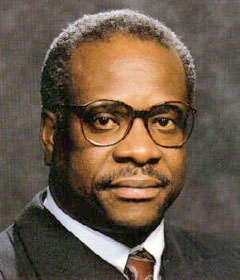

It goes without saying that Scalia and his pal Clarence Thomas are for strict constructionism except when they're against it and against judicial activism except when they're for it. In other words, they're hypocrites. An article explains how this applies to Thomas, though one could easily make the same case against Scalia.

Originalist Sins

The faux originalism of Justice Clarence Thomas.

By Doug Kendall and Jim Ryan

Posted Wednesday, Aug. 1, 2007, at 5:16 PM ET

Jan Crawford Greenburg, in her recent book Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court, has—along with several other Supreme Court commentators—demolished the once broadly held view that Justice Clarence Thomas simply follows the lead of Justice Antonin Scalia. Indeed, if Greenburg's book is to be believed, it's closer to the other way around. With this appropriate reassessment of Thomas' intellectual role on the Supreme Court, a broader claim has been advanced by his supporters that Thomas is a model originalist: a principled justice with a fixed judicial method. He is more radical than Scalia—even his supporters will admit that—but that is simply because he is so principled, they contend. Whereas Scalia will dilute his originalism with a dollop of stare decisis, Thomas likes his served straight up, even if it means upsetting decades of settled precedent.

This notion that Thomas is radical but principled is half right. To be precise, the first half is right: He is radical. But he does not seem very principled. Consider just two cases from the end of this past term, both involving public schools. One was Morse v. Frederick, the so-called "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" case, and the other was Parents Involved v. Seattle Schools, the voluntary integration case. Thomas wrote a concurring opinion in both cases. In the first, he made the bold claim that students simply do not have any right to free speech in school. Why? Because those who framed the relevant constitutional language would not have expected students to have First Amendment rights while in school.

This is an extraordinary claim for many reasons, not the least of which is the fact that public schools did not exist when the First Amendment was drafted. Even by the time the 14th Amendment was adopted, making the First Amendment applicable to the states, public schools were just getting started. Few students attended school for more than five years; public high schools were virtually nonexistent; and compulsory education was still decades away. Despite the vast differences between public education then and public education today, Justice Thomas evidently believes the question of whether students have free-speech rights should be answered by conducting an imaginary séance with 18th- and 19th-century Framers and ratifiers, who should be asked: Do you think public-school students have a constitutional right to free speech while in school? This line of inquiry is about as productive as asking an only child: Imagine you have a sister. Now, does she like cheese?

What is noteworthy in his Morse concurrence is that Justice Thomas does not ask what the language of the First Amendment means, either now, when it was originally drafted, or when it was applied against the states through the 14th Amendment. Instead, he asks how those alive at the relevant time would have applied that language to a set of facts different than we face today. This elevates the expectations of the ratifiers and Framers over the meaning of the text itself. But the meaning of the text—as Justice Thomas surely would agree—must be paramount over the subjective expectations of any individual, whether alive or dead. Indeed, it is for this very reason that even most conservatives who claim to adhere to the interpretive theory of originalism disavow the séance approach, despite continuing to practice it when convenient.

But it gets worse for Justice Thomas, considering the second school case, this one about voluntary integration. Thomas also wrote a concurring opinion in that case, in which he lambasted those who try to integrate public schools, calling school integration an elitist fad. He also claimed that using race to integrate schools was obviously unconstitutional and made an impassioned argument in favor of colorblindness—the idea that governments can never take race into account, even to protect or assist minorities.

But guess what's missing entirely from this sweeping opinion? That's right: any consideration, whatsoever, of how the Framers and ratifiers of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment would have viewed voluntary integration of public schools. The touchstone originalism of his Morse opinion is nowhere to be found.

It may be too much to expect any individual justice to be perfectly consistent from year to year and across a diverse array of cases. But here we have two public-school cases, both involving the rights of students, and both decided within days of each other, with Justice Thomas writing concurring opinions in each case, concurrences that no other justices joined. Don't you think that someone, somewhere, might have asked Thomas: "Um, so you ask what the Framers would have thought about speech in school but not what they would have thought about voluntary integration. Why not?"

Here's our guess: The question is not asked because it does not yield an answer Justice Thomas would like. There is no way to make an argument, at least with a straight face, that the 14th Amendment was originally understood to prohibit voluntary school integration. No way. Indeed, given how flimsy the evidence is for Justice Thomas' other argument—that students have no free-speech rights in school—it's clear that he is not shy about stitching together a historical tale from very slim pieces of material. The fact that he doesn't even try to make the historical case in the voluntary integration decision speaks volumes.

What it says is that Justice Thomas is not particularly principled. To be clear, this is not a criticism of Thomas as a person. We're not saying that he's mean or doesn't like dogs or small children. We're criticizing his work, much in the same way Scalia recently criticized Chief Justice John Roberts for his "faux" judicial restraint. Our criticism is similar: Justice Thomas is not sticking with his professed commitment to originalism, and is certainly not living up to his newfound reputation as the high priest of principled originalism.

His recent opinions instead suggest that Thomas will use originalism where it provides support for a politically conservative result, even if that support is weak, as it is in the student-speech case. But where history provides no support, he's likely to ignore it altogether. If his cheerleaders believe otherwise, they should try to reconcile his opinions in the two school cases on originalist grounds.

While they are at it, they might also try to explain a third case from the end of this past term: FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life. This was also a free-speech case, decided the same day as the student-speech case. This case dealt with provisions of the McCain-Feingold Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, a law that regulates issue ads paid for by corporations and unions. Unlike public schools, corporations did exist when the Constitution was originally ratified, and through the opinions of Chief Justice John Marshall, we have a pretty good idea about how the Framing generation tended to view corporations: They are, in Marshall's words: "an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of the law."

In 1990, the Supreme Court in Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce echoed Marshall's views by concluding that "the unique state-conferred corporate structure that facilitates the amassing of large treasuries warrants the limit on independent expenditures [by corporations]." Nonetheless, after concluding in Morse that students in public school have no free-speech rights, Thomas joined an opinion by Scalia calling Austin "wrongly decided" and endorsing the proposition that corporations should have precisely the same speech rights as individuals. Again, there was no inquiry into original understanding, no Morse-like probe into what the Framers would have wished.

For someone lauded as the originalist's originalist, this is a pretty weak showing. For someone looking to advance a conservative political agenda, however, these three cases constitute a sort of trifecta: Curtail voluntary integration and student rights while boosting the rights of corporations. Not a bad couple of weeks.

There is a lesson here for liberals. In two of the three most important cases of the past term, Thomas was forced to abandon originalism—his version of it, anyway—in order to reach a politically conservative result. In the other, his originalist reasoning was weak at best. What this suggests is that, contrary to conventional wisdom, originalism may not be co-extensive with the Republican Party platform after all. It also suggests, as we've written elsewhere, that liberals ought to begin to take a closer look at text and history themselves.

Doug Kendall is founder and executive director of Community Rights Counsel, a public interest law firm in Washington, D.C.

Jim Ryan is the academic associate dean and William L. Matheson and Robert M. Morgenthau distinguished professor at the University of Virginia School of Law.

Copyright 2007 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Treasonous, corrupt, or merely stupid?

Let's move on to the issue that put Scalia's bias in the international spotlight: the 2000 election. Here's what the experts thought about his performance (imagine a circus clown). First, from a book review of Supreme Injustice: How the High Court Hijacked Election 2000 by Alan M. Dershowitz:

According to Dershowitz, Scalia violated his judicial philosophy because wanted to make sure his boy got in. He succeeded, but — Dershowitz argues — at the cost of his honor and his reputation: "Had he passed the test posed by this case, history might well have remembered him as the man of principle he claims to be. But he failed the test, and failed it badly ... Scalia's vote in Bush v. Gore has shown that the most accurate guide to predicting his judicial decisions is to follow his political and personal preferences rather than his lofty rhetoric about judicial restraint, originalism, and other abstract aspects of his so-called constraining judicial philosophy, which turns out to be little more than a cover for his politics and his desire to pack the Court with like-minded justices."

That's bad enough, but some think Scalia did far worse. From a book review of The Betrayal of America: How the Supreme Court Undermined the Constitution and Chose Our President by Vincent Bugliosi:

[Bugliosi] argues that in stopping the Florida recount and effectively handing the election to George W. Bush (which was clearly, he claims, their intent), the five conservative justices engaged in criminal conduct bordering on treason. Bugliosi claims that the only reason their action isn't legally treason is that Congress "never dreamed of enacting a statute making it a crime to steal a presidential election."

Bugliosi sets about proving his case with a lethal focus. Part of that focus requires dispensing with what he considers irrelevancies, chief among them the question of whether it was Bush or Gore who actually got more votes in Florida. Whoever won the state, Bugliosi argues, has no bearing on the legal, ethical and moral culpability of the justices' actions.

All those in favor of treason charges, or at least impeachment, say aye. Aye!

Final answer?

Long after the election was over, a media group did a comprehensive analysis of Florida's ballots. Many newspapers characterized the results as "Bush would've won anyway." Some comments on this spin from the letters to the LA Times, 11/13/01:

Ballot-Count Scenarios in Bush-Gore 2000

Even if true—and a careful reading of the article shows that Al Gore could just as well have won—in no way does this right the wrongs committed by the U.S. Supreme Court on Dec. 9. Halting the recounts, as Justice Antonin Scalia did, was wrong both morally and legally. The right approach would have been to allow the recounts to continue, then rule later on their validity as evidence (which courts do all the time).

Of course, Scalia should not have intervened at all. As in the 1824 and 1876 elections, Congress alone should have resolved a disputed presidential election. This is what the Constitution mandates; the Supreme Court has no jurisdiction. What distresses me the most is that so many people say that Bush might have won anyway, and he's doing a decent job, so everything's fine. This "results trump process" approach, taken to its logical conclusion, means that we should dispense with future elections and just let the Supreme Court wisely appoint our leaders for us. Democracy in action, eh?

Thomas E. Braun

Palmdale

More people in Florida tried to vote for Gore than Bush; if some of Bush's rules were followed, Gore would have won; if Gore's rules were followed, Bush would have won; in eight different recount scenarios examined by the National Opinion Research Center, Gore would have won in four and Bush would have won in four.

None of these facts justifies the headline, "Bush Still Had Votes to Win in a Recount, Study Finds," an assertion immediately contradicted by the subheadline, "An exhaustive ballot review indicates more people tried to vote for Gore, and he might have won had pending reforms been in effect."

This does seem to be a case of bias, albeit in the opposite direction from that decried by most media critics. Perhaps the left-leaning, liberal press has diabolically disguised itself as pro-Republican.

Of course, all of this would be moot if there was serious consideration being given to abolishing the electoral college, since Gore decidedly won the national popular vote. But then, why should we in California complain that each of our votes counts only half as much as votes cast in New Mexico?

Brad Goldberg

Studio City

More on Scalia and other activist judges

Commentary

MICHAEL KINSLEY

Who Are the Activists Now?

Judges that rule for Bush escape that nasty label.

Los Angeles Times (CA)

November 14, 2004

What does President Bush mean, if anything, when he says that his kind of judge "knows the difference between personal opinion and the strict interpretation of the law"? Every judge sincerely believes that he or she is interpreting the law properly.

Bush's complaint must be understood in the context of Republican Party history over the last half-century. Ever since Chief Justice Earl Warren and Brown vs. Board of Education (the 1954 school desegregation case), conservatives have complained about "activist" judges and justices who allegedly imposed their own liberal dictates on the country with no legal basis. Taking up this rallying cry is one way Republicans won the South. Even Southern conservatives don't publicly complain about Brown anymore, of course. But denouncing activist judges is now Republican boilerplate.

Judges make decisions and impose their will all the time. That's their job. When does this generally salutary activity turn into the dread judicial activism? If activism has any specific meaning, it means judges overruling laws and policies put in place by the democratically elected branches of government. It also refers to federal judges overruling policies enacted by the individual states.

George W. Bush may get to appoint as many as four Supreme Court justices, including the chief. But the complaint about liberal activism has been quaint for decades. All three chief justices since the "activism" fuss began were appointed by Republican presidents. Earl Warren, it's true, was a bitter surprise to Republicans, but Warren E. Burger was not, and William H. Rehnquist was a positive delight. Liberal judicial activism peaked with Roe vs. Wade, the 1973 abortion decision (which Burger supported), and has been in retreat now for longer than it lasted.

Complaints about judicial activism are a habit left over from powerlessness. They seem especially retro when held up against today's ambitious Republican judicial agenda. With one apparent exception, the major items on it are demands for federal judges to override Congress or states' rights. Republicans cheer, for example, when courts overturn state or federal — or even private — affirmative action programs, and they boo when such programs are allowed to continue unmolested. They have great hopes — largely unrealized, so far — for the "takings" clause of the 5th Amendment as a tool for overturning environmental regulations or any other government policies that may reduce the value of someone's property.

There is even a move afoot in the Senate to have Democratic filibusters against Bush's judicial nominees ruled unconstitutional. That would be activism squared.

And let's not forget that the Bush administration owes its very existence to the boldest act of judicial activism in a generation: the Supreme Court ruling that settled the 2000 presidential election dispute. Bush vs. Gore made imaginative use of the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause to reverse the Florida Supreme Court's interpretation of its own election laws.

Republicans will protest, sincerely if not always correctly, that these examples are all legitimate interpretations of the Constitution and not just invitations for judges to take a power trip. But that's the point. One person's constitutional interpretation is another person's judicial rampage. Neither party has a magic formula for determining which is which, and, in practice, neither has been able to resist trying to enact its agenda through judicial fiat when it gets the chance.

The apparent exception to the activist nature of the Republican judicial wish list is abortion. Although I am pro-choice, I was taught in law school, and still believe, that Roe vs. Wade is a muddle of bad reasoning and an authentic example of judicial overreaching. I also believe it was a political disaster for liberals. Roe is what first politicized religious conservatives (while cutting off a political process that was legalizing abortion state by state anyway). Three decades later, that awakened giant controls the government.

But has anybody read the 2004 Republican platform on abortion? It doesn't merely call for reversal of Roe vs. Wade. It calls for "legislation to make it clear that the 14th Amendment's protections apply to unborn children," and for judges who believe likewise. How's that for activism? If fetuses are "persons" under the 14th amendment, which guarantees all persons "equal protection of the law," abortion would be illegal whether a state or the Congress wanted to keep it legal it or not. More than that: There could be no legal distinction between the rights of fetuses and the rights of human beings after birth. So, just for example, a woman who procured an abortion would have to be prosecuted as if she had hired a gunman to murder her child. The doctor would have to be treated like the gunman. And that includes capital punishment in states that have it. And the party that now controls all three branches of government says this is already the case. Only legislation is needed to "make it clear," and judges are needed who will enforce it.

But no "activism," please. The Republican Party can't stand that.

Copyright 2004 Los Angeles Times

Proof that conservatives are activists

From the NY Times:

July 6, 2005

So Who Are the Activists?

By PAUL GEWIRTZ and CHAD GOLDER

Correction Appended

New Haven

WHEN Democrats or Republicans seek to criticize judges or judicial nominees, they often resort to the same language. They say that the judge is "activist." But the word "activist" is rarely defined. Often it simply means that the judge makes decisions with which the critic disagrees.

In order to move beyond this labeling game, we've identified one reasonably objective and quantifiable measure of a judge's activism, and we've used it to assess the records of the justices on the current Supreme Court.

Here is the question we asked: How often has each justice voted to strike down a law passed by Congress?

Declaring an act of Congress unconstitutional is the boldest thing a judge can do. That's because Congress, as an elected legislative body representing the entire nation, makes decisions that can be presumed to possess a high degree of democratic legitimacy. In an 1867 decision, the Supreme Court itself described striking down Congressional legislation as an act "of great delicacy, and only to be performed where the repugnancy is clear." Until 1991, the court struck down an average of about one Congressional statute every two years. Between 1791 and 1858, only two such invalidations occurred.

Of course, calling Congressional legislation into question is not necessarily a bad thing. If a law is unconstitutional, the court has a responsibility to strike it down. But a marked pattern of invalidating Congressional laws certainly seems like one reasonable definition of judicial activism.

Since the Supreme Court assumed its current composition in 1994, by our count it has upheld or struck down 64 Congressional provisions. That legislation has concerned Social Security, church and state, and campaign finance, among many other issues. We examined the court's decisions in these cases and looked at how each justice voted, regardless of whether he or she concurred with the majority or dissented.

We found that justices vary widely in their inclination to strike down Congressional laws. Justice Clarence Thomas, appointed by President George H. W. Bush, was the most inclined, voting to invalidate 65.63 percent of those laws; Justice Stephen Breyer, appointed by President Bill Clinton, was the least, voting to invalidate 28.13 percent. The tally for all the justices appears below.

Thomas 65.63 %

Kennedy 64.06 %

Scalia 56.25 %

Rehnquist 46.88 %

O'Connor 46.77 %

Souter 42.19 %

Stevens 39.34 %

Ginsburg 39.06 %

Breyer 28.13 %

One conclusion our data suggests is that those justices often considered more "liberal" -- Justices Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, David Souter and John Paul Stevens -- vote least frequently to overturn Congressional statutes, while those often labeled "conservative" vote more frequently to do so. At least by this measure (others are possible, of course), the latter group is the most activist.

To say that a justice is activist under this definition is not itself negative. Because striking down Congressional legislation is sometimes justified, some activism is necessary and proper. We can decide whether a particular degree of activism is appropriate only by assessing the merits of a judge's particular decisions and the judge's underlying constitutional views, which may inspire more or fewer invalidations.

Our data no doubt reflects such differences among the justices' constitutional views. But it even more clearly illustrates the varying degrees to which justices would actually intervene in the democratic work of Congress. And in so doing, the data probably demonstrates differences in temperament regarding intervention or restraint.

These differences in the degree of intervention and in temperament tell us far more about "judicial activism" than we commonly understand from the term's use as a mere epithet. As the discussion of Justice Sandra Day O'Connor's replacement begins, we hope that debates about "activist judges" will include indicators like these.

Correction

Because of an editing error, this article misstated the date the court started. Its first official business began in 1790, not 1791.

Paul Gewirtz is a professor at Yale Law School. Chad Golder graduated from Yale Law School in May.

What "activist judge" really means

From the NY Times:

April 24, 2005

OP-ED COLUMNIST

A High-Tech Lynching in Prime Time

By FRANK RICH

Whatever your religious denomination, or lack of same, it was hard not to be swept up in last week's televised pageantry from Rome: the grandeur of St. Peter's Square, the panoply of the cardinals, the continuity of history embodied by the joyous emergence of the 265th pope. As a show of faith, it's a tough act to follow. But that has not stopped some ingenious American hucksters from trying.

Tonight is the much-awaited "Justice Sunday," the judge-bashing rally being disseminated nationwide by cable, satellite and Internet from a megachurch in Louisville. It may not boast a plume of smoke emerging from above the Sistine Chapel, but it will feature its share of smoke and mirrors as well as traditions that, while not dating back a couple of millenniums, do at least recall the 1920's immortalized in "Elmer Gantry." These traditions have less to do with the earnest practice of religion by an actual church, as we witnessed from Rome, than with the exploitation of religion by political operatives and other cynics with worldly ends. While Sinclair Lewis wrote that Gantry, his hypocritical evangelical preacher, "was born to be a senator," we now have senators who are born to be Gantrys. One of them, the Senate majority leader, Bill Frist, hatched plans to be beamed into tonight's festivities by videotape, a stunt that in itself imbues "Justice Sunday" with a touch of all-American spectacle worthy of "The Wizard of Oz."

Like the wizard himself, "Justice Sunday" is a humbug, albeit one with real potential consequences. It brings mass-media firepower to a campaign against so-called activist judges whose virulence increasingly echoes the rhetoric of George Wallace and other segregationists in the 1960's. Back then, Wallace called for the impeachment of Frank M. Johnson Jr., the federal judge in Alabama whose activism extended to upholding the Montgomery bus boycott and voting rights march. Despite stepped-up security, a cross was burned on Johnson's lawn and his mother's house was bombed.

The fraudulence of "Justice Sunday" begins but does not end with its sham claims to solidarity with the civil rights movement of that era. "The filibuster was once abused to protect racial bias," says the flier for tonight's show, "and now it is being used against people of faith." In truth, Bush judicial nominees have been approved in exactly the same numbers as were Clinton second-term nominees. Of the 13 federal appeals courts, 10 already have a majority of Republican appointees. So does the Supreme Court. It's a lie to argue, as Tom DeLay did last week, that such a judiciary is the "left's last legislative body," and that Justice Anthony Kennedy, a Reagan appointee, is the poster child for "outrageous" judicial overreach. Our courts are as highly populated by Republicans as the other two branches of government.

The "Justice Sunday" mob is also lying when it claims to despise activist judges as a matter of principle. Only weeks ago it was desperately seeking activist judges who might intervene in the Terri Schiavo case as boldly as Scalia & Co. had in Bush v. Gore. The real "Justice Sunday" agenda lies elsewhere. As Bill Maher summed it up for Jay Leno on the "Tonight" show last week: " 'Activist judges' is a code word for gay." The judges being verbally tarred and feathered are those who have decriminalized gay sex (in a Supreme Court decision written by Justice Kennedy) as they once did abortion and who countenance marriage rights for same-sex couples. This is the animus that dares not speak its name tonight. To paraphrase the "Justice Sunday" flier, now it's the anti-filibuster campaign that is being abused to protect bias, this time against gay people.

Anyone who doesn't get with this program, starting with all Democrats, is damned as a bigoted enemy of "people of faith." But "people of faith," as used by the event's organizers, is another duplicitous locution; it's a code word for only one specific and exclusionary brand of Christianity. The trade organization representing tonight's presenters, National Religious Broadcasters, requires its members to "sign a distinctly evangelical statement of faith that would probably exclude most Catholics and certainly all Jewish, Muslim or Buddhist programmers," according to the magazine Broadcasting & Cable. The only major religious leader involved with "Justice Sunday," R. Albert Mohler Jr. of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, has not only called the papacy a "false and unbiblical office" but also told Terry Gross on NPR two years ago that "any belief system" leading "away from the cross of Christ and toward another way of ultimate meaning, is, indeed, wicked and evil."

Tonight's megachurch setting and pseudoreligious accouterments notwithstanding, the actual organizer of "Justice Sunday" isn't a clergyman at all but a former state legislator and candidate for insurance commissioner in Louisiana, Tony Perkins. He now runs the Family Research Council, a Washington propaganda machine devoted to debunking "myths" like "People are born gay" and "Homosexuals are no more likely to molest children than heterosexuals are." It will give you an idea of the level of Mr. Perkins's hysteria that, as reported by The American Prospect, he told a gathering in Washington this month that the judiciary poses "a greater threat to representative government" than "terrorist groups." And we all know the punishment for terrorists. Accordingly, Newsweek reports that both Justices Kennedy and Clarence Thomas have "asked Congress for money to add 11 police officers" to the Supreme Court, "including one new officer just to assess threats against the justices." The Judicial Conference of the United States, the policy-making body for the federal judiciary, has requested $12 million for home-security systems for another 800 judges.

Mr. Perkins's fellow producer tonight is James Dobson, the child psychologist who created Focus on the Family, the Colorado Springs media behemoth most famous of late for condemning SpongeBob SquarePants for joining other cartoon characters in a gay-friendly public-service "We Are Family" video for children. Dr. Dobson sees same-sex marriage as the path to "marriage between a man and his donkey" and, in yet another perversion of civil rights history, has likened the robed justices of the Supreme Court to the robed thugs of the Ku Klux Klan. He has promised "a battle of enormous proportions from sea to shining sea" if he doesn't get the judges he wants.

Once upon a time you might have wondered what Senator Frist is doing lighting matches in this tinderbox. As he never ceases to remind us, he is a doctor -- an M.D., not some mere Ph.D. like Dr. Dobson -- with an admirable history of combating AIDS in Africa. But this guy signed his pact with the devil even before he decided to grandstand in the Schiavo case by besmirching the diagnoses of neurologists who, unlike him, had actually examined the patient.

It was three months earlier, on the Dec. 5, 2004, edition of ABC News's "This Week With George Stephanopoulos," that Dr. Frist enlisted in the Perkins-Dobson cavalry. That week Bush administration abstinence-only sex education programs had been caught spreading bogus information, including the canard that tears and sweat can transmit H.I.V. and AIDS -- a fiction that does nothing to further public health but is very effective at provoking the demonization of gay men and any other high-risk group for the disease. Asked if he believed this junk science was true, the Princeton-and-Harvard-educated Dr. Frist said, "I don't know." After Mr. Stephanopoulos pressed him three more times, this fine doctor theorized that it "would be very hard" for tears and sweat to spread AIDS (still a sleazy answer, since there have been no such cases).

Senator Frist had hoped to deflect criticism of his cameo on "Justice Sunday" by confining his appearance to video. Though he belittled the disease-prevention value of condoms in that same "This Week" interview, he apparently now believes that videotape is just the prophylactic to shield him from the charge that he is breaching the wall separating church and state. His other defense: John Kerry spoke at churches during the presidential campaign. Well, every politician speaks at churches. Not every political leader speaks at nationally televised political rallies that invoke God to declare war on courts of law.

Perhaps the closest historical antecedent of tonight's crusade was that staged in the 1950's and 60's by a George Wallace ally, the televangelist Billy James Hargis. At its peak, his so-called Christian Crusade was carried by 500 radio stations and more than 200 television stations. In the "Impeach Earl Warren" era, Hargis would preach of the "collapse of moral values" engineered by a "powerfully entrenched, anti-God Liberal Establishment." He also decried any sex education that talked about homosexuality or even sexual intercourse. Or so he did until his career was ended by accusations that he had had sex with female students at the Christian college he founded as well as with boys in the school's All-American Kids choir.

Hargis died in obscurity the week before Dr. Frist's "This Week" appearance. But no less effectively than the cardinals in Rome, he has passed the torch.

Related links

The Founders' original intent

A well regulated militia...

America the conservative

Right-wing extremists: the enemy within

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.