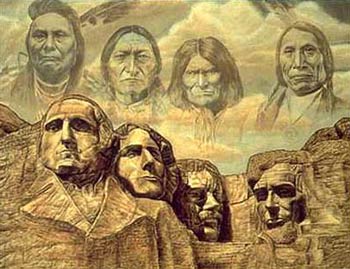

In which Teddy Roosevelt admits it was US policy to kill or conquer the Indians and take their land. Featuring selected quotes from Roosevelt's The Winning of the West, Volume Three: The Founding of the Trans-Alleghany Commonwealths, 1784-1790:

In which Teddy Roosevelt admits it was US policy to kill or conquer the Indians and take their land. Featuring selected quotes from Roosevelt's The Winning of the West, Volume Three: The Founding of the Trans-Alleghany Commonwealths, 1784-1790: In which Teddy Roosevelt admits it was US policy to kill or conquer the Indians and take their land. Featuring selected quotes from Roosevelt's The Winning of the West, Volume Three: The Founding of the Trans-Alleghany Commonwealths, 1784-1790:

In which Teddy Roosevelt admits it was US policy to kill or conquer the Indians and take their land. Featuring selected quotes from Roosevelt's The Winning of the West, Volume Three: The Founding of the Trans-Alleghany Commonwealths, 1784-1790:

The War Inevitable.

In truth the war was unavoidable. The claims and desires of the two parties were irreconcilable. Treaties and truces were palliatives which did not touch the real underlying trouble. The white settlers were unflinchingly bent on seizing the land over which the Indians roamed but which they did not in any true sense own or occupy. In return the Indians were determined at all costs and hazards to keep the men of chain and compass, and of axe and rifle, and the forest-felling settlers who followed them, out of their vast and lonely hunting-grounds. Nothing but the actual shock of battle could decide the quarrel. The display of overmastering, overwhelming force might have cowed the Indians; but it was not possible for the United States, or for any European power, ever to exert or display such force far beyond the limits of the settled country. In consequence the warlike tribes were not then, and never have been since, quelled save by actual hard fighting, until they were overawed by the settlement of all the neighboring lands.

Nor was there any alternative to these Indian wars. It is idle folly to speak of them as being the fault of the United States Government; and it is even more idle to say that they could have been averted by treaty. Here and there, under exceptional circumstances or when a given tribe was feeble and unwarlike, the whites might gain the ground by a treaty entered into of their own free will by the Indians, without the least duress; but this was not possible with warlike and powerful tribes when once they realized that they were threatened with serious encroachment on their hunting-grounds. Moreover, looked at from the standpoint of the ultimate result, there was little real difference to the Indian whether the land was taken by treaty or by war. In the end the Delaware fared no better at the hands of the Quaker than the Wampanoag at the hands of the Puritan; the methods were far more humane in the one case than in the other, but the outcome was the same in both. No treaty could be satisfactory to the whites, no treaty served the needs of humanity and civilization, unless it gave the land to the Americans as unreservedly as any successful war.

Our Dealings with the Indians.

As a matter of fact, the lands we have won from the Indians have been won as much by treaty as by war; but it was almost always war, or else the menace and possibility of war, that secured the treaty. In these treaties we have been more than just to the Indians; we have been abundantly generous, for we have paid them many times what they were entitled to; many times what we would have paid any civilized people whose claim was as vague and shadowy as theirs. By war or threat of war, or purchase we have won from great civilized nations, from France, Spain, Russia, and Mexico, immense tracts of country already peopled by many tens of thousands of families; we have paid many millions of dollars to these nations for the land we took; but for every dollar thus paid to these great and powerful civilized commonwealths, we have paid ten, for lands less valuable, to the chiefs and warriors of the red tribes. No other conquering and colonizing nation has ever treated the original savage owners of the soil with such generosity as has the United States. Nor is the charge that the treaties with the Indians have been broken, of weight in itself; it depends always on the individual case. Many of the treaties were kept by the whites and broken by the Indians; others were broken by the whites themselves; and sometimes those who broke them did very wrong indeed, and sometimes they did right. No treaties, whether between civilized nations or not, can ever be regarded as binding in perpetuity; with changing conditions, circumstances may arise which render it not only expedient, but imperative and honorable, to abrogate them.

Necessity of the Conquest.

Whether the whites won the land by treaty, by armed conquest, or, as was actually the case, by a mixture of both, mattered comparatively little so long as the land was won. It was all-important that it should be won, for the benefit of civilization and in the interests of mankind. It is indeed a warped, perverse, and silly morality which would forbid a course of conquest that has turned whole continents into the seats of mighty and flourishing civilized nations. All men of sane and wholesome thought must dismiss with impatient contempt the plea that these continents should be reserved for the use of scattered savage tribes, whose life was but a few degrees less meaningless, squalid, and ferocious than that of the wild beasts with whom they held joint ownership. It is as idle to apply to savages the rules of international morality which obtain between stable and cultured communities, as it would be to judge the fifth-century English conquest of Britain by the standards of today. Most fortunately, the hard, energetic, practical men who do the rough pioneer work of civilization in barbarous lands, are not prone to false sentimentality. The people who are, are the people who stay at home. Often these stay-at-homes are too selfish and indolent, too lacking in imagination, to understand the race-importance of the work which is done by their pioneer brethren in wild and distant lands; and they judge them by standards which would only be applicable to quarrels in their own townships and parishes. Moreover, as each new land grows old, it misjudges the yet newer lands, as once it was itself misjudged. The home-staying Englishman of Britain grudges to the Africander his conquest of Matabeleland; and so the home-staying American of the Atlantic States dislikes to see the western miners and cattlemen win for the use of their people the Sioux hunting-grounds. Nevertheless, it is the men actually on the borders of the longed-for ground, the men actually in contact with the savages, who in the end shape their own destinies.

Righteousness of the War.

The most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages, though it is apt to be also the most terrible and inhuman. The rude, fierce settler who drives the savage from the land lays all civilized mankind under a debt to him. American and Indian, Boer and Zulu, Cossack and Tartar, New Zealander and Maori,—in each case the victor, horrible though many of his deeds are, has laid deep the foundations for the future greatness of a mighty people. The consequences of struggles for territory between civilized nations seem small by comparison. Looked at from the standpoint of the ages, it is of little moment whether Lorraine is part of Germany or of France, whether the northern Adriatic cities pay homage to Austrian Kaiser or Italian King; but it is of incalculable importance that America, Australia, and Siberia should pass out of the hands of their red, black, and yellow aboriginal owners, and become the heritage of the dominant world races.

Horrors of the War.

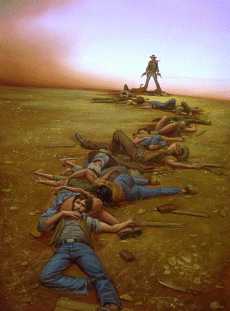

Yet the very causes which render this struggle between savagery and the rough front rank of civilization so vast and elemental in its consequence to the future of the world, also tend to render it in certain ways peculiarly revolting and barbarous. It is primeval warfare, and it is waged as war was waged in the ages of bronze and of iron. All the merciful humanity that even war has gained during the last two thousand years is lost. It is a warfare where no pity is shown to non-combatants, where the weak are harried without ruth, and the vanquished maltreated with merciless ferocity. A sad and evil feature of such warfare is that the whites, the representatives of civilization, speedily sink almost to the level of their barbarous foes, in point of hideous brutality. The armies are neither led by trained officers nor made up of regular troops—they are composed of armed settlers, fierce and wayward men, whose ungovernable passions are unrestrained by discipline, who have many grievous wrongs to redress, and who look on their enemies with a mixture of contempt and loathing, of dread and intense hatred. When the clash comes between these men and their sombre foes, too often there follow deeds of enormous, of incredible, of indescribable horror. It is impossible to dwell without a shudder on the monstrous woe and misery of such a contest.

The Indians.

In their paint and their cheap, dirty finery, these savages did not look very important; yet it was because of them that the British kept up their posts in these far-off forests, beside these great lonely waters; it was for their sakes that they tried to stem the inrush of the settlers of their own blood and tongue; for it was their presence alone which served to keep the wilderness as a game preserve for the fur merchants; it was their prowess in war which prevented French village and British garrison from being lapped up like drops of water before the fiery rush of the American advance. The British themselves, though fighting with and for them, loved them but little; like all frontiersmen, they soon grew to look down on their mean and trivial lives,—lives which nevertheless strongly attracted white men of evil and shiftless, but adventurous, natures, and to which white children, torn from their homes and brought up in the wigwams, became passionately attached. Yet back of the lazy and drunken squalor lay an element of the terrible, all the more terrible because it could not be reckoned with. Dangerous and treacherous allies, upon whom no real dependence could ever placed, the Indians were nevertheless the most redoubtable of all foes when the war was waged in their own gloomy woodlands.

But bands of young braves from all the tribes began to cross the Ohio, and ravage the settlements, from the Pennsylvania frontier to Kentucky. They stole horses, burned houses, and killed or carried into a dreadful captivity men, women, and children. The inroads were as usual marked by stealth, rapine, and horrible cruelty. It is hard for those accustomed only to treat of civilized warfare to realize the intolerable nature of these ravages, the fact that the loss and damage to the whites was out of all proportion to the strength of the Indian war parties, and the extreme difficulty in dealing an effective counter stroke.

In spite of the counter strokes of the wild wood-rangers, the Indian ravages speedily wrapped the frontier in fire and blood.

The ravages committed by these skulking parties of murderous braves were monotonous in their horror. All along the frontier the people on the outlying farms were ever in danger, and there was risk for the small hamlets and block-houses. In their essentials the attacks were alike: the stealthy approach, the sudden rush, with its accompaniment of yelling war-whoops, the butchery of men, women, and children, and the hasty flight with whatever prisoners were for the moment spared, before the armed neighbors could gather for rescue and revenge.

More of Roosevelt on Indians

During the past century a good deal of sentimental nonsense has been talked about our taking the Indians' land. Now, I do not mean to say for a moment that gross wrong has not been done the Indians, both by government and individuals, again and again. The government makes promises impossible to perform, and then fails to do even what it might toward their fulfilment; and where brutal and reckless frontiersmen are brought into contact with a set of treacherous, revengeful, and fiendishly cruel savages a long series of outrages by both sides is sure to follow. But as regards taking the land, at least from the western Indians, the simple truth is that the latter never had any real ownership in it at all. Where the game was plenty, there they hunted; they followed it when it moved away to new hunting-grounds, unless they were prevented by stronger rivals; and to most of the land on which we found them they had no stronger claim than that of having a few years previously butchered the original occupants. When my cattle came to the Little Missouri the region was only inhabited by a score or so of white hunters; their title to it was quite as good as that of most Indian tribes to the lands they claim; yet nobody dreamed of saying that these hunters owned the country. Each could eventually have kept his own claim of 160 acres, and no more. The Indians should be treated in just the same way that we treat the white settlers. Give each his little claim; if, as would generally happen, he declined this, why then let him share the fate of the thousands of white hunters and trappers who have lived on the game that the settlement of the country has exterminated, and let him, like these whites, who will not work, perish from the face of the earth which he cumbers.

The doctrine seems merciless, and so it is; but it is just and rational for all that. It does not do to be merciful to a few, at the cost of justice to the many. The cattle-men at least keep herds and build houses on the land; yet I would not for a moment debar settlers from the right of entry to the cattle country, though their coming in means in the end the destruction of us and our industry.

Theodore Roosevelt, Chapter I: Ranching in the Bad Lands, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, 1885

I suppose I should be ashamed to say that I take the Western view of the Indian. I don't go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every ten are, and I shouldn't like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth. The most vicious cowboy has more moral principle than the average Indian. Turn three hundred low families of New York into New Jersey, support them for fifty years in vicious idleness, and you will have some idea of what the Indians are. Reckless, revengeful, fiendishly cruel, they rob and murder, not the cowboys, who can take care of themselves, but the defenseless, lone settlers on the plains. As for the soldiers, an Indian chief once asked Sheridan for a cannon. "What! Do you want to kill my soldiers with it?" asked the general. "No," replied the chief, "want to kill the cowboy; kill soldier with a club."

Theodore Roosevelt, speech, January 1886

Rob's comment

Roosevelt's The Winning of the West contains several false or unsupported claims. Among them:

His claim in Hunting Trips of a Ranchman is also problematical. The "western" (i.e. Plains) Indians may have been nomadic, but what about all the Indians west of the Rockies and east of the Mississippi? What is Roosevelt's rationale for taking their land?

In Hunting Trips Roosevelt doesn't offer a rationale, but you can imagine what he'd say. He made it clear in The Winning of the West that any excuse would suffice. If the Indians were nomadic, they didn't own the land. If they were settled, they didn't deserve the land. If they signed treaties giving them legal ownership, the US had the right to abrogate the treaties whenever circumstances changed.

Can you say "sophistry"? Roosevelt may think his reasoning is "rational," but it has no logical basis. The only basis evident is "White Makes Might Makes Right."

More on Roosevelt's racism

Iraq: Is It All the Indians' Fault?

Adventurer Africa

Related links

Mark Twain, Indian hater

Uncivilized Indians

Savage Indians

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.