Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

Red·skin n. Dated, Offensive, Taboo

(7/14/02)

Main Entry: red·skin

Pronunciation: 'red-"skin

Function: noun

Date: 1699

usually offensive : AMERICAN INDIAN

Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary

redskin

noun [C]

TABOO DATED

a Native American

Cambridge International Dictionary of English

red·skin

n. Offensive Slang

Used as a disparaging term for a Native American.

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition

*****

The evidence against "redskin"

Harjo: Dirty word games

Posted: June 17, 2005

by: Suzan Shown Harjo / Indian Country Today

Only a few wounding words carry pain so severe that they are not dulled by time. "Redskins" is such a word for most Native people. Once you've been stung by that word, you never, ever forget it or the venom of each modifier, most commonly "dirty," "lazy" and "stupid."

Manley A. Begay Jr. was "about seven or eight years" when he was hit with the R-word by a non-Indian in his own Navajo land in Arizona: "'You dirty redskin, you stinky redskin, you dirty Indian, go back to your hogan.'

"And he kept on repeating that, you know, and yelling and screaming at me and making these racist and insulting and degrading remarks: you stinky redskin ... you stupid redskin."

Norbert S. Hill Jr., who is Oneida from Wisconsin, was called the R-word during a high school football game. "I remember tackling ... a conference top player for a two-yard loss, and he called me a 'dirty f***ing redskin."

William A. Means Jr. was "applying for a job to make hay" when a "white rancher" referred to him "as a redskin." Means, who is Oglala Lakota from South Dakota, then "felt prejudice, intimidation, so I left."

Begay, Hill and Means went on to run Indian education programs and schools, and to sue the Washington professional football team regarding its dreadful name.

Their statements are evidence in the lawsuit, Harjo et al v. Pro Football, Inc., now in its 13th year of litigation.

We won the case in 1999, when three trademark judges unanimously canceled the federal licenses for the Washington football club's name "on the grounds that the subject marks may disparage Native Americans and may bring them into contempt or disrepute."

A federal district court judge, without so much as a hearing, overturned their decision in 2003, opining that the trademark judges got it wrong. We appealed the 2003 ruling and expect a decision any day from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Our other co-plaintiffs are Vine Deloria Jr., Standing Rock Sioux author, lawyer and retired educator; Raymond D. Apodaca, a former tribal leader of his Tigua Tribe in Texas and now a federal Indian program official; and Mateo Romero, a Cochiti Pueblo artist in New Mexico.

Deloria testified that in Marine boot camp "they would just blast the hell out of everybody, using 'nigger' and 'spic' and 'slope' and 'redskin."' Apodaca recalled remarks about the "noisy and obnoxious redskins." Romero stated that "the term 'nigger,' like 'redskin,' is racial."

It's hard to understand how the federal district court judge could substitute her opinion for the judgment of the three trademark judges -- and for our actual experience -- and say we aren't disparaged.

The judge also thought we waited too long to bring the suit, saying we should have filed in 1967 when the Washington football club first applied for federal trademark protection. At that time, only one of the seven of us was 21 years old and Romero wasn't even a toddler.

The judge said nothing about the fact that the football owners waited more than 30 years before seeking a federal license. In all likelihood, they were prompted to file for federal protection in the 1960s by protesters on campuses nationwide who wanted to end "Native" sports references and cited the Washington "Redskins" as the worst of all.

Among the mountain of evidence considered by the trademark judges over the first seven years of litigation were examples of the way the R-word was used in newspaper headlines, showing no difference between 20th century sports headlines and 19th century news headlines.

"Redskins Start Bloodletting Today," "More Cuts Likely to Follow Full-Scale Redskin Warfare," "Redskins Ambushed," "Redskins Back on the Warpath" and "Giants Massacre Redskins: General Custer Avenged" were sports headlines in the 20th century.

Nineteenth-century news headlines were "Custer's Men Lured Into Trap by Wily Redskins," "On the Warpath ... Redskins Attack," "Redskins Sent to the Happy Hunting Ground" and "Ready for Battle ... The Rebellious Redskins."

Opponents of the majority Native American position say the R-word isn't used against Native people today. They're wrong on this count, too.

Stanford linguist Geoffrey Nunberg, an expert witness in our case, wrote to me on June 13 that "Ron Butters posted a message to the American Dialect Society list a while ago claiming that 'redskin' was rarely used and was not disparaging." Butters is an expert witness for the Washington football club, but did not identify himself as such in his posting.

"I did a search in Google Groups," wrote Nunberg, "and found a number of citations that demonstrate that the word is still widely used in its pejorative sense. I attach these; the names of the relevant discussion groups are in parens. These are all from the last ten years or so:"

— "Hey Redskin: Go back to the Indian Reservation and make some illegal booze." (rec.sport.pro-wrestling)

— "These redskin c***sucks up at the reservation are now claiming that THEY own the portion of Nebraska that pertains to Whiteclay....Times like this make me wish Custer had access to air support and a couple of tactical nukes." (alt.tasteless)

— "Hop down to Any Boat store. Don't you know how to read? I bet your one of the redskin, indian whoop de do's who object to seeing sports teams demeaning native americans and bitch about everything." (alt.scooter)

— "I am getting f***ing tired of these damn redskins belly aching about how the paleface came and stole their land. Why don't they get off their lazy, reservation living-asses and start working?" (alt.discrimination)

— "As I said the white Europeans had 'firesticks' for CENTURIES before the redskin savages even HEARD about them! The redskin savages didn't even have the incredibly complex machine known as 'the wheel' until CENTURIES after other races had it! They were a VERY backwards people!" (alt.atheism)

— "Those indian savages instead opted for much more equisite forms of torture and methods of creating intense pain in their redskin neighbor victims." (Thread, "Indians Are Sleaze Merchants," alt.fan.rush-limbaugh)

— "I stopped into a New York club and found an American Indian bar-tending. I ordered a Manhattan and the redskin f***er charged me twenty-four dollars!" (3do.bad-attitude)

The R-word for public school athletic programs is being challenged legislatively in California and Oklahoma, and both laws deserve to pass. Opponents say the word is an honorific, which is has never been and is not now.

No Native person who has been called the R-word has ever said: "Wow, they must think I'm a football player or a sport mascot or a person covered in red paint for war." It has always been a fighting word and has never been a compliment.

People of ill will and poor taste need to stop playing their dirty word games, and good people must stop enabling them. They must have better things to do with their time than to hang on to racial-based stereotypes and anti-Indian vulgarities.

Suzan Shown Harjo, Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee, is president of the Morning Star Institute in Washington, D.C., and a columnist for Indian Country Today.

*****

What's In A Name?

Prospect: Seriously, 'Washington Redskins' Really Is Racist

Aug. 20, 2006

(The American Prospect) This column was written by Michael Tomasky.

Though a liberal, I am not and never have been a devotee of political

correctness. I think "black" and "Indian" work just fine most of the time and consider "African American" and "Native American" to be superfluous mouthfuls. I think it's more important that disadvantaged schoolchildren memorize their multiplication tables than have their self-esteem preserved.

And I can't quite get behind the idea that people who choose to change their sex should be grouped, rights-securing wise, with people who were born gay.

So I don't usually go in for this sort of thing. But as the new football season approaches, enough is enough: Washington Redskins is a horrendously racist name.

Where do I start? I suppose by saying that this fact should be so obvious to absolutely everyone that the need to change the name at this point, now no longer the "innocent dawn" of the 21st Century, should be beyond debate. I mean … Redskins! Just sit with that word for a while.

These next three paragraphs contain a few offensive words, but using them (or some of them) is the best way to make the point.

Let's start with the mother of all racist pejoratives — you know the word I mean. This one I won't put it in print; it's too lurid. Obviously, no one would name a team the Washington N-----s, and anyway, I don't think Redskins is equivalent to that. We white folk (this includes not just the United States, but pre-U.S. colonialists) may have killed far more native people, but what we did to black people occupies a more prominent place in our national memory, and I think probably rightly so. So the N-word, so fully associated with that history, is a special case, and it has no equal.

But as we know, alas, there are several pejoratives for black people that are one or two ticks down from the big one. And here, we start to see very clear parallels with redskin. The closest one is "spade." Both refer specifically to pigmentation (the latter a metaphor drawn from a deck of cards). Both mock and categorize entire races explicitly because of pigmentation. So if you think Washington Redskins is OK, then you believe that Washington Spades would be fine, too.

And there is more: Because of the nature of the historic conflict between white man and Indian, the word redskin carries another, more implicit meaning — it marks the people described as a different, hence exotic, hence somehow threatening tribe. Here, the equivalency is with Jews. Could we imagine the Washington Hebes?

Obviously, we could not. But Redskin is no better. And an examination of the history of the franchise seals the argument.

The Washington Redskins began life as the Boston Braves. The team played in Braves Field, home of the baseball Boston Braves (later the Milwaukee Braves, today the Atlanta Braves). In 1933, one year after joining the National Football League, the football Braves moved over to Fenway Park. A name change seemed in order. Head Coach William "Lone Star" Dietz was allegedly of part-Sioux descent. Hence, Redskins, in his "honor" (let's consider it a happy accident that Brother Dietz wasn't a quadroon). The team moved to Washington in 1937.

The ignominious roots in the North's most racist city should tell us something. And I just love that notion that the name was meant to honor Dietz. I'm sure it was, but this only reinforces the fact that times and mores change. In 1930s America, it was also an "honor" for Hattie McDaniel to have to act out humiliating mammy stereotypes in order to win her Oscar (after having been pointedly disinvited from Gone With the Wind's world premiere in Atlanta).

But here's what really settles matters for me: The Redskins are historically the most racist franchise in professional football. Indeed, the club integrated only under the direct pressure of the Kennedy administration. The tale goes something like this: The federal government (the Department of the Interior, I believe) built the stadium we now call RFK. Federal law prohibited segregation at such facilities. So if the Redskins wanted to play in the spanking new park, they had to start having black players.

The White Curtain finally fell in 1962, long after most professional football teams. In fact, the NFL integrated in 1946, one year before Jackie Robinson broke baseball's color line (baseball was far more popular in those days, so Robinson was much the bigger deal). Most franchises had several black players on their rosters a decade before Washington did. Again, dwell on this for a moment — nearly every team, for 10 full years; at least a couple thousand games in which the franchise whose name denigrated one race made itself the outlier of its profession by pursuing a policy that denigrated another.

What's this have to do with the name? One might think that possession of the most disgraceful racial record in pro sports history would still weigh, just a bit, on the conscience of the most valuable sports team in North America (yes, more than the New York Yankees, $1.3 billion to $1.03 billion, according to Forbes' 2005 rankings). In a city whose media did a better job of reminding both George W. Bush and Redskins principal owner Daniel Snyder about the burdens of history, this would matter more than it does.

I don't think all Indian names have to go. "Braves" and "Chiefs" are scarcely pejorative terms. Specific tribe names, like the Seminoles used by Florida State, are case by case, and indeed the paladins of FSU have taken care to sit down and talk with present-day Seminoles and work out a rationale for continued use of the name. That's fine. Many colleges, Marquette most especially, have jumped the P.C. shark to extents that can't even be mocked in trying to ditch their anti-indigenous heritages.

But "Redskins" is a very different story. I pray that Suzan Shown Harjo and her comrades who are suing the organization in order to force a name change find justice. Better yet, I pray that Snyder sees reason of his own volition. This is the sort of problem that savvy public relations can easily turn into a virtue. The fans would resist at first, but they could play a role in the renaming, and, as in most things, time would sort the disgruntlement out.

Finally, I pray — and this most fervently — that the team repeats Sunday night's lackluster performance, in which it lost to the Bengals (what Asian cats have to do with Cincinnati I don't know, but at least the only offensive thing about them is their helmets) 19-3, every week until January, or until the franchise wakes up and joins the mid-to-late 20th Century.

Until then, Fail to the Redskins.

Michael Tomasky is the Prospect's editor.

"Redskin" describes "stalwart attributes"?

Someone disagrees with Harjo's "mountain of evidence." From the Washington Post, 1/26/02:

American Indians Among Admirers of Redskins Name

By Marc Fisher

Scalp 'em, swamp 'em

We will take 'em big score

Read 'em, weep 'em, touchdown

We want heap more

"Hail to the Redskins," original 1937 lyric

In a few days, football will fade from view and the Redskins will lurk in the background as an autumnal hope. But the debate over the Redskins' name knows no seasons; it has been with us for more than four decades and shows no sign of abating.

With local governments now in the act, urging Dan Snyder to pull an Abe Pollin and change his team's name to something bland, the name game takes on a new urgency.

The name changers appear to have the upper hand, as they sweep the nation forcing high schools and colleges to abandon traditional mascots and scrap names such as Indians, Chiefs, Braves and Warriors.

Interestingly, most of the people who sizzle with outrage over Indian team names and mascots are not Indians. American Indians can be found vigorously arguing on both sides. Academics are split, too: Anthropologists call team names and mascots humiliating, while linguists say "redskin" describes "stalwart attributes." Even dictionaries disagree (the Oxford English says "redskin" is "generally benign," while Webster's says it is "usually offensive").

The Redskins debate — in addition to the latest condemnation from the Metropolitan Council of Governments, a challenge to the team's trademark is tied up in federal court — focuses on the genesis of the name (was it born as an ethnic slur?) and its use today (does it denigrate Indians?).

There are at least three versions of the name's origin. The official story, says team spokesman Karl Swanson, is that when the Boston Braves football team left Braves Field to play at Fenway Park in 1933, owner George Preston Marshall needed a new name for his squad.

He chose Redskins in honor of Lone Star Dietz, the team's coach and an Indian who often wore an eagle feather headdress, beaded deerskin jacket and buckskin moccasins. Dietz brought four to six — accounts vary — Indian players with him to Boston from the Haskell Indian School in Kansas, where he had coached for four years.

Another version has the team being named for the white men who dressed up as Indians to stage the Boston Tea Party at the start of the American Revolution. Yet another genesis story says the name stems from the colored clay that Plains Indians used to paint themselves for tribal ceremonies.

Whichever version is right, "the reality is more benign than people on both sides of the fence are attributing to it," says sports historian and museum consultant Frank Ceresi. "The name was meant very, very positively."

The genesis may always remain murky because Marshall never wrote a word about his choice, the Boston newspapers from the time are silent on the question (football was a minor sideshow in those days), and survivors of the period offer conflicting and vague recollections. But it is clear that the Boston Redskins, who moved to Washington in 1937, sought to capitalize on their Indian players and coach: The team played wearing red war paint. And Indian players from the time considered the name and trappings an honor.

So does Walter Wetzel, former chairman of the Blackfoot tribe and president of the National Congress of American Indians in the 1960s. By the early '60s, the Redskins had dropped any reference to Indians in their logo, uniforms and merchandise. Wetzel went to the Redskins office with photos of Indians in full headdress.

"I said, 'I'd like to see an Indian on your helmets,' " which then sported a big "R" as the team logo, remembers Wetzel, now 86 and retired in Montana. Within weeks, the Redskins had a new logo, a composite Indian taken from the features in Wetzel's pictures. "It made us all so proud to have an Indian on a big-time team. . . . It's only a small group of radicals who oppose those names. Indians are proud of Indians."

Snyder, meanwhile, intends to keep the name, no matter the protests. "Frankly, we don't hear much from fans about this," Swanson says. "Words take power from their usage. We don't use funny mascots. We don't have tomahawk chops. We've always used the word in a respectful way, to mean tradition, courage and respect."

© 2002 The Washington Post Company

Rob's reply (1/28/02)

A few comments on your "redskins" article:

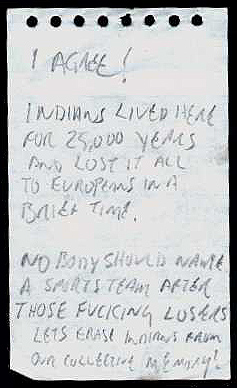

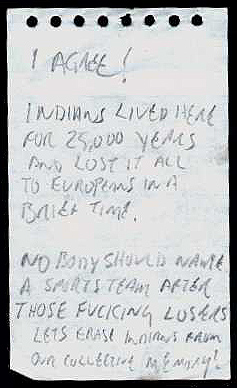

When you say, "Interestingly, most of the people who sizzle with outrage over Indian team names and mascots are not Indians"—well, of course, since about 99% of Americans aren't Indians. The more important question is what percent of Indians and non-Indians oppose "redskins." From what I've seen, the percent of Indians who oppose this word may approach 80%.

When you say, "Another version has the team being named for the white men who dressed up as Indians to stage the Boston Tea Party at the start of the American Revolution. Yet another genesis story says the name stems from the colored clay that Plains Indians used to paint themselves for tribal ceremonies," you've confused two things. One is how the Washington team chose the term "redskins" for its name. That may include the Lone Star Dietz and Boston Tea Party theories. Another is where the term "redskins" originally came from. That includes the "red clay" theory and a leading theory you didn't mention: that "redskins" came from the European practice of collecting bloody Indian scalps for bounties.

Quoting Wetzel without quoting an Indian who disagrees with him is bad journalistic practice, unfortunately. Any search would identify thousands of Native people who would tell you Wetzel doesn't know what he's talking about. I hope you'll consult with one of them next time you write about the subject.

Rob Schmidt (WASP)

Publisher

PEACE PARTY

*****

Addendum (7/15/02)

I've never heard any linguist say "redskin" describes stalwart attributes. Naturally, Fisher doesn't name these linguists so we can examine this claim for ourselves.

Which attribute is supposed to be "stalwart," anyway? Is it the redness or the skin? Any other attribute is in the unnamed linguists' minds, not in the word itself.

Also, Fisher is dissembling by saying the dictionary listings range from "generally benign" to "usually offensive." I checked three dictionaries online and you can see what I found (above). It would be more accurate to say the dictionary listings range from "generally benign" (rare) to "usually offensive" (common) to "taboo." In other words, the preponderance of dictionaries suggests "redskins" is offensive.

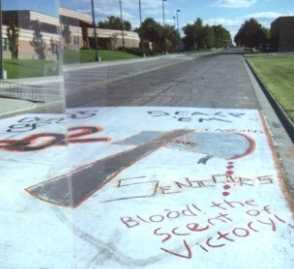

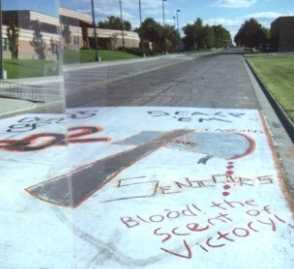

Incidentally, the lovely "Authentic Spear Throwback Helmet" (pictured above) is available on the Washington Redskins website—only $289.99. Good thing we know this helmet doesn't imply Indians were savage spearchuckers.

Another reply to Fisher

Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments rebuts Fisher's claim

Marc Fisher replies to Rob (1/31/02)

Thanks for your note. I write a column that appears in the Post three times a week; in it, I present my take on the news. It is a reported column and I eschew punditry, but it remains a column, not a news story, and therefore I do not always present all sides of an issue, but rather my own view of it. While I spoke to many people—Indians and non—who oppose the Redskins name, and I have quoted them at length in previous columns on the same issue, I did not do so in this most recent column because those viewpoints are rather thoroughly discredited. For example, there is no evidence backing up the claim that the name stems from the scalping of Indians. All six of the academics I consulted with said they have been unable to find any evidence to back that notion. I'm interested in your statement that 80 percent of Indians oppose the name; most of the Indians I've heard from endorse it. That's hardly a scientific sampling, but I wonder if you know of any effort to do a more thorough survey of Indian opinion on this. Thanks again for reading the column and passing along your comments.

Best,

Marc Fisher

The Washington Post

Rob's reply (1/31/02)

>> It is a reported column and I eschew punditry, but it remains a column, not a news story, and therefore I do not always present all sides of an issue, but rather my own view of it. <<

Even in news analyses and columns, presenting both sides of an issue is the ideal. But if you've written on the subject before and presented the other side, I understand.

>> While I spoke to many people—Indians and non—who oppose the Redskins name, and I have quoted them at length in previous columns on the same issue, I did not do so in this most recent column because those viewpoints are rather thoroughly discredited. <<

I said you confused the origin of the word with the origin of the Redskins team name. Whether you include the "bloody scalp" theory or not, that point remains valid.

I'm not an expert on the origins of the word "redskins," but six people who say they can't prove the "bloody scalp" theory doesn't discredit it. It merely means the origin remains to be determined. How many experts have traced the word to the "red clay" origin and what's their evidence? Until you can answer that, I'd say you haven't credited or discredited either theory and should present both, along with any others that may apply.

>> I'm interested in your statement that 80 percent of Indians oppose the name; most of the Indians I've heard from endorse it. That's hardly a scientific sampling <<

Definitely not. First, the people who call or write you are likely to be those who favor your position. Second, you can't even verify that a caller or writer is an Indian without a lot of work. Third, you write for a paper that supports the Washington Redskins. Thousands, perhaps millions, of fans in your area are biased in favor of the team.

>> I wonder if you know of any effort to do a more thorough survey of Indian opinion on this. <<

My figure comes from the Indian Country Today newspaper, 8/7/01. The paper polled Indian "opinion leaders" and 81% of the respondents found the term "redskins" offensive. While that sample is unrepresentative also, I'd say it's far more representative than people who contact newspaper columnists in the Washington Redskins area.

I cite the figure because it mirrors what I see in the media—not in the self-selected pool of people I talk to. Hundreds of Native tribes and organizations, each with hundreds or thousands of members, have gone on record opposing mascots. So has every well-known Indian I've heard about—people like Russell Means and Sherman Alexie. If any Native leader has come out in favor of mascots, I missed it.

In the collective reading I've done on the subject—many hundreds of articles—I'd say the vast majority of Native people (not liberal white agitators) oppose Indian names and mascots such as "Redskins." I'd say the 80% figure reflects the reality. Until I find better information, I'm comfortable using that as the "best guess."

Rob Schmidt

Publisher

PEACE PARTY

P.S. I'll let some Native colleagues know you've heard mainly from mascot supporters. They may help redress the imbalance.

*****

The bloody-scalp theory (7/16/02)

The following is an excerpt from an article published c. 5/29/02. The article is about activist Eugene Herrod's battle against the state of California for issuing a "REDSKINS" license plate. It's noteworthy here because Herrod describes the research of Duane Champagne, a respected Native scholar and author.

Champagne has published research showing the word's derivation from the practice of collecting scalps. He's put his name on the research, unlike the anonymous scholars Fisher mentioned. If Fisher thinks someone or something has discredited this work, let him identify the source. Until then, Champagne's work is as definitive as anything we have.

For Indian activist, it's matter of respect

By Anita Stackhouse-Hite, The Porterville Recorder

Eugene Herrod is a full-blooded Muscogee Creek Indian from New Orleans. He is also a political activist, responsible for taking the Department of Motor Vehicles to task for allowing the use of the word "redskin" and Indian images on personalized license plates in California.

"I filed a complaint against the DMV in October of 1999 charging they were in violation of the state vehicle code," Herrod said. "State code says personalized plates cannot be obscene or racially offense. In 1999, I saw personalized plates with the word 'redskin' on them. I supplied them with documentation, and they recalled all such plates, including those with the words 'kike' and 'Jap.' "

Herrod particularly takes issue with the use of the word "redskin" because of its origin. Duane Champagne, director of Indian studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, studied the etymology of the word and published a report.

According to Herrod, who is "50ish," Champagne's report shows the word "redskin" was coined in the 1800s when the British Crown put a bounty on the capture of Indians. Bounty hunters couldn't be paid without turning in skin of murdered Indians.

"The bounty called for their scalps, or the skin from their fingers or anywhere else," Herrod said. "This skin was called redskin, because it was the bloody underside of the skin. There is no honor in that name, no matter how it may have evolved to in the minds of people today."

Comment: That should be the 1600s, not the 1800s, of course. The British crown didn't rule America in the 1800s.

As for Indians who are proud to see themselves slurred by nicknames such as "redskins," see Team Names and Mascots for some interesting research on the subject. I suspect the reasoning is similar to the reasoning of African Americans who have adopted "niggers" as a term of pride. It doesn't change the word's offensive history.

Native people sometimes use the slang term "skins" for themselves. Clearly, they've appropriated "redskins" and transformed it into a positive symbol. As with black people, the key is who gets to label whom. Many ethnic groups joke about their own ethnic foibles, but don't appreciate it when outsiders make the same comments.

Another note to Fisher (1/31/02)

I've read (in Through Indian Eyes) that the word came from the Delaware practice of painting one's face red with berry juice—not from smearing red clay from out West on the face. So there's a third theory for you to mention. Since the word arose shortly after the first European contacts, it seems plausible.

But the origin of the word isn't particularly relevant to the question of whether it's offensive or not. It's offensive because it stereotypes Indians: they don't have red skin, and they don't wear berry juice or clay on their faces. More important, it's offensive because the vast majority of Natives think it's offensive. You can rationalize almost any ethnic slur, but that doesn't change people's feelings about it.

Rob Schmidt

Publisher

PEACE PARTY

More on the origin of "redskins"

Indians really red-skinned?

Harjo: Paper Beats Rock and the Spoken Word

A Linguist's Alternative History of 'Redskin': Term Did Not Begin as Insult, Smithsonian Scholar Says; Activist Not So Sure

Someone else responds to Fisher (1/31/02)

A reply to a request I sent out on the Internet titled "Columnist thinks most Indians favor 'Redskins'—needs help":

Dear Robert,

The controversy around this name is well known. Whatever the origin, [it] seems irrelevant. It is patently offensive to a large number of people—period. Therefore, the name should be changed, regardless of numbers, statistics, etc. For example, we would not consider naming a team, "The New York Kikes" regardless of how many people liked the name or the origin of the term "kike." Any discussion other than how fast the name should be dropped would be an outrage. Imagine someone asking the Jewish people to prove the offensiveness and to do the research to justify their offense! Why are Native people not afforded such consideration? Perhaps that is the more relevant question.

Sincerely,

Rhonda Cervantes

Rob replies to Fisher once more (2/5/02)

The following article rebuts some of Fisher's claims. An excerpt shows how he shaded the truth by invoking Dietz and Wetzel:

Washington Chief-Making and the R-Word

Posted: February 04, 2002 -- 3:00pm EST

by: Suzan Shown Harjo / Columnist / Indian Country Today

Snyder's lawyers were dispatched to Indian country to find relatives of Lone Star Dietz, the team's long ago assistant coach. Team mythology has it that George Preston Marshall (the team's owner who was infamous for his racism) named the team after Dietz.

In 1933, whenever newspapers or movies wanted to use the worst slur for Indians, they used the R-word, so that must have been some kind of honor.

Dietz had a Sioux mother, but was raised by his German father's family, far to the east of Sioux country. His first contact with Indians was in his late teens at the federal boarding school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where the motto was "Kill the Indian, Save the Man."

Wetzel, a Blackfeet senior, was identified in the column as an NCAI president in the 1960s, conveying the misimpression that NCAI supported the team's name then or now.

One of the Native people who brought our lawsuit was executive director of NCAI in the 1960s, Vine Deloria, Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux), who is a lawyer, a retired college professor and author of two dozen books. I was NCAI's executive director in the 1980s. NCAI officials testified in the 1990s that the organization opposed the team's name in the 1960s and thereafter.

The column did not identify Wetzel as part of "Republican Indians for Nixon" or as brother-in-law to CIA operative, White House plumber and convicted Watergate felon Howard Hunt. Now, that's the interesting story, but not the one that serves the Washington chief-makers.

As I wrote to Fisher:

Note the mention of the "voluminous evidence about the meaning and use of the R-word and how most Native Americans despise it." This evidence convinced three judges to unanimously rule the name "Redskins" was offensive and therefore not protected by patent and trademark law.

Unless you've reviewed this voluminous evidence and can rebut it, I'd say it stands as the definitive word on how most Native Americans feel about "Redskins." Without further input, I'll go with the judges who have reviewed the voluminous evidence over a columnist who hasn't.

Rob

More thoughts on Native use of "redskins"

From the Washington Post, 9/16/02:

Name of the Game for Redskins Is 'Intolerance'

Talking with some of the hundreds of Native Americans who gathered on the Mall for a national powwow this weekend, none felt the name was complimentary. One teenager from the Crow tribe did say that he was not fazed one way or the other and noted that "on some reservations, you can see people wearing Redskins caps. It's their way of identifying with the urban scene."

And I can go into any slum where blacks are confined and hear them calling one another "nigger," too. The extent to which members of both groups adopt as their own the words and symbols of oppression are manifestations of mental illness, as I see it—not a compliment at all.

"Redskins" in the Stereotype of the Month contest

Sports DJ on NCAA: "Paleface know what best for redskin?"

Anti-Redskins movement is "ultra-liberal initiative full of PC"

Redskins "Piss on Dallas" decal features big-nosed Indian

"Rational thought disappears" with Calif. "Redskins" bill

Tulsa-area high school hosts "Redskins for Christ" website

Head: "Cowboys scalp 'Skins to maintain NFC East lead"

Fein: Activists = "spoiled children of political correctness"

Headline: "Cowboys Skin Redskins for Thanksgiving"

LA Times columnist says "Redskin" slur is unimportant

Minn. editorialist thinks "red skin" is onion or girl's blush

Kan. football news: "Redskins buried at Burial Grounds"

The Redskin magazine controversy

Mohawk slams Redskin "rubbish"

"Redskins" all over the continent?

Survey on Redskin magazine

Wassegijig and Yeagley discuss Redskin

Redskin writer ducks challenge

Comparing Native sex mags

Kristallnacht game and Redskin magazine

Another issue of Red Ink

Natives denounce Redskin

Educating Russ about Redskin

Challenge for Redskin writer

Magazine controversy continues

Response from Redskin model

Team RSM defends Redskin magazine

Reactions to Redskin magazine

Letter to Redskin magazine

"Redskin" magazine to launch

More on "redskins"

Chinks, Sambos, and Redskins

"Redskins" are animals

Redskins, Brownskins, or Blackskins

Colusa drops "Redskin"

The professor and the Redskins

Educating readers about "redskins"

Attacking Imus while watching Redskins

R-word = n-word

Indian watches Redskins

Related links

Team names and mascots

Smashing people: the "honor" of being an athlete

The Sports Illustrated poll on mascots

The harm of Native stereotyping: facts and evidence

Readers respond

"[A] parable about a football game between the Whiteys and the Darkies" is "based on a fallacy."

"Should team mascot names be reported in sports sections? Or does censoring them...have some sort of positive effect on the situation...?"

"I thought you might be interested in an example where a Native American baseball team apparently named itself the 'Red Skins.'"

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.