Raymond William Stedman offers a good review of this subject in his book Shadows of the Indian. In a chapter titled "La Belle Sauvage," he begins with Sacheen Littlefeather's infamous appearance at the Academy Awards in place of Marlon Brando:

Raymond William Stedman offers a good review of this subject in his book Shadows of the Indian. In a chapter titled "La Belle Sauvage," he begins with Sacheen Littlefeather's infamous appearance at the Academy Awards in place of Marlon Brando:

Raymond William Stedman offers a good review of this subject in his book Shadows of the Indian. In a chapter titled "La Belle Sauvage," he begins with Sacheen Littlefeather's infamous appearance at the Academy Awards in place of Marlon Brando:

Raymond William Stedman offers a good review of this subject in his book Shadows of the Indian. In a chapter titled "La Belle Sauvage," he begins with Sacheen Littlefeather's infamous appearance at the Academy Awards in place of Marlon Brando:

...[C]olumnist Harriet Van Horne was obviously captivated by the "gentle-voiced Apache maiden...who appeared on the stage in tribal dress." Once the furor was over, suggested Van Horne, "people will still remember that lovely Littlefeather, in her shining braids, explaining as best she could why the most honored actor of the year was letting the chalice pass." The columnist's "heart went out to that Apache lass in her long braids." And that, she asserted, was "precisely what Marlon Brando had in mind.

Was that what Brando had in mind? If so, he had selected his propaganda device shrewdly, for it was, simply, that of the lovely and selfless Indian princess, possibly the most enduring image this land has known. Brando's braided messenger was Pocahontas and U-le-lah and Minnehaha and Redwing and Sacagawea and Sonseeahray and Summer-Fall-Winter-Spring and, some would say, the allegorical America. She was the female manifestation of the Noble Savage myth, changed little from the image created centuries earlier, and far more endearing and viable in the twentieth century than her male counterpart, the forest nobleman.

Stedman describes the self-effacing and self-sacrificing Pocahontas as the model of La Belle Sauvage, then details the image's history:

Through the nation's growing years Pocahontas the Nonpareil—intelligent, guileless, lovely, courageous—turned into Pocahontas the Imitated. Not a season went by that some author, or artist, or playwright, or trademark maker did not call upon her image.

Guy-Kirby Letts continues the thread in his essay on the "Indian Princesses and Cowgirls: Stereotypes from the Frontier" exhibit:

As representations changed, the images of First Nations women as Indian princesses who embodied mystery and exoticism began to emerge. During the post World War I era, the Indian princess is repeatedly portrayed alone in the pristine wilderness, scantily clad in a buckskin or tunic dress, sporting a jaunty feather over two long braids. Most striking, however, is that all of the models are notably white-skinned women.

In What's the Real Story on Sacagawea? the Straight Dope lays the problem, er, bare:

[T]he Shoshone (like other North American Indians) had no concept of royalty, as Lewis's journals make clear. The "Indian princess" stereotype turns up a lot in misleading history, and even more in third-rate television and movie westerns. The stock Indian princess saves the white hero from her less enlightened brethren, and is often depicted as being tall, beautiful, and freakishly light-skinned. Think of Sacagawea as portrayed in the 1955 film The Far Horizons by that great Native American actress, Donna Reed.

Stedman quotes a description from the 1963 novel The Gates of the Mountains that fits many of the Indian "princesses." Note how the woman must look and act Caucasian to be palatable to the intended audience. By definition, beauty is in the eye of the white, majority beholder.

Stedman quotes a description from the 1963 novel The Gates of the Mountains that fits many of the Indian "princesses." Note how the woman must look and act Caucasian to be palatable to the intended audience. By definition, beauty is in the eye of the white, majority beholder.

Sacajawea was not shy, but appealing soft of speech and manner. And she was gracefully feminine beyond any woman I had seen....Her head was not elongated, as so many of the Indians, but rather small and round, Caucasian in shape. So, too, were her features Caucasian.

Sacajawea was not only an uncommonly pretty young girl, she was a regal woman by any standard of any race. No man who ever knew her, was quite the same again.

Grace was hers, and good manners. Intelligence she had, and a quick and lively tongue. Dignity covered her every move. She could look like a queen while gutting an elk....She had no crown but her auburn hair....But Sacajawea was a ruler of men's hearts by God's will.

In short, Pocahontas and company were the female equivalent of the male Indian helpmates: Man Friday, Chingachgook, Tonto. James W. Loewen discusses the role of these "good Indians" in his book Lies Across America.

Sex under the buckskins

One element Stedman doesn't address is La Belle Sauvage's sexual overtones. Western men have always thought of "foreign" or "exotic" women as delectable forbidden fruit. Whether it was nubile black slaves, fiery Latina peasants, or demure Asian geishas, they presumed the servile facade hid a siren of smoldering sexuality.

As Stedman's "ruler of men's hearts" example shows, the Indian princess was little different. Other examples reinforce the point. Malinche, the slave girl who translated the Aztec language for Cortés, became his mistress and bore him a son. In Dances with Wolves, Kevin Costner makes a beeline for the comely Indian maiden, who turns out to be a captured white woman. People (including Disney's filmmakers) want to believe Pocahontas had blissful romances with John Smith and John Rolfe.

As in the rest of our culture, we've made the iconic Indian princess more overtly sexual in recent years. She's still with us in old Cher videos, movies like Road to El Dorado, and comics like GEN13. And each time she reappears—for instance, in the OutKast outrage—people are likely to protest.

Perhaps because of this, you don't see the image much in the mainstream media anymore. But the more innocent version is still on display. Oddly, you can find it often in mass-market dolls, plates, and other alleged collectors' items. Tourist shops in Indian Country and at kitschy places like Disneyland also carry the retrograde icons.

If you can't have one, be one

What about non-Indians who claim to be descended from Indian princesses? In an excerpt from Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, Vine Deloria Jr. explains the phenomenon:

During my three years as Executive Director of the National Congress of American Indians it was a rare day when some white didn't visit my office and proudly proclaim that he or she was of Indian descent.

Cherokee was the most popular tribe of their choice and many people placed the Cherokees anywhere from Maine to Washington State. Mohawk, Sioux, and Chippewa were next in popularity. Occasionally, I would be told about some mythical tribe from lower Pennsylvania, Virginia, or Massachusetts which had spawned the white standing before me.

At times I became quite defensive about being a Sioux when these white people had a pedigree that was so much more respectable than mine. But eventually I came to understand their need to identify as partially Indian and did not resent them. I would confirm their wildest stories about their Indian ancestry and would add a few tales of my own hoping that they would be able to accept themselves someday and leave us alone.

Whites claiming Indian blood generally tend to reinforce mythical beliefs about Indians. All but one person I met who claimed Indian blood claimed it on their grandmother's side. I once did a projection backward and discovered that evidently most tribes were entirely female for the first three hundred years of white occupation. No one, it seemed, wanted to claim a male Indian as a forebear.

It doesn't take much insight into racial attitudes to understand the real meaning of the Indian grandmother complex that plagues certain whites. A male ancestor has too much of the aura of the savage warrior, the unknown primitive, the instinctive animal, to make him a respectable member of the family tree. But a young Indian princess? Ah, there was royalty for the taking. Somehow the white was linked with a noble house of gentility and culture if his grandmother was an Indian princess who ran away with an intrepid pioneer. And royalty has always been an unconscious but all-consuming goal of the European immigrant.

The early colonists, accustomed to life under benevolent despots, projected their understanding of the European political structure onto the Indian tribe in trying to explain its political and social structure. European royal houses were closed to ex-convicts and indentured servants, so the colonists made all Indian maidens princesses, then proceeded to climb a social ladder of their own creation. Within the next generation, if the trend continues, a large portion of the American population will eventually be related to Powhattan.

While a real Indian grandmother is probably the nicest thing that could happen to a child, why is a remote Indian princess grandmother so necessary for many whites? Is it because they are afraid of being classed as foreigners? Do they need some blood tie with the frontier and its dangers in order to experience what it means to be an American? Or is it an attempt to avoid facing the guilt they bear for the treatment of the Indian?

Indian princesses in the Stereotype of the Month contest

Indian princesses on Facebook

"All Native women are hoes"

Nude Navajo model

Indian maiden in PISTOLFIST

A look at LIVING CORPSE #3

Pageant contestant = sexy chief

Aztecs game cover shows scantily-clad woman wielding axes

Indian women are "squaws," sex objects in YouTube videos

eBay auctions Red Indian girl, squaw, Pocahontas costumes

Indian Restaurant waitresses dress like sexy Indian maidens

OMEGA FLIGHT: Sexy young woman becomes a shaman

OUTLAW SQUAW stars generic buxom Indian beauty

"Butterfly dancer" ornaments portray Indians as fairies

Card shows chief admiring Little Miss Sunbeam as Indian

Mattel debuts slender "Princess of the Navajo" Barbie doll

Disney Store sells Pocahontas costume with wig and fringe

Miss USA dresses as scantily-clad chief in faux warbonnet

More examples of Indian princesses

Dawnstar from the Legion of Super-Heroes

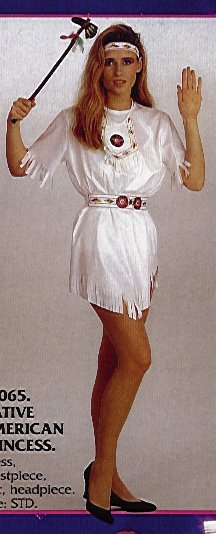

Sexy Indian Halloween costume from an eBay auction

Sexy Indian Halloween costume from an eBay auction

Sexy Indian Halloween costume from an eBay auction

Enola the shaman (Elena Finney) from Charmed

Faux Indian maidens on OutKast's Grammy performance

Faux Indian maidens on OutKast's Grammy performance

Indian babe with wolf from WILDE KNIGHT

Janet Pete (Alex Rice) in Coyote Waits

Indian Girl from 3 Wishes Lingerie

Sexy Indian from 3 Wishes Lingerie

Pocahontas from 3 Wishes Lingerie

Suede and Feathers from 3 Wishes Lingerie

Sexy Chief from 3 Wishes Lingerie

Naughty Navajo from 3 Wishes Lingerie

Alope (Anita Brown) from The Lone Ranger

Warrior Nations Amazons

Kyla (Tamara Feldman) on Smallville

Janet Pete (Alex Rice) in Skinwalkers

The First American Dinner Party

Ice skater Krylova dances "Last of the Mohicans"

Spirit of the Earth Barbie Doll

Taran from PETER PARKER: SPIDER-MAN 2001

Gen13's Rainmaker (another view)

Woman playing Tiger Lily in Peter Pan

"River of Dreams" painting

Loving Heart doll

Morning Bird doll

Native American princess costume

TOMAHAWK #137

Land O' Lakes butter maiden

Topless Indian maiden—probably from a WW II warplane

Fruit Gum ad

More on Indian princesses and sex objects

Nude Navajo model

Criticism of "Savage Love"

Monkman's central figure

The Redskin magazine controversy

Land O' Lakes poem

Masturbatory fantasies

The first Indian princess?

The Rez Dog calendar: role models or sex objects?

Tiger Lily in Peter Pan: an allegory of Anglo-Indian relations

Pocahontas bastardizes real people

Pocahontas II: flawed again

The facts on Sacagawea

Related links

Tonto and the "good Indian"

"Marriage or bust" for Disney's women

Squelching the s-word

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.