Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

The Political in Literature

(10/4/00)

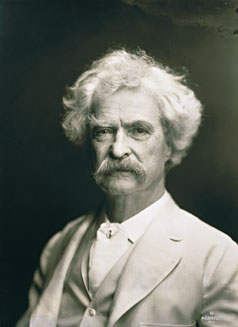

[Shelly] said that "poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world." I would say intellectuals are in general the unacknowledged legislators.

Norman Podhoretz

Long ago — it was the 18th century — a great and eccentric defender of literature — it was Doctor Johnson — wrote, in the preface to his Dictionary: "The chief glory of every people arises from its authors."

Susan Sontag, "The Truth of Fiction Evokes Our Common Humanity," LA Times, 4/25/04

*****

Politics makes good literature

The entire edition of the 8/13/00 LA Times Book Review is devoted to "Politics and the Novel." Here are what some famous writers had to say on the subject:

Virtually every ambitious novel is at least implicitly political, and most are explicitly so. Novels create sympathies, arouse indignations, nourish understanding. They instruct us not to be reductive.

Susan Sontag

Since I believe all novels are political, I certainly believe that it is possible for a novelist to admix deliberate political purpose and aesthetics....

Rick Moody (The Ice Storm)

There is no inevitable contradiction between the "political" and the "aesthetic."

Joyce Carol Oates

I can't see any reason other than complacency and lack of talent that would prevent a 21st century writer from writing fiction that is both aesthetically adventurous and politically powerful.

Nadine Gordimer

I am convinced that it is possible today, as it was in the past, for a great writer to write a great novel with a deliberately political purpose, but the purpose has to inhere in the subject matter.

Louis Begley (Wartime Lies)

I don't set out to write a political novel, but if the political subject suits the story, I don't hesitate to be political.

John Irving

...[E]very novel where American outcasts explore frontiers of truth, beauty and freedom outside the rule of class, custom and social uplift, is a political novel, from "Moby Dick" to "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest."

Jeremy Larner (screenwriter, The Candidate)

Had I the time, I'd put forth the argument that all novels are political....Today, I am a believer in the contemporary novelist's ability to embrace and sustain political purposes. Plus, I believe it's possible to do so while adhering to high aesthetic and artistic criteria.

Wanda Coleman

Obviously, American politics today remains as worthy a subject for a novelist as any other human activity....I have to believe that a great literary artist still could find a way to make even our present dismal political scene seem worthy of passionate exploration.

Pete Hamill

More from Susan Sontag's essay, "The Truth of Fiction Evokes Our Common Humanity," in the LA Times, 4/25/04:

Literature is a form of responsibility — to literature itself and to society. By literature, I mean literature in the normative sense, the sense in which literature incarnates and defends high standards. By society, I mean society in the normative sense too, which suggests that a great writer of fiction, by writing truthfully about the society in which she or he lives, cannot help but evoke (if only by their absence) the better standards of justice and of truthfulness which we have the right (some would say the duty) to militate for in the necessarily imperfect societies in which we live.

Obviously, I think of the writer of novels and stories and plays as a moral agent. In my view, a fiction writer whose adherence is to literature is, necessarily, someone who thinks about moral problems: about what is just and unjust, what is better or worse, what is repulsive and admirable, what is lamentable and what inspires joy and approbation. This doesn't entail moralizing in any direct or crude sense.

Serious fiction writers think about moral problems practically. They tell stories. They narrate. They evoke our common humanity in narratives with which we can identify, even though the lives may be remote from our own. They stimulate our imagination. The stories they tell enlarge and complicate — and, therefore, improve — our sympathies. They educate our capacity for moral judgment.

From an essay in The Nation, 9/17/01, titled "The Public Role of Writers and Intellectuals":

Yet at the dawn of the twenty-first century the writer has taken on more and more of the intellectual's adversarial attributes in such activities as speaking the truth to power, being a witness to persecution and suffering, and supplying a dissenting voice in conflicts with authority.

Edward Said

For more on what leading writers have to say on the subject, plus a list of hundreds of politically-oriented novels (Doctor Zhivago, Johnny Got His Gun, Animal Farm, Black Boy, Slaugterhouse-Five, Uncle Tom's Cabin, The Grapes of Wrath, Andersonville, The Sound and the Fury, A Farewell to Arms, Crime and Punishment, and many more), check out this Book Review at your local library.

Many genre works also contain political messages, either overt or covert. The most obvious cases include spy and techno-thrillers, legal dramas, mysteries and police procedurals. Other genres send political messages by saying nothing, not asking questions, and supporting the status quo. For instance, the typical Western upholds the tenets of Manifest Destiny, while the typical romance touts the importance of wealth and status.

The same also applies to comic books and comic strips—really, to any genre of art or literature. For a discussion of politics in comics, see Indian Comics: Art vs. Propaganda.

Politics makes good poetry, too

Part of an essay on incorporating politics into poetry—and by extension, into other forms of writing and art:

Lyle Daggett

Political Poetry

"Political" poetry. All human activity is political because it takes place in a context—the context of history. Sending someone a recipe for crab meat salad is one thing if you work food prep in a restaurant kitchen. It means something else if you're Nancy Reagan.

Poets have been political, in some sense of the word, from the earliest beginnings to the present. Enheduanna, Sumerian poet, priestess of the moon goddess Inanna, the earliest poet whose name is known. The Chinese government compiled collections of popular folk songs—for example, the Shih Ching, the Book of Songs—as a way of learning something about what the people were thinking. (Did Nixon listen to Bob Dylan or Joan Baez or Pete Seeger? Does George Bush listen to Billy Bragg or Tracy Chapman or rap music?)

Homer was political. (George Bush on the walls of Troy.) The Bhagavad Gita (which J. Robert Oppenheimer quoted as he watched the first atomic bomb explode in the New Mexico desert) was and is political. The plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles and Euripedes were defining forces in Greek society. Dante and Shakespeare and Milton were all political. (If Dante were writing today, who would he consign to the ninth circle of Hell?) The great flowering of art and culture in medieval Spain grew originally from the founding of a new Umayyad dynasty in exile by survivors of the conquest of Damascus by the Abbasids. The trouveres and troubadours of medieval France lived in a time of constant upheaval and displacement and continuously shifting political alliances, in which most if not all of them were intimately involved. (Many died during the wholesale slaughter that took place during the Albigensian crusades, following which troubadour poetry essentially came to a halt.)

Chaucer was political, Tu Fu was political, Murasaki Shikibu was political. Andrew Marvell, William Blake, Shelley, Keats, Byron, Whitman, Rubén Darío, José Martí, Yosano Akiko. Political, in at least some sense of the word.

What we're talking about here is something more specific. We're talking about poetry that expresses or reflects—either explicitly or at least by suggestion—politics that are left-wing, working-class, populist, or of a similar character.

How to combine politics with creative work remains an unsettled question on the political Left. This is not simply a question of Socialist or Communist Realism versus whatever else.

The widespread stereotype of Socialist Realism emphasizes the huge public portraits and statues of Lenin, Stalin, Mao, etc., and maybe allows for some murals and poster art of muscle-bound workers in factories and rosy-cheeked starry-eyed young men and women gazing off at the bright horizon of the future. This, again, is the stereotype.

But it should be patently obvious that public portraits and monument sculpture, poster art, industrial murals and calendar art, and so on, comprise only a portion (and not necessarily the best) of a culture's art. We cannot judge the effectiveness of Socialist Realism (or any other artistic movement or tendency of the political Left) based only on the more mediocre or homogenized examples.

Should we judge the art of capitalist societies based solely on Norman Rockwell and Mount Rushmore? Should we judge American literature based on McGuffey's reader? Are these the basis for the prevailing critical standards advocated by the literature and art departments at leading universities?

For every Norman Rockwell there's a Diego Rivera, a David Siqueiros, a Walter Crane, a Sue Coe; for every Edgar Guest and Joyce Kilmer there's a Thomas McGrath, a Muriel Rukeyser, a Hugh MacDiarmid.

Politics makes good movies, too

A screenwriter named Douglas MacKinnon wrote a diatribe about the liberal "bias" in movies and said his goal was to write a script free of politics. Other writers quickly took him to task. From the LA Times, 8/21/04:

LETTERS

Life and art are political

Douglas MacKinnon's Counterpunch article ["Insert Bias in Films — Deduct From the Bottom Line," Aug. 16] detailed his self-described "Republican" take as to how, if someone was to buy one of his screenplays, he "would do everything" in his power "to ensure that it contains no political viewpoint" and that if moviemakers "want to get into politics, then they can run for office, take out ads or make documentaries." May I humbly submit this is a lousy way to approach a career in movies, literature or art of any kind?

Under this rubric, MacKinnon would have been unable or unwilling to contribute to the scripts of films as diverse as "Dr. Strangelove," "Network," "To Be or Not To Be," "Confessions of a Nazi Spy," "Coming Home," "Apocalypse Now," "The Green Berets," "Full Metal Jacket," "Fail-Safe," "Spartacus," "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington," "Meet John Doe," "I Was a Communist for the FBI," "The Parallax View," "The Great Dictator," "All the King's Men," "A Face in the Crowd," "The Best Man," "The Last Hurrah," "The Alamo," "Seven Days in May" etc., not including decades of classic European films, which have always embraced agitprop.

All movies are political, either overtly or coded, often unwittingly. Life is political. To pretend otherwise is to kid yourself and your audience. The idea of abrogating your point of view as an author because it might "potentially drive down the box-office for your film" seems to me a recipe for Instant Bad Art.

Of which we have enough already, don't you think?

Joe Dante

Los Angeles

Let MacKinnon neuter his "product," as he denotes his work, if that is his inclination. The void at the center of the work without viewpoint speaks volumes about the soul of the writer ... or, should I say, the maker of the product.

Richard P. McDonough

Irvine

For some discussion of the political in television, see Globalization According to Gilligan.

More relevant quotes

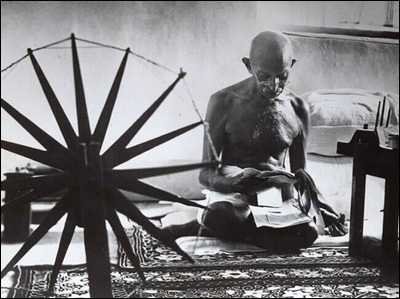

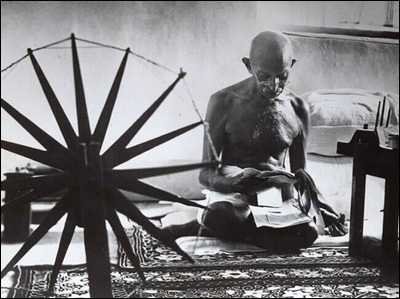

To see the universal and all-pervading Spirit of Truth face to face one must be able to love the meanest of creation as oneself. And a man who aspires after that cannot afford to keep out of any field of life. That is why my devotion to Truth has drawn me into the field of politics; and I can say without the slightest hesitation, and yet in all humility, that those who say that religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion means.

Mohandas Gandhi, An Autobiography or, the Story of My Experiments with Truth

If one's relationship with God is political, every lesser aspect of life must be political also. Gandhi says as much in the above quote. He suggests that even Truth is political.

For Kesey—the iconoclastic artist—lived by a simple motto he clung to with the tenacity of a pit bull. The job of the writer, he said, is to kiss up to no one, "no matter how big and holy and white and tempting and powerful."

Douglas Brinkley, "A Final Word From the Last Merry Prankster," writing about Ken Kesey, LA Times, 11/18/01

Washing one's hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless means to side with the powerful, not to be neutral.

Paulo Freire, educator (1921-1997)

Related links

Defining great American literature

Indian comics: Art vs. propaganda

PEACE PARTY #2's Author's Forum (extended version)

Why write fiction: the power of storytelling

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.