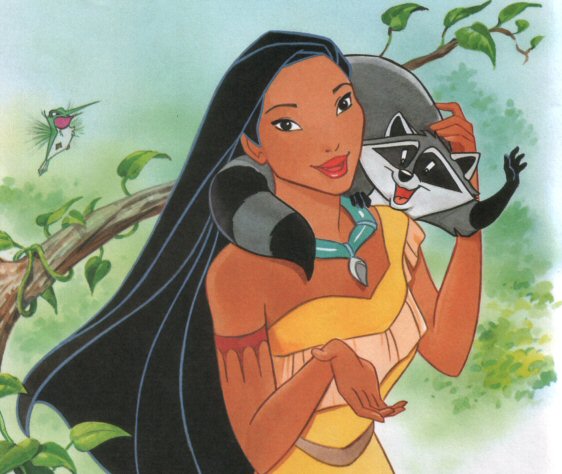

In the Fall 1998 issue of Red Ink magazine, Maura M. Little lists some of the problems with Pocahontas. These problmes include:

In the Fall 1998 issue of Red Ink magazine, Maura M. Little lists some of the problems with Pocahontas. These problmes include:

In the Fall 1998 issue of Red Ink magazine, Maura M. Little lists some of the problems with Pocahontas. These problmes include:

In the Fall 1998 issue of Red Ink magazine, Maura M. Little lists some of the problems with Pocahontas. These problmes include:

The message, as Little concludes, is that "Once again, the white male wins and proves his superiority over women and his status as protector of Indian people."

Rob's reaction

My reaction upon seeing the movie:

Is it okay to make up the lives of real, historical figures? To entertain kids, and not incidentally to profit, from twisting history? I don't think so.

Some say kids need "fairy tales" like Pocahontas to retain their innocence. If so, why shouldn't parents also make up fairy tales about the death of a relative or pet, an impending divorce, or a child's adoption? The answer is because psychologists say it's best to tell the truth. Even young children can tell the difference between fact and fiction. Knowing the facts helps assuage their doubts and fears.

Should we have children "make believe" about slaves singing and dancing on the plantation? How about a musical or comedy in which the Titanic doesn't sink after all? Why not? That's the same as fictionalizing the reality of Indian lives.

If Disney wants to stoke children's imaginations and help them make believe, let it create an entirely fictional story, as it did with A Little Mermaid. It's wrong for kids to make believe that Arabs are uncouth barbarians (Aladdin) or that women will only be happy when they get married (almost any Disney movie). Romanticizing Pocahontas's story is equally wrong.

No one would think of pretending that Abraham Lincoln didn't get shot or the Holocaust didn't happen. Why is this bastardization of history more acceptable? Because it's more distant in time and happened to "them," not to us? Ask the Powhatan Indians and their children, still living in Virginia, how much they enjoyed seeing the mistakes and stereotypes.

Most textbooks don't say much about the Pocahontas incident, so suggesting that children have plenty of opportunities to learn the facts is a dodge. Fact is, most children are likely to get most of their information from this movie. That imposes a moral responsibility on Disney to do more than just entertain.

That said, I thought the movie was visually gorgeous, the storyline entertaining, and the message positive. I'm old enough not to be seduced by Disney's party line: that life is only meaningful with romance and a happy ending. I'd recommend Pocahontas to older kids, but I'd watch it with them. And I'd tell them this isn't the way it happened.

The evidence of harm

From Steve Harvey's column in the LA Times, c. 1995-96:

When a portrait of a crinkly eyed Smith was shown on "Biography," our daughter Sarah, age 7, said, "Oh, my God! He's got a beard! He's almost bald!"

When a portrait of the Indian princess was shown, Sarah took one look at the somewhat plump, round-faced child and declared: "That is not Pocahontas."

During one commercial break, however, she exclaimed, "There they are," pointing triumphantly to the screen, where the voluptuous Indian maiden and surfer John were indeed frolicking. It was an ad for the animated movie.

And from another article in the LA Times, c. 1995-96:

The film's most important critics—those under 4-feet all—want to know why Pocahontas and John Smith couldn't live happily ever after.

"It was great, but I wanted them to be boyfriend and girlfriend," said Stephanie, 8, on Saturday.

"I didn't really understand why he wanted to go back to England," said Travis, 10.

"I liked the ending," said Erica, 5. "I liked the way Pocahontas ran to the top of the hill. But I would have liked to see her married."

These comments touch upon some of the points I and others have made. The kids obviously buy into the movie as a history lesson—except for the ending, because it rings false compared to the rest of the romanticized story. With its stereotyping (positive as well as negative, but still stereotyping), the movie creates expectations that its version is true and anything that contradicts it is false.

Also, the movie promotes the Disney ideal that fulfilment comes through being in love, and that a woman's primary goal is to be married. Note the subplot where Pocahontas is promised to the warrior Kocoum. She gets to choose between loves, not between love and, say, being chieftain.

One further point is that the movie reinforces the insidious notion that every story must have a happy ending to be satisfactory. This search for the easy answer, the quick fix, the short-term profit is part and parcel of the American psyche. It leads to such results as policing the Internet (just stop the smut-peddlers and bomber-terrorists, now!), the anti-flag burning amendment (who cares about diverse forms of speech? This is Old Glory we're talking about!), and abandoning Indian treaties (we tried to help them, but what can we do? They refuse to give up their failed cultures and join the mainstream!).

Yes, all this because of Pocahontas.... <g>

A correspondent comments (11/16/04)

A correspondent took me to task for treating Smith's rescue by Pocahontas as real. The following exchange ensued:

>> I'm writing in response to your comments on "Democracy Rocks." I realize this is pretty old, and I hope I don't offend you. But I just have to say, check your facts mate. <<

I've checked them. I've read Grace Steele Woodward's biography of Pocahontas and more.

>> You said that Pocahontas famously saved John Smith. <<

That the rescue is famous doesn't mean it actually happened.

>> Did you know, the only account of this is John Smith's written about 17 years after the fact. And that in his journal written shortly after his stay with the Pohatan he makes no mention of this. <<

Yes, yes.

>> The Pohatan people do not support this "historical" account. <<

They don't exactly deny it either. I read and linked to the Powhatans' response long ago. All it says is that scholars doubt the rescue happened.

>> Please don't fall prey to the "good Indian" stereotype that is subtly reinforced by this rhetoric. <<

That's somewhat ironic considering I've written essays on both Pocahontas and the "good Indian" stereotype.

Nevertheless, I don't think I covered the point that the whole rescue may have been fictional—and what the myth-making process says about our culture. I'll add something on that if and when I have time. Thanks!

Rob Schmidt

Publisher

PEACE PARTY

Did Pocahontas save John Smith?

The history...

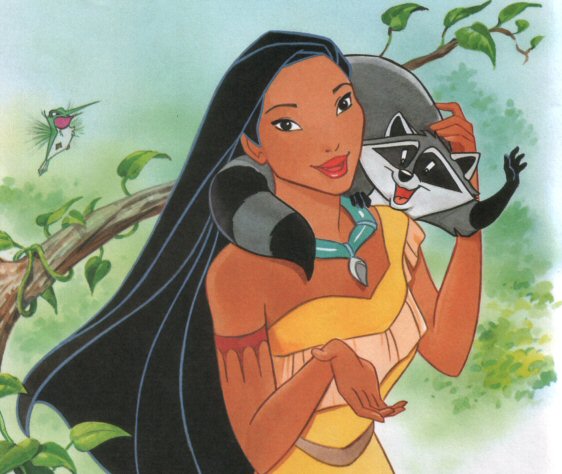

One of the most highly disputed issues in Smith's writings is his miraculous salvation by Pocahontas in 1607. Though he briefly told the story in the The True Relations (1608) and somewhat elaborated on it in later writings, the public first learned about the incident only in 1624, when the following account of it was included in The Generall Historie, that contains the most complete version.

... having feasted him after their best barbarous manner they could, a long consultation was held, but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could layd hands on him, dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beate out his braines, Pocahontas the Kings dearest daughter, when no intreaty could prevaile, got his head in her armes, and laid her owne upon his to sabe him from death ...

(from an extract presented in Kuppermann, 64)

The significant time-gap immediately gave rise to speculations whether the events took place as described by him or, even worse, whether they took place at all. Smith himself claimed that he had related the story to Queen Anne in a letter in 1616, but, of course, the letter could not be found and Queen Anne had already died by 1624. Likewise all possible witnesses of the scene were either dead (Pocahontas, Powhatan) or could not be interrogated because the war (1622-1640) had made the Indians and the English enemies.What made him even more suspicious is the fact that his narration follows archetypal patterns. Smith's contemporaries knew such stories from Greek mythology (i.e.: Ariadne/Theseus) or from recent history. In 1529, for instance, Juan Ortiz, a Spanish soldier, was reported to have been saved under similar circumstances by an Indian girl in Florida. Thus Smith might just have invented his story following the outlines of similar stories in order to add a fictional quality to his otherwise dry historical writing. Theweleit suggests that Smith knew that for any writing to be attractive and effective it needs a fictional element.

Some critics have argued that Smith misinterpreted the situation completely, given that the whole scene ever took place: He never was in real danger, his execution was just staged. He had to die symbolically to be born again -- and here opinions differ greatly -- either as subordinate chief of the settlers, recognized by Powhatan, or as Powhatan's adopted son Nantaquoud. However unclear Pocahontas' role in this ceremony of initiation/adoption may be, her intervention has accordingly been interpreted as part of the ritual. Unfortunately there is no evidence for such ceremonies directly from the Algonkins, but some Northwestern tribes are known to have performed such death-and-initiation rituals. According to this interpretation Powhatan pursued a policy of integration during the early stages of white settlement. Yet the question remains unanswered why Smith did not relate these events in his report of 1608. Various answers have been given, such as that he might have been embarrassed to have been saved by a 12-year-old girl, or that political considerations could have forced him to keep silent or that the editor simply shortened the story, but none of them is convincing enough. Theweleit speculates that Smith tried to confirm his manhood in the manner of the popular story of the gentleman of the South, that he attempted to draw attention to him after a more or less uneventful, unsuccessful life in Europe and that he tried to portray a noble exception of a wild red girl saving a Christian.

Pocahontas, our founding mother?

...and the histo/myth-tory:

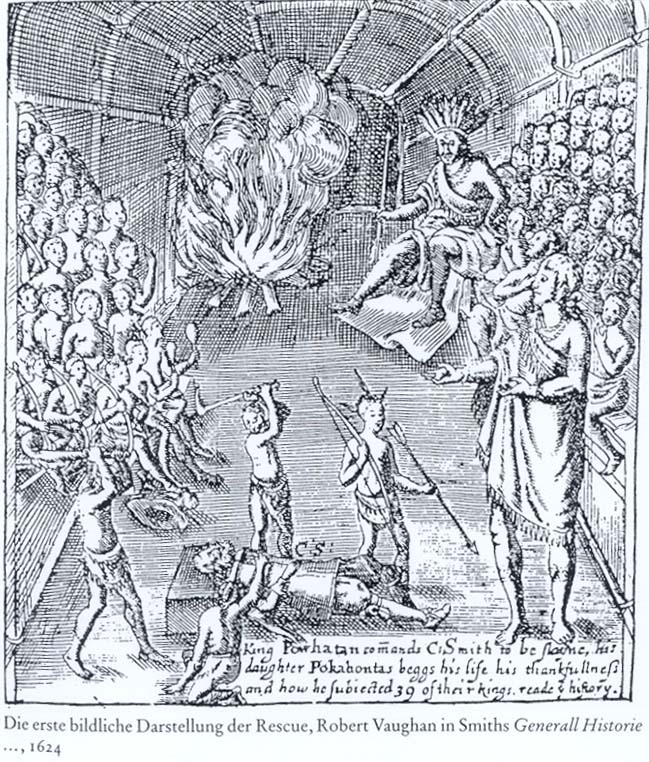

But there is a further aspect to this issue: Pocahontas and Captain Smith have entered mythology, and their relationship has become a popular myth whereas the marriage between Pocahontas and John Rolfe is far more less known. History consists of events that happened, did not happen and could/should have happened. Myth, on the other hand, only needs a center of facts to originate from (though of course Postmodernists and New-Historicists are sceptical about such a clear-cut distinction). The relation between Pocahontas and Captain Smith is more attractive and therefore more suitable to function as the core of a myth because of its sense of seduction and transgression. Quite in contrast, the marriage between Pocahontas and Rolfe is less sensational because it was legalised: she was baptized, educated and therefore was a full member of the Jamestown community. Secondly there is no evidence for a romantic affair between Pocahontas and Captain Smith, but the lack of facts makes the relationship even more attractive, it leaves room for speculation and fabulation.

.

.

.

In this case, America has an original, non-British mother who is noble enough to save her enemy, a distinguished Englishman. The union between the European hero and the Native American Princess was short, but harmonic and effective. The founding act itself has become mythological, undesirable consequences like the following expulsion of the Indians have not found a way into popular mythology. Through his writings Smith promoted himself successfully and became a pop-star. He made himself Siegfried, Odysseus, Aeneas and created the core for a story that perfectly satisfied various needs over the centuries. Pocahontas has become the mother of the New World. She symbolizes the birth of a new generation arising from the union of distinctive Native American and European heritage. John Rolfe did not enter the myth- and story-making of America's founding because he is too traceable, too real. Also his connection to the history of tobacco, the driving away of the Indians and the more or less forceful Christianization of Pocahontas is not really desired in the presentation of America's origins until today.

According to Theweleit it was John Davis, who first created a mytho-literary life of Pocahontas. In 1805 he published three novels, in which he focused on her as the romantic heroine of a love story: The first settlers of Virginia, an historical novel; Captain John Smith and Princess Pocahontas, an Indian Tale; Pocahontas. He wrote a whole series of books, of which the last one, The life and surprising adventures of the celebrated John Smith, first settler of Virginia, was published in 1813. Pocahontas, highly romanticized by him, is a heroic and virtuous character, her features are in accordance with white standards. In other words, in this presentation she has lost her Indian identity.

.

.

.

What people like Cooke and Henry ultimately tried to do was to maintain the foundation myth of Virginia in the face of the Northern equivalent, the story of the Pilgrim Fathers, who arrived in New England only in 1621. The history of their settlement found entry into the schoolbooks as the model of early settlement, whereas the history of the first settlement in Jamestown was denigrated its historical status and instead confined to the realms of mythology, song and literature. Such efforts were in vain, they were even counterproductive because Pocahontas was simply absorbed by the dominant, that is Northern, discourse, and became an integral part of the Plymouth Culture as Theweleit puts it. Pocahontas became the mother of the whole union.

What people like Cooke and Henry ultimately tried to do was to maintain the foundation myth of Virginia in the face of the Northern equivalent, the story of the Pilgrim Fathers, who arrived in New England only in 1621. The history of their settlement found entry into the schoolbooks as the model of early settlement, whereas the history of the first settlement in Jamestown was denigrated its historical status and instead confined to the realms of mythology, song and literature. Such efforts were in vain, they were even counterproductive because Pocahontas was simply absorbed by the dominant, that is Northern, discourse, and became an integral part of the Plymouth Culture as Theweleit puts it. Pocahontas became the mother of the whole union.

After the Civil War the North rewrote not only its own history but also the history of the whole union. The 250th anniversary of the arrival of the Pilgrim Fathers at Plymouth in 1871 was a perfect occasion for the Northerners to stress the moral superiority of the Pilgrims (and thus of themselves) to Smith and his companions (meaning of course the Southerners) in their oratories. In Theweleit's opinion this was the birth of the American religious moralism that insists on moral superiority as being the core of the victory of the white North over the transgressing South. This feeling of superiority has been hidden differently at different times. For the purpose of justifying the Civil War properly it was covered by the popular desire to fight salvery. The process of renaming this moralism experienced various stages of which today's campaign against tobacco (being produced in the South) is only the last instance.

Buy it now

Curious about the movie Pocahontas, which Rob rates an 8.5 of 10? Click here to get it now.

Pocahontas in the Stereotype of the Month contest

eBay auctions Red Indian girl, squaw, Pocahontas costumes

Pocahontas promo: "Paint your face/Pitch your tee pee"

Pocahontas toy depicts princess, chief, teepees, weapons

Williams's Oscar line: "Pocahontas is addicted to craps"

Disney Store sells Pocahontas costume with wig and fringe

Order of Red Men has Chiefs, Prophet, Pocahontas annex

Students wear crowns of feathers, sing Pocahontas songs

3 Wishes Lingerie features Naughty Navajo, Sexy Chief

Pocahontas Barbie looks like Vegas showgirl/harem girl

Zippy comic strip shows big Pocahontas beside teepee

Website costumes people as Sitting Bull and Pocahontas

Online stores sell Indian "warrior," "princess" costumes

More on Pocahontas, John Smith, and Virginia's Indians

Pocahontas [from the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities]

Captain John Smith Is Saved by Pocahontas, 1608

Pocahontas, Truth and Myth

Did Pocahontas Save Captain John Smith?

Pocahontas's other marriage

Review of The Princess Pocahontas

Misconceptions about Virginia's Indians

Good question on Pocahontas

Pocahontas's society was complex

Pocahontas in Harry Potter

NOVA lays Pocahontas bare

Preview of Pocahontas Revealed

Pocahontas overshadows Virginia's Indians

Mixed feelings about Pocahontas

Was Pocahontas raped and murdered?

Pornographic Pocahontas

The first Indian princess?

Dreams of historical romance

More on Disney's Pocahontas

Sexy, superior Pocahontas

German version of Pocahontas

Jessica Biel as Pocahontas

The Pocahontas Myth: The Powhatan Indians' view of the Disney movies

Indian opinions about Pocahontas

Pocahontas II: flawed again

"Marriage or bust" for Disney's women

Terrence Malick's The New World

New World, old myth

More on Jamestown

Tribal showcase at Jamestown

Jamestown at the Hungtington

Jamestown as foundation tale

"Melting pot" explained

The real message of Jamestown

Invasion of America = invasion of Iraq?

Commemorative Jamestown coins

Pat Buchanan on Jamestown

Commemorating Jamestown, then and now

Indians at Jamestown, then and now

Learning from Jamestown

Protesting at Jamestown

Queen Elizabeth reflects

Virginia's Indians tout "mythology"?

Jamestown 50 years later

Jamestown represents America

Queen to apologize for slaughter?

Jamestown ignores Pocahontas

4th graders learn truth

Over-the-top Jamestown parody

Why Plymouth, not Jamestown?

Colonists who eat colonists

Webcast explores Virginia history

America's first multicultural village?

Related links

Indian women as sex objects

Democracy rocks—with Indian help

Gingrich flunks "American Culture"

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.