Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

Winning Through Nonviolence

(2/19/01)

You have learned that they were told, "Eye for eye, tooth for tooth." But what I tell you is this: Do not set yourself against the man who wrongs you. If someone slaps you on the right cheek, turn and offer him your left.

Jesus, quoted in Matthew 5:38-39

An eye for an eye and the whole world goes blind.

Mohandas K. Gandhi

All tremble at violence; life is dear to all. Putting oneself in the place of another, one should not kill nor cause another to kill.

Buddha, "The Dhammapada" (a collection of the Buddha's essential sayings)

I strongly reiterate that the ways of violence will never lead to genuine solutions to humanity's problems.

Pope John Paul II, statement, 9/12/01

*****

Commitment to nonviolence works

From Michael Lerner's column on the Palestinian struggle against Israel. In the LA Times, 2/16/01:

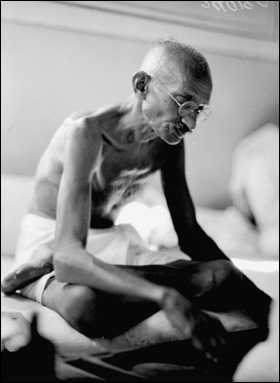

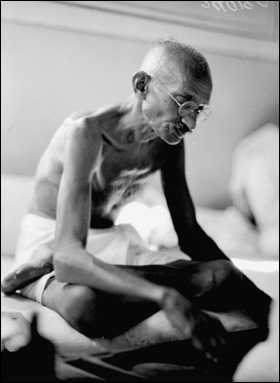

The most successful struggles waged against oppression of this sort have been those that have had a principled commitment to nonviolence. The Palestinian people should learn from and follow the example of Martin Luther King Jr., Mohandas K. Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. In the final analysis, all those struggles were won because the nonviolence of the oppressed touched something deep in the hearts of the oppressors, dividing the community of those who were militarily more powerful and creating a sense of moral obligation to listen to the needs of the less powerful.

Violence, on the other hand, unites the occupier's community and gives justification for using violence against the oppressed. It's no use to say, "Well, they were doing that anyway." If the goal is to undermine the ability of the superior military force to continue to act immorally, the occupied need to claim the higher moral ground, and that can be done only with nonviolence.

And there is another reason to reject violence: because it's morally wrong. The Palestinians who engage in violence are not only doing something that is self-destructive and stupid, but they also are doing something that is a moral outrage. Every human being is equally precious to God. Communicating that human life is sacred is the first step toward persuading your antagonist that real reconciliation is possible.

When will this madness end? If history is any indication, the occupation is a lost cause. Eventually, the Israelis will be forced to give up occupying another people. But that won't happen until the Palestinians have mobilized world opinion on their behalf, and that they cannot do while engaged in acts of violence.

In arming [Arafat] and giving him the ability to be the representative of the Palestinians, the Israelis cynically assured that they never would have to face the one thing that could defeat them: a morally based, nonviolent population willing to engage in massive nonviolent civil disobedience over a sustained period of time.

Commitment to violence doesn't work

After a wave of Palestinian suicide bombings and Israeli military reprisals, has violence solved anything? No. From the LA Times, 8/11/02:

ISRAEL

Military Option Has Run Its Course

By AMY WILENTZ

At a recent U.N.-sponsored conference in Copenhagen on peace in the Middle East, I was shaken at how old-fashioned and out of touch the peaceniks seem now, isolated on a planet and in a time warp of their own. Back in the old days, the peace camp had lofty goals and a plausible agenda; now, it seems like any other special-interest group, a bunch of sadly familiar figures pushing a recondite objective, using an idiosyncratic and shopworn language that corresponds to no other, a whole lexicon of terms, of tropes, conventions, formulas, code words and shorthand that hardly any but the expert can interpret.

They measure history in an encrypted atlas: Madrid, Oslo (I and II), Camp David (I and II), the White House lawn (famous to them for "the handshake"), Wye Plantation, Taba (I and II). Violence too has its nicknames, which get traded around at peace conferences like Chance cards in Monopoly: Baruch Goldstein, the No. 18 bus (one and two), Dizengoff Center, the central bus station (one, two, three and four), Mohammed Dura, Shalhevet Pass, and now the Dolphinarium, Passover, Jenin, Salah Shehada, Frank Sinatra cafeteria.

The participants talk about resolution number this and resolution number that, and about timetables, breakdowns, deadlines and cutoff dates. They babble vainly on.

And yet, I count myself among them, more so now than ever.

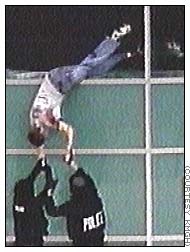

Israel has reoccupied the West Bank. It has bombed the headquarters of the Palestinian security forces in Gaza and on the West Bank. It has raided supposed bomb-making facilities and arrested or killed alleged bombers and potential bombers. It has demolished the homes of the families of bombers and reputed bombers. It has demolished the refugee camp at Jenin and bombed the neighborhood of one Hamas mastermind, so far. It is planning to exile the families of suicide bombers from the West Bank to Gaza (one wonders what it plans to do to suicide bombers' families who live in Gaza—perhaps exile them to Gaza also?). It has cracked down ruthlessly on movement across the West Bank and has instituted harsh curfews in the big towns. It has begun building a fence (only about 120 feet, so far, out of more than 200 miles, but time is measured differently in biblical lands) between what it calls Israel and what are called the Occupied Territories.

Still the suicide bombers come, more and more. This means, and Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and the Israelis must eventually realize it, that a military/physical solution is not practicable. Or perhaps, it is practicable (meaning you can do it), but it simply won't work—if security for Israelis is your goal. If remaining in power is your goal, if drumming up nationalist fervor is your goal, then perhaps the military option is serviceable. But if protecting your people is your goal, then Sharon's Palestinian policies have obviously been a big failure.

This is a tough one for the Israelis, who probably always imagined that their evident military superiority would serve in any serious test of wills to protect them more or less utterly. Even the peaceniks on the Israeli side secretly harbored this belief. Perhaps they were imagining their military power as it might have been wielded by a leader of subtlety and nuance, a leader capable of to and fro, a leader with a certain degree of moderation, which is not what they voted into office, and not what they have. Sharon has taken every opportunity to destroy the possibility for peace, has stomped on every little shoot of dialogue. He is like a mad elephant rampaging through a small, ancient village carefully built by elders out of mud and sticks. Wherever he goes, everything is destroyed.

He is trying to destroy hope and build a nationalist camp based on statewide despair. His policies are making the Israelis hopeless while, at the same time, enabling the worst elements in Palestinian society, pushing them to new heights of cruelty and making that cruelty more palatable to a broader range of the Palestinian population. This is good for Sharon, who has caught the Israelis in a circular bind of logic in which they accept more and more violent means to quell the kind of violence that instead is pumped up under attack.

To blame Sharon for all this is not to blame the victim. Sorry. To blame him is to blame one of the main perpetrators. But what's more interesting is what his role might turn out to be, because all leaders both create and are influenced by the stream of history in which they find themselves. I like to think, when I'm fanning my weak spark of optimism, that there is another fate for Israel than that of an armed, walled fortress, oppressing its neighbors and being attacked and sabotaged by them, forever. I like to imagine, as I blow on the dying embers, that what Yossi Beilin (the much-maligned and marginalized peace technocrat, and a perennial figure at peace talks, conferences, secret meetings and negotiations) believes is true. That, as the masters say in chess, because the endgame is already preordained, worked out and on paper (from the days of "Oslo" and "Taba"), all it takes to get there is to step gingerly and cleverly through the soggy, swampy, ambushed middle of play. I even nourish a sick hope that perhaps Sharon has boxed himself into a corner where he will end up being the one to sign the peace. An indication that that's the direction in which things are going: last week's near-agreement between the Israelis and the Palestinian leadership (whoever that is) concerning security and what I like to call "de-reoccupation." True, it didn't happen. But they are talking.

Except for President Bush, the international community supports a peace initiative. (Bush says he does, too, on his better days, but he has boxed himself into his own foreign-policy corner with his war on terror.) The Quartet—the U.S., Russia, the European Union and the United Nations—is working toward that goal, as is the Trio, composed of Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Egypt. Quartet and Trio, more words from the peaceniks' lexicon, but still, they exist.

It's tragic that Sharon's ill-conceived "plan" for Israel's security can only be shown to be unsuccessful because the suicide bombers are still lining up inside Israel to kill more Israelis. All the peaceniks said this would happen, from the beginning. That's because the peaceniks know the Palestinians and have been talking to the Palestinians for years. Sharon, apparently, doesn't, and has misjudged the Palestinians every which way, although he certainly knows how to push their buttons.

Sometimes a situation has to reach a nadir before people realize what they ought to have realized before, but did not choose to. The Israeli right didn't want to make peace with the Palestinians because it did not think it had to. Israel was stronger, remember? Today, a small but important segment of the Palestinian population has repudiated suicide bombing publicly. In Israel, too, there is a tiny resurgence of debate. Strength, the Israelis have seen once again, resides in many characteristics. Not just firepower, but also tenacity. Not just ruthlessness, but also desperation. The Hamas/Sharon combination—a melange of suicide bombing and bombing tout court—has brought us to where we are now. We are at the end of Israel's military option, as the destruction of Shehada's neighborhood and neighbors has shown us. Perhaps Israel is willing to go farther down the dangerous military path, but even its best friends will agree for only so long (witness Bush's reaction to the Shehada bomb), and then Israel will be on its own.

That's not a safe place to be.

Copyright 2002 Los Angeles Times

The violence solution gets tested

With the 9/11/01 terrorist attacks on the US, the Israeli/Palestinian conflict suddenly became an international conflict. The US and its allies had a chance to practice what they preached. If the US was the world's moral leader, it could've taken the high road and eschewed violence, much as it asked Israelis and Palestinians to do in their conflict.

Naturally, that didn't happen. The US, with its cowboy-warrior mentality, immediately sought bloody vengeance. "President" Bush declared war—it's not clear against whom—and said America would lead the world to victory.

If Bush is lucky, he won't mire the US in another Vietnam. Or perhaps the US needs another Vietnam, to reinforce the lesson that's fading from memory. Violence hasn't changed anyone's mind in a long time—not since World War II, arguably.

Here's what a couple of pundits had to say on the prospect of violence for Israel and the US:

We've had too many years of experience of answering these kinds of attacks with more violence. And you know what? It hasn't worked. If we're serious about ending attacks like this, we have to go to the root causes.

The example is that when you respond with violence for violence it does not stop the terrorism.

Ending occupation of the West Bank and Gaza and East Jerusalem might make some difference. But certainly what isn't working is responding with more violence.

Our violence vs. their violence

An expert on peace discusses how we compartmentalize violence into "good" and "bad," ignoring the consequences when it suits our ideological outlook. From the LA Times, 9/18/01:

COMMENTARY

Violence Breeds More Violence

By COLMAN McCARTHY

Colman McCarthy, director of the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington, teaches nonviolence at Georgetown law school, American University and the University of Maryland.

In the field of conflict resolution, there are two types of violence, hot and cold.

Hot violence is the death and chaos of this past Tuesday in New York and Washington. Hot violence is the Columbine High School massacre, the Oklahoma City bombing. The unspeakable horror is up close and visible; witnesses' emotions are felt; outrage is immediate; media are quick to the scene.

Cold violence has little of that. It is beyond our view, so routine as to stir few emotions, so ordinary as to attract the media only rarely. Cold violence is the worldwide daily death toll of an estimated 40,000 people from preventable hunger-related diseases. But that is a distant and unseen reality, not an American reality, not the destroyed World Trade Center reality. Cold violence is the dying of Iraqis every day caused by U.S.-imposed economic sanctions. We learn to compartmentalize. Two days after the Colorado school killings in April 1999, President Clinton went to a public high school in Alexandria, Va., to speak to a student peer mediation club: "We must do more to reach out to our children and teach them to express their anger and resolve their conflicts with words, not weapons."

After the talk, he returned to the White House to order up the most intense bombing of Belgrade since U.S. and NATO pilots were turned loose a month before. In speeches, Clinton would call for alternatives to school violence while continuing to justify the military violence on Yugoslav civilians in their homes, offices and neighborhoods. His weapons that killed thousands were good. The weapons of schoolhouse shooters were evil.

The president's thinking was revealed in "All Too Human" by former White House advisor George Stephanopoulos. When told in October 1993 that U.S. soldiers had been killed by street fighters in Somalia, Clinton said: "When people kill us, they should be killed in greater numbers. I believe in killing people who try to hurt you, and I can't believe we're being pushed around by these two-bit" guerrillas. All of this fits the pattern of double-standard ethics. Hot violence tends to be illegal and unofficial. Cold violence, legal and official.

In "The Respectable Murderers," a classic text on nonviolence, Monsignor Paul Hanley Furfey, the Catholic University sociologist, wrote: "The sporadic crimes that soil the front pages, the daily robberies, assaults rapes and murders, are the work of individuals and small gangs. But the great evils, the persecutions, the unjust wars of conquest, the mass slaughters of the innocent, the exploitation of whole social classes—these crimes are committed by the organized community under the leadership of respectable citizens."

The solution? Withdraw support—political, financial and emotional—from all double-standard practitioners of violence, hot or cold, illegal or legal. Transfer the support to those working to eliminate violence, no matter where it is found or who is madly justifying it. This is an apt moment, as retribution hysteria grows and the ethic of hit-'em-back-harder is sounded like a battle station bugle call.

The nonviolent response to Sept. 11 is in the tradition of Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Dorothy Day, Jeannette Rankin and groups like the Fellowship of Reconciliation and Pax Christi. It is saying to those behind the attack: We forgive you; we reject vengeance. And then, summoning still more moral courage, to ask them to forgive us for all of our violence—for being the world's major arms peddler; for having a military budget many times greater than the combined military budgets of our alleged enemies; for our bombing of Grenada, Libya, Panama, Somalia, Iraq, Sudan, Afghanistan and Yugoslavia; for supporting dictators; and for blindly believing the jingoism of President Bush, who said, "Our nation is chosen by God and commissioned by history to be a model to the world."

A model for what? Vengeance, retribution, score settling? In the minds of the hijackers, that's what Sept. 11 was about. To perpetuate it from here is to guarantee more eyes for eyes.

In a similar vein, Ray Greene wrote about "'Our' Violence Versus 'Theirs'" (see Pop Culture: Time to Get Serious). Here's how he described America's bully-boy cry for violence after 9/11:

It is the cry of "our" violence, which is always appropriate and moral, against "their" violence, which is categorically without motivation and insane.

More thoughts about the cycle of violence—an article about singer/storyteller Utah Phillips titled Preaching Pacifism Amid War. In the Sacramento News and Review, 11/29/01:

Viewing our presence in Afghanistan as part of "a cycle of retaliation, a cycle of revenge, for a terrible, awful thing that happened in New York, that's going to continue," he sees the Middle East conflict potentially escalating into a nuclear conflict.

But isn't that part of what our military effort now is about, destroying the terrorist network before they do get a nuclear bomb or other weapons of mass destruction?

Phillips reminds me that the U.S. is the only country to have used an atomic bomb against a civilian population, twice. He quotes Richard Nixon, that the only effect of the Peace Movement was to prevent him from using nuclear weapons in North Vietnam.

"This carnage has to stop, this idea if you're going to beat up on us, we're going to beat up on you," he says. "Kids do that in the schoolyard. You separate them and try to teach them a different way to do things."

After 9/11, the cycle continues

From Universal Press Syndicate

For Release: Week of June 28, 2002

Column of the Americas

by Patrisia Gonzales and Roberto Rodriguez

Get Them Before They Get You

Rare is the war that is not fueled by hate. War is most often waged to control other people's labor, natural resources and territories. But invariably, hate is the kindling. The Bush administration's new policy of permanent and pre-emptive war will require us to perpetually hate new enemies worldwide. The result, we fear, will not be simply more war, but a fundamental shift in human values and morality.

For this nation to claim the unilateral right to pre-emptively strike (with nuclear weapons) at its enemies, and to determine which leaders and nations are evil, points to aspirations of empire-building. Still, that's not what portends disaster for humanity. Our government seems to think that only we are capable of pre-emptive wars and covert assassinations, and that there are no consequences for such actions.

This new policy threatens to encourage belligerent parties everywhere to adopt a similar ethos that will spill over into all facets of life, including children's playgrounds. "Treat others the way you would like to be treated" will be replaced with "Get them before they get you."

Worse yet, we're being conditioned to feel good about this righteous hate. We've been taught to feel morally superior to our foes, so that we may kill without guilt. This is accomplished by dehumanizing our enemies and believing that we're waging a noble and divinely supported cause. (This is not the same as rightfully bringing perpetrators to justice.) This way, when civilians are killed, we keep in mind that they're not the actual targets and remind ourselves of our greater cause — stomping out evil.

Most wars are supported by the same mentality: We are good, they are evil. And we are but an instrument of God, Allah or the Supreme Being.

This war is different, we're told — yet we're still being conditioned to hate. But just who is the enemy? Arabs, Muslims, Middle Easterners, South Asians? For several decades, a Third World War — a bloody, protracted struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union — was waged, leaving in its wake millions of casualties throughout the Third World. Now the planet's remaining superpower is set to wage another world war that threatens not only to battle terrorism, but to put down legitimate insurgencies.

That's not to say terrorism isn't a real threat. It is. However, we could eliminate every terrorist alive today and still not come close to eliminating the breeding grounds of misery and hatred that spawn them. This administration seems unable to differentiate between terrorism and insurrection.

The military implications of this new ethos are obvious. However, the fundamental shift we are talking about threatens thousands of years of our evolving civilization. Like falling dominoes, every facet of life is affected, and we become a less safe and a more indifferent and dehumanized society. For example, more than 1,300 migrants have perished in the Southwestern desert since 1998 (a few dozen in the past week alone in Arizona). Their deaths, from heatstroke and dehydration, were preventable, but instead they're viewed as casualties to homeland security priorities. Too bad, right?

We're on the verge of becoming societies governed not by morality and just laws, but instead gripped by fear and obsessed with self-preservation.

Both criminals and average citizens may reason, "If I may get shot, why not shoot first?" That slippery slide to chaos and anarchy is held back by a very thin line, and historically, eventually replaced by a governmental iron fist.

The antithesis is learning to love all of humanity and upholding all life as sacred. Perhaps we should begin to love not only our neighbors, but also our enemies (as Jesus commands and as a reader reminds us). Perhaps we can take the time to create new friendships, particularly with those outside our borders who are subjected to poverty and exploitation. Perhaps we can resolve to help eliminate it.

The world's largest (G-8) nations should quit trying to give fish to the world's poor, or even trying to teach them how to fish. They already know how to fish. Instead, they should stop stealing and polluting the world's waters. This way we can all love each other righteously so that we won't later have to hate each other as enemies.

It's so much easier to hate.

Copyright 2002 Universal Press Syndicate

Evidence suggests why nonviolence works

Nonviolence isn't just a "nice" theory developed by ivory-tower eggheads. As Gandhi, King, and I have suggested, it's a winning long-term strategy. For examples of how not fighting—instead, talking and finding common points of interest—has worked at least as well as fighting, see Diplomacy Works, Violence Doesn't.

Theory helps explain why diplomacy works and violence doesn't. For instance, from K.C. Cole's column in the LA Times, 6/11/01:

In a series of now-classic studies, competing computer programs (computers can "play" faster than people) tried out various strategies for long-term survival. Those that put an emphasis on cooperation fared much better in the long run than those that employed competitive, confrontational tactics.

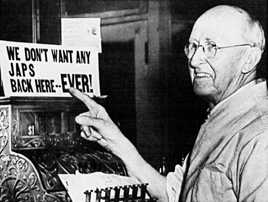

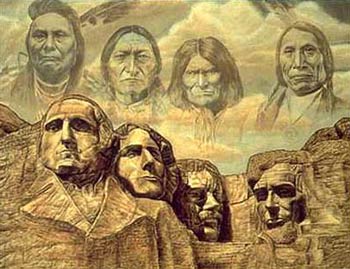

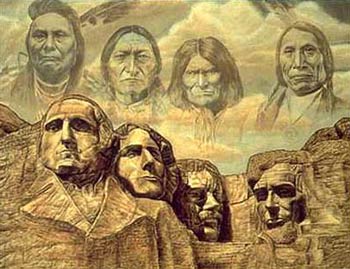

Indeed, Euro-Americans succeeded against Indian tribes precisely by dealing with them individually and turning them against each other. Witness the long series of wars in which in Indians took sides with the French, British, and Americans against other Indians. If they had stood united against the European invaders, they might've stood a chance.

See Was Native Defeat Inevitable? for more on the subject.

Media: problem and solution

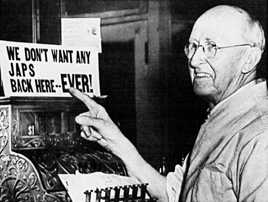

America was arguably born in violence, as Columbus killed or enslaved the Indians he met. This violence was perpetuated by the institutions of the time: government, churches, and civic groups. With the nation engaged in Indian wars and slave trading, who listened if a few pacifist Quakers urged another way? Certainly not Andrew Jackson, Theodore Roosevelt, and other expansion-minded leaders.

Today our primordial violence is perpetuated by today's institutions. The media has taken over as the key purveyor of violent words and images. Movies, TV, music, video games, the Internet, and other forms of media easily outshout America's parents, teachers, political and religious leaders.

Countless books and studies have analyzed how television and the movies have become dominant players in our hearts and minds. One article describes the problem and observes how the media also can be the solution. From the LA Times, 6/7/99:

Here's a Role for Hollywood: Showing the Power of Nonviolence

By ELLWOOD KIESER, C.S.P.

The tragedy at Columbine High, the White House summit on media violence and the plethora of studies that link the entertainment violence to real-life violence have occasioned a crisis of conscience in Hollywood.

One segment of the entertainment industry admits there is a problem. It knows that polluted airwaves are just as serious a national problem as polluted skies, oceans and forests, and it acknowledges its own role in that pollution. Another segment denies any connection and says it is simply reflecting the violence of our society. Like a whale that has been hit with a harpoon, it thrashes about wildly, seeking someone else to blame—parents for their irresponsibility, the viewing public for supporting violent shows; the networks and cable companies for catering to viewers' baser instincts; Congress for its cowardice on gun control and its threat to limit 1st Amendment rights.

After working in this industry for 39 years as both priest and producer, I have the feeling the harpoon carries too much truth, is too well aimed and has penetrated too deeply to be shaken off. The problem is going to have to be faced and dealt with. And eventually, I believe, the industry will responsibly rise to the challenge.

No one would maintain that television and motion pictures are the sole, or even the primary, source of violence in our society. Nor does any responsible person want to bridge the 1st Amendment, impose government censorship or categorically ban all TV or movie violence. The problem is not with media violence as such but with the superficial, distorted and exploitative way that violence is so often presented. Such a portrayal desensitizes its viewers to the horrors of real-life violence, arouses the aggressive and violent impulses that lie dormant in every human heart and conveys the impression that violence is an acceptable way to resolve conflict. Worse, it implies that human life is arbitrary, hostile and cruel, that other people are the enemy, that life is warfare and only the violent survive.

For years, film and TV shows reinforced racial and gender stereotypes. But then the industry was made aware of what it was doing and responded responsibly, with the result that Hollywood is now a major force in demolishing stereotypes and promoting racial and sexual equality.

For decades, American television and motion pictures promoted cigarette smoking. But then came the surgeon general's report, and the industry again responded responsibly. As a result, anyone who now smokes in public feels like a pariah.

If, as the studies contend and a subsequent surgeon general's report states, American movies and television are a significant cause of violence in our society, I think, in the future, they could become just the opposite: a significant contributor to the decline of violence in our homes and on our streets.

I am convinced they can do this in three ways.

First, they can take us into the psyches of the initiators of violence and help us experience the fear, isolation, self-hatred, despair and cowardice that most often characterize these people. Despite the characters played by Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, there is nothing heroic, healthy or happy about the perpetrators of violence. They are sick. Who would want to be like them?

Second, what the news clips do for the carnage in Kosovo, television and movies can do for the carnage here: show us the horrendous effects of real-life violence on its victims, their families and on its perpetuators. Of those who engage in unjustified violence, only the most dehumanized do not feel intense revulsion at what they have done. And many of those who engage in justified violence suffer a degree of emotional havoc. No wonder police departments need resident psychologists.

Third, television and movies can illumine the necessity—and the rigors—of nonviolent conflict resolution. Confronting our adversaries. Being honest about our complaints. Listening. Trying to see the problems through their eyes. Affirming them—their intelligence and goodwill—despite the pain they may have caused. Appealing to the best in our adversary. Seeking the truth through honest dialogue, even if that should demand we change our position. Seeking justice for them as well as for ourselves, even if that should require we cut back on our demands. Resisting the temptation to manipulate, deceive or punish them.

Does nonviolence work? Of course. Look at the civil rights movement, Solidarity in Poland, the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, People's Power in the Philippines. And we have all seen the kind word, the loving gesture transform the potentially hostile person into a friendly one.

Is nonviolence easy? No way. It requires trust in the truth and in the basic goodness of even the most debased human being. It requires great moral stamina to forgive, to let go of the hatred that clogs the arteries of the soul. And it requires a rare kind of courage to love one's enemy, endure suffering rather than inflict it and meet physical force with soul force.

Does nonviolence give writers and producers the raw materials they need to create entertaining stories? Absolutely. All the elements of compelling drama are present: intense emotional conflict, sympathetic characters with whom the audience can identify and for whom they can root, high-stakes jeopardy and suspense.

If nonviolence is so theatrical, why have we in the creative community been so loath to present it? I think it is because, rightly or wrongly, we have convinced ourselves that nonviolent conflict resolution demands too much of our viewers, that it contains more truth than they are able or willing to handle.

That is the perennial temptation for Hollywood's creative community—to give the audience the partial truth it wants to hear rather than the whole truth it needs to hear.

We have succumbed to this temptation in the past. We cannot afford to do so in the future. With our stories we have shattered racial and gender stereotypes. We have given smoking a bad name. I do not see why we cannot do the same with violence. Instead of contributing to the problem, we can contribute to the solution.

This can happen if we begin to trust our viewers and tell them the whole truth about violence, and if our viewers, in huge numbers, support us in this effort.

Ellwood Kieser, C.S.P., is president of Paulist Productions and producer of "Insight," "Romero," and "Entertaining Angels." He also is president of the organization that hands out the annual Humanitas Prizes to writers of films and TV programs.

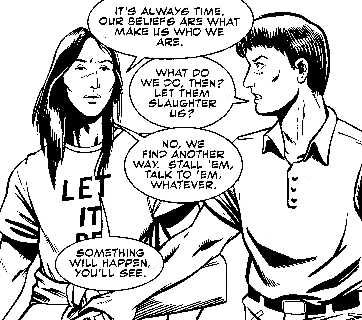

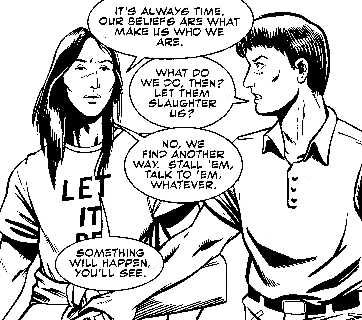

Meeting physical force with soul force is exactly what happens in the first PEACE PARTY adventure. We're doing our part to fight America's love of violence with faith, hope, and charity, not to mention intelligence, wit, and style. Our characters will kick butt, figuratively speaking, without dragging or bruising their knuckles.

More quotes for peace, against war

Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.

Jesus, quoted in Matthew 5:9

Weapons are the tools of violence;

all decent men detest them.

Weapons are the tools of fear;

a decent man will avoid them

except in the direst necessity

and, if compelled, will use them

only with the utmost restraint.

Peace is his highest value.

If the peace has been shattered,

how can he be content?

His enemies are not demons,

but human beings like himself.

He doesn't wish them personal harm.

Nor does he rejoice in victory.

How could he rejoice in victory

and delight in the slaughter of men?

He enters a battle gravely,

with sorrow and with great compassion,

as if he were attending a funeral.

Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

War is a contagion.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, speech, October 5, 1937

War nourishes war.

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller, The Death of Wallenstein, 1798

Opposing ordnance roar

Across the swaths of slain,

And blood in torrents pour

In vain — always in vain,

For war breeds war again!

War Song, John Davidson (1857-1909)

One is left with the horrible feeling now that war settles nothing; that to win a war is as disastrous as to lose one!...We shall not survive war, but shall, as well as our adversaries, be destroyed by war.

Agatha Christie, An Autobiography, 1977

There never was a good war or a bad peace.

Benjamin Franklin, letter to Josiah Quincy, September 11, 1773

It hath been said that an unjust peace is to be preferred before a just war.

Samuel Butler, Butler's Remains, 1759

Never think that war, no matter how necessary, nor how justified, is not a crime.

Ernest Hemingway

Controversies must be resolved not by recourse to arms but by the peaceful means of negotiation and dialogue.

Pope John Paul II, speech, 9/22/01

Peace is not an absence of war, it is a virtue, a state of mind, a disposition for benevolence, confidence, justice.

Benedict Spinoza, Theological-Political Treatise, 1670

Peace is not merely a distant goal that we seek, but a means by which we arrive at that goal.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Nonviolence is the answer to the crucial political and moral questions of our time; the need for man to overcome oppression and violence without resorting to oppression and violence.

Martin Luther King Jr., speech accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, December 11, 1964

Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everyone blind. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding; it seeks to annihilate rather than convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends by defeating itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Overcome the angry by non-anger; overcome the wicked by goodness; overcome the miser by generosity; overcome the liar by truth.

Buddha, "The Dhammapada" (a collection of the Buddha's essential sayings)

When I despair, I remember that all through history the way of truth and love has always won. There have been tyrants and murderers and for a time they seem invincible but in the end, they always fall—think of it, always.

Mohandas K. Gandhi

The opposing viewpoint

I should welcome any war. The country needs one.

Theodore Roosevelt, assistant secretary of the Navy, letter to Henry Cabot Lodge, 1897

More on peace and nonviolence

Should Natives kill to save trees?

Indigenous peacemaking

Running for peace

Peace march signs: Some of the signs the 500,000 marchers had made and were carrying

Related links

Turning the other cheek

Diplomacy works, violence doesn't

Violence in America

America's cultural mindset

Readers respond

"After reading what you have written, I do not see how the term 'peace' applies."

"What to do if you happen upon a peace rally by stupid naive hemp-shirt-wearing college idiots...."

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.