An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay New World, Old Myth:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay New World, Old Myth: An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay New World, Old Myth:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay New World, Old Myth:

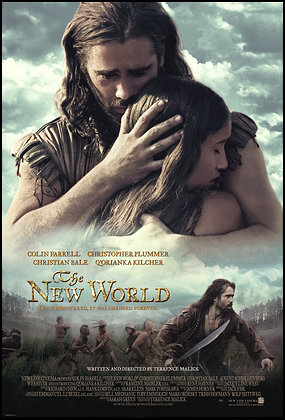

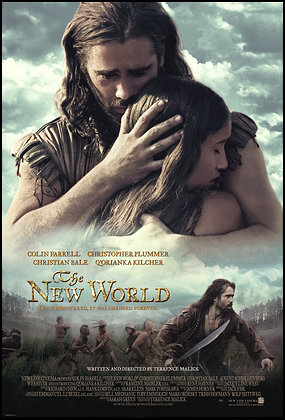

Some reactions to Terrence Malick's "The New World," a retelling of the Pocahontas myth that premiered in December.

The good

By Kirk Honeycutt

Bottom line: An evocative yet slow-moving exploration of the Pocahontas myth.

Terrence Malick's "The New World" is a visual tone poem orchestrated around the themes of innocence, discovery and loss. The inspiration is the historical legend of the "Indian princess" Pocahontas and English soldier of fortune John Smith. Malick has tried to base much of his vision on the historical record, delving into the writings of explorers and colonialists in early Virginia to create voice-over monologues by Smith and others. But this is resolutely a film of the imagination. As with all films in Malick's slim body of work, its imagery, haunting sounds and pastoral mood trump narrative.

Clearly "The New World" takes an audience into the rarefied atmosphere of an art film made with a studio budget, making its boxoffice impact hard to assess. The 150-minute film opens Christmas Day in Los Angeles and New York, then expands Jan. 13. Its slow, bucolic rhythms and unwillingness to exploit the violence or sex inherent in the story — the film nevertheless carries a PG-13 rating for its battle scenes — relegate the film to audiences devoted to Malick's work and film esoterica. In that world, it may become a hit.

The historical record — especially on the Native American side, where no written language exists — is skimpy. Nevertheless, Malick and production designer Jack Fisk bring us into a primeval Eden that feels credible. The weirdly painted natives and white-skinned, armor-clad intruders eye one another suspiciously. Their worlds, goals and beliefs could not be more antithetical.

The natives have little sense of possessions or greed but do have a strong social order. The settlers, most unprepared to deal with a wilderness, seek riches, regard each other with envy and mutiny at a moment's notice. A violent clash is inevitable.

John Smith (Colin Farrell) is first seen in shackles on one of three English ships that reach the James River in 1607. He has been insubordinate but is too valuable a soldier and survivalist to lose to a hanging. So Capt. Newport (Christopher Plummer) frees him upon arrival in the New World. He even gives Smith a key assignment before the captain returns to England for supplies.

Smith leads an expedition upriver to contact a native chief in hopes of establishing trade. Instead his men are killed, and he is taken prisoner. His life is spared by the chief (August Schellenberg) when his favorite daughter, Pocahontas (Q'Orianka Kilcher), begs for mercy. The chief releases Smith to this teenager so the two can learn each other's language and he might gain insight into the newcomers' intentions.

What they do, of course, is fall in love. Here the movie enters a dreamlike state, a nearly dialogue-free, lengthy montage composed of the physical world of the Virginia circa 1607. (The film actually was shot in that state.) As a strong bond is formed by two absolute strangers, they take in the richness of landscape and sounds of wind and birds in the forest. What would be unspeakably corny in the hands of a less masterly filmmaker works here because of Malick's absolute fidelity to the underlying emotions.

Smith returns to a crude fort with provisions supplied by the Indians. But his homecoming is like awaking from a dream into the ugliness and pettiness of the coarse settlers. When the settlers plant corn and thereby tip off the native chef that they intend to stay, he prepares to attack. But his daughter warns her lover, and the assault is thwarted.

The natives' heartbroken leader banishes his daughter, who then falls into the hands of another tribe that eventually trades her to the whites as an "insurance policy." Smith vehemently opposes this trade, which causes the ungrateful colonialists to depose him as their leader.

After the return of Capt. Newport, Smith is called back to England to lead other expeditions while the Indian girl adopts to living among the whites. Believing Smith to be dead, she marries newly arrived aristocrat John Rolfe (Christian Bale) and has a child. Much later, the couple travels to England, where this "princess" is introduced to the British monarch. Here she sees Smith for one last time.

While the name Pocahontas is never mentioned — the settlers ridiculously name her Rebecca — the film is essentially a love letter to the idealized myth of this historic woman, who is viewed here as both forest naif and earth mother. Malick and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki cover Kilcher with more loving poses and angles than a photographer doing a fashion spread. Kilcher is a striking young woman, and the camera — and perhaps Malick himself? — falls in love with her.

The movie has a restlessness as it moves through this story with a meandering camera, inner monologues and shifting points of view. James Horner's sumptuous musical score, incorporating bits of Wagner, Mozart and others, emulates the steadiness of the wind while its repetitive refrains remind one of Philip Glass. The camera lingers on details of frontier life, but the exploration here is less scientific and historical than a spiritual quest for what was lost and what was gained in this clash of civilizations. Certainly, the Westernization of this native woman presages the fate of North American natives and the despoiling of their paradise.

Farrell looks uncomfortable in the role, seldom changing expression and shifting his body aimlessly. Kilcher is quick-witted, full of 15-year-old life and possesses fine instincts despite being a newcomer to acting. Bale underplays his role, letting his innate goodness seep slowly out. In the native roles, Schellenberg and Wes Studi capture the dignity and ferocity of warriors fighting to retain a way of life. David Thewlis, Yorick Van Wageningen and others ably portray the avarice and aggressiveness of the newcomers.

From the LA Times:

MOVIE REVIEW

'The New World'

Malick deftly navigates a sensual, vast "New World."

By Carina Chocano

Times Staff Writer

December 23, 2005

"THE NEW WORLD" is Terrence Malick's fourth film in 32 years, basically consolidating his position as the least prolific, most interesting director working today. The movie is both a continuation of his work so far and its culmination, which doesn't make it any easier to talk about. Words, actually, don't have much to do with the effect it has on the senses. Like his previous movies — "Badlands," "Days of Heaven" and "The Thin Red Line" — "The New World" doesn't resist interpretation so much as it wanders away from it in an incandescent brume of wonder, dread and awe. It's a primal experience about the experience of primacy, if you'll forgive the fancy tautology.

If you won't, then you might be frustrated by the movie. There's bound to be — there always is — a range of reaction, just as, no doubt, the movie will be broken down by some into discrete components for greater ease of valuation. This, in my opinion, is a little akin to looking a gift horse in the mouth when you've never seen a horse before. Malick is an artist with a singular vision and the skill and support (one hopes) to realize it, and to apply conventional Hollywood standards to his films is to miss their point. He uses sound and imagery to create a vast sensory universe unfiltered through received notions, current politics or moral judgments and historical hindsight. He doesn't attempt to re-create a period so much as he tries to experience it for the first time, drawing human-scale characters against the enormous and cataclysmic backdrop of nature and history. What we get is not an "objective" or dispassionate view of the world but rather a series of subjective, experiential perspectives. He neither strives for verisimilitude nor spectacle but for an alchemic blend of both — life in all its power as it is experienced by sentient, sensitive beings.

Captain John Smith (a very good Colin Farrell) travels to Virginia aboard one of three ships financed by the London Virginia Co. along with 102 other men in search of gold. What they find instead is an unspoiled Eden that inspires exalted philosophical reveries about the possibility of forming a new, enlightened society based on justice, equality and shared prosperity. The society Smith envisions, in fact, shares much in common with the society he encounters there, even if not all of the recent arrivals share his view. For their part, the natives' astonished reaction to the Englishmen who are slowly infiltrating their landscape is laced with concern that has yet to blossom into worry. The scene of their first encounter conveys more wonder and dread than any alien invasion movie could hope for, no matter how impressive its special effects.

The brilliant cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki captures the grandeur and luminosity of the 1607 Virginia landscape in all its sensual glory, and Malick allows the experience to unfold like a slow dawn. Watching as scenes such as this one convey the strangeness and magnitude of human history and individual experience simply by pausing to observe, it's hard not to realize how little regard most contemporary films have for both. In all their rushing and jolting and artificial enhancement, most movies reveal a fierce anti-humanist streak, even a contempt for life — as though time were something to be sped up and wasted. But Malick is an explorer himself, with a talent for expressing the wonder of each new discovery.

The colonists' initial elation is short-lived, however, as conditions worsen, food becomes scarce and the men struggle to survive. Smith leads an expedition in search of food up the Chickahominy River, and along the way his group is attacked by the Powhatan tribe. His life is spared when Pocahontas (Q'orianka Kilcher), the beautiful and spirited teenage daughter of the chief, intervenes on his behalf, and Powhatan agrees to let him remain and teach the princess his language. Powhatan hopes that this will provide him some insight into the settlers' intentions. But as Smith acclimates to life among the tribe, he soon finds his ideas about man and society starting to shift and even considers the possibility of staying on to live among them. It's not just that he's fallen in love with the princess, who passionately requites his feelings. The civilization of "the naturals," as the English call them, comes to represent for him the possibility of a new way of being, a rebirth.

If the movie's dreamlike imagery, shifting inner monologues and sublime score by James Horner are best described as poetic, the movie's core is thoroughly philosophical. Malick is not interested in ferreting out psychological motivations to explain the movement of history, nor is he interested in passing judgment. Rather, he closely observes the ways in which love, death, war and nature act upon human beings. The story of "The New World" (and for that matter, of the New World) is a fundamentally Hegelian one; initial beliefs lead to their opposite, then to new beliefs that combine but transcend both. Even the love affair between Smith and Pocahontas, sensual and passionate as it is, can be understood in terms of thesis, antithesis and synthesis. For Malick, reality is cognitive, and thus ever-evolving, changing whenever it comes into contact with something new. So, for that matter, is filmmaking. While the version that will be released in New York and L.A. clocks in at 2 hours and 29 minutes, the wide-release version may yet be cut by 20 minutes. When Captain Smith finally returns to Jamestown from his idyllic sojourn among the Powhatan, he finds a lawless settlement turned startlingly feral and primitive by hunger and disease. Powhatan has instructed Smith to tell the settlers to leave, but they have planted corn in his absence, having earlier been given seed by Pocahontas. As they show no sign of departing, Powhatan orders an attack. Pocahontas betrays her tribe by warning Smith, and she is banished by her father and sold to the settlers as insurance against future onslaughts. Among them, she is slowly transformed into an Englishwoman, corseted, heeled and attended by a maid. Smith, meanwhile, is called back to England and tells a friend to tell her he has died. Pocahontas is overcome by grief and retreats into herself.

As the settlement grows, a new arrival, John Rolfe (Christian Bale), takes an interest in her and asks her to help him cultivate tobacco on his farm. Rolfe falls in love with her and asks her to marry him, which the princess agrees to do. She does not immediately love him, however, and the scenes between them are halting and tender. After the birth of her son with Rolfe, Pocahontas learns that Smith is alive, and on a trip to England, where she is received and feted by the king and queen, Rolfe arranges for them to meet. Kilcher, Farrell and Bale are masterful in difficult, nearly nonverbal roles. The courtship scenes of Pocahontas and Smith, lyrical montages that must have been particularly challenging, are profoundly affecting, and Bale likewise is wonderful as the patient, understanding Rolfe, who risks losing his wife to provide her with the chance to choose between them.

The scenes in England are as astonishing as the scenes in Virginia. An ambassador sent by Chief Powhatan to learn more about the English intentions and "meet this God they're always talking about," tours the sculptured gardens and topiaries of the royal court, marveling at the symmetrical trees and terraced gardens. Everywhere are straight lines and confined forms. It's a geometric world, where nature has been conquered and cultivated, representing the inverse and opposite end-point of a civilization, which seen through the eyes of the Powhatan ambassador looks startlingly strange and new. Like the creaky ships slowly shuttling the characters back and forth across the Atlantic, "The New World" is a work of breathtaking imagination, less a movie than a mode of transport, and in every sense a masterpiece.

From the NY Times:

December 23, 2005

MOVIE REVIEW | 'THE NEW WORLD'

When Virginia Was Eden, and Other Tales of History

By MANOHLA DARGIS

Toward the end of Terrence Malick's elegiac film, "The New World," the young Indian princess known as Pocahontas -- the "delight and darling" of her father, the king of the Powhatans of coastal Virginia -- pauses in front of a gilt cage containing a live skunk. Brought from the New World to the Old in 1616, this morose creature, curled as tight as a fist, is being presented to the English court alongside a bald eagle, an Indian priest and Pocahontas herself. The princess, dressed in Jacobean costume, a ruff collar fluting around her throat, and played by the sublimely lovely newcomer Q'orianka Kilcher, looks both at ease and entirely foreign. When she sees this pitiful captive, does she see any part of herself?

If that question is never answered in "The New World," it is because Mr. Malick, who wrote and directed the film, his fourth in three decades, never presumes to know the answer. For the filmmaker, who is more poet than historian, Pocahontas is clearly a metaphor (virgin land, as it were), but to see her as exclusively metaphor would only repeat history's error. What interests Mr. Malick is how and why enlightened free men, when presented with new realms of possibility, decided to remake this world in their own image: free men like Capt. John Smith (Colin Farrell), who marvels at the beauty of a place where "the blessings of the earth are bestowed on all" while Indians lie bound in his boat, and who claims to love, only to destroy.

Smith, whose histories provide much of what is known about Pocahontas, was part of a contingent of some 100 men charged with founding an American colony on behalf of the London-based Virginia Company. In April 1607, three of the company's ships dropped anchor off the Virginia coast and a group ventured ashore. What they found, one of the actual settlers wrote in a near-swoon, were "faire meddowes and goodly tall Trees, with such Fresh-waters running through the woods as I was almost ravished at the sight thereof." The colonists had entered a paradise, but they were looking for gold and a river route to the South Seas, not meadows and trees. They found Indians, too, though in Mr. Malick's description of this mutual encounter, it was not a happy discovery for either party.

The filmmaker opens "The New World" with images of rippling water, swimmers shot from beneath and the woman we will soon come to know as Pocahontas as she utters what sounds like a prayer ("sing the song of a land"). After a brief credit sequence, James Horner's score gives way to chirping birds, blowing wind and what might be the rumble of distant thunder or a cannon blast. This cacophony then melts into the opening notes of the prelude to Wagner's "Das Rheingold," the first opera in "Der Ring des Nibelungen." A haunting drone meant to suggest the rippling of the Rhine River, the prelude begins as a whisper that grows progressively louder until it reaches a crescendo, signaling the moment when the Rhinemaidens realize that the Nibelung dwarf Alberich has forsworn love for gold and power.

The musical chords ripple with escalating intensity as Indians run along the shore, excitedly pointing at the three ships. With a restless, searching camera that finds realms of beauty in a single leaf and the downy hair on a woman's forearm, Mr. Malick gives us a palpable sense of what this unspoiled place must have looked like to the English, what was found and soon would be lost. Like Smith, we come to this new world slowly, first in intoxicating glimpses, then in sweeping vistas. A soldier and an autodidact, Smith escaped captivity in Turkey and was said to have read Machiavelli; Mr. Farrell's captain doesn't look like much of a reader (or a greedy dwarf), but he does look like trouble.

Soon after they land, the colonists shut themselves in a fort and raise a towering cross. Smith, meanwhile, charged with finding fresh supplies, is imprisoned by Indians, brought before Pocahontas's father (called Powhatan and played by August Schellenberg) and either almost killed or just seriously frightened. The story of Smith's brush with death, which may have instead been an initiation ritual, remains under dispute. Mr. Malick stages the scene like a hallucination, a freak-out with shadows and smoke. Smith wrote that Pocahontas, then between 10 and 12 -- though here she looks dangerously older -- begged her father to spare the colonist's life. The purported rescue inspired myths about a romance, which in turn fed lurid fantasies about natives and the forces of civilization and helped fuel justifications for the domination of a land and its people.

In a gutsy move, the filmmaker represents this romance between Pocahontas and Smith as real, but only to flip it on its head. In quiet, drifting scenes set amid surreally beautiful wilds (the Virginia locations are paradisiacal) the two slowly circle each other like dancers, their respective interior monologues filling in the silence between them. In the past, Mr. Malick's fondness for voice-over has sometimes seemed like a crutch, symptomatic of a weak screenplay, as in his last film, "The Thin Red Line," or as a misplaced bid at naïve consciousness. Here, though, you feel as if you are eavesdropping inside the characters' heads. While Pocahontas's voice-overs are filled with schoolgirlish yearning, Smith sounds dangerously lofty, as if he is rehearsing the dissembling that will shape his later histories.

If the affair seems strangely ethereal, as if it were taking place in another dimension, in a lovelier, more enchanted realm, it is because Mr. Malick is fashioning a countermythology in "The New World," one to replace, or at least challenge, a mythology already in place. In Mr. Malick's interpretation, Pocahontas is no longer the simple girl of Smith's fanciful imaginings or the acquiescent native who bows to take the English yoke, thereby making way for all the colonies to come and all the catastrophes perpetuated against native peoples. Pocahontas is still irrefutably "other"; for a filmmaker living 400 years later in another world and different skin, there is no alternative. He is still putting words into her mouth, but with scrupulous tenderness.

The story of Pocahontas has inspired poems and portraits, histories and biographies and a 1995 Disney animated feature in which the cartoon princess wears what looks like a very full C-cup. "Captain Smith and Pocahontas," Peggy Lee sang, "had a very mad affair." Ripe for discovery and exploitation, she is uncharted territory and she has always sent temperatures rising. But Mr. Malick's Pocahontas, while impossibly young (the mature-looking Ms. Kilcher was 14 when the film was shot), is also the agent of her own destiny, never more so than after she and Smith are separated. The two are parted just as Mr. Farrell's moony reveries threaten to drown Pocahontas's voice. Once he is out of the picture, though, she secures her voice and then a husband (an excellent Christian Bale), and ushers the story toward its shattering close.

The real Pocahontas died in England in 1617, probably of tuberculosis or pneumonia, between the ages of 20 to 22, in the presence of her first or second husband. By then she was Lady Rebecca and had met Ben Jonson. At one time, her life may have been her own, but with her death that was no longer true. Like those Indian princesses who have long been a favorite of Hollywood, the pop Pocahontas who later emerged in song and cartoons is a comfortable fiction, at least for a country eager to tell its story in the best possible light. In that telling, Pocahontas is the noble savage exalted by an impulse to self-sacrifice for a white man. In Mr. Malick's telling, Pocahontas is a woman whose story has the reach of myth and the tragic dimension of life.

"The New World" is rated PG-13 (Parents strongly cautioned). There is some intense, bloodless violence and the beautiful underage lead actress may cause cardiac arrest among some viewers.

Origin of Innocence

The New World boldly reclaims the Pocahontas tale from Disney

By Luke Y. Thompson

Article Published Jan 26, 2006

America — and by extension Hollywood — has an obsession with innocence and the loss thereof. Every generation has that Moment When Everything Changed, from Pearl Harbor to JFK's assassination to 9/11. The impact takes awhile to settle in, then people forget again, and future generations are similarly traumatized. But if you really want to talk about clashes of civilizations and culture shocks, why not go back all the way, to the founding of the country as we know it?

Though Indians and white men had encountered one another prior to the Pocahontas tale that's retold in The New World, there was still innocence to lose, and that's the core of Terrence Malick's movie. You probably already know the basics, as told by Disney: Young Native American princess Pocahontas (played by newcomer Q'Orianka Kilcher) falls for handsome English explorer John Smith (Colin Farrell, who sounds way more Irish than English), eventually becomes "civilized," and visits the royal court in London. History isn't clear on the specifics, mainly because the principal accounts of the story were told by John Smith himself, years after the fact, and were likely exaggerated to make himself look better. Malick seems to be primarily following the Powhatan tribe's version of events, combined with some elements of Smith's accounts.

Facts and plot points are somewhat irrelevant to Malick anyway; he makes tone poems rather than narrative films. Long takes that drift through streams and forests, voice-over inner monologues from multiple characters, and people who show up without explanation or backstory are his stock-in-trade, but unlike his nigh-incoherent Thin Red Line, this movie isn't choppy or scattershot in its focus. For one thing, there are only three main characters, one of whom — Christian Bale's John Rolfe — doesn't even enter the story until the third act.

All of this might sound daunting, and it is, a little. You know how people occasionally come out of epic movies like Malcolm X and The Return of the King saying, "Wow, that didn't seem like three hours at all"? That won't be the case here — The New World feels every bit of its two hours and fifteen minutes (already shortened about fifteen minutes from its original cut). It doesn't feel like time wasted though. Everything is a visual feast, comparable in spectacle and wonder to any of the CGI fests we've seen in the past year. (It's all the more impressive if you can appreciate how cool it is that most of the film was shot using natural light.)

At the heart of it all is an entrancing lead performance by the teenage Kilcher, whose only previous movie role was as an extra in Dr. Seuss' How the Grinch Stole Christmas. Playing the young girl known as Pocahontas (a name never spoken aloud here), and the Anglicized woman christened Rebecca whom she eventually becomes, Kilcher embodies both free spirit and repressed soul, as the story commands. When she meets her inevitable fate, it feels like King Kong in reverse, with hairy man-beast Smith unintentionally luring beauty from the savage jungle, toward a world in which she can no longer be herself and where she is exhibited as an exotic sideshow. It wasn't the Puritans — it was beast that killed the beauty.

Whether or not Pocahontas and John Smith were actually romantic is still a matter of some debate, though it has become the stuff of folklore. She was around twelve years old when they first met, though in 1607 her age would not have been any kind of barrier. It may be a problem for some viewers, however, knowing Kilcher is in her midteens and Farrell about twice that. There's no sex, but everything short of it is implied. Still the overall feeling one gets is not one of leering in the vein of those people who obnoxiously lust after Emma Watson in the Harry Potter movies. With Kilcher's Pocahontas, the attraction is as much of the spirit as it is of her beauty, which is important, because her looks do not fade when strapped into a corset, though the inner light certainly does.

Oh, and let us all rejoice that we can watch this tale told without that fucking "Colors of the Wind" song. Someone needed to take the story back from Disney, and we couldn't have asked for more than Malick.

The bad

Movie Review: Terrence Malick's "The New World" (2005)

Cast: Colin Farrell, Christian Bale | Directed by: Terrence Malick

Opening Nationwide 12/25/05 — As the politically correct say, America is a new world only to the Europeans who exploited its human and other resources. This film shows how the white men were at first greeted with flowers (like Americans in Iraq) but later turned against the upstarts (like Iraq to Americans). Harvey Karten says: This pic is slow as molasses climbing up a tree in January. PG-13 for some intense battle sequences.

THE NEW WORLD

Reviewed by Harvey S. Karten

New Line Cinema

Grade: B

Directed by: Terrence Malick

Written by: Terrence Malick

Cast: Christian Bale, Ben Chaplin, Colin Cox, Colin Farrell, Christopher Plummer

Tourists who take in the sights of our nation's capital often drive farther south to Williamsburg, Virginia to take in the panorama of performers dressed in Colonial American costumes, working at sewing machines or baking or whatever else people did long before they opted to spend eight hours a day in front of the TV. Those who find the experience enlightening, if short on excitement, might be part of a target audience of Terrence Malick's new film, "The New World," which re-imagines one of the better-known romances of bygone times. The central focus of "The New World" is the love that bound two people of different cultures, one of the most written-about tales of interracial harmony to grace the U.S. history books until "West Side Story." Every schoolchild used to know that John Smith, about to have his brains dashed by rocks in a traditional ceremony by an Indian tribe, was saved at the last moment when Pocahontas, one of of the tribal leader's one hundred offspring, placed her head above Smith's thereby deterring the execution. Since these Indians left no written history, we'll have to trust the papers of Mr. Smith to the veracity of this melodramatic turn.

Early Seventeenth Century America has not been the most pressing subject for treatment by American film-makers, but it's close to ideal for director Malick, whose 1973 pic "Badlands–inspired by the Starkweather-Fugate killing spree in the 1950's—is moody and, more important, does not patronize the "barbarians" as you might expect from a more mainstream movie. Criticized by some for being painterly rather than Hollywood-cinematic, Malick indulges himself and those in his fan base who prefer leisurely (read: slooooooow) re-creations of events, whether based on an infamous crime spree or the conflicts and misunderstandings that took place in early Virginia between Native Americans and English aristocrats. New Line's "The New World" might just be the slowest-pace film of the year, which will probably deter those who might prefer that studio's "The Man," "Just Friends," and the upcoming "Running Scared" but will be welcomed by a sophisticated audience prepared to steep themselves in this period piece.

Leisurely though it may be, "The New World" is told in a conventional way–no flashbacks, no dream sequences–a story that not only has narrative cohesion but could be divided into two periods. The major segment gets us into the year 1607, when three English vessels sent by King James to Virginia to search for gold, culminating in the romantic attachment between John Smith and Pocahontas. The latter part finds its romantic center in the relationship between Pocahontas and John Rolfe, a liaison that would not have taken place had the Native American realized that her loved one was still alive.

The title of the film is an ironic one. America was "new" only when looked at through the eyes of Europeans and the mostly white settlers who set up homesteads far from their European roots. To the Indians, who for the most part left no written records, it was home for centuries, perhaps millennia. The America of the early Seventeenth Century traded TV's and computers for water suitable for bottling by Perrier; home-grown corn for McDonald's, and smog-filled black lungs for crisp, clean air. As sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists and historians tell us, there is no reason to believe people from pre-industrial societies were any less happy than those with modern conveniences, though the contrary might be true. The tribe pictured by Malick have painted faces that not even Bloomingdale's could match, wore loose-fitting garments rather than suffocating garters and laces, and bare feet or moccasins in place of boots with high heels.

When the explorers first arrived, the Indians, having never seen white men before, grimaced as they approached the sailing party, sniffing them like dogs who did not appreciate the odor of human beings who had not bathed in months. Though John Smith (Colin Farrell), a rebellious twenty-seven year old among the one hundred three aboard, was sentenced to hang for mutiny, Capt. Christopher Newport (Christopher Plummer) pardons him, realizing that every hand was needed to tame this strange new world. After a misunderstanding all but Smith were killed by the Powhatan tribesmen. That Pocahontas (Q'Orianka Kilcher) saved the handsome man is the part of the story that many recall today. Pocahontas's dad, Powhatan (August Schellenberg), had one hundred children with twelve wives (no time for TV anyway), and Pocahontas was his favorite. At the time of their meeting, Pocahontas was scarcely into her teen years, eager to learn the language and ways of these strange people. In no time, she is speaking complete English sentences, instructing her man in the customs of her people. When the Indians realize that the settlers who had returned to the Jamestown colonies were overextending their hospitality, war broke out, leading to Powhatan's banishment of his daughter for advising Smith of the coming battle.

The final third, embracing the liaison between Pocahontas and Captain John Rolfe (Christian Bale), is anti-climactic story-wise but rich in photography, costumes, and pomp–as Powhatan's daughter is introduced to the king and queen of England. Though near the final frame Pocahontas, who has been renamed Rebecca, revels in the cobblestone streets and long acreages of grass, she cares not that she remains an outsider to this Western civilization. Still, this segment, like the rest of the film, is rich in totemic camera shots–the tall trees, the flowing water, the resonant imagery. Soaring music fills the soundtrack, juxtaposed by periods of silence that a radio station would censure as dead air but which feed into Malick's artistic vision. There are pauses that would bring a jealous grimace to a playwright like Harold Pinter, monologues that might find a better home on the stages of sophisticated auditoriums like the Manhattan Theatre Club. "The New World" often comes across as indulgent and artsy, but Malick would not have it any other way. This is what will be cheered by a relatively small, but educated and curious contingent of ticket buyers.

Rated R. 150 minutes © 2005 by Harvey Karten. Member: NY Film Critics Online

On the Far Horizon, 'The New World' Slowly Emerges

By Stephen Hunter

Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, January 20, 2006; C01

Look at the savages! What beasts! Snarly, smelly, infested with fleas and lice, their skins marred by hideous markings, their visages warlike, their language a strange clottage of war whoops and gurgles.

And those are the British!

That's the initial point of view in Terrence Malick's "The New World," an attempt to rescue the founding of Jamestown and the myth of Capt. John Smith and Pocahontas in 1607 from the swamp of kitsch into which it has sunk. But at first it seems almost like something that might be named "Bambi vs. the Flying Saucers" set in a tidewater theme park called Benevolent Nature, with the forest creatures — graceful, beautiful, magical — contemplating the clanking, stumbling invaders who've beamed down from Olde Englande courtesy of strangely festooned motherships abob on the estuaries of the Chesapeake.

Malick almost has some fun chronicling this first encounter of the close kind. The Native Americans are at first amused by the outsiders: They've never seen so much hair, smelled such vile vapors (the boys have been cramped into a vessel little bigger than a Volvo for about eight months) and can make no sense of metal helmets, swords, high-heeled shoes and, most of all, white faces. They're like curious fawns, touching and giggling.

But soon it dawns on them that the furry boys and their prim, pale womenfolk mean to stay. That's evident as Jamestown itself arises and in no short period of time has come to replicate the glories of a Liverpool slum, complete to slatternly, ill-built buildings, puddles of fetid water, mud, pigs, chickens, scraps of junk wood and a surrealist agriculture dedicated to exotic, doomed grains.

And then that contagion of human socialization intrudes, the contagion of politics. Malick cuts quickly between the various factions on each side of the Lincoln Log fence the settlers erect: In the Powhatan councils it is debated whether to kill or ignore the intruders; in the English, it is debated whether to kill or ignore the Indians.

Gradually, personalities emerge. Rima the Bird Girl there, the barefoot Indian lass with Suzy Parker's delicate toes pedicured cute as baby bunnies, she's Pocahontas. That particularly gnarly brute, hairy as a bear and smelly as an outhouse in July, that's John Smith. The actors are Peruvian Indian-Swiss teenager Q'orianka Kilcher and Irish heartthrob Colin Farrell. Each looks the part: She's dark, swift, beautiful, and he's got the strength and thews of a man who was a mercenary and had seen combat all over Europe and the Middle East. Is it love at first sight?

Well . . . hard to say. It's something at first sight, but why should we be hasty when the director is never hasty. That's because Malick is of the introspective sort. He's the only man in history who could make a boring movie about the battle of Guadalcanal ("The Thin Red Line") and turn a Charles Starkweather-like mad dog's kill spree into a philosophic inquiry ("Badlands.") Here his distance from emotional engagement keeps the players far away, as if through the wrong lens of a telescope; thus it's hard to feel much for them or their turmoil, if it's turmoil at all they're feeling.

It's certainly not lust: The movie is almost sexless, and the play between the two romantic leads (and later with a third cast member, Christian Bale, as Pochahontas's eventual hubbie, John Rolfe) is all frisky necking and snuggling. It has a kind of 18th-century innocence, almost like Fragonard's "The Swing," the 1767 painting that encapsulates romantic purity. (Frankly, I much preferred the scalawag-horndog John Smith of John Barth's fabulous novel of that time and place and the devil plant tobacco, "The Sot-Weed Factor.")

Malick is far more interested in states of nature, which he expresses with extremely slow camera movement that notes with stunning precision how nature arranges bushes as opposed to how man arranges bushes. Really, is it that big a deal? Especially, when it turns out he favors nature over man. You see this choice running through the film. The forests of Tidewater country are lush, enchanting, inviting; in England, they've been reduced to mazes, cruelly cut into box hedges, perverted into something monstrous and different. It's so easy .

Likewise the buildings of the two races: The interior of a tribal lodge is filmed as if it's a cathedral bathed in radiant light through a stained-glass window, while the interior of the English hutches at Jamestown are threadbare, not merely decoratively but by metaphorical extension, spiritually impoverished. Again: easy .

The surprise — and the discordance — arises from the disconnect between the design of the film and the design of the characters. He could have settled for easy demonics of the Kevin Costner school: Indians saintly, whites monstrous. The artist in him — or possibly the adult in him — knows it's never that simple, and fortunately the actors are adept enough to suggest, however wispily, some ambiguities of character. Colin Farrell even makes you forget that he is Colin Farrell.

Thus the movie's more interesting drama is the nuances of personality in the mesh of myth. It's all here, all the highlights of the Pocahontas magical mystery tour: how she intercedes to keep the captain's head from getting pulped by boys who look like refugees from a Goth band; how the two — he's in his thirties, she's 13 (the actress is 15) — fall in love and communicate; how, in winter's icy grip, she leads her people on a relief mission out of sympathy for the starving white hairy ones; how she hides corn kernels by which the settlers finally learn to tease a life from the earth; how she is banished by her father, then kidnapped by the whites, then falls in love and marries the Englishman Rolfe (for whom we may issue thanks, as he first domesticated for home use the sot weed of the Barth book, thus sparing so many of us of a boring old age); and how, finally, she goes off to England to meet the king.

It was here that it dawned on me, and it will dawn on you, that the thing was actually conceived of as a romantic triangle. In Merry Olde Englande, she settles into a country squiress's life and soon bears the country squire a boy child. But then the thunderingly romantic, dark, hairy soldier/explorer/writer/tattooed bad boy returns. Will she stay or will she go? Oh, that's what this movie is about. Why didn't you say so earlier?

There are other annoyances. Like every movie Malick has ever made — not that he's made that many, having taken a 20-year vacation between "Badlands" and "The Thin Red Line" — this one was edited way down from a longer version. That's beginning to feel like a self-inflicted pattern: It lets him take credit for what might have been but not responsibility for what is. In this case, even in the past few weeks 16 minutes have come out of the initial version screened for critics (it still moves too slowly). And the original cast announcement (available on the Internet Movie Database) lists a variety of prominent performers — Jonathan Pryce, Noah Taylor and Ben Chaplin — who are now nowhere to be seen. Two great Native American actors — Wes Studi and August Schellenberg — are visible but almost without lines. And that might explain another silliness: The movie has a bloody battle sequence in which it appears that dozens of the already short-handed colonists are killed, but after the fighting, the same number of Englishmen and Indians are running about.

"The New World" is stately almost to the point of being static and thus has trouble finding a central story around which to arrange itself; it's not quite the thin dead line, but it's close.

The New World (135 minutes, at area theaters) is rated PG-13 for sexual suggestion and violence.

© 2006 The Washington Post Company

As the 'World' turns

Romance is the order of the day in Terrence Malick's now shortened epic

By David Elliott

UNION-TRIBUNE MOVIE CRITIC

January 20, 2006

A Terrence Malick movie – only four features in 33 years – is such a visual splurge that you feel the film and its coffee-table book have arrived in unison.

It therefore seems rather silly that "The New World" has lost nearly 16 minutes (tiny cuts done by Malick, at studio request) since a 2½-hour version opened in some cities late last year. Moody expansiveness is the Malick approach, and shrinkage is not his manner (count on the fuller version in a future DVD).

With cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, Malick colonizes virginal Virginia in 1607, as English intruders (all male) grab a patch of swampy shore near the vast forest. We feel the awe that F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote about toward the end of "The Great Gatsby": "For a transitory, enchanted moment, man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent . . . face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder."

The Brits call the natives "naturals," and the resident tribe is brutal in war but otherwise peaceful. And warily welcoming, even though the most alert brave (Wes Studi) mutters about what these odd interlopers might want next. The Indians often wear bold swipes of body paint and tend to move like springy, Arcadian dancers.

They have a lovely princess, Pocahontas. Q'Orianka Kilcher, who is of Peruvian blood, plays Pocahontas. Her sculptural face and soft, non-actress voice are not very expressive, but she flits through woods as if she can commune with forest creatures (her Indian speech is subtitled, but love gives her rapid access to English).

The main Englishman, John Smith (Colin Farrell), loves her mightily. Malick shyly poses their romance as a series of furtive, private encounters. Sex is only suggested (Malick loves sublimation), and the chief's daughter is seen as a traitor only after she brings corn seeds and food to the starving English in winter.

Malick finds a lot of wiggle room in known history. Filmed like a fluently unfolding frieze, "The New World" has natives like ancestral, Greenpeace warriors, while the whites are mostly freebooters and naval trash, ripe to turn ugly once they return to England. Looking for gold, they churn up mud.

The English suffer malnutrition and sickness; the coming holocaust of all the American cultures by imported disease is scarcely hinted. The Indians are mostly beautiful and, given their limited gene pool, appear in a remarkable spectrum of skin tones.

Smith, sort of a rebel spirit himself, shares in Pocahontas' poetic merger with the land. He is tranced. Their soulful bond nags at him once duty calls him back to the fort and his creepy compatriots. It is the era of Shakespeare, and the lovers are a less verbal Romeo and Juliet, caught between tribes that lack Shakespearean eloquence.

In picture-book terms, the film is touching. The visionary vistas, the call of birds, the girl's delicate delight in first love, the lissome Indian movements create a morning-in-America aura, but Farrell and Kilcher do not give the characters much more than symbolic personalities.

Malick builds capably to the fateful climax, the rupture of cultures, then glides on past it. As the whites take over, Smith exits, and a new lover is found for Pocahontas.

Like a balm for our abraded conscience, Christian Bale is her mannerly new man. We see England and its pretty Tudor court, in a surplus with stunning moments. Studi, like a forerunner of the last of the Mohicans, goes on the voyage to "count the Englishmen," and, wandering in teeming streets and a Kubrick-like formal garden, realizes he's found another world beyond counting or consolation.

Because it touches the almost magical dawn of our nation, and is shot with such luster and gravity (composer James Horner dipped into the classics), "The New World" tends to overawe. Painfully bittersweet nostalgia plucks nerves of cultural guilt, but you cannot fairly represent the fate of a hemisphere with hopeless lovers who seem both totems and tokens.

From the Rochester City News:

JANUARY 25, 2006

Uttering innermost thoughts without saying a word

BY GEORGE GRELLA

The remote, reclusive Terrence Malick occupies a most unusual position in American cinema as a kind of living anachronism, an artist practicing in a complicated, highly collaborative, labor intensive medium who behaves like some solitary, tormented genius from an earlier time.

After making two highly praised films, Badlands(1973) and Days of Heaven (1978), he lapsed into two decades of silence, finally bringing out the eagerly anticipated Thin Red Line in 1998. In that movie he turned James Jones's gritty short novel about a World War II battle for a Pacific Island into a dreamy Emersonian meditation on nature, innocence, and war, filled with shots of tall grass waving in the wind, rain sweeping in sheets through trees, close-ups of drops of water flowing down ferns, all accompanied by a voiceover commentary laden with the sort of ponderous sentimentality many people mistake for poetic utterance.

His latest work, The New World, unfortunately continues the style and theme of The Thin Red Line, employing the dubious legend of John Smith and Pocahantas to explore once again the contrast between unspoiled nature and corrupt civilization. Malick shows some of the history of the Jamestown colony, the first permanent European settlement in North America, beginning with the arrival of three English ships in 1607 and ending with the death of Pocahantas 10 years later.

He concentrates most of his efforts, naturally, on the relationship between the Indian maiden and the English soldier of fortune, which he depicts as the sort of Edenic idyll that Rousseau and his followers would celebrate a century later.

Apparently concerned with historical accuracy, the director works with natural light and actual locations, duplicating the clothing, tools, and weapons of the early 17th century, and featuring genuine Native Americans playing their ancestors, trained to speak the extinct Algonquin language of the tribe that the English encountered. Typically, he spends much of the film's time dwelling on the purely visual interpretation of his subjects, sweeping his camera through the forests and meadows, shooting at low levels to suggest the movement of people through the wilderness, using a mixture of hand-held cameras and slow motion to impart a weird tension and grace to his battle scenes.

His perfectly commendable emphasis on the visual unfortunately here tends to overpower everything else in the picture, so that he repeats endless scenes of landscapes or shows John Smith (Colin Farrell) and Pocahantas (Q'oriankaKilcher) gazing soulfully into each other's eyes or dancing around in fields for what seems like hours. What the film lacks in dialogue, however, it makes up for in the curious interior monologues he used in The Thin Red Line. The characters speak little to each other, but a great deal to themselves and the audience, almost as if they were delivering soliloquies, uttering their innermost thoughts, many of them of them once again of the moony pseudopoetic variety, without really saying a word, a device that Malick has just about finished off by now.

Although the director apparently indulged himself and no doubt enjoyed the whole process, the actors appear quite uncomfortable most of the time. Even while singing the praises of the noble savages and the Indian way of life —- and sounding very like Kevin Costner in Dances With Wolves —- Colin Farrell looks tense and uneasy, as if he comprehended not at all the point of his character or the story. The newcomer Q'oriankaKilcher, allegedly beautiful and lively, overacts and poses obnoxiously and, strangely, acquires an upper-class British accent in a very short time after meeting John Smith.

Notorious for delays and last-minute alterations —- the movie was supposed to appear in November, for example —- Malick here appears to have edited with an axe, cutting out whole lines of plot that he then papers over with cryptic, artificial exposition. He repeats so many sentimental shots of the lovers and so many phrases of the portentous interior monologues that the long, slow film seems even longer and slower than its actual two hours.

Despite the promise of its subject and the artistry of its director, The New World, finally, is cruelly, punishingly dull, a sort of purgatorial experience that forces the viewer into melancholy contemplation of matters like death and disaster, recollecting all his misdeeds and regrets, penitently enumerating his countless sins, and hoping for some forgiveness.

Leaving the theater, as a result, provides a truly blessed relief.

The New World(PG-13), written and directed by Terrence Malick, is playing at Little Theatres and PittsfordPlaza.

The ugly

Not much new in 'The New World'

Posted: January 11, 2006

by: Jennifer Hemmingsen / Indian Country Today

LOS ANGELES -- There are a lot of reasons not to like Terrence Malick's new movie, "The New World." The melodrama is thick, the internal monologues are endless and the soap operatic overuse of the thousand-yard stare is absolutely maddening.

But probably the best reason is this: The story is tired.

In this latest version of the founding of Jamestown, Malick spins the same tale about the explorer and the explored that white men have been hawking since Shakespeare: he's just dressed it up with historically accurate props.

The production crew says "The New World" is not a history, but a fictional love story between Captain John Smith and Matoaka, aka Pocahontas, daughter of Powhatan, the powerful chief of the Powhatan Confederacy of Tidewater Algonquian tribes. But it's not really a love story, either. With Smith playing the colonizer and Pocahontas the "good Indian," it's actually a metaphor reinforcing the tragic inevitability of the conquering of America -- a story we've heard too often already.

The film opens with a voiceover of Pocahontas, played by then 14-year-old Q'orianka Kilcher, saying: "Come, spirit, help us sing the story of a land ..." as the camera captures shots of a pre-colonial paradise: grasses swaying in the breeze, happy Native people swimming in clear water. Then come the Englishmen -- dirty and sweaty, loutish and loud.

The Natives are fascinated. They jump. They point. They look at each other in awe. They approach these strange people, sniffing around and fingering their clothes. The Englishmen, on the other hand, seem nonplussed. They suffer the attention of the "naturals" until Smith (played by Colin Farrell) spies Pocahontas and falls instantly in love. He rubs his eyes. Is she a dream?

No, but she is a myth.

What little we know about Matoaka is pieced together from the historical accounts of others, especially Smith. The real Pocahontas was probably about 10 or 12 when she met the bedraggled colonists in 1607. They were camped on the disease-ridden lowlands near the James River. More than half of them died by the end of the first summer. More were murdered in periodic fighting with the Powhatans. Pocahontas visited the fort during the peaceful times, and Smith befriended her, likely because he knew the land's inhabitants were the key to his settlement's survival.

Whether or not Pocahontas actually saved Smith's life, or if it was ever in jeopardy, is much debated. But Pocahontas often served as ambassador between the two communities, bringing food to the starving colonists and, most controversially, letting them know of her father's plan to ambush the settlement and be rid of them once and for all. In return, the colonists kidnapped her. She converted to Christianity and married a tobacco farmer named John Rolfe, played in the movie by Christian Bale, who later paraded her around England with their infant son to woo potential investors. She died in her 20s, in England.

While the movie pays lip service to these life events, it never delves into Pocahontas' character. Her kidnapping, conversion and move to England are given a cursory nod. Her only real grief is for her lost lover, John Smith.

One of the few things historians agree on in this story is there was no romance between the two. So why is that star-crossed love the crux of this story?

"We chose to go with that powerful myth of this great love affair that couldn't be," said Producer Sarah Green.

"This wasn't about telling every bit of that history; this was about explaining love and the consequences of rash actions and letting that metaphor speak in a larger way about our country."

So how is this movie different than older versions like, say, the Disney epic?

"To be honest, I don't know that I've seen them," Green said. "I only know the story from grade school."

Not everyone is buying the metaphor.

"It's not my cup of tea," said Cherokee actor and activist Wes Studi, who plays Opechancanough in the film.

Studi, who is also a spokesman for the Indigenous Language Institute, said he got involved in the "The New World" because of the original script (the final cut of the movie is missing most of his character's development) and the historical research that went into it. The production team hired language expert Blair Rudes to research the indigenous language and use it for much of the film's Native dialogue. The resulting lexicon is being used by the Pamunkee tribe. Unfortunately, it wasn't much used by Hollywood.

"I'm a bit disappointed that so much of that reintroduced language wasn't used in the film," Studi said.

"A lot of my scenes are on the cutting room floor."

Studi said the original script went into much more detail about his character. By the time Malick was done cutting, it was hard to tell if Opechancanough is Pocahontas' brother or her boyfriend. Actually, he was her uncle, and a great leader who went on to lead a nearly successful charge against the colonists.

So what will it take to write a new story about the "new world"? A different director? Another 400 years?

"What it would take is for me to edit it," Studi said.

Introducing Q'Orianka Kilcher

In some ways, starring in a big-budget Hollywood movie hasn't changed Q'Orianka Kilcher's life. She still lives in a Santa Monica apartment with her mother and brothers. She still likes to go camping. But in other ways, the life of the 15-year-old star of Terrence Malick's new film "The New World" has changed dramatically.

"In a way, I feel like I've already lived an entire life," Kilcher said. "Playing Pocahontas was such an emotional roller coaster."

A home-schooled ninth-grader who enjoys history and making her own clothes, Kilcher has a talent for performance. Already, she has played a choir member in the 2000 release of "How the Grinch Stole Christmas." She's performed on television, placing second in the Young Singers category of "Star Search." She's even been known to turn out a mean Brazilian dance on the Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica.

But none of those roles has taken -- or given -- as much as her latest.

When Kilcher began rehearsing for her role, she started at square one.

"Like everyone, I just knew the cartoon," she said.

But as she learned more about the history of the famous Powhatan girl, and started acting out her struggles, she suffered along with her character.

"I was very emotionally raw," she said. "I would go home and sometimes cry for four or five hours straight."

Unfortunately, Kilcher said, many of those scenes -- where Pocahontas is grieving for her lost family and lover Capt. John Smith -- were cut from the final edition of the film. She hopes they'll reappear on the DVD release.

But the work did help Kilcher reconnect with her Native roots. Her father is a Quechua Indian from Peru. After filming, she traveled to South America to connect with her paternal relatives for the first time since she was a baby.

Now the actor, singer, dancer and teenager has a new dream. Once she's finished working on a CD she's made of original songs she wrote during the filming of "The New World," she wants to start a music school in her father's native country.

"To see my father's family, it filled a hole inside of me," she said.

RICHMOND, Va., Jan. 16 /PRNewswire/ — The film is a Hollywood rehashing of the Pocahontas myth, this time without Disney animation. That myth has been debunked by modern historians, who say that John Smith's account of Powhatan's daughter throwing herself across his body just as he was about to be killed could not have happened.

"This film isn't history," notes Karenne Wood (Monacan), Chair of the Virginia Council on Indians and a PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of Virginia. "It's harmful, because it portrays our people according to stereotypes about American Indians that we've worked for years to dispel. Our women appear as either princesses or squaws, and our men are either noble or warlike. The New World is old hat, to us. It's the same story, this time with Native actors and consultants. But it's still wrong."

Particularly offensive to Virginia Indian women is the characterization of Pocahontas as the object of Smith's physical desire, even though she was only 11 or 12 when they met, and Smith was closer to 30. The role is played by a 14-year-old actress. "As the mother of a teenage daughter, I was very uncomfortable with the romantic story line between Ms. Kilcher and Mr. Farrell," says Reeva Tilley (Rappahannock), Tribal Councilwoman. "Mr. Malick had the opportunity to make an epic film about the merging of two dynamic cultures and their contributions and survival in the New World, yet the main focus remained the mythical love affair between Pocahontas and Captain John Smith. This film does not portray the true traditional values that I want conveyed to the world about the Virginia Indian people."

Virginia Indian leaders are frustrated, too, by the film's release to promote the 400th anniversary of Jamestown. The Tribes in Virginia have never received the federal status enjoyed by some 567 other Indian tribes. Six of the Virginia Tribes want recognition to represent their culture at the Jamestown Anniversary. Chief Anne Richardson of the Rappahannock Tribe spoke briefly on the recognition issue. "I feel it will be an international embarrassment if Virginia celebrates the 400th anniversary of the establishment of the first permanent English settlement in America, and our government fails to recognize the Virginia Indian tribes that made it possible. The United Kingdom honors us as sovereign nations, but our own country does not. I think it speaks volumes about how our government really feels about us. Someone please inform the Congress that the war is over! How many generations will have to pass away before we can be honored in our own land?"

SOURCE Virginia Indian Tribal Alliance for Life

"New World" from a Native perspective

Movie review

Steve Cowley

2/1/2006

Dramatic histrionics aptly describes The New World, a new feature film written and directed by Terrence Malick that opened recently. Talk about a miscast and a movie that should never have been made. Malick should have passed on this one. Instead what he wrote is work better suited as a simple contemporary dance piece rather than a major motion picture. It would have had a better chance and made more creative sense.

The New World is a disjointed heap full of clichés and caricatures that appear to meander forever. And forever. The opening fifteen minutes is one of the most excruciating moments put to celluloid ever directed by anyone whose name isn't Michael Cimino. Its direction was amateurish and the cinematic tone was self-effacing -- but not in a way Malick most likely intended it to be. It was probably a fluke.

Bob Horner's usually exquisite music direction in the opening is simply wasted as the film opens with the ‘discovery' of a new world. Credit Malick for not going on and hiring the Highty Tighties Virginia Tech marching band for the opening.

An adventurous interpretation of controversial subject material already covered most recently by Disney and Malick was simply not up to it. A blaring omission that obviously comes to mind is for over two hours Pocahontas' name is not mentioned once. Love her or hate her, at the least Malick should have given the character her due. In Malick's film everyone calls her ‘Rebecca' played by newcomer Q'orianka Kilcher. So when Malick provides a little homage to Irene Bedard, the actress who played the Disney animated version, Bedard's scene is almost a flash. It didn't make sense. In this version Bedard plays Kilcher's mother. So leave the small ones at home or you will be explaining why for months.

Malick doesn't even try to be coy with his interpretation of Pocahontas' affair with Captain John Smith played by Colin Farrell. Pocahontas opens her heart to Smith and Jamestown and she literally saves them from starvation in a thanksgiving scene straight out of drama 101 class. Hallmark could sue Malick for license infringement on that one scene alone.

A saving grace for this cinematic wannabe is the beautiful cinematography by two-time Oscar Academy winner Emmanuel Lubezki. Magnificently capturing the sweeping vistas of the Virginian landscape, the vegetation, animal life and the marshlands, Lubezki expertly photographed scenes that made it appear fresh to the eyes. Almost like a new world.

American Indian actor, activist, entertainer, Wes Studi, is used as scenery in his role as Opechancanough. He is never defined and the dialogue he delivers is wooden. Studi recently stated in an interview with an American Indian news publication that he was concerned and disappointed at the final cut of the film. Was Wes more ticked about the cutting of his scenes or in Malick's direction? In his interview his comments were unclear.

Historically, the characters, including Kilcher's first lines, are spoken in the Algonquin Cree dialect. Nipi in Cree means water, and that is exactly what Kilcher interprets for Smith in their early scenes together. Canadian-born theatrical stage actor Billy Merasty playing Kiskiak seemingly knew the intent of Malick and simply delivered most of his lines in his native Cree language. Good for the noted and respected actor.

From an American Indian standpoint, that is the only good thing about the film. Some credit must be given to the dedication and hard work of casting director Rene Haynes. American Indians are working and acting so this fact should not be lost on the American Indian community. At the least American Indians are being hired to play American Indian roles. In Malick's film this altruism is too bad and too sad.

About the author: Steve Cowley, Cree from Manitoba, began his career as journalist in the early 90's in Canada. As a New Yorker since 1993, fresh out of the New York Film Academy, he worked at the American Indian Community House as the assistant to the Director of the Performing Arts Department and is currently the Employment Counselor in the WIA (Work Employment Act) Dept. He is the CEO of Tapwe Production Projects in NY and continues to write for the American Indian Community House's newsletter, the Flying Eagle Woman Fund's website and for the Tapwe web site. Read more about Steve and Tapwe Production Projects at www.tapwe.com.

More Native views of The New World

Virginia tribes protest "New World"

Malick's vision: trick or treat?

My review:

In his movie The New World, Terrence Malick depicts a romance that never happened. Can we excuse this invention even though Pocahontas was only a child at the time? Is it okay if the movie presents her affair with John Smith as a symbolic union between the Old and New Worlds?

Well, no. Suppose the romance did occur and Pocahontas was 15, like actress Q'orianka Kilcher, not 10 or 12. It still would have been an exploitative relationship, with an exotic and experienced soldier of fortune seducing an innocent young maiden. Today the law would deem it statutory rape or child molestation—not something you want to glorify.

The point is that the union is symbolic in more ways than one. Yes, it symbolizes the union of the Old and New Worlds. It also symbolizes what happens in a union of unequal partners. One lives and flourishes; the other withers and dies.

Despite The New World's good intentions, Indians have reason to be upset by it. The movie romanticizes their sad history, turning it into a love story with a happy ending. It closes with Pocahontas's son scampering in a garden Wonderland, as if the future is bright. His joy suggests that both sides will benefit from the clash of cultures.

In reality, Pocahontas naively helped the Europeans who ultimately killed her people. Like other "good Indians," she was a dupe or a pawn, not a heroine. When her father forbid her to aid the interlopers, he was acting wisely; when she disobeyed him, she was acting foolishly. The Indians would've been better off if they had let Jamestown's colonists die.

Americans are a little unclear on Pocahontas's role in history. A children's book titled American Heroes lists her because she's a "symbol of friendship and peace." Hello? The Statue of Liberty is a symbol of friendship and peace. So are Barney, the Teletubbies, and Hello Kitty. But that doesn't make them American heroes.

Critics have rhapsodized over Malick's poetic filmmaking, but The New World isn't that much different from Disney's Pocahontas. Both movies emphasize lush nature over deep characters. Both suffer because the storyline—Pocahontas loses John Smith, finds John Rolfe, then dies—is inherently unsatisfying. Yet both deserve accolades for their visual splendor.

So enjoy the films, but don't ignore the message of these fictional romances. When they promote Pocahontas from a child to a woman, they make her a co-conspirator in the Indians' eventual downfall. As James W. Loewen put it in his book Lies Across America: "Whites deserve the country, goes the implicit argument. Look—here are the good Indians who welcomed us to it and helped us take it."

Malick's noble savages

Other than the central romance, does The New World come across as an authentic take on Natives? For the most part, yes. Only a few things struck me as stereotypical.

The Indians have shaved heads, which may be historically accurate but is also a movie convention for denoting their strangeness. They paint themselves blue and white, a combination I've never seen in historical drawings that again suggests weirdness. Adding to the alien feeling is the shadowy spectacle in their hall of justice and the collection of Tiki-style idols.

The movie also idealizes these unnatural "naturals." They're gentle and loving, says the narrator, with no jealousy or sense of possession. Well, yes, if you ignore Chief Powhatan's conquest of the neighboring tribes, which created a confederacy with himself as the absolute monarch. And the Indians show off their buff bodies with revealing clothes—even in the dead of winter.

Perhaps the worst touch is Pocahontas's submissive words, which contribute to the sense of tragic destiny. "A god he seems to me," she says of John Smith. "I belong to you," she says to him, and "You flow through me like a river."

Instead imagine if she had said, "I saved your life, so you owe me," or "You're such a screw-up, I don't know why I bother with you." For all we know, she did say these things. The movie may have turned a bold, independent girl into a servile, smitten woman.

But should you see it?

Despite the negative tone of my commentaries on The New World, I enjoyed the movie. I agree with Luke Y. Thompson, who wrote, "Everything is a visual feast, comparable in spectacle and wonder to any of the CGI fests we've seen in the past year" (Miami New Times, 1/26/06). And with Kirk Honeycutt, who wrote, "As with all films in Malick's slim body of work, its imagery, haunting sounds and pastoral mood trump narrative" (Hollywood Reporter, 12/13/05).

Newcomer Q'orianka Kilcher deserves the Oscar speculation she got as well as the Trustee Award from the First Americans in the Arts. "Kilcher's girl/woman charm, poised naivete and intriguing unfamiliarity lend Pocahontas a considerable fascination," wrote Todd McCarthy (Variety, 12/12/05). But that's not to say the characters are fully realized. "In picture-book terms, the film is touching," wrote David Elliot, "but [Colin] Farrell and Kilcher do not give the characters much more than symbolic personalities" (San Diego Union-Tribune, 1/20/06).

The cinematography may have captured the earthy feel of an Indian village better than any previous Native-themed film. Usually this kind of story takes place in the wilderness, but here we spend a good half hour seeing how the Indians live. And the story presents the clash of cultures well. Two scenes stand out. One, at the beginning, "when the Indians, having never seen white men before, grimaced as they approached the sailing party, sniffing them like dogs who did not appreciate the odor of human beings who had not bathed in months" (Arizona Reporter, 12/22/05). The other, at the end, with "Opechancanough touching the skirts of huge shrubs trimmed into a bell shapes, while exploring a sculpted garden whose very existence testifies to the West's need to conquer (rather than coexist with) nature" (New York Press, Dec. 21-27, 2005).

To sum it up: "‘The New World' often comes across as indulgent and artsy, but Malick would not have it any other way. This is what will be cheered by a relatively small, but educated and curious contingent of ticket buyers" (Arizona Reporter, 12/22/05).

Rob's rating: 8.0 of 10.

Related links

Pocahontas bastardizes real people

Pocahontas II: flawed again

The best Indian movies

Readers respond

"I hate to say it, but I think you got some facts confused regarding John Smith."

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.