An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Voodoo Villain Hurts The Missing:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Voodoo Villain Hurts The Missing: An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Voodoo Villain Hurts The Missing:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Voodoo Villain Hurts The Missing:

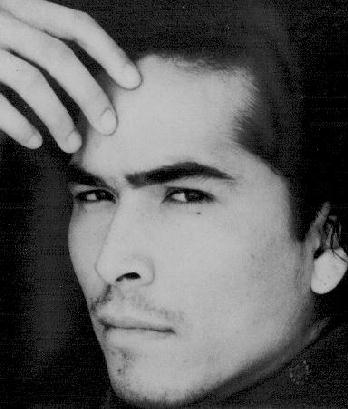

Ron Howard's new western presents an Indian villain straight out of the pages of pulp fiction. Eric Schweig's character, known as Pesh-Chidin, is one of the nastiest Natives ever to appear on-screen. You have to go back to Magua in The Last of the Mohicans (published in 1826) or Injun Joe in Tom Sawyer (published in 1876) to find Indians of comparable evil.

Liam Lacey's review in the Globe and Mail, 11/26/03, gives The Missing's premise:

Shot in classic widescreen, the film features a pair of broad-as-the-frontier performances by Cate Blanchett as a "healer" and Tommy Lee Jones as her estranged father who lives as an Indian, as they join on a quest to save a teenaged girl from an Apache kidnapper.

Sony's official movie site offers a more detailed synopsis:

The Missing, starring Tommy Lee Jones and Cate Blanchett, is a bone-chilling suspense thriller from Ron Howard and Brian Grazer, the Oscar-winning director-producer team of A Beautiful Mind.

The Missing is the story of Maggie Gilkeson (Cate Blanchett), a young woman raising her two daughters in an isolated and lawless wilderness. When her oldest daughter (Evan Rachel Wood) is kidnapped by a psychopathic killer with mystical powers (Eric Schweig), Maggie is forced to re-unite with her long estranged father (Jones) to rescue her. The killer and his brutal cult of desperados have kidnapped several other teenage girls, leaving a trail of death and horror across the desolate landscape of the American Southwest. Maggie and her father are in a race against time to catch up with the renegades and save her daughter, before they cross the Mexican border and disappear forever.

The Missing = The Searchers?

Lacey puts The Missing in historical context:

Though based on a novel, the movie is obviously derived from John Ford's hugely influential late 1956 western The Searchers, in which John Wayne plays an obsessive, native-hating Confederate veteran who travels on a five-year quest with his half-native nephew to track a Comanche chief who has kidnapped a teenaged girl from their family. The film, which has influenced everything from Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider to Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver to George Lucas's Star Wars, is a disturbing milestone in movie history: Homeric in sweep, it reveals a pathological racism underlying the western myth.

Howard's film, The Missing, shrinks in the former film's mighty shadow. It might better be titled The Awkward. It's an unlikely and often risible mixture of The Searchers with some disorienting touches of The Blair Witch Project thrown in.

As did many critics, Elvis Mitchell also compares The Missing to The Searchers in his review. From the NY Times, 11/26/03:

Apparently the only thing tougher than endurance on the frontier is sitting through a movie about endurance on the frontier — at least that is the point "The Missing" seems determined to make. Amazingly, what it also seems to be saying is that nearly 50 years after John Ford's "Searchers" we have arrived at a point in film history when the movie industry can offer a less sophisticated version of the same material.

The wicked witch of the West

Kenneth Turan provides a more-or-less neutral overview of Pesh-Chidin, the Apache brujo (witch), in his review. From the LA Times, 11/26/03:

No western is complete without a bad man, and one of the things that makes "The Missing" both effective and particularly modern is the nature of its villain. He's nameless in the film, though Samuel Jones refers to him by the Spanish "brujo" and the credits call him Pesh-Chidin, an Apache term that means the same thing: witch.

Today's audiences, aware of alternative forms of spirituality, will be more receptive to the presence of a Native American shaman, a powerful sorcerer capable of clouding men's minds. Convincingly played by a heavily made up Eric Schweig, the scarred and creepy brujo, whose murderous handiwork makes everyone who sees it, audiences included, squirm, is a disturbing, distinctive bad guy who proves to be very much a match for the forces of good.

More pointedly, Lacey tells some of The Missing's problems in depicting Natives:

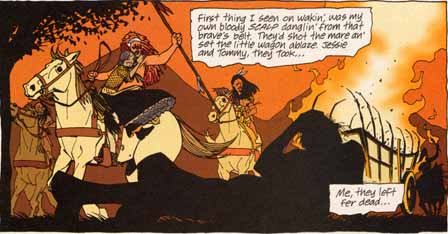

As Jones and Maggie strike out to rescue Lilly, they're accompanied by her spunky younger sister, and eventually a couple of good Indians who are happy to die for their cause. The self-consciousness of the script on racial issues borders on the embarrassing: White and native are both evil, the bad native is the evilest. The witch turns human bodies into giant bouillon cubes, uses a hairbrush to induce blistering fevers, blinds a travelling photographer and shoves sand in his victims' mouths.

Each time the supernatural elements are introduced, they undermine the movie's seriousness. There's a particularly awful moment when Jones, lying in the desert, looks up at a waiting vulture. Watching his stare, you have a horrible realization he is going to start communicating with it, like an early-days Carlos Castaneda.

One indication of Howard's relative squeamishness compared with Ford's: Wayne's character was ready to murder the girl, whom he viewed as sexually contaminated, "a Cheyenne buck's leavings." In Howard's movie, the bad Indian is not interested in rape, just evil magic and cash. This not only sanitizes the attack, but renders a scene where he rejects cash for the girls as nonsensical.

Another witchcraft-voodoo-kidnapper <sigh>

Another review explores the stereotyping further. From the Native Times, 11/27/03:

Another Movie Reinforces Unbeautiful Stereotypes

"Missing" presents Indians as VooDoo villians

TULSA OK

Michelle Gray 11/27/2003

Halleluiah! Indian people can feel grateful again for being defined by a Hollywood white guy who ought to know better. "The Missing," directed by Academy-Award winner Ron Howard ("A Beautiful Mind"), is based on an old western, "The Searchers."

The theme is familiar. In a dime-store western, the bad old Apache Indians stole a bunch of virginal white girls from their hard-working parents to sell them into prostitution for cash.

They're savage, they're gritty, they smell bad, and the leader, Chidin (Eric Schweig ["Last of the Mohicans," "Skins"]), has bad skin and hideous facial scars just in case you weren't sure he was bad. He blows some awful-bad powder on you that makes you squirt blood out of your eyes and then you die. If he's out of his nasty voodoo dust, he'll bludgeon you with his mallet faster than it takes him to blow his nose. And if he's too busy to do it himself, he'll scare his little Indian henchmen into doing the job for him. They apparently can't think for themselves, even though they are smarter and better looking.

But it isn't all bad. There are a couple of "good Indians." You know they are the good guys when they conveniently run in to Sam (Tommy Lee Jones) because they are dressed in white buckskins and don't have bad complexions. And they have brushed their hair recently. Obviously, too, they are the good Indians because they decide to risk their lives to help the white guy out.

.

.

.

It's unfortunate that the stereotypes are so blatant, and that Indian people are again reduced to freakish witch doctors with magic death potions and no impulse control, because the movie is well produced. Which is what makes stereotyping so harmful, it is often hidden in a good movie.

Eric Schweig is the most menacing and terrifying beast seen on two legs since we first met Hannibal the Cannibal. Schweig never lets up, and if you were being stalked by him, you might just give up and do yourself in just to avoid his wrath. This character makes it hard to remember him in his other roles, he is so convincingly evil.

.

.

.

If the Indian movie buff can take the bad with the good, then this film might be worth a shot. But for those who are tired of being objectified, and misunderstood this one might be better left to Western film fans. There are enough "Indian-witchcraft-voodoo-kidnapper" movies out there for producers of Ron Howard's caliber to consider spending money and resources on stories that better address Indian-white relations.

One of the problems with these types of movies is how other movie critics handle their reviews. Not the least of which is Dennis King of the Tulsa World, who in his biting review, describes Eric Schweig's character as a "psychotic Apache," and "…a snaggle-toothed, grimy Eric Schweig," calls Tommy Lee Jones' character a "taciturn white squaw-man." Whatever might he mean by that? It is apparent King does not know ‘squaw' is a deeply offensive term which is so vile this reviewer will not translate it so not to offend. He then expresses his disdain at what he perceives as an overly lengthy "Indian curse sequence." He finished his commentary by saying that this was a "respectful throwback to the good old days when cowboys were kings at the movies." Classy, Mr. King.

If I read the reviews right, the good Indians are Bible-quoting Christians while the evil ones practice a corrupt, probably false version of Apache religion. If true, The Missing furthers the commonly-held notion that Christianity is somehow loftier and nobler than Native religions, which are dark, impure, and prone to be used for immoral purposes.

The "white Indian" stereotype

Christine Olinger (aka "the movie muffin") dismisses one potential problem while raising another in her review for Reel Reviews:

So often when Hollywood makes movies about American Indians they either slander the culture in question or elevate it to something ridiculous. In this case we are dealing with Apache culture. A great deal of hurumphing has been sounded over the use of the word "witch" to refer to the seriously twisted, evil, creepy villain, played by Eric Schweig. The word only comes up once, and it's used by Tommy Lee Jones' character, Samuel Jones. The word would have been a completely natural usage for this era and setting, just as the generic, indiscriminate animosity toward any and all Indians was common. "Witch" is simply the term he uses to let others know that the man in question is bad, not a medicine man who he, as a person who honors the Apache, would respect.

Interestingly, the issue of Samuel Jones as the "adopted Indian" is ignored by critics and movie-goers. This myth of the white Indian is exactly that: a myth. White men may have become friends with Indians, some may even have lived either among them or close to them, but these infamous Hollywood white Indians are creatures of fiction. Dances With Wolves was loved by white critics. Indians refer to it as Dances with Bankers. The white Indian stereotype is much more exploitive than either the "witch" that is really an evil Indian who has apparent spiritual power or the stupid calvary who use [a] Chiricahua scout [as] the only able-bodied man in the group.

The point: Hollywood often uses white heroes in "ethnic" movies because it doesn't think ethnic heroes can carry a picture. Dances With Wolves is just one famous case. You can find examples throughout movie history: Jimmy Stewart in Broken Arrow, Tom Laughlin in Billy Jack, Val Kilmer in Thunderheart. The same applies to other exotic cultures: Tom Cruise's The Last Samurai has been called Dances With Wolves in Japan.

Perhaps unnecessarily, Olinger adds:

I have heard Ron Howard say he researched the cultures very carefully before making the film. It was not in any way evident on the screen.

Apaches disagree

Curiously, some Natives see The Missing in a different light. An Associated Press article explains how today's Mescalero Apaches view the movie's Apaches:

Tuesday, December 16, 2003

Apaches Savor Language Once 'Missing'

Ron Howard Film Spurs Hope That Mescalero Residents Will Retain Traditions, Despite Influence of Pop Culture

By RICHARD BENKE | Associated Press

Tommy Lee Jones speaking Apache? Word swept through the Mescalero reservation like an early winter wind.

Not only Jones but most characters in the Ron Howard film, The Missing, speak the Chiricahua dialect of Apache, and most adult Apaches in the audiences have said they could understand every word.

The children, who couldn't, suddenly wished they could.

That's what Mescalero Councilman Berle Kanseah and Chiricahua linguist Elbys Hugar intended as technical advisers for The Missing, a tough tale of 19th century frontier life starring Tommy Lee Jones and Cate Blanchett.

The 21st century — television, popular culture — is killing minority cultures, starting with language, Kanseah said.

"There's a generation gap that's growing," he said, suggesting Apaches aren't the only ones facing it. "We need to enforce the home and not lose our way of life, which is our language."

Hugar, a great-granddaughter of Cochise — who became principal chief of the Apaches in the late 1860s — addressed the cast before shooting. Co-star Jay Tavere, a White Mountain Apache, recalled: "This is the first thing that Elbys said to us: 'This is more than a movie — this is for the whole Apache nation.' "

It was the first film that any of them could remember in which Apache was spoken well enough on screen to be understood. Usually, Westerns were dubbed in Navajo, a related language, said supporting actor Steve Reevis, a Montana Blackfoot who has worked several films but never spoke Apache before The Missing.

The film is set in southwestern New Mexico in 1885, just as the last of the Apache conflict was ending. Jones' granddaughter — Blanchett's daughter — is abducted by a ragged band of Indians and whites who sell women into slavery in Mexico.

New Mexico college student and rodeo competitor Yolanda Nez, a Navajo, plays a captive who is Apache. Her father, Tavere, and Jones set out to keep the slavers from reaching Mexico.

The slavers are led by a brujo, a medicine man gone bad, played by Eric Schweig. Combat between Jones and Tavere and Schweig is inevitable.

The border slave trade is historically factual, producer Daniel Ostroff said.

University of New Mexico historian Paul Hutton, who also consulted on the film, concurred. "Indeed people were being kidnapped all the time," Hutton said Monday.

Apaches appreciate the film for showing them as they were — the good and the bad, family-oriented, generous, faithful to their religion and good-humored. The brujo played by Schweig is not intended to be Apache, though he speaks Apache, the producers say.

Many Apaches have gone back two and three times to see The Missing, Kanseah said. The producers gave a screening for 500 Mescalero students in Alamogordo last month, and the tribe has been busing students to theaters in nearby Ruidoso. Two more screenings were held here Sunday for hundreds more students from several tribes who attend Santa Fe Indian School and other tribal schools in the surrounding area.

"It made me feel proud," said Megan Crespin, 8, a third-grader from Santo Domingo School. Her tribal name is Moonlight.

Desiree Aguilar, 14, is a natural-born native speaker, fluent in Keres, the native tongue of Santo Domingo Pueblo. She watched the film with an analytical eye.

"It was very intense," the ninth-grader said. "It kept you wanting to watch it."

Kevin Aspaas, 8, a Navajo student, said he liked the hawk that led Tommy Lee Jones back to his family. "I really enjoyed it — it was a scary and cool movie," he said.

He planned to write a review of it for his class. He said he is learning Navajo and said a few words in his native tongue.

While the last screening played to the students, Kanseah, Nez and Tavere made some comparisons among Navajo and Apache dialects, all of which stem from the Athabaskan root language common to a number of North American tribes.

During the film, even Tommy Lee Jones' grasp of the language was understandable to Apaches and many Navajos. At one point, Jones says a well-known Apache prayer that ends: "for all good things."

"He spoke Apache well enough for every Chiricahua in the audience to understand," said New Mexico State University anthropologist Scott Rushforth, who also consulted on the film and attended several screenings.

But there aren't that many Chiricahuas left. They were rounded up and sent to Florida in 1886, shunted back to Alabama, Oklahoma and finally to the Mescalero homeland in south-central New Mexico in 1913.

"There are only about 300 people who are fluent in Chiricahua today," Tavere told the audience Sunday.

So Ron Howard cared enough to get the Apache language right. And he may have gotten the history (the slave-raiding) right as well. Bravo.

Apache audiences understandably appreciate seeing their people and hearing their language on-screen. That may be enough to make the movie a winner for them.

This article offers only one comment on the stereotypes noted previously: that Apaches enjoyed seeing themselves portrayed "as they were—the good and the bad." True, having a variety of types is better than having only negative types—e.g., savage, stoic, or good-for-nothing Indians. But even better is having characters who are multifaceted—who have conflicting traits, both good and bad, as real people do.

It's not clear whether The Missing achieves that level of sophistication. Most (non-Indian) critics seem to think it doesn't.

What is clear is that Eric Schweig's character is unreservedly evil. That suggests the movie is at least partly stereotypical. The best villains have a touch of humanity about them. They aren't just cardboard cutouts.

The Searchers presented good Indians, as did the seminal Broken Arrow (1951) and the Lone Ranger movies, so it's not as if that's something new. Showing good Indians is a good starting point, but these days movies should strive for more nuanced portrayals.Racism present in The Missing?

Keith Uhlich sums up what many critics thought about The Missing's Indians in his Slant Magazine review:

Marketed as a Blair Witch-type horror film, The Missing is actually a racist, crocodile-tear-stained period screed sprung from the "aw shucks" psyche of everyone's favorite Andy Griffith sidekick, little Ronny Howard....Howard's view of the Indian characters, whether friend or foe, is exoticism at its worst. The white director's image of another race's humanity never extends beyond the crude idea of the noble savage.

Concludes Olinger:

For the performances and the unusual combination of genres this may be worth a rental. It's not worth 8 bucks.

Correspondents reply

One correspondent writes:

Apaches seeing some good in it suggests that there's still a dearth of proper Indian images in film and on television. When NAFPS members were discussing a remake of 'Billy Jack' (to star Keanu Reeves), one of them recalled desperately wanting to believe that Tom Laughlin was Indian and in the butt-kicking on screen, because things were so bad for Indians at the time. Maybe the popularity of 'blaxploitation' films had to do with powerless-feeling blacks wanting to see powerful, take-charge blacks beating The Man (no matter who was making those movies. If there are few images, people will flock to the ones provided.

Another correspondent writes:

I agree wholeheartedly with the arguments you present. But I have a little issue with the word Voodoo.

I understand "voodoo" has two meanings: the specific African/Caribbean religion and a general "black, dark, or incomprehensible magic" (e.g., "voodoo economics"). It's similar to shaman, which also has two meanings: specifically, a practitioner of indigenous religion in NE Asia and America, and generally, any medicine man. But I'll try to be more precise in the future.

Related links

Savage Indians

"Primitive" Indian religion

The best Indian movies

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.