We simply chose an Indian as the emblem. We could have just as easily chosen any uncivilized animal.

Eighth-grade student writing about his school's mascot, 1997

We simply chose an Indian as the emblem. We could have just as easily chosen any uncivilized animal.

Eighth-grade student writing about his school's mascot, 1997

The problem

An article excerpt explains the basic problem:

By Dr. Cornel Pewewardy (Comanche/Kiowa)

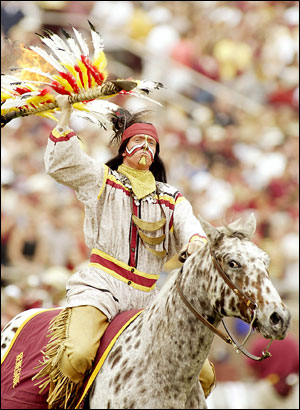

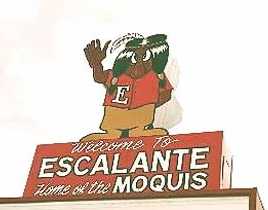

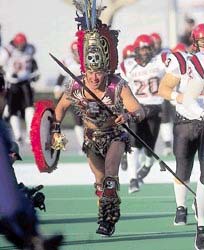

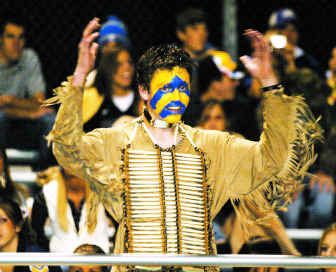

The portrayal of Indian mascots in sports takes many forms. Teachers should research the matter and discover that Native Americans would never have associated the sacred practices of becoming a warrior with the hoopla of a high school pep rally, half-time entertainment, being a sidekick to cheerleaders, or royalty in homecoming pageants. Most of these types of activities carry racial overtones of playing Indian in school events. Some teams use generic Indian names, such as Indians, Braves, or Chiefs, while others adopt specific tribal names like Seminoles, Cherokees, or Comanches. Indian mascots exhibit either idealized or comical facial features and "native" dress, ranging from body-length feathered (usually turkey) headdresses to more subtle fake buckskin attire or skimpy loincloths. Some teams and supporters display counterfeit Indian paraphernalia, including foam tomahawks, feathers, face paints, and symbolic drums and pipes.

They also use mock-Indian behaviors, such as the tomahawk chop, dances, chants, drumbeating, war-whooping, and symbolic scalping. These negative images, symbols, and behaviors play a crucial role in distorting and warping Native American childrens' cultural perceptions of themselves as well as non-Indian childrens' attitudes toward Native Americans. Most of these proverbial stereotypes are manufactured racist images that prevent millions of students from understanding the past and current authentic human experience of Native Americans.

What's wrong with Indian mascots, anyway? From Take Me Out of the Ball Game by Holly Beck, 1/31/05:

Forty years after the civil rights battles of the 1960s, Native Americans and civil rights advocates are still fighting a decades-old battle to end the depiction of American Indians on football helmets, basketball courts and team jerseys. They say such images foster a shallow and inaccurate understanding of Native American cultures, reinforce stereotypes of the noble savage or red-faced warrior, and encourage racist behavior among sports fans.

.

.

.

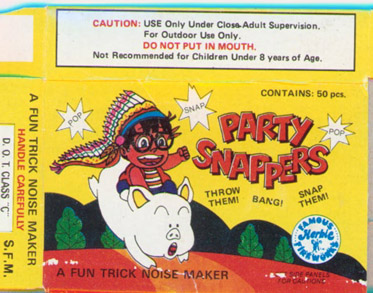

Part of the problem, says Jacqueline Johnson, of the National Congress of American Indians, is the complete inaccuracy of most representations by sports teams. "You'll see icons or pictures that are not reflective of the people or cultures," she says. "They become caricatures, and that's offensive in itself, as it would be to any other race if they were caricatured."

From Bill Plaschke's column in the LA Times, 8/7/05:

"These names and images have a damaging effect on Native Americans because it freezes us in our past, it distills our humanity to a one-dimensional term," said Joseph Gone, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan who once fought for the elimination of mascot Chief Illiniwek when he was a student at Illinois.

From Nicknames & Mascots: Complicity in Bigotry by Keith M. Woods (Poynter Institute, 8/17/05):

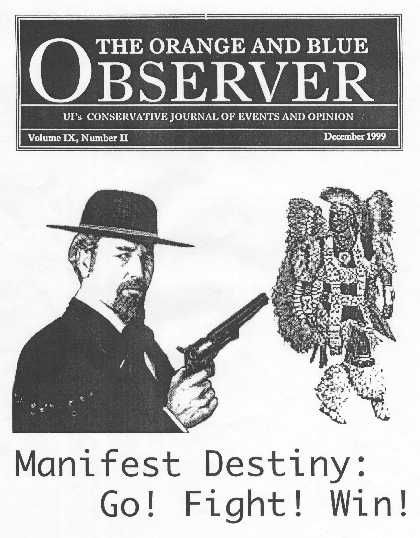

The harm here is not that all Native American nicknames are insults on the order of Washington's Redskins. It's that nearly all of them freeze Native Americans in an all-encompassing, one-dimensional pose: the raging, spear-wielding, bareback-riding, cowboy-killing, woo-woo-wooing warriors this country has caricatured, demonized, and tried mightily to exterminate.

A document titled "What's Wrong With Indian Mascots, Anyway?" (source unknown) tries to answer the question it poses:

Because virtually the only image that non-native children view of Native people are of the mascots, most children assume that Native people are dead or were war-like people. This stereotype diminishes the Native culture and is hurtful to Native people.

Our myths and legends that the Native people were bloodthirsty killers are perpetuated by the mascot. These myths are what are psychologists deem "dehumanization," which is necessary in any war to justify the killing of people. In other wars, we can remember the names used for Germans, "krauts," Japanese were "Nips," etc. But when wars are over we drop those names and show respect once again for people who are not our enemies. We have never dropped those names and perpetuate a war like attitude towards Native people by the continuance of those names.

For a refutation of the claim that being called war-like is an "honor," see Smashing People: The "Honor" of Being an Athlete.

In an interview with CBSNews.com, 3/20/01, author Sherman Alexie (Spokane/Coeur d'Alene) adds another important point:

"The mascot thing gets me really mad" Alexie says. "Don't think about it in terms of race. Think about it in terms of religion. Those are our religious imagery up there. Feather, the paint, the sun that's our religious imagery. You couldn't have a Catholic priest running around the floor with a basketball throwing communion wafers. You couldn't have a rabbi running around."

"A genocide of the mind"

VIEWPOINT: A genocide of the mind

By Chase Iron Eyes

Published Sunday, November 18, 2007

AURORA, Colo. — The heart of the problem is a conceptual flaw in the practice of using Indian logos. We don't want change simply because we disagree semantically with the word "Sioux". No, we want change because our very identity is under attack.

This issue is not about Indians complaining about degrading treatment from non-Indians. This is about our own existence.

Since we lost control of our spiritual self-determination, it has been very hard for our children to learn that their sense of self-worth comes from our living religion.

A transformation happened when a collective Euro-American consciousness began to dictate what is the essence of an American Indian. This transformation made the existence of Indian nicknames possible.

But the practice of using Indian nicknames is evidence of that transformation. This transformation also is called "objectification."

The most devastating aspect of Indians as nicknames and logos is the objectification of our race.

Objectification goes back to the days of the papal bulls that claimed non-Christians had no rights of their own, as well as to stories about the white experience in Indigenous country. Stories were widespread about "the savage red men just beyond the frontier."

The very fact that a group of folks tried to "define" a culture demonstrates that "Sioux" identity was under attack from a forceful objectification that would supplant all conceptions, even our own, of Indian identity.

No longer are we living our identity; we are looking at it through a lens created by the European — a lens in which Indians are inferior and whites are superior. We are looking through a lens created and shown by the use of Indians as team nicknames and mascots.

Inevitably, we judge our own "Indianness" based on the whole of our life experiences and learning. Largely, the whole of our learning consists of foreign perceptions and views on the world, learned in schools, on TV and from other outlets.

Creating a team name based on a race of people makes it easier for Indians and non-Indians to sense that object group (Indians) as something different than the group using the nickname (humans).

This process is dehumanization. It is the subtle shift in thinking that takes place when we are used as team nicknames.

The Indian nickname dilemma is so dangerous because it is doing significant damage while a large portion of us are unaware of it. Because the objectification of Indians is so widespread, accepted and institutionalized, we unwittingly buy into the idea that Indian team nicknames are harmless.

In reality, this objectification is undercutting our self-esteem and it is damaging the way the world sees us.

It is our cultural/intellectual resources being taken from us — our identity. We get nothing but ridicule and disdain for our faiths, cultures and identities. Our kids and people are still subjected to scorn for our identity when they see that our essence is being objectified.

Why has the Indian nickname and logo remained? People see this as something not affecting their day-to-day lives. But make no mistake, the problem is not abstract; this practice causes damage to our own individual and national self esteem.

By not allowing our essence to be misappropriated and outright disrespected by others, we are promoting proper spiritual, mental and emotional health for our wicoicage or future generations. We will not see this debate go away any time soon. It will remain so long as Natives with informed senses of identity survive into the new millennium.

Iron Eyes is a UND graduate and a member of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe.

Mascots aren't the only problem

Chad Smith, principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, explains how mascots are representative of a larger problem. From Indian Country Today, 9/2/01:

"Actually the mascots are a small part of an overall issue and that is of Indian imagery. In that you have public domain cartoons, movies, nicknames, icons, logos, commercial appropriation of Indian images — it goes on and on. You have to look at each one of those and do an analysis.

"The analysis I use is twofold. The first one is called Anaweg, that is my 8-year-old daughter. Does it teach her the truth about Indians? If the image doesn't, I have no use for it. The second is Nedsin, that is the name of my deceased father. Does it honor our ancestors? If it doesn't, I have no use for it. That is how I look at all the stuff I see about Indians.

"The image of Indians follows a long pattern of appropriation," Smith said. "Illegal appropriation often, land, water, resources, our children. So when they appropriate, they believe they have property rights to that imagery and that's not true. The exception is that we have a high school called Sequoyah High School. Indian schools are the only schools in the country that are entitled to refer to themselves as Indian. That is our form of identity. Other schools are not entitled to do that. They are basically appropriating our identity."

Mascots are just the most blatant example of Native stereotyping in our culture. Other examples include the chiefs, braves, and maidens seen in movies, TV shows, and cartoons. In an essay titled 'Red Face' Does Not Honor Us (Snag Magazine, 2/1/05), H. Mathew Barkhausen III explains how ubiquitous the images are:

Corporations all over the United States that have named their companies with some sort of "Indian" name, and companies have created corporate logos and trademarks with an "Indian" theme in mind. From the ridiculous photos on the door of the trucks of the "Navajo" trucking company depicting a Native woman in stereotypical "Indian princess" garb, and for some bizarre reason, with deep blue eyes, to the other "Indian princess" depicted on the "Land O Lakes" butter packages, stereotypical images of Native Americans are everywhere.

So non-Indian America is misusing and abusing Native images, including mascots. Even if this is true, some people argue, it's a trivial issue. Why worry about it when Indians suffer from poverty, crime, and substance abuse?

Rennard Strickland provides the answer in Changing Mascots Doesn't Signal Failure, Lack of Honor (Muskogee Phoenix, 9/14/06):

The question of mascots is significant for Native Americans. It transcends sports and entertainment. It influences law. It dominates resource management. It profoundly impacts every aspect of contemporary American Indian policy and shapes both the general cultural view of the Indian as well as Indian self-image. No groups other than the Indian face the legal situation in which their land, as well as their economic, political and cultural fate, is so completely in the hands of others. That is so because of the way in which substantial tribal resources are held "in trust," with the management and regulation, if not always operation, resting with the federal government as "trustee." The result is that the non-Indian in the U.S. Congress and in the executive branch control the fate of Indian peoples and their resources when they legislate and administer practices and policies.

The Indian image is, therefore, an especially crucial and controlling one because it is that image (often reflected in mascots like the Redman) which looms large as non-Indians decide the fate of Indian people. If the non-Indian decision makers continue to view native people as dinosaurs, as redskins or warriors, as happy hunter on the way to extinction, the policy will be different from what it would be if the decision–makers saw beyond the mascot and the stereotype.

More than just hurt feelings

If the harm of stereotypical mascots isn't self-evident, Dr. David P. Rider makes it evident in Stereotypes/Discrimination/Identity:

Nowhere are such negative appraisals of minority groups more blatant than in the mascots and Indian names of sports teams that proliferate in the American education system. While other minority groups in America must endure negative stereotypes, Indians are the only minority group that has those stereotypes advertised in government-funded public schools. Indian mascots help to promote and perpetuate the dehumanizing stereotypes that developed among European colonizers centuries ago. As such, they are harmful to both Indians and nonIndians. Indians endure the psychological damage of seeing cartoon-like caricatures of themselves embodied in the mascots, perhaps the ultimate in dehumanizing victims. It is no coincidence that Indians have the highest suicide rate, school drop-out rate, and unemployment rate of any group in the United States.

From Bill Plaschke's column in the LA Times, 8/7/05:

Gone said he was stunned by the effect that the chief's presence had upon the racial attitudes on campus.

"When I got there, I thought, sure, a mascot could be relevant," he said. "But then I saw how the Native American students on campus felt cheapened, they would have things thrown at them, they underwent a very bitter experience."

Even if a school presents its team name and mascot tastefully, Rider notes the meta-message of linking Indians to sports in "Indians" and Animals: A Comparative Essay:

Despite immense diversity in the size, geographic location, history, and educational specialties of the various colleges in America, most share one strikingly common feature: Eight of the ten most common nicknames for college sports teams are beasts of prey (Franks, 1982). In order of popularity, the top ten college nicknames are as follows:

1. Eagles

2. Tigers

3. Cougars

4. Bulldogs

5. Warriors

6. Lions

7. Panthers

8. Indians

9. Wildcats

10. Bears

Of the eight predators on this list, it is interesting to note that seven are either individual species or generic collections of species whose numbers have declined precipitously in the past 500 years, hunted to the brink of extinction. The exception, bulldogs, is an artificial creation through selective breeding. The progenitors of bulldogs, wolves, were hunted to the brink of extinction just as the other predators on the list were.

The preponderance of nicknames used for American college teams conjures up images that evoke fear and loathing in Americans. Indeed, these species were eradicated because of the images Americans concocted for them, the contempt Americans held for them, and the fact that they occupied land that Americans wanted for themselves.

Franks' top-ten list is based on the total number of college sports teams that bear those particular nicknames. The two names that do not reflect predatory animals, Warriors and Indians, both refer to humans indigenous to the Western Hemisphere. College teams named after Indians are actually underrepresented in Franks' list. Excluded from the overall count of "Warriors" and "Indians" are all the American college teams named for individual Tribal groups, including Apaches, Chippewas, Fighting Sioux, Pequots, and Fighting Illini. In addition, numerous college teams sport nicknames of generic Indian themes, among them the Chiefs, Chieftains, Braves, Redskins, Redmen, Tomahawks, and Savages. As Franks notes, if all the college teams with nicknames associated with American Indians were combined, their number would exceed that of its nearest rival by a considerable margin.

Or as Suzan Shown Harjo put it in The NCAA Is Learning What It's Like to Be Indian (Indian Country Today, 8/11/05):

Most of the commentators on this issue lump "Indian" sports references in with the bears, tigers, banana slugs, geoducks and leprechauns. They don't seem to notice that they are species hopping from humans to creatures and mythical beings, and that only the "Indians" are based on living people.

Political correctness run amok?

Some people believe this—and other cases of stereotyping—are examples of political correctness run amok. But as another quote from Dr. Pewewardy (Indian Country Today, 3/15/00) shows, Native people are hardly dogmatic on the subject of mascots:

You have to understand that I'm not totally against all Native mascots. I am against negative Native mascots. I think people have to define that. It's negative if it is a caricature—big nose, big teeth. Something like that shouldn't be in schools. It is a negative message.

We are trying to prevent stereotypes from happening, but with these mascots and caricatures the image is negative. That is what they send out. The children are impacted by those symbols. I rarely see positive good stereotypes in mascots.

In Tribes Protest Use of Fighting Sioux Nickname, Logo (Grand Forks Herald, 3/27/05), mascot foes Charlene Teters and Daniel Green express similar views:

In a perfect world, Teters said, indigenous image and representations would be used sensibly. And universities would promote cultural studies that combat stereotypes and teach students the value of cultural symbols and the true history of the people behind them.

But since real life is not perfect, it will take generations before tribal nations facing a "sickening list" of socioeconomic problems recover, Green said.

Until then, he said, rallies such as this will help to restore some of the native pride and true identity.

In fact, Indian mascots occasionally receive a Native seal of approval. From Take Me Out of the Ball Game by Holly Beck, 1/31/05:

Many sports fans profess as much devotion to their teams' racially-charged Indian mascots as to the players themselves, insisting that the mascot is a tribute to this country's native peoples. Supporters point out that there are many Native Americans who say they are not bothered by their likeness on a jersey or football helmet. Perhaps the most famous group to have willingly lent its name to a sports team is the Seminole tribe in Florida, immortalized by Florida State University's Florida Seminoles.

But critics of the Florida Seminoles point out that while the team logo and mascot uniform are sanctioned by the Seminole tribe, the behavior of sports fans at home games is not. The school's respectful tribute to the Seminole nation, crafted so carefully in collaboration with the tribe, crumbles quickly when keyed-up sports fans start hollering ‘war chants' and doing the ‘tomahawk chop' at halftime. Advocates for change also argue that the consent of some Native Americans does not lessen the hurt and embarrassment felt by others, all so that sports fans can have an image to rally around.

See Why FSU's Seminoles Aren't Okay for more on the subject.

It's important to note that most professional and college teams don't make the same effort as Florida State's Seminoles. Then what? Is it "political correctness" to oppose Native images when they're literally (not figuratively or politically) incorrect?

Redskins vs. Niggers

The classic comeback to a typical mascot supporter is: Would you support a team called the Peoria Kikes or the Birmingham Niggers? If not, how do you justify the continuation of a name like the Washington Redskins?

Someone actually tried this thought experiment once. From Rennard Strickland in Changing Mascots Doesn't Signal Failure, Lack of Honor (Muskogee Phoenix, 9/14/06):

Perhaps, at this point, one should note that there is certainly no movement to "honor" other social, ethnic or religious groups such as African American or Asian Americans by transforming them into sports team captions. Many years ago the National Conference of Christians and Jews created a satirical T-shirt with such fictional mascots and the protest was so great that they quickly withdrew the shirts.

Case closed? If they're so sure they're right, why don't some mascot supporters try to name a collegiate team the Fighting Sambos or whatever? Prove to us that other racially based names are equally harmless. (One intermural team did name itself the Fighting Whites, but that's not the same thing. The "Fighting Klansmen" would've been the same thing.)

For more on this argument, see Little Black Sambo and Chief Wahoo. Of course, some people are too obtuse to understand even this:

I guess if I lived on a reservation and a high school was nicknamed the "Iroquois Pale Faces" I would be offended....But that's not the perspective I'm working from. Nope, this is the all common-sense channel....There is absolutely nothing wrong with Indian-related names (Russin, 1998b, p. 1A).

In other words, "If I were in your position, you'd be right. But since you're in your position and I'm not, you're wrong." In other words, many white people are incapable of rational thought on the mascot issue. Scary.

In his San Francisco Chronicle column of 5/3/01, Jon Carroll dispenses with the "PC" argument:

The opponents of sundry name-change proposals are always drawing up lists of counter-examples. Hey, Notre Dame is the Fighting Irish — is it supposed to change? How about the Trojans and the Spartans — do they not promote unhealthy stereotypes? Those Minnesota Vikings; is that not an unjust depiction of the sensitive native people of Scandinavia?

Such rants usually end with a common invocation: "Where will this political correctness end?"

("Political correctness" is the great bludgeon that we at People Against Change will always keep ready to batter our opponents with no matter what the issue. If the term had been around in the 1840s, the movement against slavery — with its pious pamphlets and geeky speechmakers — would have been mocked as politically correct. "I'd like to see those fancy liberals do without their fine cotton shirts," someone would remark to thunderous applause.)

The many voices of opposition

Carroll adds that the people against mascots are hardly a tiny, whiny liberal minority:

The battle against Indian nicknames has been going on for quite some time. It is not three cranks with a Web site; it's a major movement of people who believe that policy follows culture and that the sooner "Redskins" becomes as unacceptable a nickname as "Jewboys" or "Ragheads," the closer this nation will get to dealing with the poverty, disease and alienation among the Indian population.

Robert Eurich elaborates on the opposition. His response to a New Hampshire-based editorial was published in Foster's Online, 9/1/01:

Aside from the obvious fact that American Indian people represent less than one-percent of the national population and almost certainly constitute and even smaller percentage of New Hampshire's peoples, the plain truth is that individuals such as the editorial writer are not hearing what many American Indian people have been saying about this issue for years because they do not want to hear or are just not listening.

Were it otherwise then official position statements taken on this issue by virtually every responsible American Indian advocacy organization in the country would be respected and heeded. Such organizations include the Washington, D.C., based National Congress of American Indians, which is the oldest, largest, and most representative entity of its kind, the American Indian Movement, the Association on American Indian Affairs, Indian Psychologists of the Americas, the Native American Journalists Association, Concerned American Indian Parents, Advocates for American Indian Children, and any number of other reputable groups. Even the highest governmental civil rights body in the country, the United States Commission on Civil Rights, which is chaired by Elsie Meeks, a highly respected Lakota woman, has officially endorsed retiring institutionalized "Indian" sports team tokens from public schools. What more does the editorial writer want? Something written in blood?

Supporting Eurich's point are lists of hundreds of organizations opposing Indian sports team names and mascots. The organizations range from the NAACP to the National Education Association to the United Methodist Church.

Native American Organizations That Endorse the Retiring of Native American Mascots

Also supporting the point: "Over 500 Native organizations, hundreds of tribes and petitions with signatures in the tens of thousands have called for the retirement of these mascots," according to "What's Wrong With Indian Mascots, Anyway?" As Carroll said, it ain't three cranks with a website.

The hard numbers

A roundup of American Indian opinion leaders, published 8/7/01, confirms that Native people don't think the "honor" is an honor:

In a survey by Indian Country Today, 81 percent of respondents indicated use of American Indian names, symbols and mascots are predominantly offensive and deeply disparaging to Native Americans.

"Do Indian mascots predominantly honor or are they predominantly offensive to Natives?"

Honor 10%

Offensive 81%

Unsure 9%

In UND: Bellecourt Criticizes Nickname (Grand Forks Herald, 11/26/02), activist Vernon Bellecourt refers to

a recent survey done by a Cherokee Indian group of 14,000 of its members. That poll, he said, found that 85 percent of respondents thought it was time to eliminate the use of Indian nicknames.

A North Dakota poll reported on In-Forum.com, 9/9/05, says that

63 percent of American Indians said UND should change the name if the state's Sioux tribes formally request it....

Many non-Natives agree. For instance, here's a report from NativeTimes.com, 11/14/03, titled "Another Poll Shows Public Support for Mascot Change":

Tulsa radio station KRMG is asking listeners " Do you agree with the Union School board's unanimous decision to keep the Native American mascot and team name "Redskins?". Results indicate an overwhelming majority, 81%, say they do not. Nineteen percent agree with the school board.

The poll comes on the heels of two other recent surveys about mascots. NewsTalk WDWS AM asked listeners if the University of Illinois should retire its Chief Illiniwek mascot. According to the station, 63% of respondents believe the mascot should be changed while only 37% say no. In response to a query asking if the district should lose the "Redskins" mascot, KTUL Newschannel 8 reports a whopping 78% agree the mascot should be changed. Twenty-two percent opts to keep the status quo.

Native views should carry the most weight, of course. But some polls suggest mascots don't bother Native people much. The much-maligned Sports Illustrated poll got the ball rolling on this contrary claim.

Unfortunately, its methodological flaws are overwhelming. I'd say it's almost worthless as a statistically valid representation of Native views.

Apathy explained

From Take Me Out of the Ball Game by Holly Beck, 1/31/05:

"There are happy campers on every plantation," said Harjo, an American of Cheyenne and Muscogee descent. She is certain that the majority of Native Americans oppose the use of their identity in team names and mascots, and that the evidence lies in Morning Star Institute's long court battle with the Washington Redskins over its name and noble-savage mascot. "Every major national Native American organization supports our position, and in our years of litigation against the Washington Redskins, they have not been able to produce one Native person in court to support them."

Still, it seems fair to say many Natives don't have strong opinions about mascots. If they did, they'd be marching in huge numbers against offensive sports teams. Instead, they leave the mascot battles to vocal activists like Harjo.

Some articles help explain this apparent apathy. From 'Red Face' Does Not Honor Us by H. Mathew Barkhausen III:

One-dimensional representations of Native Americans are not only common, but thought to be "no big deal" by most non-Native Americans. This apathetic attitude of society has often spread to the Native American community itself with many Native people unwilling to speak out against it for fear of being ridiculed by those who don't understand why these images are indeed a big deal.

From a piece titled What's in a Nickname? in the Philadelphia Inquirer, 12/10/04:

Bensalem resident Cyenh Witmer, 50, a mother of three and acting chief of the Eagle Clan, an inter-tribal cultural association based in Bucks County, agreed with Schwarzenegger.

"Native Americans have been trying for years to get rid of names like Neshaminy and Ridley [the Green Raiders] use," said Witmer, a full-blooded Lenape (Delaware) and Chinook. "To me, it's, 'Who cares?' They'll get around to changing the names."

.

.

.

According to the University of Pennsylvania's National Annenberg Election Survey, a poll conducted from October 2003 to September 2004 showed only 9 percent of 768 Native Americans -- and 13 percent of the college graduates among those polled -- found the NFL Redskins name offensive.

Witmer gives every indication she would be with the majority in such a survey. But her stance resonates with stinging pride.

"We were the first Holocaust, when you think about it," said the Ridley High graduate, who was born on the Penobscot Reservation in Maine. "I've lived my whole life with demeaning [names]. So I pick my battles.

"If that school wants to call itself the Redskins, it's OK by me... . I'm proud of my culture and heritage."

Note the contradictions in Witmer's views, which I suspect are commonplace among Indians. She doesn't care about the "Redskins" name, which is "OK" by her...but she's lived all her life with "demeaning" names. She picks her battles and won't choose this one, but she expects the name to change eventually.

When examined further, the North Dakota poll provides similar results:

[W]hile 63 percent of American Indians said UND should change the name if the state's Sioux tribes formally request it, only 35 percent of statewide residents agreed.

When asked if they are offended by the nickname, 61 percent of North Dakota's American Indians said they are not, compared with 95 percent of people in the state's overall population.

To summarize, 61% of Indians said they aren't offended, but 63% said UND should change the name. How's that for a complex and contradictory position?

Perhaps a lot of Indians think mascots are wrong intellectually but don't feel they're wrong emotionally. If so, surveys that ask Indians if mascots "offend" them are missing the mark.

Asking the wrong questions

Ignoring the probable flaws in the "official" surveys (the Sports Illustrated poll, the National Annenberg Election Survey, etc.), we're left to wonder how accurately they capture the ambivalent views of Native people. Natives like Witmer seem to be looking for anything that bolsters their "culture and heritage"—even something as lame as a sports team name. What if the poll gave them a choice: to be honored by a football team or a national museum? Which do you think they'd choose?

In general, Indian cultures teach people to avoid confrontations and keep their feelings private. How likely is it that a Native person will confront a (white) poll taker and say, "Mascots don't honor us, they oppress us." Few people want to sound like a complainer or a victim when they can stand tall and act proud instead.

The psychology of being a historically oppressed minority may explain why Native people don't oppose mascots wholeheartedly. In Need to Tell Stories About Natives Fuels Pen (Lincoln Journal Star, 6/24/02), Jodi Rave elaborates:

One of the few consistent images our young people get from the media come in the form of Native-based sports mascots. Stephanie Fryberg, a Stanford University psychologist, and a co-worker have been researching indigenous students' reaction to how they felt about Native peoples' names and images used by sports teams.

The last time I reported on the results, they looked like this: 50 percent of indigenous high school students said they opposed Native mascots; 50 percent said they didn't mind. But overall, 90 percent said they felt it was disrespectful. When asked why they didn't mind being used as a mascot even if they felt it disrespectful, Fryberg said, students responded: "It's better than being invisible."

Fryberg seems to have asked the questions that other polls didn't. Questions like "How can you tolerate mascots if you find them disrespectful or demeaning?" and "How do you really feel about them?" The answers bring us closer to the truth.

Let's reiterate the bottom line of Fryberg's research: 50% of indigenous students oppose Native mascots and 90% say they're disrespectful.

The evidence is in

As Eurich suggested, what more do mascot lovers need? Must someone read to them the many books, websites, and petitions demanding that mascots go—like parents reading "See Dick Run" to unschooled children? Perhaps if they study the US Patent and Trademark Office ruling that the "Washington Redskins" trademark is derogatory, they'll get the point.

How about if demonstrators travel cross-country to protest outside their offices—as they have for Cleveland Indian and Atlanta Brave games? Does someone have to get arrested burning a Chief Wahoo logo to show the depth of feeling? Because that's happened too.

No, these things won't make a difference. Much like creationists or Holocaust deniers, mascot lovers are willfully ignorant of the voluminous evidence against their position. If they spoke to every one of the nation's millions of Indians and learned the majority oppose team names and mascots, they'd invent other excuses for their opposition.

That's how racism works. It isn't rational or it wouldn't exist. As naysayer Russin showed above, even if people admit the harm, they can simultaneously deny it matters.

The solution

If the non-belligerent Irish were upset by Notre Dame's nickname, or the Sons of the Vikings by the NFL franchise in Minneapolis, I'd consider changing these names, too. I don't think an insulting team name is worth defending in the grand scheme of things. The world is lousy enough that we don't need to be promoting harmful stereotypes in schools, in sports, or anywhere else.

Carroll's response to the Fighting Irish, Fighting Sioux, Fighting Illini, et al. is even simpler:

Whenever a significant number of people identified with a subsection of the human species objects to a name, then the name gets changed.

'Nuff said.

Mascots in the Stereotype of the Month contest

Seminoles' black helmets imply Indians were spearchuckers

AL baseball headline: "Indians scalp Red Sox to even series"

NCAA gets Muzzle award for trying to ban Indian mascots

Illiniwek activists are part of a "powerful grievance industry"

Tenn. school's Chief Win-Em-All, "Reservation" are "history"

Sports DJ on NCAA: "Paleface know what best for redskin?"

Mascot defender: Harvard "would've slaughtered the Indians"

Volleyball "Warriors" don headdresses to show school pride

Dartmouth Natives "on the warpath," portrayed as a scalper

Anti-Redskins movement is "ultra-liberal initiative full of PC"

Stanford Indian caricature appears on frat and alumni shirts

U. of Florida cartoon: NCAA scolds Gator killing Seminole

Ark. liquor store mural shows Indian with scalp, war club

Mascot slogan ideas: "Scalp the Indians," "Char the Chiefs"

Products named after Indians have "debasing depictions"

Indian names are an "honor" to some, a "tradition" to others

"Anti-Indians" want to remove every Indian name in the US

"Condescending" NCAA tells Indians what's best for them

NCAA thinks "Seminoles" is stereotype, not actual name

Mascots are "simply romantic, adulatory generalizations"

Dobbs: Mascot ruling is an "Orwellian exercise," "idiotic"

NCAA decides for Indians "without their express consent"

NCAA "Thought Police" are telling Indians what to think

Redskins "Piss on Dallas" decal features big-nosed Indian

Chief Illiniwek okay because he's derived from traditions

Football video game shows fan wearing Chippewa regalia

Illiniwek protesters are "malcontents" throwing "Tantrum"

Tulsa-area high school hosts "Redskins for Christ" website

Bizarro depicts "Big Chief Tablet," "Atlanta" the brave, tipis

Head: "Cowboys scalp 'Skins to maintain NFC East lead"

Fein: Activists = "spoiled children of political correctness"

T-shirt shows loincloth-wearing "brave" dangling by rope

Mesa State College headline: "Mavs scalp Sioux 31-24"

Mohawk Carpet is proud of infantile Tommy mascot

"Braves" protesters dress like Plains Indians in cartoon

Mascot does "war dance," chops body at Okla. school

Columnist: Aztec "dining habits" involved eating hearts

Arrow Chevrolet mascot is a naked, big-nosed Indian

French "Smart Buffalo" resembles big-nosed aardvark

Cartoon shows chief and boy wanting to be mascots

Students call Indian "Sitting Bull," do tomahawk chop

LA Times columnist says "Redskin" slur is unimportant

Comanche proud to be a mascot, says "Call me savage!"

Minn. editorialist thinks "red skin" is onion or girl's blush

Fighting Sioux t-shirt shows an Indian mating with a buffalo

Kansas football news: "Redskins buried at Burial Grounds"

Comanche columnist: Mascots "should remain forever"

Washington Times: Mascot foe is "running a race hustle"

Baltimore Sun column: Team names are the "wrong battle"

SD school refuses to change script about warring tribes

Kan. newspaper headline: "Orioles gun down Indians"

Ga. columnist compares Indian mascots to birds, snakes

Columnist says Indian activists are "whiners" and "fusspots"

Student yells "prairie niggers" at an Indian basketball game

Editorial says Chief Illiniwek is a "venerated representative"

Spokane students dressed as Indians perform "war dance"

Birds & Blooms magazine flaunts a Chief Wahoo birdhouse

Teachers dress and dance like "Indians" at Minn. pep rally

Chief Wahoo doesn't hinder "full enjoyment" of a park

More mascot developments

Lakota thinks mascots honor him

Native orgs that oppose mascots

Indians and tigers and sharks...oh my!

How the University of Utah "honors" Indians

The Sweet Sioux Tomahawk

Dance, clown, dance!

Chief = "bridge" to nowhere

Chief rears "ugly" head

Scowling chief must go

My debate question

Let's stereotype everyone equally

Mascots don't represent reality

Catawbas stereotype themselves

McCain's mascot moment

Racist Warwick Warrior?

Mascots teach us Indians?

Indians really red-skinned?

Losing war over mascots?

Skeet shooting

Chief tosses to Braves

No more Redmen forever

"Redmen" = Sambo

Visualizing stereotypical mascots

"Fear the Spear" no more

Thrilled to be Chief

What are kids learning?

Letter on Natick Redmen

"Honoring" Natick's losers

"I was a teenage mascot"

Native American mascot culture

Mascots = appropriation

Good riddance to ASU's Indians

Flutie supports racist mascot

Natick's Redmen must go

Early mascot victories

Plains chief chosen as Uncas mascot

Indians to protest at Super Bowl

"Commit to the Indian"

Pontiacs use arrowhead logo

Fans taunt Navajo athlete

Bad medicine for mascots

Chief is still everywhere

Chief may rise from the dead

How mascots foster racism

Arrowhead replaces brave

Mascots = civil-rights issue

William & Mary drops feathers

Mascots objectify Indians

Any Indian mascot is racist

Arkansas State "honors" stereotypes

Keep the name, eliminate the offense

Lakota makes headdresses for Chiefettes

Chief Illiniwek = free speech?

Fans can't live without their mascots

My 10 Questions video on Racialicious

My 10 Questions video

Indians as living fossils

Why people support Indian mascots

Spokane team respects Spokane Tribe

Another whining Illiniwek supporter

How Arkansas State "honors" Indians

The Trail of Cheers

Chief Illiniwek on The Daily Show

Good exchange on mascots

Indians logo applauded

Erdrich says no to mascot

Mascots by the numbers

Volunteers love phony Indians

Anti-Indian award of the year

Money buys mascots

Good riddance to Chief rubbish

Offensive blacks retired, but not offensive Indians

More garbage to go

In denial about mascots

Nailing the pro-chiefers

Send out the clowns

Love the mascot, hate the Indian

Ding, dong, the Chief is dead!

Chief protected by law?

Blogging the Chief

How wrong is Chief Illiniwek?

Illini mascot isn't a mascot?

Wrong message to kids

Another stupid, stereotypical school

Chief runs out of excuses

"Chiefs" and "Maidens" must go

Hate speech at UIUC

Judge Chief Illiniwek for yourself

Defending mascots = attacking Indians

It's not just Indian mascots

Mascots bite the dust

More mascot information

American Indian sports team mascots

National Coalition on Racism in Sports and the Media

FAQ on mascots

Common themes and questions about the use of "Indian" logos

"Playing Indian": why Native American mascots must end (background info)

Academic institutions using Native names/stereotypes

Mascots in the news

Related links

Fighting the Fighting Sioux

Fighting Sioux vs. Fighting Irish

Why FSU's Seminoles aren't okay

Smashing people: the "honor" of being an athlete

Red·skin n. Dated, offensive, taboo

Author Jody David Armour's thoughts on Chief Wahoo

The harm of Native stereotyping: facts and evidence

Readers respond

"The arrowhead is 'stereotypical?' Um, er, uh, how can that be if ALL RACES OF MANKIND MOST DEFINITELY USED ARROWHEADS?"

"I was wondering if the NFL Kansas City Chiefs remain encumbered by stereotype issues?"

"[I]t is far from an absolute that mascot removal necessarily is a good thing in each and every case."

"[A] parable about a football game between the Whiteys and the Darkies" is "based on a fallacy."

"It is interesting that someone at least acknowledges the issue of non-Native American Ethnic team names."

"[C]omics, shows, and movies mock EVERYONE, so why would they leave out first-nations?"

The Indian child "has experienced the pain of an Indian mascot; he knows what it does to self-esteem and self-identity."

The warrior, who "sacrifices for his people and his beliefs, should have an honorable place in our society."

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.