Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

Fighting Sioux vs. Fighting Irish

(5/21/01)

Mainstream America's usual responses to the mascot issue include: "We're honoring Indians," "Get over it," and "What about the Fighting Irish?" These responses are all old, trite, and invalid. Indian people and their supporters have addressed them a thousand times.

Mainstream America's usual responses to the mascot issue include: "We're honoring Indians," "Get over it," and "What about the Fighting Irish?" These responses are all old, trite, and invalid. Indian people and their supporters have addressed them a thousand times.

Let's dismiss these arguments once and for all:

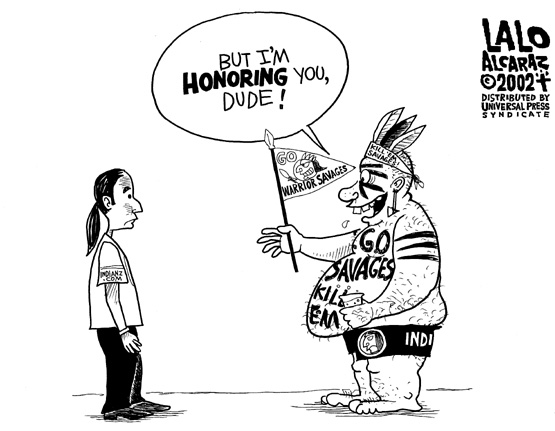

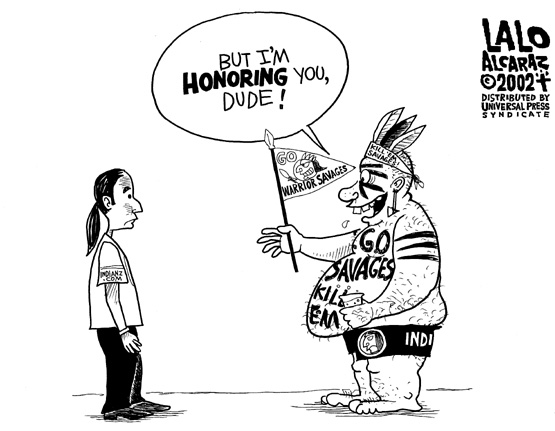

"We're honoring Indians": Only the people being honored can determine if the honor is, in fact, an honor. Indian people almost universally deny feeling honored by mascots.

"Get over it": Get over being criticized. If you don't like the criticism, either resolve the problem to make it go away, learn to like it, or get the hell out of the country.

The "Fighting Irish" argument is perhaps more substantial and deserving of consideration, so let's give it its due.

The "fighting" stereotype

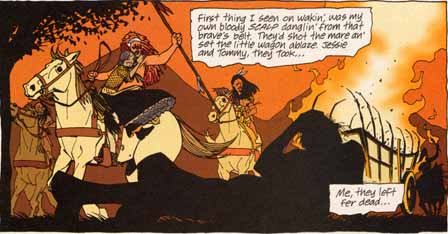

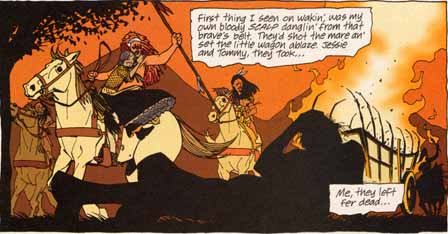

For starters, the problem with any warlike name—the Warriors, the Braves, the Fighting Sioux, et al.—should be obvious. It's a stinkin' stereotype. It compares Indians to soliders, killers, thugs, barbarians, and animals.

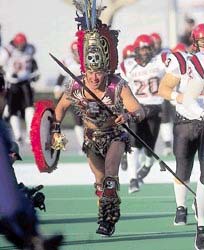

People such as the fellow below just don't get it, so here's the explanation, once and for all:

>> I am totally exasperated by those activists and journalists who continue to spout the completely illogical belief that "UND Fighting Sioux" is insulting. I have never heard anyone, Native American or otherwise, make a single successful argument to prove that "Fighting Sioux" is in any way insulting or derogatory. <<

Apparently you haven't read this posting. Read it now and weep.

>> "Fighting," of course, refers to the entire reason why the Sioux name is employed by UND athletic teams, because those teams seek to perform in the spirit of the Sioux warriors, noted for their battlefield prowess. Also, nothing insulting there. <<

Indian people understand the rationalizations for using "warrior" or "fighting" names. They understand them and they dismiss them as invalid. Having been subjected to stereotypes for ages, they understand how stereotypes work—unlike this fellow.

It doesn't matter one whit how noble or honorable you think the warrior mantle is. It's not for you to decide. How would a shy Indian mother like being "honored" for her battlefield prowess? How about an Indian version of Martin Luther King Jr.? If you think everyone likes being compared to a warrior, get out and talk to the world's population—the majority who aren't gun-toting American males.

Even if the label is 100% accurate the first time it's applied, it becomes a stereotype the more it's used. Suppose someone calls a really smart Asian man a "brain." He may be flattered the first time because it reflects his positive self-image. Now suppose people call him "brain" ten times, a hundred times, a thousand times—nothing but "Hey, brain, how's it going? Solved any quadratic equations lately?" It's patently obvious that this "honor" becomes a stereotype—a caricature if not an insult. It denies the man's full humanity by portraying him as an egghead and nothing else.

The "warrior" label is analogous. It caricatures Indians as one small part of their totality. Many Indians were warriors only when forced to defend themselves—and many were never warriors at all. Why would they want a name that barely applies to them, if it applies at all?

So sports fans have reduced a complex people to a cardboard cutout—a stereotype. But still, goes the argument, these fans mean to honor Natives, not insult them. Shouldn't we acknowledge their intent?

No. The "honor or insult" dichotomy is false because a stereotype doesn't have to be insulting to be harmful. Reducing a people from three dimensions to one is itself a harmful act.

But don't take my word for it. The evidence of stereotyping's harm is long and varied. I've posted some of it at The Harm of Native Stereotyping: Facts and Evidence.

If this were the first or second time Native people had received this "honor," it might not be annoying. They might shrug it off just as Asians shrug off being labeled "nerd" or "geek." But Indians have heard that they're warriors, raiders, marauders, wild men, and savages a million times since 1492, and they're understandably sick of it. I would be too if I were in their position.

Indian activists confirm point

Confirming the point, a mascot fact sheet titled "What's Wrong With Indian Mascots, Anyway?" says:

Because virtually the only image that non-native children view of Native people are of the mascots, most children assume that Native people are dead or were war-like people. This stereotype diminishes the Native culture and is hurtful to Native people.

In the Online Athens newspaper, 8/27/01, Edwin Poulin, a Sioux from South Dakota, testified that

the spearheads and Warrior chief logo that decorate Oconee County High School are offensive. He would support their removal, he said, because they do not paint an accurate picture of what Indians represent.

The spearheads and other Warrior imagery indicate aggression and battle, something that is not part of modern Native American culture.

"The (Native American) warriors of today are not the warriors who take lives," he said. "The warriors of today are the ones who can heal people. The warriors are the single mothers and single fathers who raise their children and keep them off drugs, who are family, (who are) responsible toward each other."

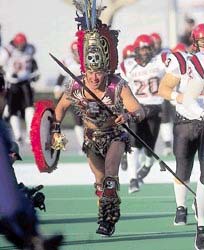

Note that the figure in the photo wears a Plains Indian headdress, inappropriate for a southeastern Native from Georgia. The figure also has bare legs, inappropriate for any dignified Indian "chief." This is a superhero costume, not actual Native clothing.

So the image is phony, which proves this school, at least, isn't honoring local Natives. Whom is it honoring, then? A fictional warrior only vaguely related to the Indians who existed. That's about as accurate as dressing a Pilgrim as a pope...or as a Jew.

If you're a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant, would you be honored to be called a Nazi soldier? Why not, since Hitler's troops were known for their ferocity, their battlefield prowess, their singleminded devotion to a cause? A peaceful Cherokee farmer whose ancestors came from Georgia is no more related to a Plains Indian warrior than an American WASP is to a German Nazi.

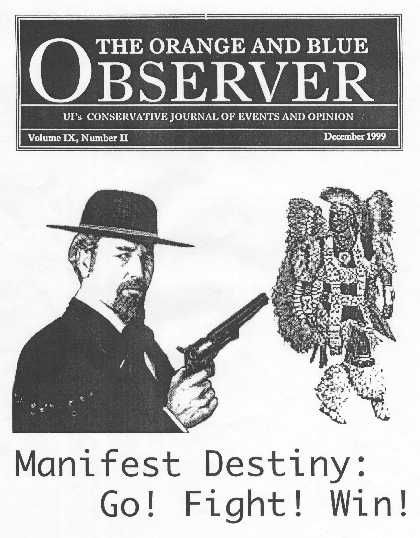

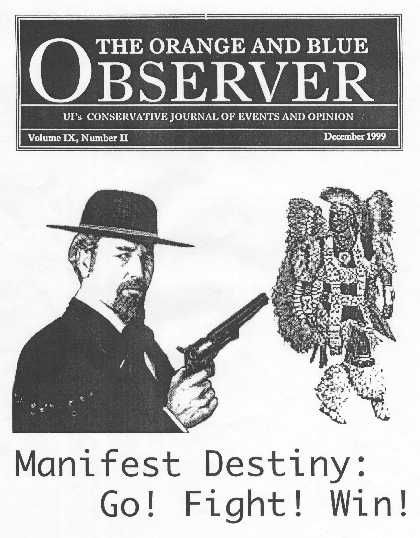

Just as athletes honor Indians, I've honored George W. Bush by comparing him to another bold, fearless, uncompromising leader. For more on the honor issue, see Smashing People: The "Honor" of Being an Athlete.

>> I challenge anyone to make a successful case to prove that "Fighting Sioux" is in any way insulting. It can't be done because it is an honor, not an insult. <<

It's done. You lose the challenge. Better luck next time.

Not clear on the concept yet? How much simpler can we make it? The warrior image is a stereotype. An Indian warrior is neither a ferocious savage who carries weapons intending to fight or kill, nor a thuggish athlete who seeks glory by battling and defeating others. Neither association is an especially great honor.

Note whom sports teams tend to honor: Fighting Sioux, Fighting Illini, Apaches, Mohawks—i.e., Natives with a reputation for being tough or ferocious. If there's a team named after the Hopi, Pomo, Tlingit, Creek, Powhatan, Abenaki, or Inuit people, I've missed it. If mainstream Americans were honoring Indians, they'd name teams after these people. What they're honoring is their stereotype of Indians.

Moreover, "honoring" people for ancient achievements implies they're dead and gone, or at least that they haven't done anything worth honoring recently. It's a backhanded compliment, like bestowing life achievement awards for something people did 50 years ago but not for their recent work. It's not nearly as complimentary as the complimenters believe.

On to the "Fighting Irish"

Here's an online posting that implicitly denigrates the Indian position and suggests Indians should get over it, just as the Irish have:

Jeffrey M., Ph.D., writes: "How many other ethnic groups have had treaties systematically broken, had high disease and poverty due to isolation, and been mocked and looked down on?"

If he were aware of the history of England's dealings with the Scottish and the Irish, he would see the same pattern in each case. These groups came to America (the Scotch in the 1700's, the Irish in the 1800's) largely because of this, and became the "hillbillies" and "dumb Irish." But today no one is ashamed of the "Mountain Man" or "Fighting Irish" mascot.

My reply:

- I doubt any group of people has had as many government treaties broken as American Indians have.

- I believe the Irish potato famine was triggered by a biological blight, not by genocidal government policies.

- Americans did look down on and stereotype the Irish and other immigrants when they first arrived, but these ethnic slights have largely disappeared. Native stereotyping began long before the immigrant stereotyping of the 19th and 20th centuries and continues to this day.

- Nobody considers the Scottish "hillbillies" or "mountain men" anymore. If that stereotype ever existed, it's long gone. The Scottish are more commonly known as gruff, eccentric penny-pinchers. A better example of a current stereotype would be Italians as Mafiosos or Arabs as terrorists.

- Irish Catholics founded Notre Dame and intended its team name and mascot to honor their history. Native Americans did not choose most Indian team names or mascots.

- "Fighting" isn't a trait associated with the Irish these days, so "Fighting Irish" isn't particularly harmful. Being a savage or a warrior is still a stereotype associated with Indians, so it perpetuates our biased cultural beliefs. If the Irish supported a major sports team called the Drunken Irish, then we could talk about a comparable stereotype.

- From what I've seen, most Indians are more concerned about mascot images (e.g., Chief Wahoo, Monty Montezuma) and actions (e.g., dancing at halftime, doing the tomahawk chop) than they are about mere names like the "Fighting Sioux" (University of North Dakota).

- With people like John F. Kennedy, Tip O'Neill, and Ronald Reagan holding the reins of power, the Irish are no longer a marginalized group. Indians still are. When you become the group in power, you can and should expect to to be the butt of more jokes, satires, and stereotypes about your behavior. Marginalized groups who still feel the pain of injustice are not appropriate targets for insults that continue the injustice.

- "Scotch" is a drink, not an adjective describing things Scottish, but that's another matter.

To put it in simpler terms, you don't kick people if and when they're down. Not if you want to consider yourself a morally upstanding person, that is.

Robert Eurich's thoughts

More points to consider from mascot-fighter Robert Eurich:

- According to some sources, with which I agree, the Great Hunger, the worst of several famines, was principally exacerbated by British policies concerning export of goods, landlord/tenant relationships, commodity prices, etc. In short, I have heard that it was not merely a shortage of food brought on by the biological blight but the deliberate policies of the British that caused the greatest devastation.

- Irish are white Europeans and part of the dominate society. Irish-Americans represent the 2nd largest sub-ethnic group in the country. Although much assimilating admixture has taken place, American Indian people were obviously not of white European origins. Today American Indian people represent less than 1% of the nation's total population. American Indian people were historically disenfranchised and generally remain so to this day. The same cannot be said for Irish-Americans.

- The institutionalized use of "Indian" sports team tokens is very profuse. Those mascots, nicknames, symbols, and logos representing the Irish are relatively scarce.

- A Leprechaun, such as is used as Notre Dame's mascot, is a fictional, imaginary character. A central concern regarding the use of "Indian" tokens is their dehumanizing nature that turns living American Indian people into unrealistic, fantasized objects. Placing American Indian people into the same category as a clay pipe smoking imp known for stealing pots of gold is one clear example of how the dehumanizing objectification is facilitated.

- This is not a question of "Since the Irish aren't offended neither should Indians take offense." Because of vast historical and contemporary differences between these two groups that is an incongruent "apples to oranges" comparision. The comparision itself smacks of a certain ethnocentrism that suggests groups other than Irish are somehow askew because they do not think "the way the Irish do" about this matter.

The simple truth is that, regardless of the reasons, many American Indian people have expressed the desire to see "Indian" tokens retired. One would think that in itself should be enough. However, accepting the twisted logic of the argument, *if* the Irish were offended by certain practices involving their religious beliefs and ethnicity then those engaging in the offenses should take such concerns seriously and act accordingly. Indeed, such was the case when Stanford University twice insulted the Irish and Catholicism (see 3rd Apology for Stanford Band Antics).

Nevertheless, similar offenses against Amerian Indian people no doubt repeatedly occur throughout the nation on a regular basis and yet are accepted without question.

Robert

Good points, Robert. I agree with you.

More on the leprechaun from Irish correspondent Jamie:

IMO, the leprechaun caricature is to the Irish what Aunt Jemima is to African Americans, in short a degrading stereotype. The leprechaun depicted on Lucky Charms and other such places is close cousin to the image of Paddy depicted in anti-Irish political cartoons of the 19th century, and perhaps into the 20th as well. The leprechaun carries hints of the non-white and less-than-human status afforded the Irish for hundreds of years.

If the Irish want to be portrayed as inhuman creatures that are troublesome at best and evil at worst, that's their prerogative. But why would Indians want to be put in the same category?

More arguments distinguishing the Irish from Indians

From For Dignity's Sake, Stop Using Indians as Sports Mascots by Tim Giago. In the Houston Chronicle, 9/17/05:

Let's consider some of the arguments I received by mail and e-mail after my last column on mascots. What about the Fighting Irish? The University of Notre Dame, in its early days, was composed of many Catholic priests of Irish heritage. The school mascot was chosen from within by the Irish priests. At sporting events the "Irish" mascot does not depict the worst characteristics of the Irish people. The Fighting Irish sports fans are not waving whiskey bottles in the air as weapons or as a demonstration of a supposed Irish trait.

From Darken Up, A-Hole: Reflections on Indian Mascots and White Rage (8/10/05) by Tim Wise, recounting a barroom discussion with a mascot fan:

"What about Notre Dame?" he shot back. "The Fighting Irish. What about that? My ancestors were Irish," he continued (ah yes, one of those Irish Indians), "and it doesn't bother me one bit!"

Of course, the comparison was utterly unconvincing. To begin with, to be called a fighter is not the same as to be called, or typified visually as a "savage." There is a qualitative difference, made all the more evident by the history of this nation: a history in which fighting Indians were slaughtered, and for whom their willingness to fight back at those who sought to exterminate them, provided their murderers with what the latter thought the ultimate justification for the perpetration of a Holocaust. Fighting Irishmen, meanwhile, got to be viewed as perfect candidates for the Union Army, or for your local police force.

In other words, one group of fighters had to be eliminated, the other, assimilated. If we can't discern the yawning chasm between these two things, well, we really should stop drinking, be it at the local brewpub, or anywhere else.

Secondly, indigenous persons, unlike Irish Americans, continue to be marginalized in the United States. A substantial percentage have been geographically ghettoized and isolated on some of the nation's most desolate land, while those off the rez have largely been stripped of the cultures, languages and customs of their forbears by a boarding school policy implemented against their families, which policy's stated purpose from the 1800s through much of the twentieth century was to "Kill the Indian and save the man."

To be Irish American is to be a member of the largest white ethnic group in the nation, and one of the most accepted and celebrated at that. It wasn't always that way, to be sure, but it is now. For Irish folks to be stereotyped as fighters simply doesn't have the same impact—given the power and position of the Irish in this society—as when stereotypes are deployed against subordinated groups. Objectification only works its magic upon those who continue to be vilified. For those on top, it can become a source of amusement, laughter—a good time.

"Yeah," I responded. "But when Notre Dame chose to call themselves the Fightin' Irish, the school was made up overwhelmingly of Irish Catholics. In other words, it was Irish folks choosing that name for themselves. How many Indians do you think were really in on the decision to call themselves 'redskins,' or to be portrayed as screaming warriors on someone else's school clothing?"

From InForum.com:

Other views: Notre Dame Irish have power; UND Sioux never did

By James McKenzie, The Forum

Published Sunday, August 14, 2005

Anthony Hebert's recent comparison (letter, Aug. 10) of the Fighting Irish and the Fighting Sioux brings up an old question, one I am familiar with because of long-time associations with both of those UNDs. I would like to address that comparison both as a graduate of Notre Dame and a 34-year faculty member at University of North Dakota.

The most important distinction between the two UND fighting mascots has to do with power. The Irish Americans of Notre Dame have it; American Indians do not, not very much, certainly not in comparison with assimilated Irish Americans. Notre Dame's Irish were involved in the choosing of their moniker many scores of years ago; North Dakota's Indians were not.

The Irish, America's earliest, poorest Catholics – they were called "shanty Irish" – have attended Notre Dame by the tens of thousands now, finding there and in business, the professions and politics at every level, legendary successes. I don't know how many Irish-American professors, deans, presidents and administrators of every stripe there have been at Notre Dame, but it would take only a few minutes to count the native professors and staff at Grand Forks' UND. And there never has been an Indian dean in Grand Forks, much less an Indian in higher office.

Moreover, unlike the Irish, who came to this country "seeking opportunity," as the cliche goes, Indian peoples are still very much seeking it. The opportunity the Irish took, once King Philip's War had nearly exterminated the Pequots, was in large measure at Indian expense. Notre Dame is in a state whose very name, Indiana, alludes to the people who died or fled further west to provide those "opportunities" by which European Americans were able to do so well. The taking of their name itself, then using it to symbolize savagery and fierce athletic "fighting" continues the conquest.

Power also explains, in part, why the issue has not come forward more forcefully until recent years. When there were few or no Indians on campus to object, when Indians were still being sent to boarding schools to, in the words of the founder of the first Indian school, "kill the Indian and save the man," they were not in any position to voice opposition, or even to notice, "The Fighting Sioux." The same circumstances prevented well-intentioned whites from recognizing the problem then either.

No matter how dignified and sincere any institution taking Indian mascots, nicknames, imagery for their own use may be, it cannot reverse the power relationship, undo the history, or control how others will exploit that stereotype.

And while we are at it, let's look at the mountains of evidence the North Central Association's accreditation team took into consideration more than a year ago when it strongly urged North Dakota's Board of Higher Education to drop the name because, "ultimately, the University of North Dakota is too good an instruction, and its leadership to important to the State of North Dakota, to let this issue continue to weakened its performance and impede its full development."

McKenzie lives in St. Paul.

How the Irish chose their nickname

From the Daily Southtown:

Offended by 'Fighting Irish,' or just green with envy?

Sunday, August 14, 2005

By John O'Brien

Staff writer

On Aug. 5, the NCAA announced it is banning Native American college mascots from postseason sports tournaments starting next year.

Odds are, within a few minutes of the announcement, some yahoo was calling in to a sports radio talk show, ranting about how my alma mater, the University of Notre Dame, should have to give up its mascot, too.

Every time the debate over team names such as "Braves," "Redskins" or "Fighting Illini" takes center stage, someone claims Notre Dame is just as guilty of insensitivity for its "Fighting Irish" nickname and leprechaun mascot.

But that argument is nothing but malarkey. There is a fundamental difference between how schools came to have Native American nicknames and how Notre Dame teams became the "Fighting Irish."

By most accounts, the "Fighting Irish" nickname originated in the 19th century as an insult against Notre Dame's athletic teams at a time when anti-Catholic sentiment was rampant in our country.

According to the university, one reported use of the term came in 1899, when Northwestern University students chanted "Kill the fighting Irish" during a football game.

While Notre Dame actually was founded by a French order of Holy Cross priests, "Irish" at that time was seen more as a synonym for "Catholics." And the connotation there was anything but positive; Irish immigrants frequently were the objects of discrimination in our WASP-dominated society — in no small part because most were Catholic.

For many of my generation who grew up in the Southland, with its large populations of Irish and Catholics, it might be hard to imagine such sneering references as these to the "Irish," which were anything but complimentary. (And even today if you venture outside the Southland to other areas of the country — and even other areas of Illinois — you'll still find that anti-Catholic sentiment, but that's another column altogether.)

Well, a funny thing happened in the early part of the 20th century: The sports teams from Notre Dame started winning. A lot. And those same bigoted fans of the other schools, who previously had been ranting against the "Irish," now had to do so with their heads down, in defeat.

Eventually, victorious Notre Dame players and fans took upon themselves the "Fighting Irish" name, a sort of collective "up yours" to all the detractors who had tried to use it to demean them.

With anti-Catholic — and anti-Irish — feelings still prevalent, many Catholics and immigrants (Irish and non-Irish alike) took to cheering for the school, and savored each win as a small victory against elements of society that sought to put them down.

After years of being known by various names — Catholics, Ramblers and Fighting Irish among them — the university in 1927 picked "Fighting Irish" as the official nickname.

For supporters of the team — including many Irish Catholics such as myself — the name remains a source of pride, an acknowledgment of all the battles our ancestors had to fight to win respect in this country.

Most Indian nicknames, on the other hand, were taken on by schools dominated by cultures other than Native Americans. Most were accompanied by mascots who were caricatures of Native Americans, meant to entertain and make us laugh, but at the same time demeaning the culture they were "honoring."

The University of Illinois, for instance, didn't get the nickname "Fighting Illini" as a way to combat negative images of Indians or as a symbol of the struggle of Native Americans in a hostile culture.

I can't say why the school chose the name, but I saw last week — for the first time in any of the reports on the controversy at the U of I — one report suggesting that "Fighting Illini" wasn't meant to represent the Illini Indian tribe at all, but to represent all of us residents of Illinois. If that's the case, why have they had an Indian mascot for so long?

But I can say to all defenders of the "Fighting Illini" nickname and all supporters of the Chief Illiniwek mascot that likening your situation to Notre Dame's is simply a ploy to distract attention from the real issue — that Native American nicknames are offensive to many members of this culture they're supposed to "honor."

And I also can say, to all the people who say, "Well, Notre Dame should get rid of 'Fighting Irish' and the Leprechaun" — Go ahead.

Really.

If people really truly are offended by either, get rid of them.

My pride as a Notre Dame alum comes from the lessons of faith, service to others, loyalty and friendship that I learned while there. It comes from the caliber of academic courses I took. And, yes, it comes from the joy I had partaking in many activities while there — including watching our sports teams.

It doesn't come from some mascot who, thanks to constant exposure on 5-hour-long football games on NBC, has long worn out his welcome.

And it doesn't come from a nickname that, while a source of pride to me, might really bother someone else.

So rename the teams the Ramblers. Call them the Golden Eagles. Honor "Our Lady of the Lake" (as the university's full name translates) with the Lakers.

True, as an Irish-American, I'd miss the symbolic value of "Fighting Irish," but my pride in my heritage, my faith and my family can't be contained to the front of a T-shirt.

John O'Brien is assistant managing editor for sports and features for the Daily Southtown. You can e-mail him at jobrien@dailysouthtown.com.

Conclusion

That concludes our discussion of the problems with the "Fighting Irish" name. For a discussion of the problems with the "Fighting Sioux" name, go to Fighting the Fighting Sioux.

Related links

Team names and mascots

The harm of Native stereotyping: facts and evidence

Stereotype of the Month contest

Readers respond

"It's time for the Indians (and native Hawaiians) to just get over it. They're not the first group of people to be conquered and they won't be the last."

"[M]ost Irish...have embraced that stereotype and made it our own, taking a perverse pride in the image we have in popular culture."

"[T]o dismiss the sufferings of a people that has gone on so long in order to try to make a point about the sufferings of another serves no true purpose."

"Just because someone calls me a bad name doesn't mean I am any less a person."

"[Y]ou are incorrect on many points regarding the Irish."

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.

Mainstream America's usual responses to the mascot issue include: "We're honoring Indians," "Get over it," and "What about the Fighting Irish?" These responses are all old, trite, and invalid. Indian people and their supporters have addressed them a thousand times.

Mainstream America's usual responses to the mascot issue include: "We're honoring Indians," "Get over it," and "What about the Fighting Irish?" These responses are all old, trite, and invalid. Indian people and their supporters have addressed them a thousand times.