An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay PEACE PARTY vs. Toxic Waste:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay PEACE PARTY vs. Toxic Waste:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay PEACE PARTY vs. Toxic Waste:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay PEACE PARTY vs. Toxic Waste:

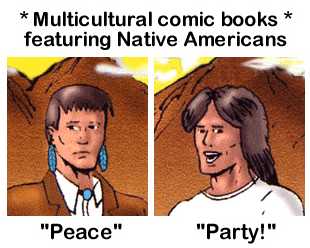

As a publisher of Native-themed comic books, I got an unusual invitation last fall: to attend a roundtable on nuclear waste.

Sponsored by the International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management (IIIRM), the roundtable's topic was the long-term stewardship of Dept. of Energy waste sites. These sites are usually decommissioned nuclear power plants or abandoned uranium mines. The problem is that their radioactive residue will remain toxic for millennia.

As one participant noted, civilization has existed for roughly 10,000 years. During that time, 400 generations of traditional people have come and gone, leaving the earth largely untouched. In contrast, the Atomic Age is only 60 years old—less than one lifetime. Yet in that short time, we've generated 10,000 years' worth of contamination.

Ironically, our descendants will have to manage these poisonous sites for as long as civilization has lasted. Another 400 generations of people will have to take care of the mess created by three generations of "cheap" energy.

That's progress for you.

The role of indigenous people

The challenge is how to retain the knowledge of physical barriers and management systems when governing agencies and technological capabilities may fail. This is especially daunting for disadvantaged communities, where many of the sites are located. These communities need solutions that are inexpensive and rely on the resources and institutions already in place.

Fortunately, indigenous cultures have the right stuff. They're as ancient and unyielding as any civilization. They've survived this long by incorporating their beliefs in their myths and rituals. They feel duty-bound to protect the earth for the countless generations to come.

In short, they're ideally suited to help shepherd radioactive sites. As an IIIRM paper presented to UNESCO in 2001 explained:

Our research demonstrates that...Indian tribes and other indigenous peoples can create stories about hazardous places that will help maintain institutional memory of the hazards found there. Stories—including songs, poems, and histories—are told over and over again, confirming and preserving local knowledge. Stories can adapt to changes in technology and governments and still maintain their central message. And stories can be produced and maintained as easily by disadvantaged communities as others. In fact, storytellers from Indian tribes and other indigenous communities often create stories in reverence of place, describing community origins, memorializing important events, and reaffirming cultural practices of a place. Such stories can also transmit information about environmental contamination that is crucial for safeguarding future generations.

Comics to the rescue

The IIIRM's people asked if I could achieve their goals using Indian comics. Specifically, if I could convey how people might recall the dangers of a site for thousands of years.

In response, I wrote a PEACE PARTY story about the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository. While this isn't a contaminated site, the basic issue is the same. How can we ensure that people will never forget the deadly waste stored there?

At the roundtable I introduced "A Story for the Ages." I made the case for telling timeless tales with larger-than-life (super)heroes. I said today's mass-market fantasies—Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter—are the equivalent of yesterday's epics—the Iliad, Beowulf, King Arthur. These are the stories people will remember an eon from now.

The art

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

The script

PAGE 1.

The panels on this page are a series of rectangles with rounded edges—the shape of a TV screen. Each one shows a scene from a TV documentary on Yucca Mountain.

In the foreground of panels 1-3, within the screen-shaped rectangle, two people are seated in easy chairs. On the left is a middle-aged Indian woman: Eunice Sanchez. She has long hair (tied up), wears no makeup, and is dressed in a flannel shirt and jeans. Her body language is stiff and confrontational. She's clearly representing the working-class people in the struggle against the nuclear repository.

On the left is a younger Anglo man in an expensive suit: Bob Butler. He's clearly the documentary's host. He listens intently to the woman but offers no response.

The five screens take up the entire page. They should have the same proportions as a standard TV screen. That may mean leaving space between each row of panels. That's okay; we can put the characters or their dialog in the space between rows.

The screens are arrayed in rows of two, two, and one. The fifth panel is centered alone at the bottom of the page. The space around this screen is blank to accommodate word balloons and captions.

PANEL 1. Sanchez is lecturing Butler and leans forward to press her argument. In the background, as if projected on the wall, is an aerial photograph of Yucca Mountain. It takes up the whole wall and thus fills the background of the TV screen.

More pix of Yucca Mountain

Yucca Mountain

1. CAP (above the screens): "YUCCA MOUNTAIN"

2. SANCHEZ: —ignore the fact that the mountain is in a volcanic area, a Class 4 earthquake zone, and sits atop a crucial aquifer. If a quake hits or the water table rises, everyone's drinking water could be contaminated.

3. SANCHEZ: Ignore the fact that 50 million people live within half a mile of the transportation routes. These poor lambs face an increased risk of radiation exposure, toxic-waste spills, and terrorist attacks.

PANEL 2. Sanchez continues to lecture Butler. Perhaps she waves a finger at him. Behind them, the background shifts to a photo of Yucca Mountain's northern portal.

More pix of Yucca Mountain's portals

Northern portal

Another portal

4. SANCHEZ: Ignore the fact that this land still belongs to the Western Shoshone by the Ruby Valley Treaty of 1863. And that the US Constitution says treaties are "the supreme law of the land."

5. SANCHEZ: When the Shoshone and Paiute tribes gather here each spring and fall to worship, what do you think they'll find? Mother Earth with a gaping hole in her gut.

6. SANCHEZ: It's a clear violation of our religion.

PANEL 3. Sanchez continues to lecture Butler. Behind them, the background shifts to a photo of an interior tunnel. A squarish utility train takes a couple workers into the depths of the earth.

More pix of Yucca Mountain's interior

Tunnel #1

Tunnel #2

Tunnel #3

Tunnel #4

7. SANCHEZ: Ignore the fact that the administration's own scientists said they couldn't be sure the nuclear waste would stay contained for 10,000 years.

8. SANCHEZ: The president said he'd stop the project if "sound science" couldn't guarantee the site's safety. Instead he's forging ahead.

9. SANCHEZ: He lied to us, Bob. He politicized the process.

PANEL 4. Sanchez and Butler are no longer visible. The background image takes up the whole screen. Now it shows a crowd of protesters walking in the middle of a road in the Nevada desert. They're carrying peace signs and signs saying things like:

10. SIGN: Say no to 'nukular' waste!

11. SIGN: End environmental racism!

12. SIGN: Save Newe Sogobia (Nevada)!

13. SANCHEZ: There's one problem we haven't addressed.

14. SANCHEZ: How will we inform our descendants 10,000 years from now that radioactive waste is buried here?

PANEL 5. The screen shows the universal symbol for radioactive: the three-pronged shape in a circle. Behind it the screen is blank. The symbol seems to glow slightly, as if it itself is radioactive.

15. CAP: "Surely a warning sign—"

16. CAP: "There was no civilization 10,000 years ago."

17. CAP: "Who knows what will happen to civilization in the next 10,000 years?"

18. CAP: "War, an ecological disaster, even a meteor strike could destroy modern society."

19. CAP: "Like Rome, America's little empire could crumble into dust."

20. CAP: "The passage of time would obliterate books, computer discs, even signs made of metal or stone."

21. CAP: "Everything we take for granted, even our language, could vanish."

PAGE 2.

At the top of this page are two more rectangular panels with rounded edges—again, shaped like a TV screen.

PANEL 1. The screen shows Yucca Mountain in the background from the ground level. It looks pristine, untouched by human hands, as it must have 10,000 years ago. Except for what's described below, there's no sign of any human presence—no technology or development.

In the foreground is a roadside marker shaped like a slab or obelisk. It's made of some long-lasting substance, probably metal. Near the top of it the radioactive symbol is inscribed. Below that are several rows of indecipherable printing.

On the right is a young man. He has a walking stick in one hand and a knapsack on his back. He's wearing a white robe and seems vaguely futuristic. He looks perplexed, as if he doesn't know why the old man is yelling at him.

1. CAP: "We Indians know all about losing our language."

2. OLD MAN: Foriru, vi trompi! C^i tiu estas toksa mals^par forj^et! *

[Note: The circumflexes go above the previous letters: the c, s, and j.]

3. YOUNG MAN: What is it? Some sort of sporting event?

4. CAP: * Get out of here, you fool! This is a toxic waste dump!

PANEL 2. This panel is just an empty TV screen for the credits.

5. CREDITS:

A Story for the Ages

Words: Rob Schmidt

Art: Mike Dorman

Letters: Kurt Hathaway

This publication was produced for the International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management and was supported by a grant from the Citizens' Monitoring and Technical Assessment Fund. [in small print]

PANEL 3. This panel shows the room in which the TV set sits from the TV's perspective. It's Billy Honanie's apartment. Billy is seated on the couch, hunched forward, watching the screen intently. He's wearing the usual shirt and slacks. The glow of the screen is visible on his face.

Behind him and the couch, Drew Quyatt has just entered the room. He's wearing the usual t-shirt and jeans. A slogan on the t-shirt reads:

Waste Not

If the apartment is visible in the background, it has the usual living-room furniture. Shelves full of books should be lining the walls, perhaps with a lamp or kachina doll on them. Where there aren't shelves, paintings should be hanging on the walls.

6. DREW: What'cha watching, 'cuz?

7. BILLY: A documentary on Yucca Mountain.

PANEL 4. Small panel shows a closeup of Drew pretending to yawn.

8. DREW: Sounds fascinating. <yawn>

PANEL 5. Still seated in the same position, Billy continues to watch the show. Drew stands beside him and also watches.

9. BILLY: Shh—!

10. SANCHEZ (from screen): So that's the challenge, Bob.

11. SANCHEZ (from screen): Despite our shortsighted "whatever" mentality, we have to find some way to tell people 500 generations from now that they're sitting on a radioactive pile.

PANEL 5. Billy gets up, perhaps to turn off the TV. As Billy speaks, Drew smiles and waves his hand dismissively.

12. BILLY: I can't imagine how—

13. DREW: Easy!

PANEL 6. They face each other. Billy looks perplexed and Drew is happy to explain.

14. BILLY: Huh? How?

15. DREW: Billy, Billy, Billy.

PANEL 7. Closeup of Drew.

16. DREW: How many times do I have to tell you about the power of our traditions?

17. BILLY (from off-panel): ?

18. DREW: Our oral traditions, m'man. And I don't mean brushing after every meal.

19. DREW: I'm talking about the power of storytelling.

PAGE 3.

PANEL 1. Head shot of Drew explaining himself. Behind his head is a flashback panel with rounded edges. It shows Indian people in simple clothing climbing out of a hole. They emerge into what appears to be the bottom of the Grand Canyon.

1. DREW: Our people have told the story of our origin forever—

2. DREW: —how we emerged from the third world into the fourth and spread across the land.

PANEL 2. Another flashback panel with rounded edges. It shows a Hopi elder speaking to a group of Hopi children.

More pix of Hopi children

Hopi children

3. DREW: We've encoded this story in our beliefs and rituals. Every song and dance reminds us who we are and where we came from.

4. DREW: Nothing has changed since the first telling. Not a word has been lost.

5. DREW: We've kept this truth for ages—a lot longer than that radioactivity will last.

PANEL 3. Closeup of Billy as he and Drew continue talking. He looks skeptical.

6. BILLY: Okay, I get it.

7. BILLY: Yes, that might work for a small, isolated tribe. But what about—?

8. DREW: It's the same in every culture. People don't remember the facts from 2,000 years ago. They remember the stories.

PANEL 4. Another head shot of Drew explaining himself. Behind him is another flashback panel with rounded edges. It shows a montage of images: Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (with their nudity obscured); the Trojan Horse; Cleopatra raising an asp to bite her in the neck.

9. DREW: Adam and Eve.

10. DREW: The Trojan Horse.

11. DREW: Cleopatra making an asp of herself.

12. SOUND EFFECT (snake): sss

PANEL 5. Closeup of Billy as he and Drew continue talking. He looks thoughtful as he considers Drew's proposition.

13. BILLY: True—

14. DREW: And what about Noah's Ark? Every culture has a legend of a great flood.

PANEL 6. Another flashback panel with rounded edges. It shows Noah's Ark on a storm-tossed sea. Rain pours from the dark clouds overhead.

15. DREW: It was the flooding of the previous world that forced us to climb into this one.

16. BILLY (from off-panel): Scientists say the flood stories may commemorate a catastrophic event. Perhaps the Mediterranean broke through the Bosporus and poured into the Black Sea.

PANELS 7-8. Billy and Drew continue talking. Billy begins to get excited as he explores Drew's theory.

17. DREW: Bospor-what? Wasn't he the guy on "Charlie's Angels"?

18. BILLY: No. He...it...oh, never mind.

19. BILLY: The point is, I think you're on to something.

20. DREW (in a small voice, as if to himself): I'm glad you said "on to something" and not "on something."

PAGE 4.

PANEL 1. Head shot of Billy explaining himself. Behind his head is a flashback panel with rounded edges. It shows a volcano erupting in the pine-covered Pacific Northwest. The outline of a thunderbird is visible on, above, or behind the volcano. This indicates that the volcano represents an angry thunderbird to the nearby tribes.

1. BILLY: According to Vine Deloria*, the Pacific Northwest tribes tell of an angry thunderbird to explain a volcanic eruption centuries ago.

2. SOUND EFFECT (volcano): rummmble

3. CAP: * "Red Earth, White Lies."

PANEL 2. Closeup of Billy as he and Drew continue talking. Maybe Billy snaps his finger as he comes up with a key idea.

4. DREW (from off-panel): If the Vine-man wrote it, it must be true.

5. BILLY: In fact, a tribe could use a story to warn future generations as well as recall past events.

PANEL 3. Another flashback panel with rounded edges. The scene is a green valley nestled in a mountainous area of Iceland. It focuses on a typical water well: a hole surrounded by a cylindrical wall made of rocks with a rope and bucket looped over a beam above.

On the well's wall, a little elf-like figure perches. He looks at the reader malevolently, rubbing his hands together, as if he intends to attack anyone who comes too close.

6. CAP: "I just read a travel story about Iceland that addressed the subject. It claimed the Icelanders—"

7. CAP: "—er, the Icelandians—"

8. CAP: "—er, the natives of Iceland dreamed up elves to keep people from polluted wells."

9. ELF: <chortle>

10. CAP: "Subsequent generations forgot what was wrong with the wells, but they never forget what the nasty elves might do to them."

PANELS 4-5. Billy and Drew continue talking.

11. DREW: There you go. If we can find an elf to guard Yucca Mountain, we're set.

12. BILLY: As stewards of the earth as well as storytellers, our people would be the natural ones to maintain a vigil.

13. BILLY: But even if they crafted a legend, there'd be a problem.

14. DREW: Hm?

PANEL 6. Head shot of Drew explaining himself. Maybe he snaps his finges. Behind his head is a flashback panel with rounded edges. It shows a long, serpentine dragon with a sharp ridge along its back from above. This dragon is roughly the shape of Yucca Mountain as seen from the air. (See photographs.)

15. BILLY: Indians don't have the concept of radioactivity in their tradtional cultures. They had no need to scare people away from toxic sites.

16. DREW: Simple, Billy Bud. We couch the story in symbolic terms.

PANEL 7. Head shot of Billy responding. Behind his head is a flashback panel with rounded edges. A great horned toad has replaced the dragon. It has roughly the same shape and size, but it looks like a real animal.

17. DREW: "Once upon a time, a ferocious dragon lived where Yucca Mountain is now."

18. BILLY: Indians didn't have dragons, either.

19. DREW: Okay, killjoy.

20. CAP: "A great horned toad lived where Yucca Mountain is now."

PAGE 5.

PANEL 1. Another flashback panel shows the toad smashing through a forest, breaking or flattening trees, and stomping into an Indian camp or small village. Men, women, and children flee from their shelters and cooking fires. The toad's forelegs send people and huts flying; its whipping tail sends trees and boulders flying.

The people are dressed simply in buckskin clothes. There are no chiefs or warriors with feathers. Their shelters are simple structures made of branches. There are no teepees. Their tools include baskets and grinding stones. They have no horses, guns, or anything that came with the Europeans.

See The North American Indians for pictures of the people, clothing, shelters, and artifacts.

1. CAP: "Day and night, the toad terrorized the people."

2. SOUND EFFECT (fleeing people): yi-i-i!

3. SOUND EFFECT (toad crashing through forest: KRSSSH!

4. CAP: "They fled before its wrath or died under its feet."

PANEL 2. Another flashback panel shows Indian warriors shooting arrows or throwing spears at the toad. These weapons are like pinpricks to the toad, clearly ineffectual against its tough, scaly hide. The toad roars in response and the warriors look scared, as if they know they can't defeat this monster.

Pix of Shoshone and Paiute warriors

Shoshone warrior on horse

Shoshone warrior (at bottom)

Shoshone Indians

Paiute Indians

5. CAP: "The mightiest warriors fought valiantly, but nothing could harm the toad."

6. SOUND EFFECT (warriors): Yah!

7. SOUND EFFECT (toad): NNNNNNN

8. CAP: "It looked as if the land was doomed."

PANEL 3. Another flashback panel shows a single Indian youth standing before the toad. He's dressed simply, not like a warrior, and doesn't have any weapons. Instead he plays a tune on a simple, roughhewn flute. The toad looks at the youth as if it doesn't know what to make of him.

9. CAP: "One youth wasn't afraid. He approached the toad with only his flute."

10. CAP: "Perplexed at why the lad wasn't attacking, the creature merely watched."

PANEL 4. Another flashback panel shows the youth talking to the toad. He holds the flute as if he's talking between snatches of playing. The toad begins to look dazed or hypnotized.

11. YOUTH: Hurting and killing people must be hard work. Wouldn't you like to rest?

12. YOUTH: Just sleep a little and you'll wake up refreshed. The people will have time to multiply, so you'll have more morsels to eat.

13. CAP: "The youth led the toad to a sleeping place where it fell into a deep slumber."

PANEL 5. Another flashback panel shows the youth walking and playing on his flute. Notes rise and are carried away by the wind. The toad follows tamely, lulled by the soothing music.

14. CAP: "What the creature didn't know is that it would sleep forever unless it was wakened."

PANEL 6. Another flashback panel shows the toad lying on the ground, sleeping. With the passage of time, it has become buried under dirt and grass. It resembles Yucca Mountain as seen from the air.

In front of the panel are the heads of an Indian mother and child. She looks down at him and talks to him sternly.

15. CAP: "Mountains rose and fell. Ice came and went. Time and tide buried the toad under dirt and grass. And still it slept on."

16. CAP: "Millennia passed. People forgot the buried monster. But each mother warned her children about the winding ridge."

PANEL 7. Billy and Drew continue talking.

17. CAP: "Do not go near the sleeping giant."

18. CAP: "If you wake it, a terrible evil will rise and scourge the earth."

19. BILLY: Not bad, but there's still a problem.

20. BILLY: This is a tale our people would tell their own children. But the goal is to warn the entire planet, including folks who have never heard of us.

21. BILLY: How would a publicity-shy people convey their message worldwide?

PAGE 6.

PANEL 1. Head shot of Drew explaining himself. Behind his head is a flashback panel with rounded edges. It shows the northern portal of Yucca Mountain—but with a twist. Some modern-day Indian people, in shirt and jeans, have been shanghaied into slavery. They're pulling carts of material into the tunnel entrance as if they were pack animals. Around them, a group of stormtroopers in high-tech armor stand guard over the Indians. Some crack whips while others hold vicious-looking dogs.

1. DREW: Simplicity again. Instead of making it a traditional tale, make it a modern-day adventure. With larger-than-life heroes and state-of-the art effects.

2. SOUND EFFECT (cracking whip): krack!

3. SOUND EFFECT (groaning slaves): uhhh

4. DREW: "Not so long ago, not so far away, an army of extremists captured a nuclear site on a remote reservation."

PANEL 2. Another flashback panel shows a cavern inside the mountain. This is similar to the tunnels in the photographs, but bigger. In the background are row after row of barrl-like caskets containing nuclear waste.

In the foreground, a masked, armored madman named Dr. Anarchy is shaking his fists at a panel of screens. These show the heads of the world's greatest leaders. They look worried or scared as he threatens them.

5. CAP: "Their ruthless commander, Dr. Anarchy, threatened the world's leaders."

PANEL 3. The flashback continues. In the background, the troopers are building a two-story-high cylinder that looks like a bomb. In the foreground, a young Indian is creeping away from the activity, obviously seeking to escape while no one's looking.

6. DR. ANARCHY: With the radioactive waste stored here, we've built an Omni-Bomb! Pay us a billion dollars or we'll destroy half the hemisphere!

7. CAP: "While the troopers prepared the bomb, one brave young Native escaped."

8. YOUTH (thinks): Got to find Peace Party!

9. CAP: "He alerted Rain Falling and Snake Standing, those defenders of truth, justice, and the American Indian way."

PANEL 4. The flashback continues. Outside the mountain, Rain Falling and Snake Standing confront the armed troopers. As Rain Falling gestures toward them, a fog envelopes the troops on the left. They shoot wildly at targets they can't see. As Snake Standing gestures toward them, a squardon of hawks swoops down and encircles the troops on the right. They also shoot wildly at targets they can't hit.

10. CAP: "Our intrepid heroes demolished the troops—nonviolently, of course."

11. RAIN FALLING: Try shooting through fog!

12. SNAKE STANDING: And hitting some hawks!

13. SOUND EFFECT (guns firing): POW! POW! POW!

PANEL 5. The flashback continues. Inside the cavern, Snake Standing (to the left) and Rain Falling (to the right) confront Dr. Anarchy. Dr. Anarchy recoils and flails helplessly as three of the guard dogs bite his limbs. Behind him, it appears to be raining in the cavern, and jagged bolts of electricity crackle and arc around the bomb.

14. CAP: "Faced with defeat, Doc Anarchy threatened to detonate the bomb."

15. SNAKE STANDING: Not smart to use guard dogs around me!

16. SOUND EFFECT (electricity): crackle

17. DR. ANARCHY: No, you fools!

18. SOUND EFFECT (dogs): GRRR! GRRR!

19. RAIN FALLING: My rainstorm'll short out the electricity!

PANEL 6. The flashback continues. Rain Falling and Snake Standing run for their lives as the cavern collapses, burying the bomb under tons of earth. Dr. Anarchy is nowhere to be seen.

20. SOUND EFFECT (tunnel collapsing): WHOOM!

21. RAIN FALLING: A bolt hit the master control panel!

22. SNAKE STANDING: The cavern's collapsing! Run!

23. CAP: "The still-active bomb was buried beneath tons of earth. Authorities said it was too risky to dig it out. The vibrations might trigger a death-dealing explosion."

PAGE 7.

PANELS 1-2. Billy and Drew resume talking.

1. DREW: So the bomb remained deadly for centuries to come, with only this story to remind people of the danger.

2. BILLY: Wow. You sure have an active imagination.

3. DREW: Naturally. I'm the creative one; you're the logical one.

4. BILLY: Okay, but how do we know this story will last 10,000 years?

PANEL 3. A shot of Drew's upper body as he looks upward, as if contemplating some spiritual mystery. Around his head float images of Jesus Christ hanging on the cross; Hamlet, a Danish prince dressed in doublets and hosiery, holding up Yorick's skull; Superman flying; and Luke Skywalker brandishing a light-saber.

5. DREW: The Bible and Shakespeare will be around that long. So will Superman and "Star Wars."

6. DREW: So will Superman and "Star Wars."

7. DREW: The great stories will endure.

PANEL 4. Another shot of Drew envisioning things. This time it's a brightly-lit TV screen, a couple comics books, and a Gameboy type of handheld video game. Each screen or cover has the PEACE PARTY logo on it.

8. DREW: Especially if they're put into popular formats.

9. DREW: Books, movies, comics, video games, cartoons...if the story is told in enough formats, it'll seep into our everyday lives.

PANEL 5. Billy and Drew resume talking.

10. DREW: It'll become part of our cultural heritage, the things everyone knows and understands.

11. BILLY: Like the first Thanksgiving. Or George Washington chopping the cherry tree. Or the so-called Wild West.

12. DREW: Especially if I play the lead.

13. BILLY: Huh?

PANEL 6. This time Drew envisions something as Billy looks on, as if they're sharing the vision. The vision shows a movie screen in a dark theater with an audience watching.

14. DREW: PEACE PARTY (tm): The Movie.

[Note: The (tm) refers to the little trademark symbol.]

15. DREW: Starring Drew Quyatt—that's me. With Billy Honanie—that's you—as his faithful sidekick.

16. DREW: Coming soon to a theater near you!

17. BILLY: You gotta be kidding me.

PANELS 7-8. Drew walks away, inventorying an imaginary list and ticking items off on his fingers. His words grow smaller from balloon to balloon, suggesting his voice is trailing off as he moves further away.

Billy remains in place and looks back at the reader. His face is screwed up as if to say, "Can you believe this guy?"

The final caption has a little nuclear symbol by it to remind readers of the import of the story.

18. DREW: Then we'll need statuettes, action figures, trading cards—

19. DREW: —coloring books, board games, lunch boxes—

20. DREW: —t-shirts, Halloween costumes, sheets and pillow cases—

21. DREW: —etc.

22. BILLY: What, no underwear?

23. BILLY: Why am I always the straight man?

24. BILLY: Sheesh.

25. CAP: END.

UNESCO paper (footnote #1)

In 2001 the following event took place:

Indigenous Identities: Oral, Written Expressions and New Technologies

Book Fair and International Symposium

UNESCO

Paris, France

15-18 May 2001

There Mervyn Tano of the International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management (IIIRM) presented the following paper:

Using Traditional Knowledge and Institutions to Protect Native Peoples from Long Term Exposure to Environmental Contaminants

Mervyn L.Tano, President

International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management

Denver, Colorado, USA

This paper explained how Native storytelling may be the key to the long-term stewardship of nuclear and other toxic waste:

III. Current Methods for Long Term Environmental Protection, Health, and Safety

A. Institutional and Engineering Controls

Long term stewardship activities currently range from record-keeping, surveillance, monitoring, and maintenance at sites with residual contamination posing hazards of little concern, to possibly maintaining permanent access restrictions at sites having hazards of greater concern, they are generally described as the activities necessary to maintain either institutional controls or engineered controls in place at the sites. Institutional controls are designed to control future land or resource use of a site with residual contamination by limiting land development or restricting public access to the resources. Institutional controls include physical systems (e.g., fences or other barriers), governmental controls (e.g., ordinances and building permit requirements), and proprietary controls (e.g., deed restrictions and easements). Engineered controls are barriers constructed to prevent contaminant migration or to prevent intrusion to an otherwise restricted area. Examples of engineered controls include caps and liners and monitoring and containment systems.

B. Shortcomings of Institutional and Engineering Controls

Both proprietary and governmental controls have weaknesses in terms of long term reliability. Where turnover in land ownership is likely, common law doctrines restricting enforcement by parties who do not own adjoining land can render proprietary controls ineffective; governmental controls may be preferable in such cases. At the same time, over the long term governmental controls may not be effectively enforced because political and fiscal constraints may influence a state or local government's exercise of its police power.

A draft DOE study states the problem bluntly: "there is little or no evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of enforcing and maintaining institutional controls.') A study by the National Research Council reaches a similar conclusion, noting that land use controls "for both legal and physical reasons, are very difficult to enforce."

IV. The Role of Indigenous Peoples and Traditional Knowledge

In the current debates about "long-term stewardship" of waste, not enough attention has been paid to how institutional memory is maintained in difficult transitions and over long time periods-memory that is necessary for maintaining the integrity of physical barriers and management systems. Disadvantaged communities in particular need to conceptualize cultural controls that can endure over thousands of years and reduce dependence on present-day governing institutions and existing technological capabilities that may not last far into the future. Such controls should be relatively inexpensive, take advantage of human resources that already exist within the community, and remain embedded in community decision-making processes to assure their long-term viability.

Our research demonstrates that indigenous individuals, families, and communities have expertise about the places they live and work in. Stories about ancient abandoned settlements have helped archaeologists locate these sites. At Hanford, in eastern Washington, similar stories should have helped the DOE avoid unearthing ancient burial and cultural sites had the DOE listened to tribal warnings. Moreover, Indian tribes and other indigenous peoples can create stories about hazardous places that will help maintain institutional memory of the hazards found there. Stories-including songs, poems, and histories-are told over and over again, confirming and preserving local knowledge. Stories can adapt to changes in technology and governments and still maintain their central message. And stories can be produced and maintained as easily by disadvantaged communities as others. In fact, storytellers from Indian tribes and other indigenous communities often create stories in reverence of place, describing community origins, memorializing important events, and re-affirming cultural practices of a place. Such stories can also transmit information about environmental contamination that is crucial for safeguarding future generations.

V. Recommendations and Outlook

Based on our experience, we see three problems with relying solely on federal institutional and technical approaches to manage contaminated sites. First, regulations on community access to hazardous sites are often forgotten or re-interpreted in less than a generation. Indeed, governments that enforce regulations may well disappear before radioactive hazards have abated. Changes in geology or climate that occur over the thousands of years these wastes remain hazardous will challenge any technical solution, even deep storage. These approaches simply will not protect generations into the deep future. Second, institutional and technical controls are expensive and difficult to implement. Third, institutional and technical controls are developed and implemented by people outside the affected communities. Knowledge of and respect for these controls among community members is often lacking.

Cultural 'controls' on access and use of hazardous areas address each of these problems. Poems, stories, songs, sculptures and paintings frequently outlast governments. These cultural resources can help protect future generations by conveying important information about the nature and location of contaminated sites, and describing strategies for dealing with the hazards found there. They are relatively inexpensive to implement and maintain. In later years, cultural controls may be enforced entirely through the voluntary actions of a large number of people living in an affected area. Stories create a sense of 'ownership' among community members over the management of hazardous wastes. Local awareness of the waste problem and respect for community-defined solutions will be greater than for solutions imposed from without.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Energy, Department of Defense, and other federal agencies involved in long term stewardship of contaminated sites should be working with Indian tribes and other communities to build capacity among disadvantaged communities to construct their own cultural controls for hazardous materials, and thus to manage hazardous sites more effectively and with greater self-reliance than is currently the case. Federal programs should emphasize transferring skills and knowledge, building networks, and creating cultural assets (from written documents to performances to the artists and historians themselves) that serve the needs of community members. The International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management also recommends that federal agency policies support rather than undermine community-based efforts.

IIIRM also recommends supports for on-going efforts at cultural revitalization among disadvantaged communities. American Indian tribes, for example, have faced more than a century of federal hostility towards many of their cultural practices. In the last two or three decades, however, tribes have been able to recover and re-invigorate many of these practices. Native artists, in particular, are taking up a wide array of historical and contemporary themes in their work, and play an increasingly central role in tribal life. By asking artists to address the problem of radioactive and other hazardous wastes in their communities, society will make good use of their skills in abstract and creative thinking, the kind of thinking required for time-scales of thousands of years. Society can also benefit from the ability of indigenous peoples' ability to express cogently community values and beliefs, and to move people to action in a way that regulations often cannot.

IIIRM roundtable (footnote #2)

The IIIRM invited me to attend the followup event:

International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management

Roundtable

Taking Control: Opportunities for and Impediments to the Use of Socio-Cultural

Controls for Long-Term Stewardship of U.S. Department of Energy Legacy Waste Sites

November 22-23, 2004

Executive Tower Hotel

1405 Curtis Street

Denver, Colorado 80202

Our objectives were as follows:

AGENDA

Of the bomb factories of the Manhattan Project and the Cold War in the U.S. Department of Energy's inventory, few will be cleaned up sufficiently to allow unrestricted use. Radiological and non-radiological hazardous wastes will remain, posing risk to human beings and the environment for tens or even hundreds of thousands of years. Current DOE plans for long term stewardship entail institutional controls that restrict access to sites through physical barriers (e.g. fences, warning signs) or legal impediments (e.g. zoning or deed restrictions). The National Research Council predicts, and experience has shown, that over time, these institutional controls will eventually fail.

We think that efforts should be undertaken to conceptualize and put into place, community-based socio-cultural controls that supplement those planned by the DOE. Roundtable participants will examine the objectives of DOE'S legacy management program and seek to provide answers to two questions: whether those objectives can be attained in other ways and how individuals, communities, and community institutions can assist in attaining those objectives.

The outcome

Final Report: Summary of Roundtable Findings and Recommendations

Artists remember toxic waste

More on Yucca Mountain

Yucca Mountain = environmental racism

Related links

Ecological Indian talk

Native vs. non-Native Americans: a summary

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.