Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

Why Don't "They" Like Us?

(9/18/01)

The United States is peopled by all kinds of patriots: Repressive ones, even-handed ones, annoying ones, lazy ones. The most sensible patriots, and the ones that are most needed now, are the ones who have come to terms with the difference between the real America—the messy one, the one that often makes mistakes, the one that has plenty of enemies—and the dream America that we sung about as school kids.

Stephanie Zacharek, Salon, 9/18/01

The gulf between our dream and the realities that we live with is something we do not understand and do not want to admit. It is almost as though we were asking that others look at what we want and turn their eyes, as we do, away from what we are…. This rigid refusal to look at ourselves may well destroy us, particularly now since if we cannot understand ourselves we will not be able to understand anything.

James Baldwin, "Lockridge: 'The American Myth,'" The New Leader, April 10, 1948

As Albert Einstein once said to me: Two things are infinite: the universe and human stupidity. But what is much more widespread than the actual stupidity is the playing stupid, turning off your ear, not listening, not seeing—playing helpless.

Fritz Perls, psychologist

How do I respond when I see that in some Islamic countries there is vitriolic hatred for America? I'll tell you how I respond: I'm amazed. I'm amazed that there's such misunderstanding of what our country is about that people would hate us. I am—like most Americans, I just can't believe it because I know how good we are.

"President" George W. Bush, 10/11/01

*****

Continuing the analysis of the 9/11/01 terrorist attack on America....

From the LA Times, 9/13/01:

WORLD REACTION

A Superpower's Sorrow, Comeuppance

Geopolitics: Critics of the U.S. see the attacks as a lesson to temper the arrogance and double standards of a relatively young global leader.

By RICHARD BOUDREAUX, TIMES STAFF WRITER

ROME — There is no shortage of reasons in much of the world to dislike the United States. From European capitals to the coca fields of South America to the assembly lines of Southeast Asia, the nation can appear arrogant and selfishly fixated on its own politics and interests.

Its unparalleled power makes it a lightning rod for a host of grievances brought by allies, adversaries and outright enemies.

Ghoulish scenes of Palestinians dancing and rejoicing over Tuesday's mass slaughter in New York and Washington are only the most extreme and recent public expression of anti-Americanism—or at least a wariness of American power—that has followed the United States' rise as a superpower, through conflicts in the Cold War and since. Beneath the sorrow and dismay voiced abroad this week over the deadly attacks on American cities is an undercurrent of rebuke from critics who hope that the devastation will temper what they see as the superpower's sense that it can dictate to everyone else. For much of the world, America's grief is also its comeuppance.

"People are really deeply shocked by the doomsday-like pictures," said Mirjana Bobic, a popular author and head of cultural programming on Serbian state television in Yugoslavia. "But you know, every stick has two ends, and if you are beating others, you should expect a boomerang effect."

"It's like shock therapy for the United States, not to be too arrogant," said Bagus Prasetyo, 23, who works for South Korean auto maker Hyundai in Jakarta, the Indonesian capital.

While there may be ample reasons for anger toward the United States, the nation remains a source of admiration and a magnet for immigrants from around the world—criticized more for bullying and double standards than for its way of life. Anti-American sentiment often does not extend to ordinary citizens, who bore the brunt of Tuesday's attacks.

Few U.S. enemies possess the ideology and motivation to stage suicide hijackings like the ones that sent airliners crashing into the World Trade Center and Pentagon—attacks for which no one has claimed responsibility.

Although the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 showed that America has its own terrorists, speculation has focused on extremist Muslim organizations that believe they are fighting for their faith.

Hatred of the United States, Israel's strongest ally, has risen to a fever pitch among many Palestinians and throughout the Islamic and Arab world over the past year of Israeli-Palestinian fighting.

Yet anti-American sentiment is far broader and appears to have intensified after President Bush, who took office in January, opposed a draft treaty on global warming and revived an unpopular U.S. proposal for a "Star Wars"-like missile shield.

Bush was a focus of protests this summer when more than 100,000 demonstrators besieged a Group of 8 summit in Genoa, Italy, to rail against a model for the global economy that they say neglects the poor and harms the environment. The Bush administration provoked an outcry at the U.N.-sponsored World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa, this month when its delegation walked out, protesting bias against Israel.

"There are lots of degrees of anti-Americanism, but it would be dangerous to lump them all together," said Sergio Romano, a former Italian ambassador to Moscow. "There are growing divergences between the United States and other countries, but many who are critical of America would never dream of resorting to what we saw Tuesday."

Risk of Pushing U.S. Toward Isolationism

The danger, he and other commentators say, is that Americans will perceive a uniformly hostile world and push their leaders toward unilateral action or isolationism.

The view from Moscow was harsh.

"U.S. foreign policy has been characterized by a high degree of self-confidence, complacency and intoxication with its own power following the Cold War," Vladimir Lukin, a deputy speaker of the Russian parliament and a former ambassador to Washington, said in an interview.

"If the U.S. prefers to pretend that it rules the world, such myopia will continue to result in horrible acts of terror," he added.

About half the callers to a television program called "Night Flight" in the Russian capital on Tuesday night said they were sorry for the victims of the attacks "but not for America."

In Beijing, the People's Daily advised Bush to take the disaster as "a serious warning" against "hegemonist foreign policies." A posting on one of China's increasingly nationalist Internet chat room sites said Tuesday's attacks were "the result of America being the world police."

U.S. officials acknowledge that Americans often underestimate the effect of their government's policies on people around the world.

"If President Bush goes on television and says we're going to get the terrorists and those who harbor them, that means a lot of people are going to suffer," one U.S. diplomat said. "We think we're doing it for the right reasons . . . but our policies have enormous impact, and many people have suffered a lot because of what they see as our arrogance."

A Young Know-It-All That Eclipsed Others

American arrogance, in the view of many, is rooted in part in its status as a relative newcomer to the role of superpower.

China's 5,000 years of history and advanced civilization are sources of pride for its leaders and citizens. The idea that the country has been eclipsed and often lectured by such a young know-it-all is galling, like a veteran worker taking orders from a squeaky new boss, a reversal of the reverence for age that marks Chinese Confucian thinking.

Realizing that its destiny is tied to America, the Chinese have felt powerless to challenge Washington over the bombing of their embassy in Belgrade, Yugoslavia's capital, by NATO warplanes in 1999 and U.S. spy missions off the Chinese coast.

Likewise, many Arabs and Muslims view the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as far older than the Americans perceive.

To them, the conflict is a continuation of centuries of Western meddling. They think that the West, which today includes America, declared war on Islam with the first Crusade—a Christian holy war more than 1,000 years ago. They see the establishment of Israel as the United States' insertion of Jews into the region, another step of Western conquest.

"The U.S. acts only out of its interests," said Saad Mughari, an imam who is one of the most popular preachers in the Gaza Strip.

"Where is its humanity? Where is its conscience?" asked Mughari, who sympathizes with the militant Islamic movement Hamas.

"Why does the U.S. support Israel when it has so many interests in the Arab world?"

The vast majority of Palestinians felt sorrow and not joy at the terrorist attacks, said Ghassan Khatib, a Palestinian commentator and sometime spokesman for the Palestinian Authority.

Anti-Americanism and the Legacy of Cold War

Some of today's anti-Americanism is a legacy of the Cold War, which obliged, or allowed, the United States to impose its will on people—often against the interests of those people.

Through a string of military interventions, U.S.-sponsored coups and strong-arming, countries in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and Southeast Asia got governments that were allies of the United States—but enemies of their own people. This convinced many that despite its preaching about justice and democracy, the United States followed a double standard.

Yugoslavia's half a century under Communist rule made it easy, after the Cold War, for manipulative leaders such as Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic to blame the United States for the conflicts that tore the federation apart in the 1990s.

Serbs could argue with reason that Washington's later support for ethnic Albanian nationalist guerrillas in Kosovo province amounted to a double standard. The United States punished the Serbs for atrocities but tended to look the other way when ethnic Albanian rebels killed Serbs, they contend.

America has created enemies, too, by failing to see the dark side of policies that, however well intentioned, were rife with contradictions.

One case in point was its intervention in Somalia in 1992 to neutralize warlords so that aid workers could safely feed emaciated, dying children. By 1993, when the famine was over, U.S. troops were dragged into a deadly confrontation with Somalia's biggest warlord and lost their image of humanitarian neutrality.

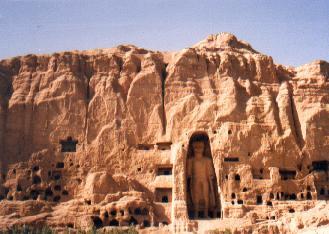

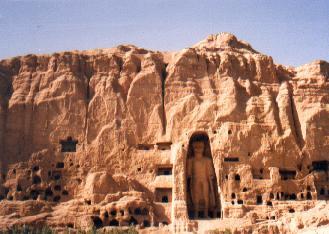

In another example, the United States provided early support for Afghanistan's Taliban militia in the 1990s, at least partly to stabilize the Afghan stretch of a route sought by Unocal, the American oil company, for an oil and natural gas pipeline that would bypass Iran.

The Taliban later gained power in nearly all of Afghanistan, but the Clinton administration did not take a stand against the regime's human rights abuses until Saudi exile Osama bin Laden's radical Islamist terrorist group, which had safe haven in the country, bombed two U.S. embassies in East Africa.

President Clinton ordered airstrikes against suspected training bases in Afghanistan in 1998, prompting Unocal to give up its pipeline project.

In the Middle East, hatred of the United States is multifaceted.

For Palestinians, anti-Americanism is largely geopolitical and rooted in the fight with Israel over land and rights. For radical Islam, which has grown rapidly as a popular movement and an armed threat, anti-Americanism is based on fundamental cultural values; the capitalist West has represented the infection of immoral values, the spreading of alcohol, drugs and pornography.

"The problem is much deeper than Osama bin Laden, or any other particular terrorist," said Shaul Shay, an Israeli political scientist who specializes in Islam. "Osama bin Laden represents a trend, a confrontation between civilizations."

In Latin America, anti-American sentiment has waned somewhat as the region modernized and democracy spread during the 1990s.

In Cuba and among Colombian narco-guerrillas, hatred of the United States is very real and brutal. Elsewhere, it is cheerfully and exasperatingly confused.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez has gone out of his way to embrace every enemy of the United States—guerrillas in Colombia, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, Fidel Castro, Libyan strongman Moammar Kadafi. Nonetheless, Chavez likes to quote Jefferson, Lincoln and Walt Whitman along with Mao Tse-tung.

Latin Americans seem to cultivate an anti-Americanism that is political, not personal.

In Bolivia, a media-savvy Aymara Indian, Evo Morales, has become a Che Guevara-like figure in the Chapare jungle, where 200,000 indigenous coca growers have fought U.S.-funded drug interdiction with dynamite and aging rifles. They chant slogans such as "Long live coca! Death to the Yankees!"

Once asked about the menacing words, Morales looked apologetic and said, "They are really referring to the system, not to the people."

*****

U.S. Roles

Some U.S. actions—open or covert—in recent decades have angered people in different parts of the world and led them to conclude that the United States ignores their interests or is hostile to them:

1954: Overthrow of government in Guatemala.

1960s: Attempts to assassinate Cuban President Fidel Castro.

1960s-'70s: Vietnam War.

1967: Support for military coup in Greece.

1967: Support for Israel in Middle East War and in subsequent conflicts with its Arab neighbors.

1967: Support for Israel in Middle East War and in subsequent conflicts with its Arab neighbors.

1973: Covert support for destabilization of Salvador Allende's government in Chile, leading to military coup.

1970s: Support for shah of Iran.

1980s: Covert and then open support for Contra rebels in Nicaragua. Secret arms sales to Iran to finance the Contras.

1986: Air attack on Libya.

1991: Persian Gulf War and subsequent sanctions against Iraq.

1992-94: Intervention in Somalia.

1995-99: Bombing campaigns to force peace settlement in Bosnia-Herzegovina and to drive Yugoslav army out of Kosovo.

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

Need more details? Okay:

Century in Review: List of US Military Interventions

A comprehensive list of US military interventions since Wounded Knee. This helps explain Osama Bin Laden's antipathy toward the West. Perhaps more important, it helps explain the Islamic world's—indeed, the rest of the world's—ambivalence toward the US.

In short, the world's people have a love/hate relationship with the US. The "hate" part of the relationship is what's caused terrorism to flourish, even if most countries officially denounce it. Increase the love, decrease the hate, and the terror may diminish.

Related links

Friendly Dictators: America's Pals Around the World

More un-American reactions

From the NY Times, 9/22/01:

VOICES OF OPPOSITION

In Europe, Some Say the Attacks Stemmed From American Failings

By STEVEN ERLANGER

BERLIN, Sept. 21 — The killing of thousands in the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington last week has prompted great unity of purpose in the United States, cemented by shared outrage. President Bush has called on the world to unite against barbarism.

While Europeans have expressed enormous sympathy and solidarity, often in emotional ways, they have also been divided in their responses. A debate has begun over whether the inconsistencies of American foreign policy, and the sheer weight of American dominance in the world, mean that resentment of the United States—even, in extreme cases, hatred—are inevitable.

There was no rejoicing or support in Europe for the killing of so many Americans. Many Europeans wept and the continent fell silent for a moment last week in remembrance of the dead.

But it has also become clear that some Europeans feel that ordinary Americans have largely floated on a tide of prosperity, triumphalism and indifference to the world since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Their view is that the United States has now been confronted with a sobering reality, and that it must try to understand. For those critics, Americans are now facing unsurprising retaliation from an important part of the Islamic world that considers America to have declared war on its faith.

The arguments are sometimes simple—America should expect war in return for bombing Iraq regularly. Some Europeans also contend that many Americans have a blinding confidence in their own goodness and so do not see that the acts of the United States are regarded in many quarters as driven by the domineering pursuit of national self-interest.

European writers and intellectuals have pointed to a catalog of actions that include the bombing—in reprisal for the terrorist bombings of two American Embassies in East Africa in 1998—of one of Sudan's two pharmaceutical factories on the challenged grounds that it was linked to Osama bin Laden, aid to Israel to buy weapons used against Palestinians, or even the American refusal to intervene to stop the mass killings in Rwanda.

Matthew Parris, a former Conservative Party member of the British Parliament, wrote in The Times of London, "The bigger they come, the harder they fall."

Disgusted by calls for quick revenge, Mr. Parris wrote: "Do they think a terrorist is like a pin in a bowling alley: one down, nine to go? Do they want to give Osama bin Laden his own Bloody Sunday? Do they not know that when you kill one bin Laden you sow 20 more? Playing the world's policeman is not the answer to that catastrophe in New York. Playing the world's policeman is what led to it."

Dario Fo, the Italian playwright and satirist who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1997, said bluntly in a widely circulated e-mail: "The great speculators wallow in an economy that every year kills tens of millions of people with poverty—so what is 20,000 dead in New York? Regardless of who carried out the massacre, this violence is the legitimate daughter of the culture of violence, hunger and inhumane exploitation."

There have been other voices that pointed to Mr. bin Laden's various enemies: not just the United States but also the autocratic Islamic governments that Washington supports, like Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Kuwait.

The Observer newspaper wrote: "America needs to recognize that, all too often, it poses as a champion of democracy while supporting regimes, such as that in Saudi Arabia, which have no proper respect for democracy."

Tariq Ali, a leftist British commentator, wrote that America was now about to wage war on Afghanistan, a country ruled by a religious movement, the Taliban, only as a result of Washington's proxy war against the Soviets.

Mr. bin Laden himself joined in that proxy battle, and became a hero partly because of that war.

"The underlying maxim is, 'we will punish the crimes of our enemies and reward the crimes of our friends,' " Mr. Ali said.

In an editorial, Le Monde wrote that America is also unreliable in the sense of appearing inconstant in its choice of allies. The United States, it noted, refused to help Ahmed Shah Massoud, the leader of anti-Taliban forces who died last weekend from injuries suffered in an assassination attempt. Yet it considers Saudi Arabia an ally, although that "is where the financial support of the Islamic radicals comes from."

Even in Germany, one of Europe's most pro-American countries, there was concern that NATO allies had somehow handed Washington a blank check. Die Zeit commented that, "The defender against terror must not act like a furious giant," adding: "The fear of U.S. hegemony is as deep-seated as the anti-American sentiment that bubbled up predictably after Bush came to power."

Anti-Americanism is almost a reflex reaction among some left-of-center French intellectuals, and there has been a predictable outpouring.

To the cry that "we are all Americans now," Marie-José Mondzain, director of the prestigious French National Center for Scientific Research, writing in Le Monde, retorted: "I don't feel at all American, but to the contrary feel redoubled in me all the reasons to condemn a world that sings along with a catastrophic president, who defends the death penalty and who has only disdain for the Middle East."

Just how self-deluded are Americans?

From the LA Times, 9/16/01:

TERROR'S AFTERMATH

Game Over: The End of Warfare as Play

By NAOMI KLEIN

Naomi Klein is the author of "No Logo."

TORONTO — Now is the time in the game of war when we dehumanize our enemies.

They are utterly incomprehensible, their acts unimaginable, their motivations senseless. They are "madmen" and their states are "rogue." Now is not the time for more understanding—just better intelligence.

These are the rules of the war game. Feeling people will no doubt object to this term: War is not a game. It is real lives ripped in half; it is lost sons, daughters, mothers and fathers. Tuesday's act of terror was a reality check of the harshest kind.

It's true: War is most emphatically not a game. And perhaps, after Tuesday, it will never again be treated as one. Perhaps Sept. 11, 2001, will mark the end of the shameful era of the video game war.

Watching the coverage on Tuesday was a stark contrast to the last time I sat glued to a television set watching a real-time war on CNN. The Space Invader battlefield of the Gulf War had almost nothing in common with what we have seen this week. Back then, instead of real buildings exploding over and over again, we saw only sterile bomb's-eye views of concrete targets—there and then gone. Who was in those abstract polygons? We never found out.

Since the Gulf War, American foreign policy has been based on a single brutal fiction: that the U.S. military can intervene in conflicts around the world—in Iraq, Kosovo, Israel—without suffering any U.S. casualties. This is a country that has come to believe in the ultimate oxymoron: a safe war.

The safe-war logic is, of course, based on the technological ability to wage a war exclusively from the air. But it also relies on the deep conviction that no one would dare mess with the U.S.—the one remaining superpower—on its own soil.

This conviction has, until Tuesday, allowed Americans to remain blithely unaffected by—even uninterested in—international conflicts in which they are key protagonists. Americans don't get daily coverage on CNN of the ongoing bombings in Iraq, nor are they treated to human-interest stories on the devastating effects of economic sanctions on that country's children. After the 1998 bombing of a pharmaceutical factory in Sudan (mistaken for a chemical-weapons facility), there weren't too many follow-up reports about what the loss of vaccine manufacturing did to disease prevention in the region.

And when NATO bombed civilian targets in Kosovo—including markets, hospitals, refugee convoys, passenger trains—NBC didn't do "streeter" interviews with survivors about how shocked they were by the indiscriminate destruction.

The United States has become expert in the art of sanitizing and dehumanizing acts of war committed elsewhere. Domestically, war is no longer a national obsession, it's a business that is now largely outsourced to experts. This is one of the country's many paradoxes: Though it is the engine of globalization around the world, the nation has never been more inward looking, less worldly.

No wonder Tuesday's attack, in addition to being awful beyond description, has the added horror of seeming, to many Americans, to have arrived entirely out of the blue. Wars rarely come as a complete shock to the country under attack, but it's fair to say that this one did. On CNN, USA Today reporter Mike Walter was asked to sum up the reaction on the street. What he said was: "Oh, my God. Oh, my God. Oh, my God. I just can't believe it."

The idea that one could ever be prepared for such inhuman terror is absurd. However, viewed through the U.S. television networks, Tuesday's attack seemed to come less from another country than from another planet. The events were reported not so much by journalists as by the new breed of brand-name celebrity anchors who have made countless cameos in AOL Time Warner movies about apocalyptic terrorist attacks on the United States—now, incongruously reporting on the real thing. And for a bizarre split second on Tuesday night, CNN's graphic "America Under Attack" disappeared and in its place flashed another one that said "Fighting Fat"—an eerie ghost graphic of what passed for news yesterday.

The United States is a country that believed itself not just at peace but war-proof, a self-perception that would come as quite a surprise to most Iraqis, Palestinians and Colombians. Like an amnesiac, the U.S. has woken up in the middle of a war, only to find out it has been going on for years.

Did the United States deserve to be attacked? Of course not. That argument is ugly and dangerous. But here's a different question that must be asked: Did U.S. foreign policy create the conditions in which such twisted logic could flourish, a war not so much on U.S. imperialism but on perceived U.S. imperviousness?

The era of the video game war in which the U.S. is always at the controls has produced a blinding rage in many parts of the world, a rage at the persistent asymmetry of suffering. This is the context in which twisted revenge seekers make no other demand than that American citizens share their pain.

Since the attack, U.S. politicians and commentators have repeated the mantra that the country will go on with business as usual. The American way of life, they insist, will not be interrupted. It seems an odd claim to make when all evidence points to the contrary. War, to butcher a phrase from the old Gulf War days, is the mother of all interruptions. As well it should be. The illusion of war without casualties has been forever shattered.

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

More on the root causes

September 24, 2001

Alienating the International Community

by Garry M. Leech

Many Americans are justifiably stunned, bewildered and angry following the recent terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington DC. But while we seek justice for these atrocious acts of violence, Americans should also reflect on why these fanatics harbor such hatred for the United States. It is not, as Washington so often claims, because they resent our "freedoms" or our "way of life"; it is because they resent a U.S. foreign policy that imposes Western cultural values on their way of life. And while the actions of this fanatical minority are inexcusable, they are indicative of a political viewpoint held by ever-increasing numbers of people around the world. Many in the international community see the United States as a rogue nation unilaterally imposing its political and economic will on the world at large.

The end of the Cold War offered an opportunity for both developed and developing nations previously separated by the bipolar conflict to unite in a mutually beneficial global community. But instead, Washington took this opportunity not to increase peace and prosperity for all nations, but to become more aggressive and militaristic in order to advance its own political and economic agenda with almost total disregard for the consequences borne by other nations.

Anti-globalization groups regularly protest the imposition of neoliberal economic policies on developing countries by the U.S.-dominated International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. These so-called "free" trade policies benefit multinational corporations and developed nations while further impoverishing people in the developing world. Hence, we find the growing international protest movement against Washington-backed global policies that has dogged economic summits in North America and Europe, and has also resulted in massive public demonstrations in many developing nations.

And regarding military policy, the United States has attacked more countries than any other nation since the end of World War II. In just the past twelve years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, Washington has launched military strikes against five different countries: Panama, Yugoslavia, Sudan, Afghanistan, and Iraq. (The total is nine countries if you include the targeting of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, the stray missiles that hit Bulgaria and Pakistan, and the chemical warfare being waged in Colombia.)

In the eight months that George W. Bush has occupied the White House, his administration has done everything possible to politically alienate the international community. The Bush Administration's refusal to participate in globally-determined policies if they in any way compromise U.S. political and economic interests has even alienated long time allies in Europe.

The list of U.S. non-cooperation over the past eight months is staggering: a refusal to participate in, or abide by, the Kyoto Protocol, the UN small arms conference, the Landmine Treaty, the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, and the recent UN conference on race. This list of non-cooperation is topped off by Bush's insistence that the United States re-ignite the international arms race by moving forward with plans to develop the National Missile Defense System.

While it is unrealistic to expect the United States to see eye to eye with the rest of the world on all matters, the Bush Administration has managed to isolate itself from, and alienate, the rest of civilization on virtually every global issue it has addressed. But President Bush is only the latest in a long line of presidents responsible for generating such resentment towards the United States. In fact, for the most part, the Bush Administration is only continuing (albeit, often escalating) many previously implemented foreign policies that have isolated the United States from the rest of the international community.

Over the years, Washington has repeatedly stood alone with Israel in voting against UN resolutions condemning Israel's military rule of the occupied territories and treatment of Palestinians as second-class citizens in their own land. Several U.S. administrations have also failed to criticize Israel's antagonistic policy of bulldozing Palestinian homes while building Jewish settlements in the occupied territories.

Rarely since World War II have conquering nations retained control over territory gained in battle. And yet, Israel continues to rule the territories it seized in the wars of 1967 and 1973. Add to this the fact that much of the weaponry used to target Palestinians living in the occupied territories is supplied by Washington (Israel is the largest recipient of U.S. military aid) and it is easy to see why many Arabs view the United States as a participant, and therefore an enemy, in the ongoing conflict.

Anti-U.S. sentiment in the Arab world is further fueled by Washington's insistence, in the face of growing international opposition, on the continuation of sanctions against Iraq. These sanctions have resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of Iraqi children due to a dire shortage of food and medicines, as well as the ongoing bombing campaign, all of which have failed to loosen Saddam Hussein's grip on power.

Americans are bombarded with viewpoints from Washington and the mainstream media portraying U.S. military actions as defensive and, therefore, justified. Terms such as "Iraqi provocation of coalition aircraft in the no-fly zone" are repeatedly used to justify air strikes against Iraq more than ten years after the purported end of the Gulf War. Meanwhile, there is no mention of the fact that, technically, coalition aircraft (U.S. and British) are flying in Iraqi airspace, which raises the question of exactly who is provoking whom. And, in light of recent events, Americans can now identify with the fear felt by many Iraqi civilians every time an enemy aircraft flies overhead.

Colombian farmers, whose crops, animals and children are being poisoned with chemicals sprayed by U.S. planes, live in a similar state of fear. The militaristic nature of Washington's drug war in Colombia through the funding, arming and training of the Colombian armed forces (Colombia is the third-largest recipient of U.S. military aid) has been widely criticized by the international community. Earlier this year, the European Parliament condemned Plan Colombia by a vote of 474-1 (see, Plan Colombia Lacks International Support).

The aerial fumigation campaign being conducted by American mercenary pilots under contract to the U.S. State Department has dumped thousands of gallons of an untested chemical concoction onto Colombian farms (see, Death Falls from the Sky). Consequently, there have been widespread reports of environmental and human health problems that that have forced many peasants to abandon their lands and join the ranks of Colombia's illegal armed groups, which have been designated terrorist organizations by the U.S. State Department. (Good Terrorists, Bad Terrorists: How Washington Decides Who's Who).

The United States has also helped sow the seeds of international terrorism by supporting and arming extremist groups that temporarily served Washington's foreign policy interests at one point or another. Among the many examples of the United States making the bed it later had to sleep in, three individuals immediately come to mind: Manuel Noriega, Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden.

Throughout the 1980's, Noriega remained on the CIA's payroll despite his involvement in drug trafficking and money laundering. The Reagan Administration was willing to overlook these indiscretions as long as the Panamanian dictator supported the terrorist activities of the Contra rebels in Washington's war against Nicaragua's Sandinista government.

However, by the end of 1989, as the Contra war was winding down and Noriega began exhibiting signs of independence, Washington decided to rid itself of the troublesome dictator by launching a huge military invasion of Panama. The official justification for the attack was the "discovery" of Noriega's involvement in the drug trade and defense of the Panama Canal, although it's not clear exactly what threat Noriega posed to the Canal's operations. During the invasion, entire neighborhoods of Panama City were leveled by a massive air assault that resulted in the deaths of as many as 5,000 civilians.

The 1980's also saw Washington provide aid and intelligence to Saddam Hussein's government during Iraq's war with Iran. The Reagan Administration supported Saddam at the same time Baghdad was sheltering international terrorist Abu Nidal and Iraqi forces were using chemical weapons against Iranian troops.

Unbeknownst to the American public at the time, Washington was playing both sides during the eight-year Iran-Iraq war that took some one million lives. The fundamentalist rulers in Iran were receiving illegal arms shipments from the Reagan Administration as part of a huge covert operation that, when discovered, became known as the Iran-Contra scandal. Washington's support for the Ayatollah Khomeini is ironic in view of the fact that Iran's fundamentalist government and anti-American sentiment were a response to the Westernization and exploitation of Iran by multinational corporations under the repressive U.S.-backed government of Shah Reza Pahlavi.

Also during the 1980's, the Reagan Administration supplied Afghanistan's Mujahedin rebels with massive amounts of aid and high-tech weaponry, including Stinger surface-to-air missiles, that helped the Muslim guerrillas overthrow the Soviet-supported Afghan government. Both the Taliban government and Osama bin Laden's terrorist organization evolved out of the CIA-supported Mujahedin rebel movement. Retired army General Makmut Goryeev, a veteran of the Soviet Union's war in Afghanistan, recently reminded Americans, "Let us not forget that he [bin Laden] was created by your special services to fight against our Soviet troops. But he got out of their control." And yet, despite the Taliban's continued willingness to shelter America's most wanted terrorist, the Bush Administration recently provided Afghanistan with $43 million in aid.

As it turns out, Manuel Noriega, Saddam Hussein, Iran's fundamentalist government, the Taliban, and Osama bin Laden all have one thing in common: They received funding and arms from Washington while being linked to international terrorism. Shortsighted U.S. policymakers failed to recognize (or were unconcerned) that once these extremists consolidated power, they would inevitably redirect their violent fanaticism against U.S. foreign policy, especially in the Middle East. Consequently, Americans are now paying with their lives for Washington's political expediency.

By launching a war against terrorism, President Bush runs the risk that history will repeat itself. In 1979, U.S. economic policies and support for the Shah's dictatorial regime in Iran resulted in a Muslim fundamentalist revolution led by the Ayatollah Khomeini. Last week, Pakistan's dictator General Pervez Musharraf acquiesced to Bush Administration demands that U.S. forces be permitted to use Pakistan as a staging ground for a war against Afghanistan. The current political situation in Pakistan is precarious and the country's large fundamentalist population is strongly opposed to the presence of U.S. troops on Pakistani soil, especially when their mission is to attack a neighboring Muslim country.

Consequently, U.S. foreign policy may once again result in the overthrow of a dictator willing to cow tow to Washington. Furthermore, a revolution in Pakistan would put anti-American fundamentalists in control of a country with nuclear capabilities.

Sadly, it is doubtful that the recent terrorist attacks against the American people will be the last, unless Washington is willing to re-evaluate its role on the global stage. While taking measures to bring the perpetrators of these horrendous crimes to justice, the United States should also take this opportunity to analyze the root causes of such anti-American sentiment. This hatred does not lie in petty jealousies over the American way of life; it is partly a result of the arrogance inherent in Washington's foreign policy.

Consequently, a military response alone, no matter how extensive, will not eliminate terrorism; in fact, it will most likely exacerbate it. The solution lies with the American people. We must realize that, while the actions of these fanatics are inexcusable, some of their anti-American sentiments are understandable. Furthermore, there are ever-increasing numbers of people throughout the world who feel the same anger towards the United States; thankfully, they have yet to resort to the same violent tactics.

In this era of globalization, it is essential that U.S. foreign policy be inclusive, not exclusive. Otherwise, the American people are likely to pay a far higher price for alienating the rest of the world than that already paid in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania.

Copyright © 2001 Information Network of the Americas (INOTA). All rights reserved.

And more:

Calamitous Perspective

Bernie Ward Interviews Phyllis Bennis

ZMag

Posted 9/13/01

Bennis: . . . crisis when we escalate the patterns of more and more and more violence.

Ward: At this point in time most Americans would say how could they escalate it, I mean, if you didn't respond militarily, wouldn't that be worse than in fact responding?

Bennis: Well, I think the very worst thing would be responding militarily to the wrong country, as the U.S. has been known to do, not too long ago, in fact, when it knocked out a vaccine company in the Sudan claiming that it was tied to Bin Laden and only six months later saying, whoops, I guess we got the wrong place. And in fact, settled with the owner of that factory for having destroyed it, not to mention destroyed the one factory in central Africa that was producing crucial vaccines for children in that impoverished part of the world. So we have to be very careful. And yes, I think it would be worse to respond militarily than to be cautious and to say let's use this to do what is so difficult at a moment like this, when we're horrified by the human toll, the human tragedy, to say let's stop for a moment and think about why is it that people around the world, so many people, are starting to hate symbols of the U.S. as symbols of oppression.

Ward: Well, now you know that you are in a huge minority tonight when you suggest that one of the things we ought to take from this is to ask the question of why committed terrorism against the United States to begin with, and most Americans are simply going to say, "Who cares?" most Americans are going to say, "It was whoever it was and we're going to go get them," and most Americans at least in the polls already that have been released, say that our support for Israel is very crucial and that, you know, this is just going to solidify . . . you, you are in a huge minority when you suggest that part of what happened today might be connected to foreign policy decisions that we have made in other parts of the world.

Bennis: But, you know what Bernie, you may be right that I am in a minority, but I think these words have to be said. We've had too many years of experience of answering these kinds of attacks with more violence. And you know what? It hasn't worked. If we're serious about ending attacks like this, we have to go to the root causes.

Ward: And what are the root causes?

Bennis: To me it's a question of the arrogance of the U.S., the policies around the world, not only in the Middle East, although that's obviously a big component, but our policies of abandoning international law, dissing the United Nations, refusing to sign conventions and international treaties that we demand everybody else in the world sign on to, whether it's the prohibition against anti-personnel land mines, support for the international criminal court, the convention on the rights of the child, for God sakes that should be a no-brainer, only the U.S. and Somalia have refused that one, you know, when countries around the world and people around the world look at this, not to mention the most recent stuff about abandoning the Kyoto treaty, threatening to throw out the ABM Treaty, that's been the cornerstone of arms control for, you know, twenty-five years, they say, "Who is this country? Why do they think they're so much better than everybody else in the world just because they have a bigger army?"

Ward: So do we deserve what happened to us today?

Bennis: No, no one deserves what happened. There's no justification. . .

Ward: Did we ask for it?

Bennis: The question is "How do we stop it?" The question is how do we stop it. And military strikes are not going to stop it.

Ward: All right. So the example of terrorism certainly is if we look at Israel, the example is that when you respond with violence for violence it does not stop the terrorism.

Bennis: Absolutely right.

Ward: And in fact we saw for the first time yesterday or the day before an Arab Israeli citizen who committed a suicide bombing, meaning obviously that even buffers between them and the West Bank aren't going to make any difference one way or the other.

Bennis: Right. Ending occupation of the West Bank and Gaza and East Jerusalem might make some difference. But certainly what isn't working is responding with more violence.

.

.

.

Ward: Make the case for why the U.S. would be so hated in the Middle East.

Bennis: I think it's hated in the Middle East because, number one, it's uncritical support to the tune of between three and five billion dollars a year in unconditional support to Israeli occupation, including providing the helicopter gunships, the F-16s, the missiles that are fired from the gunships, that are used to enforce that occupation. It's hated, number two, because it has armed these, these, repressive Arab regimes throughout the region, in Saudi Arabia, In Egypt, in Jordan, throughout the region, that have suppressed their own people, that have taken either oil money or arms to build absolute monarchies in which citizens have no rights and where the U.S. claims to support democratization of every government in the world, don't seem to apply when the U.S. seems to think it's fine when one absolute monarch dies and passes on the baton to his son, you see every U.S. official and all of their European and other Western allies flocking to the funeral to say "The King is dead, long live the new King." We see it in Saudi Arabia, we see it in Morocco, in Jordan, throughout the region. And there's enormous resentment of that kind of support. So those two sectors alone, support for the Israeli occupation and the arming of these repressive Arab regimes is enough. Now that doesn't even get to the question of the impact of U.S. imposed sanctions on the civilian population of Iraq, the bombing of Iraq, that's been going on for ten years now, all of these are things that have dropped off the radar screen of the media coverage in the U.S. but are very much front and center in Arab consciousness in the region.

From the letters to the editor of the LA Times, 2/5/03:

How Others See Us

Regarding U.S. District Judge William Young's comments at Richard Reid's sentencing (Jan. 31): Young's comment that Reid's actions were based on Reid's hatred of America's freedoms is a sad misconception that is echoed all over this country — that the world hates us because we are free.

Quite to the contrary, the world loves and respects us because we are free. It hates us because we are often arrogant, thoughtless and unappreciative of the great freedom that we have.

Jason T. Hodge

OXNARD

From The Media's Blind Spot by Eric Boehlert in Salon, 9/25/01:

Despite the disturbing silence from the press, [Professor Walter] Denny says, "The most important question we should be asking ourselves is 'Why do you think they hate us so much?' And if you look at our foreign policy that question is not too difficult to answer."

The key grievance, he says, is hypocrisy.

Arabs reject terrorism...and colonialism

From the LA Times, 9/12/01:

Some Arabs Rejoice, Others Reflect

By DONNA BRYSON, Associated Press Writer

CAIRO, Egypt — Explosions and fire, gritty ash falling like a shroud on the faces of the frightened and the fleeing. Arabs watching these television images from New York and Washington saw reminders of their own wars—and some said they rejoiced that the United States was learning a lesson in suffering.

Others condemned the celebrations in refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan and the coffee shops of Iraq and Egypt, where revelers fired rifles in the air and distributed soft drinks at news of Tuesday's attacks.

"We have to reflect on why we, as Arabs and Muslims, have sunk so low as to glorify violence and destruction," said Ahmed Bishara, a Kuwaiti political activist. "Yes, we can differ with U.S. policy. Yes, the U.S. way of life may differ. But there's no way for me as a human being to accept violence."

Others say it is America that should take notice.

"If American policy-makers are wise, they are going to try to get to the bottom of this ... American indifference," said Gamal Nkrumah, a writer living in Cairo. "A lot of people feel that the U.S. couldn't care less about the suffering of three-quarters of mankind."

Few Americans would recognize the portrait of their country in places like Ein el-Hilweh, a Palestinian refugee camp gripped by poverty and factional fighting in south Lebanon.

Ein el-Hilweh's 70,000 residents blame America's military and diplomatic support of Israel for preventing them from returning to homes they or their parents fled when the Jewish state was founded in 1948.

"I felt sorry for the victims of the New York attacks, but, regrettably, America feels no sorrow for those who are killed with U.S. weapons," said Ebtissam Shaaban, a 27-year-old hair stylist in Ein el-Hilweh.

While Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat condemned the attacks Tuesday, when news of the catastrophe broke in the West Bank town of Nablus, about 4,000 people poured into the streets chanting, "God is Great."

Still, even nations long at odds with the United States—Libya, Syria, Sudan and Iran—denounced the attacks.

"Irrespective of the conflict with America, it is a human duty to show sympathy with the American people, and be with them at these horrifying and awesome events, which are bound to awaken human conscience," Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi said.

Sudan's Foreign Ministry expressed its regret in a statement issued Wednesday and "reaffirmed its rejection of all kinds of violence."

Iranian President Mohammad Khatami "expressed deep regret and sympathy with the victims" and said "it is an international duty to try to undermine terrorism."

That contrasted sharply with the conservative Tehran Times newspaper, which juxtaposed a photo of the World Trade Center reduced to rubble with one of Mohammed al-Dura, the 12-year-old whose death in his father's arms during a gunbattle with Israeli troops in October turned him into a Palestinian symbol of martyrdom.

America is the terrorist, wrote an editorialist in Iraq, which has been crippled by U.S.-backed U.N. sanctions imposed to punish it for invading Kuwait in 1990.

Such anger only sporadically translates into armed attacks on the United States. Even attempts to hit America economically—such as boycotts against such icons as McDonald's restaurants or Coca-Cola—are short-lived, reflecting a love-hate element in Arabs' image of the United States.

By celebrating an attack on America, "we are violating our own cultural edicts," said Bishara, head of Kuwait's National Democratic Movement. "We are not Muslims anymore if we do this. There are norms and rules for fighting your enemy and getting your rights."

Many Muslim clerics agreed.

"The killing of innocent people is a despicable and heinous act that is accepted by neither religion nor human sensibility," said Grand Sheik Mohammed Sayed Tantawi of Cairo's Al-Azhar, Islam's oldest and most prominent religious institution.

Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri also criticized those who took joy in the terror attacks.

"They are not representing the feeling of the Arab world and the Islamic world," he told CNN.

Months or years from now, investigators may conclude that no Arab was behind the attacks. But Americans who watched Arabs applauding terrorism may nonetheless conclude they are the enemy, worried Egyptian political analyst Gehad Auda.

Auda recalled the 1991 Gulf War—when Palestinians rallied around Iraq—and its attempt to turn its invasion of Kuwait into a confrontation with Israel. The Palestinians ended up isolated.

"The Palestinians are making the same mistake in not controlling their emotions. Celebration at the moment of grief is wrong, uncalled for. And it's unwise," Auda said. "America before was undecided. Now America will be decided—for the Israelis."

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

A review of Gore Vidal's book on 9/11, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: How We Got to Be So Hated, sums up the key reasons for the hatred. From the LA Times, 5/12/02:

In Bin Laden's case, the terrorist attack was a response to a U.S. policy that one-sidedly backed Israel, satanized Saddam Hussein, defiled the Saudi holy land with American troops and demonstrated an "imperial disdain" for the Muslim world.

More on the subject

The anti-Israeli sentiment

Bombing Iraq: another source of anger

Repressive regimes: yet another source of anger

Deeper into the cultural clash

One waited in vain for any real discussion of how, after the most impressive period of global economic expansion in history, the world has come to be wracked by so much paralyzing global anger and hatred toward the U.S. Where were the voices analyzing how the miracle of "globalization" seems to have turned spaceship earth not into a global community of rising expectations, but into badly divided camps of winners and losers? Where was a convincing discussion of why Islamic fundamentalists are so hostile to all of our vaunted entrepreneurial notions of "progress," "winning," "being #1." Why the resentment of America unilaterally appointing itself as the world's peace keeper?

Orville Schell, "TV News Our Town Commons During Crisis," LA Times, 9/23/01

The civilized world finally appears willing to fight terrorism wherever it can be found. However, in this world war there are two fronts.

One front exists in dark alleyways, in secret safe-houses, in bomb-making laboratories, in terrorist training centers and in the technology and innovation of terrorism. The other front exists in the economies of the Third World that breed the people upon whom terrorist egomaniacs feed. If we forget this second front, we will not stop terrorism, because there will always be insane extremists who seek to lead people who have nowhere else to go. Human beings who have no choices; who, unlike Americans, have no true democracy; who have no jobs; who have no future; who have no homeland; or who are hungry will always be the feeding ground of these demented fanatics.

If we are to win this world war we must fight on both fronts or face the prospects of a continuing, growing threat to our civilization.

Kerry T. Nock, letter, LA Times, 9/19/01

I can't help but be struck by the juxtaposition of two stories on the Sept. 17 front page: Afghans face mass starvation, while Americans face recession. When one country had a per capita income in 1999 of $178 and the other a whopping $32,778, I feel lucky, of course, but also deeply ashamed. It is not only cruel but also foolhardy to ignore the economic inequity of our world. I'm sorry my portfolio is down, but I'm even sorrier for the poor refugees of this horrible situation.

Connie Tucker, letter, LA Times, 9/19/01

Anti-U.S. sentiments are common worldwide, not just limited to a few Islamic nations. And it is understandable. We make up about 5% of the world's population while using 30% of its resources. While millions of children and adults suffer from starvation worldwide, obesity is our health problem. Unless we change our lifestyle and learn to distribute resources, this world will continue to make many Osama bin Ladens.

Uday Devaskar MD, letter, LA Times, 9/25/01

What evokes greater horror—instantly snuffing out thousands of lives in this country to destroy centers of financial and military might or slowly snuffing out millions of lives around the world to maintain centers of financial and military might?

Carol Holst, letter, LA Times, 9/13/01

The planet rotates with a wobble because of an imbalance of wealth and power that fuels anti-American sentiment, and we respond with tax breaks for the wealthy and the mother of all bombs. My favorite line in the walk-up to war appeared in a story from Wall Street in which a broker was quoted on the rumored arrest of Osama bin Laden. Remember him?

"If they do get him," said the broker, "it's got to be good for a pop in equities and a decent pullback in bonds, say 10 basis points on the two-year yield. That's got the short-term crowd nervous."

Steve Lopez, "In This Case, the Simple Solution of War Is Simply the Wrong One," LA Times, 3/19/03

The LA Times published the following letter of mine, 9/20/01:

I suggest we carpet-bomb terrorist strongholds with Barbie dolls, cartoon videos and music CDs—the very cultural products our enemies are fighting tooth and nail against. After listening to the Barney song and "It's a Small World (After All)" a few dozen times, the terrorists will give up and beg us for mercy.

Follow the money

From the Guardian, 9/18/01:

It's All About Oil ... Again

If global conflict and ecological disaster are to be avoided, the west must end its reliance on oil, writes Mark Lynas

Saddam Hussein is right again. The US was "reaping the fruits of its crimes against humanity," the Butcher of Baghdad muttered darkly after hearing about the horrific destruction of the World Trade Centre. And it's true.

Difficult though it may be for the Americans to admit, they seem now to be suffering the consequences of nearly fifty years of neo-colonialist dominance in the Middle East. There is a way out of this mess, but it means that we in the rich world—and the United States in particular—need to face up to some uncomfortable realities.

As Said K Aburish shows in his groundbreaking 1997 book A Brutal Friendship, first the British and later the US secured control of the Middle East by supporting dictatorial client regimes against the wishes of their Arab peoples.

It was the British who gave a country to the obscure House of Saud, and established equally illegitimate monarchies in Jordan and Iraq—ironically with the justification that the new Hashemite kings were direct descendents of the Prophet Mohammed.

The policy of fostering friendly rulers was continued by the US after 1945, when it took over Britain's repressive role. The CIA helped to overthrow a populist and anti-western Iraqi government led by General Abden Karim Kassem in 1968. The agency even prepared lists for the coup leaders of people it thought should be butchered. One of the most enthusiastic killers, of course, was a young man called Saddam Hussein. Several thousand are thought to have died in the massacre.

Throughout the century, grassroots movements—occasionally flaring into open rebellion—challenged western supremacy from below. What is now described as "Islamic fundamentalism" is only the latest of these challenges, but it has become a serious threat to pro-US rulers in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Yasser Arafat's Palestine authority.

As Aburish puts it: "Because the west and its clients have succeeded in destroying all the secular movements in the Arab Middle East without making any attempts to solve the real problems of the region, Islam has emerged as the only force opposed to the western-Arab establishment hegemony."

And the results of this hegemony are plain—a total lack of democracy, massive corruption, and widening gaps between the haves and the have-nots. In Saudi Arabia, a steadfast US ally with over fifty billionaire princes, per capita income actually declined by half between 1982 and 1993. Is it any surprise therefore that the backstreets of Riyadh provide a fertile recruitment-ground for a new generation of activists against the west?

Osama bin Laden's al-Qaida organisation is only one of a plethora of Islamist groups opposed to US power in the Middle East, and his key aim of "pushing the American enemy out of the Holy Land" encapsulates the fusion of religious and anti-western sentiment.

As long as American troops continue to be stationed within spitting distance of the holiest Muslim sites of Mecca and Medina, potential suicide bombers from Hamas, al-Qaida and other extremist groups will remain convinced that their fast-track route to paradise is assured.

So why has the west spent a century subverting the legitimate aspirations of an entire people? The answer can be summed up in a single word: oil. The US imports nearly 9m barrels of crude oil per day, over 20% of it from the Persian Gulf states.

After Canada, Saudi Arabia is US's largest oil supplier, providing over 1.5m barrels a day to keep America's thirsty economy moving. US military might is the guarantor of steady oil supplies, and when this monopoly was threatened by Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1991, the renegade Saddam was quickly stamped on.

Now talk of war is again in the air, and the Middle East region (including the long-suffering Afghanistan) seems likely once more to be the main theatre of conflict. This time the fighting could be ugly and drawn-out, quite unlike the blitzkrieg against Saddam in the 1991 Gulf war.

In almost every oil-producing state, Islamist opposition movements are challenging US control in increasingly aggressive ways, and defeating them will require slaughter and repression on a massive scale.

Comment: These scenarios are a lot more realistic than the Bush propaganda about an attack on freedom or democracy. There's no plausible way terrorists can destroy the United States. But they can force us out of the Middle East—or, more realistically, force US-backed governments to reform.

More on the economic reasons for war

The Empire Needs New Clothes: "War isn't about oil, it's about maintaining the American lifestyle."

Globalization: exporting the American way

The bottom line?

More excerpts from Some People Push Back: On the Justice of Roosting Chickens by Ward Churchill:

A good case could be made that the war in which they were combatants has been waged more-or-less continuously by the "Christian West"—now proudly emblematized by the United States—against the "Islamic East" since the time of the First Crusade, about 1,000 years ago. More recently, one could argue that the war began when Lyndon Johnson first lent significant support to Israel's dispossession/displacement of Palestinians during the 1960s, or when George the Elder ordered "Desert Shield" in 1990, or at any of several points in between.

Had it not been for these evils, the counterattacks of September 11 would never have occurred. And unless "the world is rid of such evil," to lift a line from George Junior, September 11 may well end up looking like a lark.

See Understanding Islam for more on the cultural clash between the West and Islam.

More on why "they" don't like us

Why They Hate Us: "No, it's not our freedoms. Anti-Americanism isn't going away until the U.S. puts some fairness in its foreign policy."

This War and Racism: "[R]acial biases make the war process easier...."

Seeing Islam Through a Lens of U.S. Hubris: Our national mind-set may be leading us toward defeat, a CIA expert says.

U.S. Has Severe Image Problem in Much of Europe, Poll Finds: Opinions toward Bush and his foreign policy remain negative....

A Naked Bid to Redraw World Map: Sadly, Bush has made the U.S. the 21st century's first colonizer.

Why the U.S. Inspires Scorn: Other nations, and especially the Arab world, fear the start of an American empire.

How the World Sees Americans: "[T]he world's superpower...has a childlike understanding of everybody else."

America's exceptional values

Related links

Terrorism: "good" vs. "evil"

Culture and Comics Need Multicultural Perspective 2000

America's cultural mindset

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.

1967: Support for Israel in Middle East War and in subsequent conflicts with its Arab neighbors.

1967: Support for Israel in Middle East War and in subsequent conflicts with its Arab neighbors.