Although right-wingers who fear change will deny it, the US is profoundly conservative. From the LA Times, 9/26/04:

Although right-wingers who fear change will deny it, the US is profoundly conservative. From the LA Times, 9/26/04: Although right-wingers who fear change will deny it, the US is profoundly conservative. From the LA Times, 9/26/04:

Although right-wingers who fear change will deny it, the US is profoundly conservative. From the LA Times, 9/26/04:

America the Conservative

* Europe is in the 21st century, but we remain locked in the 18th

By Edward L. Glaeser

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Whether President Bush is reelected or Sen. John F. Kerry prevails, the United States will be the most conservative developed nation in the world. Its economy will remain the least regulated, its welfare state the smallest, its military the strongest and its citizens the most religious. According to data taken from the World Values Survey in the last decade, 60% of Americans believe that the poor are lazy (only 26% of Europeans share that view), and 30% believe that luck determines income (54% of Europeans say so). About 60% of Europeans say the poor are trapped, while only 29% of Americans believe they are. And roughly 30% of Europeans declare themselves to be left wing, but only 17% of Americans do.

Why is the U.S. such an exceptionally conservative nation?

It's tempting to think that American conservatism is the natural result of exceptional economic mobility in the country, but the odds of leaving poverty in Europe are higher than those in the United States, in part because European social democrats enacted national education policies that do a better job of looking after the poor than local schools in the U.S. Instead, American conservatism stems from political stability and ethnic heterogeneity.

The Constitution was designed with checks to protect private property and to ensure that change happens slowly. The U.S. elects its representatives by majority vote, which leads politicians to cater to the voter in the middle, not the poorest. By contrast, proportional representation in many European countries gives greater voice to politicians who stand for minority groups like the poor. In most European countries, proportional representation is also strongly related to spending on social programs.

The sharp separation of powers in the U.S., as the Federalist Papers predicted, has reduced the extension of government. Battles between Congress and the presidency — such as President Franklin D. Roosevelt's fights with the Senate in the late 1930s — have historically stymied the growth of the welfare state. The powerful, unelected Supreme Court has supported conservatism at many critical periods in our history. For example, in the late-19th century, it declared the income tax unconstitutional; in the 1930s, the court ruled that the New Deal was unlawful; and in 2000, it intervened to decide the presidential election. The nation's federalist structure, furthermore, limits states' welfare spending because they fear the flight of capital and wealthy residents.

One doesn't need to embrace Beardian conspiracy theories to believe that the Constitution was designed to limit the central government's ability to extract resources from wealthy citizens. As a result, it has succeeded in checking the rise of an American socialist state while all the larger countries in continental Europe have socialism-friendly political institutions.

It wasn't always so. At the start of the 20th century, the U.S. looked progressive compared with Europe's empires. The big difference between the U.S. and Europe is that the U.S. kept its 18th century Constitution, while most European countries discarded theirs. In a wave of revolutions and quasi-revolutionary general strikes, European countries, one by one, replaced their older conservative constitutions with ones often designed by socialist or labor leaders.

Some small nations introduced proportional representation before World War I in response to uprisings that threatened their governments' stability, but the war was a watershed for great powers like Germany, Russia and Austro-Hungary. These nations' armies had traditionally checked militant labor unrest, just as in the United States, but during World War I, mass mobilizations and steady demoralization broke the armies' will to fire on rioters. As the armies' policing power vanished, empires were upended by left-wing revolutions. The new constitutions of these countries were written by socialist leaders like Friedrich Ebert, who were determined to craft institutions, like proportional representation, that would entrench socialist power. France had a constitution drafted by a socialist-heavy group, but this had to wait until after its defeat in World War II.

By contrast, the U.S. has not lost a war on its home soil and thus has never faced the internal disruptions caused by such a collapse. The U.S. military and private armies, like Pinkerton's, have always been able to subdue agitators, such as the Homestead, Pa., strikers who faced off against Andrew Carnegie in 1892 and the jobless World War I veterans who marched to Washington in 1932 to ask for their bonus, and were dispersed — with swords drawn — by Army troops.

The nation's racial heterogeneity also partly explains its conservatism. U.S. heterogeneity sharply contrasts with the much greater homogeneity in Canada, Britain and continental Europe. People are much less likely to support income redistribution to people who are members of different racial or ethnic groups. Ethnic divisions make it easier for the enemies of welfare to vilify the poor, by making them seem like parasites who could be rich but prefer to live on the public dollar. The pro-redistribution populists were defeated in the South in the 1890s by politicians who stressed that populism would help blacks (which was true) and that blacks were dangerous criminals (which was not.) The enemies of Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society also employed racial messages that conveyed the idea that welfare recipients were dangerous outsiders who should not be helped. The sharp racial division that runs through American society makes it possible to castigate poor people in a way that would be impossible in a homogeneous nation like Sweden, where the poor look the same as everyone else.

Across countries, ethnic heterogeneity strongly predicts a smaller welfare state. The U.S. states with larger populations of blacks have historically been less generous to the poor (even controlling for state per capita income). Work by Erzo Luttmer, professor at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, shows that people who live around poor people of their own races say they want the government to spend more on welfare. But people who live around poor people of another race say they want the government to spend less on welfare. Sympathy for the poor appears to be muted when the poor are seen as outsiders.

Increased immigration to Europe is making those societies more heterogeneous, and we have already seen opponents of social welfare, such as Jean-Marie Le Pen in France, Joerg Haider in Austria and Pim Fortuyn in the Netherlands, use inflammatory anti-immigrant rhetoric to discredit generous welfare payments. We may like to believe that human beings are colorblind, but the reality is that American diversity has always made redistribution less popular here than in more ethnically and racially homogeneous places.

Edward L. Glaeser is a professor of economics at Harvard University, director of the Taubman Center for State and Local Government at the Kennedy School of Government, and author with Alberto Alesina, of "Fighting Poverty in the U.S. and Europe: A World of Difference."

A brief history of today's conservatism

White men have sought to dominate and rule every since they first came to America. The enemies they found or invented to justify their depredations included Indians, immigrants, and labor unions. They fear or hate any individuals who threaten their "individualism"—i.e., their right to do whatever they want, unfettered by rules and restrictions.

White men began losing their grip, literally and figuratively, when the culture wars blossomed in the 1960s. Vietnam was central to those wars, as was the civil rights movement. It's more correct to say the paramilitary culture reemerged in the '70s as a tougher, more aggressive response to these culture wars. If the fire hoses and attack dogs hadn't slowed down the liberals, they'd try to turn the culture wars into real wars.

A statesman might've found a way to heal the wounds of the '60s. Instead, we got Richard Nixon, who exacerbated the conflicts and crystallized the views of left and right.

From Oliver Stone's book review of The Arrogance of Power: The Secret Life of Richard Nixon by Anthony Summers. In the LA Times, (8/19/01):

It was through Richard Nixon that the modern Republican Party was reborn roughly 100 years after Lincoln—though probably not in the manner the patriarch would've approved. In putting himself above the party's interests in 1968 and again so egregiously in 1972, Nixon dismembered moderate Republicanism into what it has become today—a party of negative hardball politics, pious association with a Christian God, and the contradictions of wanting less government but more control of private lives, bodies, individual rights and new definitions of criminality and cultural and drug "wars"—the chilling effects of which, in their authoritarianism, have taken the Grand Old Party more in the direction of Savonarola than Eisenhower.

As Stone reports, Nixon set the tone for the modern Republican. He polarized politics as few before him had done. He made it okay to vilify one's opponents as vermin who must be routed or killed:

It appears now that Nixon never had any intention of "bringing us as a people together" as he promised in 1968. To the contrary, he deeply hated opposition in all forms, whether foreign leaders (Castro, Ho Chi Minh), politicians (all the Kennedys, George Wallace), intellectuals (Alger Hiss, Daniel Ellsberg), celebrities (Jane Fonda) or the Chicago Seven, all of whom he erroneously thought were Jews. This is no passive Nixon but a man at the head of a criminal enterprise not unlike the Mafia, dead set on getting even with those who made his life so painful.

Nixon was the apotheosis of hatred for an establishment that tried to achieve a country "of the people, by the people, for the people." He exposed the conservative mindset that said a white, male, Christian elite should rule. Conservatives had always harbored feelings of macho superiority—a dislike of anyone they deemed inferior (women, minorities, non-Christians, gays, etc.)—but Nixon made them public:

There is plenty here of classic gangster dialogue, replete with profanity and ethnic slurs, of which the following examples are among the more moderate: Of Italians: "They're not like us ... they smell different, they look different ... you can't find one that's honest ..." The IRS was "full of Jews" .... "Most Jews are disloyal" .... "You can't trust the bastards. They turn on you." On Robert Kennedy: "Why does Bobby get to be so mean, and I have to be so nice?" His Cabinet, Henry Kissinger and almost everyone close to him are at one point or another an "idiot," "moron," "jerk," "pansy," "fag," "ratbastard," "jewbastard," "viper in my bosom," "off the reservation."

Interesting that Nixon compared Jews and Italians with gays, idiots, rats, vipers, and especially Indians (people who come from reservations). Indians are the quintessential outsiders to Americans, the ultimate "other." Washington compared them to "wolves and beasts" and Jefferson called them "merciless...savages" in the Declaration of Independence. Not much has changed in 200 years.

Nixon's Southern strategy

How did Nixon turn the Republican Party into a stronghold of extremist ideology, of pseudo-Christianity and pseudo-patriotism, of white-male supremacy? He pandered to the regions, especially the South, where these attitudes were dominant. In an article titled "For Howard Dean to Win, He'll Have to Beat Nixon," Mark Kurlansky explains. From the LA Times, 12/29/03:

Nixon, always known more as an opportunist than an ideologue, assessed the political landscape when he ran for president in 1968, a time when Republicans had lost every presidential election since the Depression, except for two by Dwight D. Eisenhower. Like Dean today, he asked why are we losing and how can that be changed?

Nixon saw his opportunity in the decline of the great civil rights movement and the killing of Martin Luther King Jr. He judged that the South, a solid Democratic bloc that had never forgiven Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans for the Emancipation Proclamation, was furious about 10 years of civil rights progress and was ready to turn on the Democrats, who had received faithful Southern support since before the Civil War. In the end, Nixon defeated the Democrats not because of their worst disaster, Vietnam, but because of their greatest accomplishment, civil rights.

Nixon picked a Southern governor, Spiro T. Agnew, as his running mate. After he won, writes Kurlansky, "he began to attack the Supreme Court, attempting to destroy liberal judges and replace them with judges preferably from the South with anti-civil rights records." The Southernization of the GOP, and the nation, was on.

From Impossible, Ridiculous, Repugnant by Bob Herbert. In the NY Times, 10/6/05:

Listen to the late Lee Atwater in a 1981 interview explaining the evolution of the G.O.P.'s Southern strategy:

"You start out in 1954 by saying, 'Nigger, nigger, nigger.' By 1968 you can't say 'nigger' -- that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states' rights and all that stuff. You're getting so abstract now [that] you're talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you're talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites.

"And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I'm not saying that. But I'm saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me -- because obviously sitting around saying, 'We want to cut this,' is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than 'Nigger, nigger.' "

Atwater, who would manage George H. W. Bush's successful run for the presidency in 1988 (the Willie Horton campaign) and then serve as national party chairman, was talking with Alexander P. Lamis, a political-science professor at Case Western Reserve University. Mr. Lamis quoted Atwater in the book "Southern Politics in the 1990's."

The truth is that there was very little that was subconscious about the G.O.P.'s relentless appeal to racist whites. Tired of losing elections, it saw an opportunity to renew itself by opening its arms wide to white voters who could never forgive the Democratic Party for its support of civil rights and voting rights for blacks.

The payoff has been huge. Just as the Democratic Party would have been crippled in the old days without the support of the segregationist South, today's Republicans would have only a fraction of their current political power without the near-solid support of voters who are hostile to blacks.

When Democrats revolted against racism, the G.O.P. rallied to its banner.

Ronald Reagan, the G.O.P.'s biggest hero, opposed both the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of the mid-1960's. And he began his general election campaign in 1980 with a powerfully symbolic appearance in Philadelphia, Miss., where three young civil rights workers were murdered in the summer of 1964. He drove the crowd wild when he declared: "I believe in states' rights."

From "An Empty Apology" by Bob Herbert. In the NY Times, 7/18/05:

The important thing to keep in mind was how deliberate and pernicious the strategy was. Last month a jury in Philadelphia, Miss., convicted an 80-year-old man, Edgar Ray Killen, of manslaughter in the slaying of three civil rights workers -- Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney -- in the summer of 1964. It was a crime that made much of the nation tremble, and revolted anyone with a true sense of justice.

So what did Ronald Reagan do in his first run for the presidency, 16 years after the murder, in the summer of 1980? He chose the site of the murders, Philadelphia, Miss., as the perfect place to send an important symbolic message. Mr. Reagan kicked off his general election campaign at the Neshoba County Fair in Philadelphia, an annual gathering that was famous for its diatribes by segregationist politicians. His message: "I believe in states' rights."

Reagan the race-baiter

From Paul Krugman's column in the NY Times, 11/19/07:

By PAUL KRUGMAN

Published: November 19, 2007

Over the past few weeks there have been a number of commentaries about Ronald Reagan's legacy, specifically about whether he exploited the white backlash against the civil rights movement.

The controversy unfortunately obscures the larger point, which should be undeniable: the central role of this backlash in the rise of the modern conservative movement.

The centrality of race — and, in particular, of the switch of Southern whites from overwhelming support of Democrats to overwhelming support of Republicans — is obvious from voting data.

For example, everyone knows that white men have turned away from the Democrats over God, guns, national security and so on. But what everyone knows isn't true once you exclude the South from the picture. As the political scientist Larry Bartels points out, in the 1952 presidential election 40 percent of non-Southern white men voted Democratic; in 2004, that figure was virtually unchanged, at 39 percent.

More than 40 years have passed since the Voting Rights Act, which Reagan described in 1980 as "humiliating to the South." Yet Southern white voting behavior remains distinctive. Democrats decisively won the popular vote in last year's House elections, but Southern whites voted Republican by almost two to one.

The G.O.P.'s own leaders admit that the great Southern white shift was the result of a deliberate political strategy. "Some Republicans gave up on winning the African-American vote, looking the other way or trying to benefit politically from racial polarization." So declared Ken Mehlman, the former chairman of the Republican National Committee, speaking in 2005.

And Ronald Reagan was among the "some" who tried to benefit from racial polarization.

True, he never used explicit racial rhetoric. Neither did Richard Nixon. As Thomas and Mary Edsall put it in their classic 1991 book, "Chain Reaction: The impact of race, rights and taxes on American politics," "Reagan paralleled Nixon's success in constructing a politics and a strategy of governing that attacked policies targeted toward blacks and other minorities without reference to race — a conservative politics that had the effect of polarizing the electorate along racial lines."

Thus, Reagan repeatedly told the bogus story of the Cadillac-driving welfare queen — a gross exaggeration of a minor case of welfare fraud. He never mentioned the woman's race, but he didn't have to.

There are many other examples of Reagan's tacit race-baiting in the historical record. My colleague Bob Herbert described some of these examples in a recent column. Here's one he didn't mention: During the 1976 campaign Reagan often talked about how upset workers must be to see an able-bodied man using food stamps at the grocery store. In the South — but not in the North — the food-stamp user became a "strapping young buck" buying T-bone steaks.

Now, about the Philadelphia story: in December 1979 the Republican national committeeman from Mississippi wrote a letter urging that the party's nominee speak at the Neshoba Country Fair, just outside the town where three civil rights workers had been murdered in 1964. It would, he wrote, help win over "George Wallace inclined voters."

Sure enough, Reagan appeared, and declared his support for states' rights — which everyone took to be a coded declaration of support for segregationist sentiments.

Reagan's defenders protest furiously that he wasn't personally bigoted. So what? We're talking about his political strategy. His personal beliefs are irrelevant.

Why does this history matter now? Because it tells why the vision of a permanent conservative majority, so widely accepted a few years ago, is wrong.

The point is that we have become a more diverse and less racist country over time. The "macaca" incident, in which Senator George Allen's use of a racial insult led to his election defeat, epitomized the way in which America has changed for the better.

And because conservative ascendancy has depended so crucially on the racial backlash — a close look at voting data shows that religion and "values" issues have been far less important — I believe that the declining power of that backlash changes everything.

Can anti-immigrant rhetoric replace old-fashioned racial politics? No, because it mobilizes the same shrinking pool of whites — and alienates the growing number of Latino voters.

Now, maybe I'm wrong about all of this. But we should be able to discuss the role of race in American politics honestly. We shouldn't avert our gaze because we're unwilling to tarnish Ronald Reagan's image.

Since Reagan, many Republican leaders—Newt Gingrich, Jesse Helms, Tom DeLay, Dick Armey, Trent Lott—have come from and pandered to the South. From Paul Krugman's column in the NY Times, 9/24/07:

[T]he reality is that things haven't changed nearly as much as people think. Racial tension, especially in the South, has never gone away, and has never stopped being important. And race remains one of the defining factors in modern American politics.

Consider voting in last year's Congressional elections. Republicans, as President Bush conceded, received a "thumping," with almost every major demographic group turning against them. The one big exception was Southern whites, 62 percent of whom voted Republican in House races.

And yes, Southern white exceptionalism is about race, much more than it is about moral values, religion, support for the military or other explanations sometimes offered. There's a large statistical literature on the subject, whose conclusion is summed up by the political scientist Thomas F. Schaller in his book "Whistling Past Dixie": "Despite the best efforts of Republican spinmeisters to depict American conservatism as a nonracial phenomenon, the partisan impact of racial attitudes in the South is stronger today than in the past."

Republican politicians, who understand quite well that the G.O.P.'s national success since the 1970s owes everything to the partisan switch of Southern whites, have tacitly acknowledged this reality. Since the days of Gerald Ford, just about every Republican presidential campaign has included some symbolic gesture of approval for good old-fashioned racism.

Thus Ronald Reagan, who began his political career by campaigning against California's Fair Housing Act, started his 1980 campaign with a speech supporting states' rights delivered just outside Philadelphia, Miss., where three civil rights workers were murdered. In 2000, Mr. Bush made a pilgrimage to Bob Jones University, famed at the time for its ban on interracial dating.

And all four leading Republican candidates for the 2008 nomination have turned down an invitation to a debate on minority issues scheduled to air on PBS this week.

Naturally, George W. Bush is the apotheosis of this trend.

Hurricane Katrina showed how Bush is continuing the Nixon/Reagan tactic of dividing the nation by race. He has wielded government as a weapon to promote white, Christian interests at the expense of minorities. From Paul Krugman's column in the NY Times, 9/19/05:

[I]n a larger sense, the administration's lethally inept response to Hurricane Katrina had a lot to do with race. For race is the biggest reason the United States, uniquely among advanced countries, is ruled by a political movement that is hostile to the idea of helping citizens in need.

Race, after all, was central to the emergence of a Republican majority: essentially, the South switched sides after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Today, states that had slavery in 1860 are much more likely to vote Republican than states that didn't.

And who can honestly deny that race is a major reason America treats its poor more harshly than any other advanced country? To put it crudely: a middle-class European, thinking about the poor, says to himself, "There but for the grace of God go I." A middle-class American is all too likely to think, perhaps without admitting it to himself, "Why should I be taxed to support those people?"

Above all, race-based hostility to the idea of helping the poor created an environment in which a political movement hostile to government aid in general could flourish.

By all accounts Ronald Reagan, who declared in his Inaugural Address that "government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem," wasn't personally racist. But he repeatedly used a bogus tale about a Cadillac-driving Chicago "welfare queen" to bash big government. And he launched his 1980 campaign with a pro-states'-rights speech in Philadelphia, Miss., a small town whose only claim to fame was the 1964 murder of three civil rights workers.

Under George W. Bush -- who, like Mr. Reagan, isn't personally racist but relies on the support of racists -- the anti-government right has reached a new pinnacle of power. And the incompetent response to Katrina was the direct result of his political philosophy. When an administration doesn't believe in an agency's mission, the agency quickly loses its ability to perform that mission.

The cult(ure) of Christianity

In The Fundamental President (Indian Country Today, 12/30/03), John C. Mohawk lays out the connection between Bush (and, by implication, other right-wing Republicans) and the Southern cult(ure) of Christianity:

Religion, and specifically Southern Protestant fundamentalism, is the dominant cultural reality in the Bush White House and in the process which has led to war. Although George W. Bush is nominally a Methodist, he has pandered shamelessly to the religious right and many of his views are consistent with those of Protestant fundamentalist extremists. He has confirmed such views more than once, and is on record stating his belief that non-Christians can never go to heaven. This is a statement with enormous implications that he is not president to all Americans but to a minority, albeit a sizeable minority. The religious culture he comes from is even more narrow than that, defining only born-again Christians as true to the faith and therefore eligible for admission to heaven.

Mr. Bush is steeped in the culture of West Texas, a culture with many of the characteristics of the Old South. It is tinged with a history of racism, has a strong anti-environmentalist ethos, wallows in crony capitalism, exalts in jingoistic militarism, and has an anti-public education and anti-welfare bias. The president has discovered that it is not productive to embrace all these ideologies publicly, but he has set into motion an agenda which makes the radical religious right as happy as it has been in generations.

It is not difficult to understand how the Old South came to be the way it is. In the 19th century, America was alone among industrialized nations to tolerate slavery. In the South, slave labor not only drove agricultural profits prior to the industrial revolution in agriculture, it also set the tone of the culture. People who depend on beatings and other forms of torture to keep their laborers in line and who casually rape and abuse the women they "own" have good reason to sleep with a gun under their pillow for fear that their "property" might rise from their hovels and kill them in their sleep. It helps to explain America's love affair with firearms. Although slavery was outlawed in 1863, significant elements of the culture which spawned it are thriving.

The South is the most militaristic area of the country and a higher percentage of its population is in the military than any other population in the country. The U.S. has never entered a war that the South didn't like, including the War of 1812, the Mexican War, numerous Indian wars, their part of the Civil War, the preemptive Philippines War, and so forth. Southern white Protestant males are the most violent population in America and possess the highest murder rate. Despite intense religiosity and lots of rhetoric around "family values," that population also has the highest divorce rate in the country.

Again, Bush has finished what Nixon started. Nixon was less successful than Bush because he still had to deal with powerful Democratic and democratic forces. Liberals were ascendant then, not in full retreat like they are now.

Watergate, in which liberals seemed to bring down Nixon and other high officials—the keepers of conservative authority—only fueled the feeling that the two sides were at war. So did the energy crisis and the hostages in Iran. Liberals didn't create these problems, but the seemed to tolerate them by not being "tough" enough to solve them.

Conservatives couldn't stomach "losing" because it impugned their circular philosophy: America was great because it won and won because it was great. If America could lose—in Vietnam, in Watergate, in the hostage crisis, their worldview would shatter. Rather than pick up the pieces and use them to forge a more compassionate, Christ-like outlook, they manned the barricades.

Nixon/Ford to Carter to Reagan

Sick of Tricky Dick and Gerald Ford's pardon of same, Americans elected Jimmy Carter to restore morality to the White House. But Carter proved to be mediocre in other ways and circumstances did him in. The country longed for a savior, someone who could vanquish the evildoers (Commies, Arabs, or whoever) and restore America to its rightful position of glory. Nixon had failed to end the national nightmare and restore the dream, but the desire to do so still beat in American hearts.

Ronald Reagan was the culmination of these longings. Inheriting the Goldwater mantle, Ronnie advocated and ran on a return to tradition. Traditional Americans had suffered enough "losses" that they finally mustered the strength to elect a cowboy president. Reagan, they believed, would let them stand tall and be men again (even if they were women).

The new warrior hero wasn't really new. He simply reemerged after the 1960s, just as conservatives reemerged. He was essentially a bigger, badder version of John Wayne, America's no. 1 icon. He was the cultural warrior Nixon only aspired to be.

Americans have always idolized the lone gunslinger type of hero. Dirty Harry and Rambo are just recent incarnations of the cowboy archetype. These heroes resonate because they represent how Americans see themselves.

Stoked by Reagan's me-first philosophy, the conservative culture and its paramilitary fringe flourished for a few years. Contrary to the assertion above, it didn't just "fade" because the Soviet Union collapsed. Rather, it wilted in concert with the Reagan/Bush era.

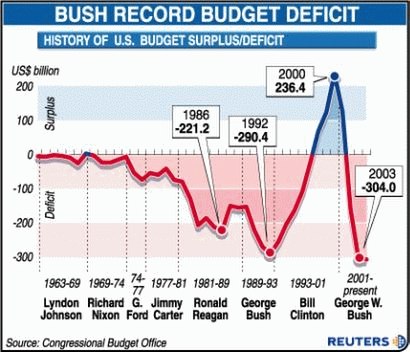

Given a chance to restore America, Reagan's cowboy approach proved a failure overall. Supply-side economics caused massive deficits, S&L failures, and ultimately another recession. Negative social indicators such as crime rates, unwed pregnancies, and drug use peaked. The environment took a header as ozone holes appeared over Antarctica. Dictators who trampled America's values earned praise. Racism, poverty, and AIDS were ignored.

Militarily, we couldn't defeat anyone tougher than Grenada without making deals with the Ayatollah or shooting down innocent airliners. We couldn't defeat the Soviet Union—they "defeated" themselves through a nonviolent revolution. The Pope's calls for social justice reverberated more strongly than Reagan's "just say no" blandishments.

George Bush the senior showed that Reagan's successes depended on Reagan's charm and rhetorical skills, not on any virtue in the conservatives' positions. Bush frittered away Reagan's momentum and sent the economy into another recession. The pendulum was about to swing again.

Reagan/Bush to Clinton

Because selfishness wasn't all it was cracked up to be as a social ideology, Americans elected Bill Clinton to provide a "third way." Unfortunately, he acted too liberal his first year—universal health care, gays in the military—and squandered ais opportunity. Conservatives licked their lips and moved in for the kill.

Their response was the "Republican Revolution" of 1994, the "tidal wave" led by drips like Newt Gingrich and Rush Limbaugh. It was another cultural swing in miniature. Instead of 15-20 years of liberalism followed by 12 years of conservatism, it was 15-20 months of liberalism followed by 12 months of conservatism. (Roughly, of course.)

Neo-conservatives like Gingrich weren't necessarily paramilitarists, but they shared many values with the McVeighs of America. Primary among them were a hatred of government and "welfare" and a love of guns and money. Freedom meant freeing everyone to engage in a free-for-all. (See "anarchy," above.)

Neo-cons were basically insider versions of McVeigh's outsider. They were wealthy and educated while McVeigh was poor and uneducated. But both conceived themselves as patriotic revolutionaries who'd return America to the Founding Fathers' original philosophy—which they misunderstood, since the Founders were the liberals of their time and favored a central government.

By this time, the deevolution of the Republican Party was almost complete. As Garrison Keillor wrote in We're Not in Lake Wobegon Anymore (8/26/04):

Something has gone seriously haywire with the Republican Party. Once, it was the party of pragmatic Main Street businessmen in steel-rimmed spectacles who decried profligacy and waste, were devoted to their communities and supported the sort of prosperity that raises all ships. They were good-hearted people who vanquished the gnarlier elements of their party, the paranoid Roosevelt-haters, the flat Earthers and Prohibitionists, the antipapist antiforeigner element. The genial Eisenhower was their man, a genuine American hero of D-Day, who made it OK for reasonable people to vote Republican. He brought the Korean War to a stalemate, produced the Interstate Highway System, declined to rescue the French colonial army in Vietnam, and gave us a period of peace and prosperity, in which (oddly) American arts and letters flourished and higher education burgeoned -- and there was a degree of plain decency in the country. Fifties Republicans were giants compared to today's. Richard Nixon was the last Republican leader to feel a Christian obligation toward the poor.

In the years between Nixon and Newt Gingrich, the party migrated southward down the Twisting Trail of Rhetoric and sneered at the idea of public service and became the Scourge of Liberalism, the Great Crusade Against the Sixties, the Death Star of Government, a gang of pirates that diverted and fascinated the media by their sheer chutzpah, such as the misty-eyed flag-waving of Ronald Reagan who, while George McGovern flew bombers in World War II, took a pass and made training films in Long Beach. The Nixon moderate vanished like the passenger pigeon, purged by a legion of angry white men who rose to power on pure punk politics. "Bipartisanship is another term for date rape," says Grover Norquist, the Sid Vicious of the GOP. "I don't want to abolish government. I simply want to reduce it to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub." The boy has Oedipal problems and government is his daddy.

The party of Lincoln and Liberty was transmogrified into the party of hairy-backed swamp developers and corporate shills, faith-based economists, fundamentalist bullies with Bibles, Christians of convenience, freelance racists, misanthropic frat boys, shrieking midgets of AM radio, tax cheats, nihilists in golf pants, brownshirts in pinstripes, sweatshop tycoons, hacks, fakirs, aggressive dorks, Lamborghini libertarians, people who believe Neil Armstrong's moonwalk was filmed in Roswell, New Mexico, little honkers out to diminish the rest of us, Newt's evil spawn and their Etch-A-Sketch president, a dull and rigid man suspicious of the free flow of information and of secular institutions, whose philosophy is a jumble of badly sutured body parts trying to walk. Republicans: The No.1 reason the rest of the world thinks we're deaf, dumb and dangerous.

Clinton/Gore to Bush

Clinton's real and perceived excesses disillusioned and exhausted the American public. They had turned to Clinton as they turned to Carter, to save them from conservative greed and corruption. Both Democrats promised more than they delivered, thus letting people down.

That gave George W. Bush a chance to defeat Al Gore. With Clinton's economic record, the election should've been a slum-dunk for Gore. But Gore's woodenness couldn't overcome Bush's lies about being a "compassionate conservative" and a "uniter, not a divider." Nor could they overcome a Supreme Court bent on restoring the elite to power.

As the new millennium unfolds, the battle lines remain drawn. King George is standing in for cowboy Reagan (you can call Dubya "Reagan Lite") and terrorism is standing in for Communism. Once again an evil opponent requires a massive military buildup, a limit on civil rights and government information, and the dismissal of "nonessential" concerns such as education, health, and the environment. It's 1984 all over again, in more ways than one, as the culture wars continue.

Conservatives have no compass

Another pundit uses the war on Iraq to argue a similar point:

Wednesday, March 16, 2005

COMMENTARY: Americans have lost their philosophical compasses

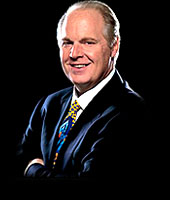

Rush Limbaugh has had a good run. However, after 17 years as a syndicated radio talk-show host, he has lost his philosophical compass. He has morphed from a thoughtful advocate for conservatism to becoming a mouthpiece for the current administration. In the 54-year-old Limbaugh's eyes, President Bush can do no wrong, even when he strays from traditional conservative values.

In other words, Limbaugh is a company man; or, more precisely, a party man, blindly backing the Republican Party. This intellectual sloth fosters hypocritical ideas and shifting opinions, much like we saw in President Clinton.

Perhaps Limbaugh's personal problems — divorce, legal troubles, hearing loss, an addiction to pain killers, just to name a few — are distracting enough to have tainted his thinking in recent years.

Nowhere is this more evident than in his blind support for the Iraq War.

Limbaugh, who refuses to come clean on how he avoided the draft during the Vietnam War, has been an outspoken advocate of sending young American troops to Iraq to die in a war being fought for no apparent reason. The Bush administration's justifications for the war that has killed more than 1,500 Americans is in constant flux, shifting more often than the sands of the Arabian desert.

While Limbaugh supports Bush's deadly misadventure in Iraq, he was an avid opponent, and rightly so, of Clinton's little war in Kosovo. Limbaugh also was opposed, again rightly so, to Clinton's stationing of peacekeeping troops in Bosnia.

Yet, he unabashedly supports the war in Iraq.

Why?

Simply because it is being executed by his party and not the Democrats.

The biggest sin in the world of punditry is inconsistency and Limbaugh has been inconsistent when it comes to the use of military force.

The reason is that Limbaugh is not a conservative pundit, but rather a Republican pundit.

In reality, his so-called Institute of Conservative Studies should really be referred to as the Institute of Republican Party Studies. After all, if he were truly a conservative, rather than a Republican, he would be criticizing many of President Bush's programs, including the No Child Left Behind Act and the Patriot Act.

Additionally, Bush has grown discretionary spending — defense, homeland security and other non-defense programs — more every year of his administration than Clinton ever did. Between 2001 and 2004, discretionary spending has increased 38 percent and overall government spending has increased 26 percent, according to the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank.

Where is Limbaugh's conservative outrage at that? A true conservative would be appalled at such blatant disregard for the core conservative concept of limited government.

I don't mean to turn this into an anti-Limbaugh rant. Actually, I still listen to him and agree with a large part of what he has to say. When it comes to rationalizing the president's actions, no one can do it with more imagination and originality than Limbaugh.

However, he is a symptom of a larger problem in this country. Too many Americans do not have a philosophical compass. They either formulate their opinions based on their party affiliation or simply by expediency. Either way, they lack consistency from issue to issue, often taking the intellectual path of least resistance, afraid to publicly criticize members of their own party.

For example, a person cannot be opposed to government spending in one case, but support it in another simply because it becomes beneficial to his or her community. It is a specious argument for such a person to support government spending by arguing that it merely brings home federal tax dollars that would otherwise be spent elsewhere.

Perhaps the age of principled stands in governing and public debate are long gone, replaced by an era of superficial and constantly changing opinion dressed in pleasant words so as not to offend anyone.

In that regard, Limbaugh does not disappoint. He still knows how to overturn the occasional apple cart, provided they are Democrat apples. While he may be intellectually dishonest in his conservative claims, at least Limbaugh is entertaining.

Perhaps that is the most one can expect in a nation where superficial partisan bickering has become more important than intellectual reasoning based on deeply held beliefs.

What a shame.

Thomas J. Lucente Jr.

Conservatism = Machiavellism

So today's conservatism isn't about obtaining the "proper" outcome on issues, then leaving people alone. It's about controlling people's behavior, putting them in their place, keeping them in thrall. Conservatives will lie, exaggerate, or flip-flop on the issues—whatever it takes to get their way.

A commentator explains how right-wing extremists operate when they're in power. From the LA Times, 10/24/04:

POLITICS

Karl Rove: America's Mullah

* This election is about Rovism, and the outcome threatens to transform the U.S. into an ironfisted theocracy.

By Neal Gabler

Neal Gabler, a senior fellow at the Norman Lear Center at USC Annenberg, is author of "Life the Movie: How Entertainment Conquered Reality."

Even now, after Sen. John F. Kerry handily won his three debates with President Bush and after most polls show a dead heat, his supporters seem downbeat. Why? They believe that Karl Rove, Bush's top political operative, cannot be beaten. Rove the Impaler will do whatever it takes — anything — to make certain that Bush wins. This isn't just typical Democratic pessimism. It has been the master narrative of the 2004 presidential campaign in the mainstream media. Attacks on Kerry come and go — flip-flopper, Swift boats, Massachusetts liberal — but one constant remains, Rove, and everyone takes it for granted that he knows how to game the system.

Rove, however, is more than a political sharpie with a bulging bag of dirty tricks. His campaign shenanigans — past and future — go to the heart of what this election is about.

Democrats will tell you it is a referendum on Bush's incompetence or on his extremist right-wing agenda. Republicans will tell you it's about conservatism versus liberalism or who can better protect us from terrorists. They are both wrong. This election is about Rovism — the insinuation of Rove's electoral tactics into the conduct of the presidency and the fabric of the government. It's not an overstatement to say that on Nov. 2, the fate of traditional American democracy will hang in the balance.

Rovism is not simply a function of Rove the political conniver sitting in the counsels of power and making decisions, though he does. No recent presidency has put policy in the service of politics as has Bush's. Because tactics can change institutions, Rovism is much more. It is a philosophy and practice of governing that pervades the administration and even extends to the Republican-controlled Congress. As Robert Berdahl, chancellor of UC Berkeley, has said of Bush's foreign policy, a subset of Rovism, it constitutes a fundamental change in "the fabric of constitutional government as we have known it in this country."

Rovism begins, as one might suspect from the most merciless of political consiglieres, with Machiavelli's rule of force: "A prince is respected when he is either a true friend or a downright enemy." No administration since Warren Harding's has rewarded its friends so lavishly, and none has been as willing to bully anyone who strays from its message.

There is no dissent in the Rove White House without reprisal.

Army Chief of Staff Gen. Eric K. Shinseki was retired after he disagreed with Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld's transformation of the Army and then testified that invading Iraq would require a U.S. deployment of 200,000 soldiers.

Chief Medicare actuary Richard Foster was threatened with termination if he revealed before the vote that the administration had seriously misrepresented the cost of its proposed prescription drug plan to get it through Congress.

Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill was peremptorily fired for questioning the wisdom of the administration's tax cuts, and former U.S. administrator L. Paul Bremer III felt compelled to recant his statement that there were insufficient troops in Iraq.

Even accounting for the strong-arm tactics of Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon, this isn't government as we have known it. This is the Sopranos in the White House: "Cross us and you're road kill."

Naturally, the administration's treatment of the opposition is worse. Rove's mentor, political advisor Lee Atwater, has been quoted as saying: "What you do is rip the bark off liberals." That's how Bush has governed. There is a feeling, perhaps best expressed by Georgia Democratic Sen. Zell Miller's keynote address at the Republican convention, that anyone who has the temerity to question the president is undermining the country. At times, Miller came close to calling Democrats traitors for putting up a presidential candidate.

This may be standard campaign rhetoric. But it's one thing to excoriate your opponents in a campaign, and quite another to continue berating them after the votes are counted.

Rovism regards any form of compromise as weakness. Politics isn't a bus we all board together, it's a steamroller.

No recent administration has made less effort to reach across the aisle, and thanks to Rovism, the Republican majority in Congress often operates on a rule of exclusion. Republicans blocked Democrats from participating in the bill-drafting sessions on energy, prescription drugs and intelligence reform in the House. As Rep. George Miller (D-Martinez) told the New Yorker, "They don't consult with the nations of the world, and they don't consult with Congress, especially the Democrats in Congress. They can do it all themselves."

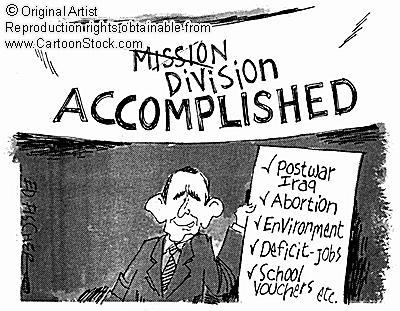

Bush entered office promising to be a "uniter, not a divider." But Rovism is not about uniting. What Rove quickly grasped is that it's easier and more efficacious to exploit the cultural and social divide than to look for common ground. No recent administration has as eagerly played wedge issues — gay marriage, abortion, stem cell research, faith-based initiatives — to keep the nation roiling, in the pure Rovian belief that the president's conservative supporters will always be angrier and more energized than his opponents. Division, then, is not a side effect of policy; in Rovism, it is the purpose of policy.

The lack of political compromise has its correlate in the administration's stubborn insistence that it doesn't have to compromise with facts. All politicians operate within an Orwellian nimbus where words don't mean what they normally mean, but Rovism posits that there is no objective, verifiable reality at all. Reality is what you say it is, which explains why Bush can claim that postwar Iraq is going swimmingly or that a so-so economy is soaring. As one administration official told reporter Ron Suskind, "We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality…. We're history's actors."

When neither dissent nor facts are recognized as constraining forces, one is infallible, which is the sum and foundation of Rovism. Cleverly invoking the power of faith to protect itself from accusations of stubbornness and insularity, this administration entertains no doubt, no adjustment, no negotiation, no competing point of view. As such, it eschews the essence of the American political system: flexibility and compromise.

In Rovism, toughness is the only virtue. The mere appearance of change is intolerable, which is why Bush apparently can't admit ever making a mistake. As Machiavelli put it, the prince must show that "his judgments are irrevocable."

Rovism is certainly not without its appeal. As political theorist Sheldon Wolin once characterized Machiavellian government, it promises the "economy of politics." Americans love toughness. They love swagger. In a world of complexity and uncertainty, especially after Sept. 11, they love the idea of a man who doesn't need anyone else. They even love the sense of mission, regardless of its wisdom.

These values run deep in the American soul, and Rovism consciously taps them. But they are not democratic. Unwavering discipline, demonization of foes, disdain for reality and a personal sense of infallibility based on faith are the stuff of a theocracy — the president as pope or mullah and policy as religious warfare.

Boiled down, Rovism is government by jihadis in the grip of unshakable self-righteousness — ironically the force the administration says it is fighting. It imposes rather than proposes.

Rovism surreptitiously and profoundly changes our form of government, a government that has been, since its founding by children of the Enlightenment, open, accommodating, moderate and generally reasonable.

All administrations try to work the system to their advantage, and some, like Nixon's, attempt to circumvent the system altogether. Rove and Bush neither use nor circumvent, which would require keeping the system intact. They instead are reconfiguring the system in extra-constitutional, theocratic terms.

The idea of the United States as an ironfisted theocracy is terrifying, and it should give everyone pause. This time, it's not about policy. This time, for the first time, it's about the nature of American government.

We all have reason to be very, very afraid.

To be swayed by Machiavellian manipulators—whether it's Karl Rove, Rush Limbaugh and other purveyors of "Faux News," or David Duke and other white supremacists—conservatives can't ask too many questions. They have to turn off their minds and stop processing information, which they do quite well. This is why you often see them marching in lockstep like good little soldiers.

In a Jan. 2005 entry in his blog, David Corn examines why Republicans and other conservatives are easily led astray:

Are Most Republicans Sheep?

I try not to denigrate entire groups of people—like the French, professional wrestling fans or even telephone solicitors. Actually, the French were quite nice to me on a recent trip to Paris, and I find it difficult not to condemn all telephone solicitors to the most unpleasant nooks of hell. But I may have to break this rule altogether for Republicans. I'm starting to wonder: do Republicans know how to process facts and think for themselves? This fall—thanks to a survey conducted by the University of Maryland's Program on International Policy Attitudes—we learned that 72 percent of Republicans believe Iraq had actual weapons of mass destruction, even after it had been widely reported that the Bush administration's own WMD hunters had concluded that Iraq had absolutely no WMD or active WMD programs in the years prior to the invasion. Three-quarters of Republicans also said that Saddam Hussein had provided substantial assistance to al Qaeda. Which meant they had either ignored or dismissed the conclusions of the independent 9/11 commission and the CIA. Both found no evidence of any operational alliance between Iraq and Osama bin Laden's murderous outfit.

Now the Pew Research Center reports that 66 percent of Republicans say "we all should be willing to fight for our country whether it is right or wrong." Think about it. That means Republicans believe it is perfectly fine to sacrifice their fellow citizens (those who volunteer for military service) and to kill people overseas—even innocent civilians (since accidents do happen in war)—for a mistake. In other words—or is it the same words?—two-thirds of Republicans are willing to see others die for no good reason.

Shouldn't Americans, as well as the citizens of all lands, ask questions (even if politely) whenever their leaders tell them, "It's time for you to kill and die"? Apparently most Republicans believe only in saluting. (One-third of Democrats agreed with this sentiment.) They will put aside critical analysis and blindly follow. Or maybe only when their own party is in charge. What is particularly disturbing about the answer to this poll question is that it does not measure the respondents' willingness to trust government leaders. After all, it's certainly possible that occasionally an administration, through hook and by crook, might be able to convince its citizens that a wrong action is a right one. (You think?) But the Pew Center question was exploring a different issue: would you support your government in prosecuting an unjust war? It did not put it in such blunt terms. The Pew Center used more colloquial terminology—just the sort of rhetoric usually deployed in political debates. Thus, the Pew Center determined that Republicans would spill blood for a mistake if spilling blood was equated with supporting the country.

I'd like to see what these Republicans would say if asked, "Would you be willing to give up your own life or that of a son or daughter for a war you believed was absolutely boneheaded?" But that's not how these questions get framed in real life.

It's hard to resist the cheap comparison of the GOPers' fight-for-my-country-right-or-wrong attitude to the we-we're-just-following-orders excuse used by you-know-who after World War II. But a large majority of Republicans, out of a distorted sense of loyalty to homeland, say they would should support a war that should not have been waged. They seem to believe it is a citizen's obligation to say "Yes, sir," and further the wrong. This is not patriotism. This is behaving like sheep.

Still fanatical under Obama

Sunday Feb. 22, 2009 07:36 EST

Fox News "war games" the coming civil war

Bill Clinton's election in 1992 gave rise to the American "militia movement": hordes of overwhelmingly white, middle-aged men from suburban and rural areas who convinced themselves they were defending the American way of life from the "liberals" and "leftists" running the country by dressing up in military costumes on weekends, wobbling around together with guns, and play-acting the role of patriot-warriors. Those theater groups — the cultural precursor to George Bush's prancing 2003 performance dressed in a fighter pilot outfit on Mission Accomplished Day — spawned the decade of the so-called "Angry White Male," the movement behind the 1994 takeover of the U.S. Congress by Newt Gingrich and his band of federal-government-cursing, pseudo-revolutionary, play-acting tough guys.

What was most remarkable about this allegedly "anti-government" movement was that — with some isolated and principled exceptions — it completely vanished upon the election of Republican George Bush, and it stayed invisible even as Bush presided over the most extreme and invasive expansion of federal government power in memory. Even as Bush seized and used all of the powers which that movement claimed in the 1990s to find so tyrannical and unconstitutional — limitless, unchecked surveillance activities, detention powers with no oversight, expanding federal police powers, secret prison camps, even massively exploding and debt-financed domestic spending — they meekly submitted to all of it, even enthusiastically cheered it all on.

They're the same people who embraced and justified full-scale, impenetrable federal government secrecy and comprehensive domestic spying databases conducted in the dark and against the law when perpetrated by a Republican President — but have spent the last week flamboyantly pretending to be scandalized and outraged by the snooping which Bill Moyers did 45 years ago (literally) as part of a Democratic administration. They're the people who relentlessly opposed and impugned Clinton's military deployments and then turned around and insisted that only those who are anti-American would question or oppose Bush's decision to start wars.

They're the same people who believed that Bill Clinton's use of the FISA court to obtain warrants to eavesdrop on Americans was a grave threat to liberty, but believed that George Bush's warrantless eavesdropping on Americans in violation of the law was a profound defense of freedom. In sum, they dressed up in warrior clothing to fight against Bill Clinton's supposed tyranny, and then underwent a major costume change on January 20, 2001, thereafter dressing up in cheerleader costumes to glorify George Bush's far more extreme acquisitions of federal power.

In doing so, they revealed themselves as motivated by no ideological principles or political values of any kind. It was a purely tribalistic movement motivated by fear of losing its cultural and demographic supremacy. In that sense — the only sense that mattered — George Bush was one of them, even though, with his actions, he did everything they long claimed to fear and despise. Nonetheless, his mere occupancy of the White House was sufficient to pacify them and convert them almost overnight from limited-government militants into foot soldiers supporting the endless expansion of federal government power.

But now, only four weeks into the presidency of Barack Obama, they are back — angrier and more chest-beating than ever. Actually, the mere threat of an Obama presidency was enough to revitalize them from their eight-year slumber, awaken them from their camouflaged, well-armed suburban caves. The disturbingly ugly atmosphere that marked virtually every Sarah Palin rally had its roots in this cultural resentment, which is why her fear-mongering cultural warnings about Obama's exotic, threatening otherness — he's a Muslim-loving, Terrorist-embracing, Rev.-Wright-following Marxist: who is the real Barack Obama? — resonated so stingingly with the rabid lynch mobs that cheered her on.

With Obama now actually in the Oval Office — and a financial crisis in full force that is generating the exact type of widespread, intense anxiety that typically inflames these cultural resentments — their mask is dropping, has dropped, and they've suddenly re-discovered their righteous "principles."

"Traditional" American values

Echoing Nixon and conservatives who fear the "new world order," the paramilitarists dread a "Jewish cabal." Hitler conceived his final solution because he hated minorities and these people seem the same. They're the same as, or closely allied to, the white supremacist and Christian fundamentalist groups. They all have similar aims: a return to "tradition," with WASP males on top and women, minorities, and gays somewhere below. (Perhaps six feet below...the ground.)

Americans killed Indians, Hitler killed Jews, and McVeigh killed government workers. Their goals were similar: to ensure that they and "their people" would dominate. The enemies change but the lust for power remains the same.

Actually, one could argue that all the so-called enemies are "liberals" or liberal stand-ins. Conservatives consider government workers to be meddlers, social architects, foes of private property. Jews, with their education, compassion for the poor, and philosophical search for truth, are generally liberal. And Indians—with their appreciation of nature, their communal ways, their lack of religious dogma or work-to-death ethic, must've seemed unnaturally "liberal" to early Americans, even if they didn't use that word. Modern commentators have criticized Indians for the same things—i.e., for being the last true "socialists."

The common thread is that conservative/libertarians can't stand anything but the status quo—what they consider normal or customary or "right." Which of course is why they're conservative/libertarians. Liberalism is tolerant and conservatism isn't, and conservative/libertarians can't tolerate that.

These people can't stand change or progress if it means recognizing, including, or promoting others. Heaven forbid we should have a world where everyone is truly free and equal. That's why they hate the idea of multiculturalism—because it means acknowledging that white male Christians aren't necessarily destined to rule.

No, conservative/libertarians would like to return us to a world where a "free market" ensures that robber barons rule, minorities stay "separate but equal," and Indian nations are terminated. In other words, where a government-free anarchy lets the strong trample the weak. Too bad it ain't gonna happen: not now, not ever.

The progressive majority won't let the regressive minority rule, but "libertarians" won't go the way of the dinosaurs quietly. We can expect more culture wars, both real and metaphorical. More militia strikes and anti-abortion terrorism. More white-boy shootings and violence. More racial, religious, and sexual discrimination. These are all symptoms of the Darwinist struggle for survival—the chaos "libertarians" would foist on us if they could.

Thus concludes this brief history of America's conservative/libertarians.

What to do about them?

Paul Waldman

July 12, 2006

Paul Waldman is a senior fellow at Media Matters for America and the author of the new book, Being Right is Not Enough: What Progressives Can Learn From Conservative Success, just released by John Wiley & Sons. The views expressed here are his own.

Ask a conservative what the biggest problem in America is today, and you'll get answers like overtaxation, a sexualized culture, lack of respect for authority, insufficient church-going or big government running amok. But if you then asked the conservative what the real source of the problem was—the beating heart pumping blood to each and all of these socio-politico-cultural wounds—you'd get the same answer: liberalism.

On the other hand, you could ask a liberal a hundred questions about the problems facing our country before you'd get to an answer that placed conservatism at the heart of the nation's ills.

And conservatives learn these messages when still young. What does a "campus liberal" do? Well, it depends what his or her issue is: fighting sweatshop labor, or environmental degradation, or the Iraq war, or any of a dozen other problems about which liberals are concerned. What, on the other hand, does a "campus conservative" do? Fight liberals and liberalism.

You can hear it in the media as well. As any fan of Limbaugh, Hannity or O'Reilly hears every day, whatever the issue is, the problem is liberals. Conservatives write books saying liberals are The Party of Death, who are Trashing Democracy, Waging War Against Christianity, Screwing Up America, Corrupting Our Future—and on top of it all, our whole ideology is A Mental Disorder. Liberals, on the other hand, write books about why George W. Bush is a terrible president. (I plead guilty.)

What we haven't yet seen from the left is a sustained critique, not just of a particular politician or a particular policy, but of the entire ideology and worldview of conservatism.

As everyone knows, conservatives have succeeded in making "liberal" an epithet, something they throw at their opponents—who try desperately to dodge the label. The demonization of "liberal" has been successful in part because conservatives have effectively created what social psychologists call a "schema" with decidedly negative features around the term. A schema is a set of ideas that are connected in people's minds, such that activating one idea—"liberal"—activates a whole set of related ideas, like lights on a Christmas tree. We assemble schemas as a way of storing and categorizing related information in memory. In this case, the related ideas are things like "soft on crime," "weak on defense," "sexually permissive," and so on. The ideas liberals would like to pop right up in people's heads when they hear the term liberal—"wants prosperity for everyone," "supports universal health care" or "stands up to powerful interests"—are farther away from the schema's center.

This didn't happen by accident. It is the result of a relentless campaign against liberalism by conservatives. And liberals need to do the same thing to conservatism.

A good first step would be to never, ever again use the word with a positive connotation. How many times has a Democrat, in order to score a debating point, said, "A true conservative wouldn't tolerate these Republican deficits?" How many times have solidly liberal Democrats described themselves as "fiscally conservative?" Those formulations accept that true conservatives are principled people with noble goals. They are not, and should not be talked about as though they were. When was the last time you heard a Republican call himself a "social liberal," even if he is one? They don't, because they understand that liberalism is an opposing ideology to which they will give no aid or comfort.

So allow me to offer a few points of attack on conservatism, ones that will resonate with the public and accrue both short-term and long-term gains to the liberals who use them.

1. Conservatism has failed. The overwhelming majority of the American public now sees the Bush administration as a failure. They failed in Iraq, they failed after Hurricane Katrina, they failed on health care, they failed to deliver rising wages, they failed on the deficit, they failed, they failed, they failed. Why? Liberals need to argue that it wasn't a product of incompetence, it was a failure of conservative governance. As Alan Wolfe put it in a recent Washington Monthly article, "Conservatives cannot govern well for the same reason that vegetarians cannot prepare a world-class boeuf bourguignon: If you believe that what you are called upon to do is wrong, you are not likely to do it very well."

Conservatives had their chance: a Republican president, a Republican Congress, Republican-appointed courts—in short, the perfect environment for enacting their vision with little to stand in their way—and they failed. Should we be surprised at the level of corruption? Of course not; they don't think government is there to serve the people, so why shouldn't they raid it for whatever they can grab?

In short, progressives should start talking about the Bush administration's failures not as those of a president, but of an ideology.

2. Conservatism is the ideology of the past—a past we don't want to return to. Liberals need to embrace the culture war, because we're winning. The story of American history is that of conservative ideas and prejudices falling away as our society grows more progressive and thus more true to our nation's founding ideals. Conservatives supported slavery, conservatives opposed women's suffrage, conservatives supported Jim Crow, conservatives opposed the 40-hour work week and the abolishment of child labor, and conservatives supported McCarthyism. In short, all the major advancements of freedom and justice in our history were pushed by liberals and opposed by conservatives, no matter the party they inhabited at the time.

Conservatism is Bill Bennett lecturing you about self-denial, then rushing off to feed his slot habit at the casino. It's James Dobson telling you that children need regular beatings to stay in line. It's a superannuated nun rapping you on the knuckles so you won't think about your dirty parts. It's Jerry Falwell watching "Teletubbies" frame by frame to see if Tinky Winky is trying to turn him gay. Conservatism is everyone you never wanted to grow up to be.

3. Conservatives are cowards, and they hope you are, too. We're afraid, they shout. We're so afraid of terrorists, we have to become more like the things we hate. We're so afraid, we have to let our government sanction torture. We're so afraid, we have to let the government spy on us. We're so afraid, we have to give the president dictatorial powers. We're so afraid, we just want to rush to the arms of politicians who say they'll protect us.

Progressives need to frame their rejection of the fear campaign as an act of courage: Al-Qaida does not scare us, and we will not dismantle our democratic system because we are afraid. The America we love does not cower in fear, as the conservatives want it to.

These are just a few ways progressives can begin to talk about contemporary issues in the context of the larger ideological conflict that shapes our political history. As an added bonus, when we make clear just what it is we are against at its fundamental, philosophical level, we define for the public who we are and what we stand for.

One of the troubling contradictions in contemporary public opinion is that while on nearly every issue the progressive position is more popular, the number of people willing to tell a pollster they consider themselves "conservative" still far outnumbers the number willing to say they're "liberal." It wasn't always that way, and it doesn't have to be that way. Winning converts isn't just about convincing people you're right on the merits of issues, it's also about showing them that your side is one they want to join, and the other side is one they want to avoid.

The key challenge facing progressives right now is how—once George W. Bush decamps for Crawford in January of 2009—to maintain the increased energy motivating the political left in recent years. They will be able to do so if they come to understand that George W. Bush is not what they need to fight. What they need to fight is conservatism.

Related links

Faith in free markets

The myth of American self-reliance

The myth of the liberal media

Right-wing extremists: the enemy within

A shining city on a hill: what Americans believe

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.