An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Star Trek Voyager: Chakotay:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Star Trek Voyager: Chakotay:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Star Trek Voyager: Chakotay:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Star Trek Voyager: Chakotay:

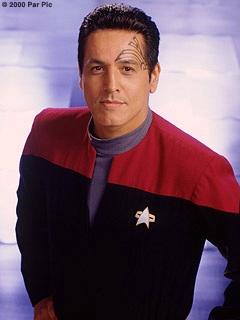

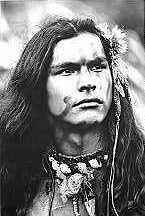

On UPN's Star Trek: Voyager, Robert Beltran played Chakotay, a Native American who attended Starfleet Academy before joining the rebel Maquis. The standard view is that Chakotay, the first continuing Native character in a Trek series, was an uplifting role model. "Chakotay is a passionate man who has earned Captain Janeway's respect as her friend and First Officer," Beltran once explained.

But Al Carroll (Mescalero Apache), a PhD student at Arizona State University, has another view. He dissected Chakotay's background in his thesis, "Depictions of Native Veterans in Fiction." Some excerpts:

The character of Chakotay in Star Trek: Voyager (STV) is every bit as much a creature of white fantasies as Billy Jack. STV's Chakotay is another "faithful companion" or sidekick to a white lead character, and in his own bizarre ways far more stereotypical than Tonto. At least Tonto was heroic and rescued the Lone Ranger once in awhile. Robert Beltran actually seems to imitate the old Westerns for his unflinchingly stone-faced Stoic portrayal. The character of Chakotay is a Frankenstein-like patchwork of New Age fantasies and misconceptions. STV's writers deliberately avoid making Chakotay a member of a tribe that exists anywhere outside a screenplay. This enables the writers to mix and match bits and pieces of New Age clichés about Natives without any regard for accuracy or believability. His fictional "Anurabi" tribe is from the South American jungles, yet venerates "sky people." Generally, the pantheons of jungle tribes involve forest creatures, not figures from the heavens they could hardly see through the jungle canopy. Chakotay's people also use the sweatlodge, which STV's writers falsely assume is a universal ceremony among all Native peoples. Apparently it never occurred to the writers that you don't need a lodge to sweat in the jungle.

Chakotay even invites his commanding officer, a white woman in her forties, to take part in a Vision Quest, a ceremony that is exclusively done for adolescent boys. Chakotay also urges Janeway to try and find her "animal totem" or spirit guide. Again, this is based on New Age misconceptions. Chakotay is not an elder or medicine man, he is an alienated member of his tribe (and thus would likely not even have much knowledge of traditions, nor would he be trusted with the intricate details of ceremonies) far from his fictive people. His "tribal tattoo" is more of an amusing mistake. Native facial tattoos tend to be far more elaborate, as well as symmetrical and covering both sides of the face. Yet television viewers would likely have recoiled in horror at an authentic looking tattoo, so STV's creators settled for a "cute" tattoo in one corner of his face that resembles an incomplete moko, not of any Natives in the Americas, but of New Zealand's Maoris. STV's writers even completely fabricate a non-existent ceremony, the "pakra," which resembles ancestor worship as practiced in Asia.

As many errors as the writers for STV made, it could actually have been far worse. In the original script for the episode "Tattoo," writer Larry Brody intended for Chakotay's people to be Mayans and gave them nonexistent "Mayan medicine wheels." Brody's script then began to resemble a Twilight Zone episode by further making the dubious assertion that the Mayan culture later became the Anasazi, leaping over several thousand miles and enormous cultural differences seemingly without any actual research.

All of these errors would be comical if not for the fact that STV's writers seem to be openly proselytizing their New Age beliefs, in sharp contrast to the usual militantly atheist viewpoint of Star Trek overall. Even the most cursory web search shows the reaction from fans to this New Age evangelism was overwhelmingly derisive and negative. Beltran himself was the target of much criticism for "passing." Beltran identified as Mexican until criticized by Natives, when he suddenly claimed to be Mayan. While his physical appearance leaves no doubt he has Indian ancestry, he has no ties to or understanding of Native cultures, as evidenced by his public defense of the New Age aspects of Chakotay as authentically Indian.

For the purposes of this study, the worst aspect of the Chakotay character is that it gives no insight into either Native peoples in general or Native veterans in particular, being content to spread New Age misconceptions instead. Even Chakotay's name is a clear signal to New Age followers. In the fictional Anurabi dialect, his name translates as Earth Walking Man or "Man Who Walks the Earth But Only Sees the Sky," every bit as pretentious as most other New Age "Indian names." In a further instance of New Age homogenizing of all Native cultures into one "generic Indian" framework, STV's writers openly modeled the Anurabi on a composite of Aztec, Mayan, Mixtec, and even Inca cultures. The writers further relied upon a number of New Age sites for information, and crosslink to them.

For all of their pretensions to having "enlightened" views of Natives, STV falls back on old stereotypes. Chakotay's people are shown as trapped or deliberately choosing to live in the past, even in the Twenty-Fourth Century. Indeed, Chakotay's choice to join Star Fleet is scripted as a complete rejection of his Native culture, rather than as adaptation. Naturally, STV's writers could not show successful Native adaptation to the military. Instead, they first make Chakotay into a mutineer and rebel leader. Naturally they also show Chakotay seeing the error of his ways thanks to his benevolent white leader, his commander Captain Janeway. STV's writers also seem to delight in undermining Chakotay by showing him as a bumbler. His commander is constantly rescuing him or reprimanding him for his "rebellious nature," and the principal white male character, Lieutenant Tom Paris, is often beyond Chakotay's ability to command. As with Windtalkers, the most positive thing to be said for this portrayal is that most of the public was smart enough to see through it and thoroughly reject it.

Alas. Even the future's fictional Indians are stereotypical.

More on Chakotay's background

From StarTrek.com:

Played by Robert Beltran

A Native American descendant, this onetime Starfleet lieutenant commander resigned from his position as an instructor in Starfleet's Advanced Tactical Training in 2370 to join the Maquis, sparked by his father's death fighting Cardassians on the tribe's homeworld along the Demilitarized Zone. Chakotay is a gentle man but resolute, and is one of the Maquis who are truly in the fight for principle, not mercenary gain or violent outlet — as was one of his students, Lt. Ro Laren.

Today Chakotay looks to his spiritual Mayan background for inner comfort — and doesn't mind sharing that belief with others when asked, or even enduring some good-natured ribbing about it from Torres and Paris, among others. He uses a spirit guide summoned by his medicine bundle, prays to speak with his father for guidance, and uses a Mayan-descended medicine wheel for self-healing. With a mother suffering from ongoing neck muscle spasms, he is also reportedly an excellent masseuse.

However, he didn't always have such reverence for his ancestors' ways. His father, Kolopak, was insistent upon finding their peoples' ancestral home and did so in the Central American jungle in 2344, when Chakotay was 15. But the young man had already been casting his lot with Starfleet crews patrolling the border, and stunned his father on that trip with the news he'd be leaving the tribe to attend Starfleet Academy, after his newfound aquaintance Captain Sulu agreed to sponsor him, even at his young age. Despite that resistance, Chakotay did learn many survival skills from his father, such as building log cabins and fire-starting.

Chakotay's piloting skills trace back to extensive and early Starfleet Academy training. From a freshman course over adjacent North America, he went to Venus to master atmospheric storms and had yet another semester dealing with asteroids in the Sol asteroid belt.

The virtual estrangement between father and son lasted until 2371, when Kolopak died defending his home in the early days of Cardassian harassment, even as the final border treaty was being signed. Chakotay took to wearing his tattoo, a symbol of those jungle descendants, to honor his father, who wore it also; even his own name is a cherished gift from his tribe. Later, Chakotay reported considering archeology as a second occupation, either in the field or in academics.

Chakotay's people, tracing their lineage back past Mayans to the Rubber Tree People of Central America, resisted the intrusion of more technological societies until the devleopment of warp drive in the 21st century allowed them to leave Earth and find their own home for good. One 20th century forebear he knows of was a schoolteacher in Arizona.

Even today, its members avoid modern devices such as transporters wherever they can, and he was taught that nothing is personally owned, save the courage and loyalty in one's own heart. Despite his tribe's move, the adult Chakotay means Earth when he thinks of "home" — from the Arizona desert and the Baja California peninsula over to the Gulf of Mexico.

Needless to say, such things as medicine bundles and wheels aren't part of the traditional Maya culture. Instead, they're part of the New Age stereotype. Namely, that all Indian cultures embrace such things as vision quests, sweat lodges, animal totems, and spirit guides.

More on Chakotay the good Indian

U.S. Studies Online: The BAAS Postgraduate Journal

'Neutralising the Indian': Native American Stereotypes in Star Trek: Voyager

Lincoln Geraghty

© Lincoln Geraghty. All Rights Reserved

Star Trek's effort to produce an environment of equality and pluralism in space fails because it uses the assimilationist model for the Federation—described as 'a homo sapiens only club' by the Klingon Ambassador's daughter in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country [1991]. Any ‘alien' that comes in contact with the organisation, or even the minority members of the cast, is made subordinate to a self-evident superiority. Newfield and Gordon (1996: 81) call this sort of assimilationism ‘assimilationist pluralism' because it insists on conformity to the core even if it professes its belief in plurality. Henceforth Star Trek's ‘IDIC' ideology assumes then that everyone is equal in their diverse attributes but only if they are willing to accept the white dominated cultural control that the Federation symbolises. Star Trek's multiculturalism is a fallacy and yet because it is assumed that Star Trek mediates a positive multicultural message, the thin layer of racial stereotyping and inequality is hidden.

.

.

.

When Voyager undertook the placement of a Native American character on board the ship, its representation of Indians became entirely assimilationist and marginalist. Chakotay's character, if treated properly, should have forced an examination of colonial relations with the US, and in Star Trek's case, the Federation. However, my research has found that this is not the case and as a result Voyager manages to isolate the Native American in the show and American society. Consequently it assimilates him into a white dominated society without recognising the cultural diversity such a character should bring to the series. The Indian is continually stereotyped as isolated and separate from American society, just as he has been throughout history. Incorporating Chakotay into Voyager – as a sort of ‘Indian for Indian sake' character – before recognising the dominant colonizing role white society has played, and still plays, with Native Americans ultimately incorporates him into the same assimilationist pluralism that Star Trek has been practising for more than thirty years.

.

.

.

Chakotay's heritage is explained in the episode 'Tattoo' [1995]; he is a member of the Rubber Tree People of Central America yet there is no specific name for his tribe. Instead he follows the archetypal patterns of Indian tribal society. Euro-Americans have continually viewed the Indian people as one entity, not as separate groups of people who differ as much from each other as they do from white people. Star Trek's failure to cast Chakotay as anything but the generic Indian within a tribe that seeks knowledge from its honoured ancestors falls into the historic trap of simplifying the Indian. Robert Berkhofer Jr. recognises in his 1978 book The White Man's Indian, that all Indians have been seen as one and the same. Since Columbus, they have not been seen as a diverse and multicultural people:

Not only does the general term Indian continue from Columbus to the present day, but so also does the tendency to speak of one tribe as exemplary of all Indians and conversely to comprehend a specific tribe according to the characteristics ascribed to all Indians (Berkhofer Jr., 1978: 26).

Chakotay is again left in the shadows, visible only when he acts as the stereotypical Indian. In most episodes the rituals and ceremonies of Chakotay's heritage are highlighted and celebrated by his crewmates, but are all too often dismissed as examples of the ancient ‘Other'. His generalised Indian characteristics are things that are part of an Indian heritage not allowed a place in the twentieth century, let alone the twenty-fourth.

When Chakotay came aboard Voyager and was made first officer, Star Trek was paralleling famous Colonial American incidents of the Native Savage coming to the aid of white explorers. Mythical Indian figures from America's past have historically been portrayed as ‘friendly' Indians, willing to help the ‘superior' whites until they had mastered the frontier. Pocahontas helped John Smith survive execution at the hands of the Powhatan Chief; Sacajawea interpreted for Lewis and Clark on their epic expedition of the unknown American frontier; and, most monumental of all, Squanto helped the Puritans survive winter and celebrate the first Thanksgiving. The similarities between the role of Chakotay on board Voyager and Squanto are striking, yet they serve to illustrate that although they both hold important places within a group they are both isolated because they are Indian.

Squanto was an important figure in his band, a pniese to his sachem, which meant he was able to call upon the powerful tribal spirits to help his fellow warriors fight their enemies. This type of ‘vision quest' was important to his band and showed that he was a respected member. Chakotay is also able to embark upon ‘vision quests' in order to help Voyager. In 'The Cloud' [1995] he directs Captain Janeway on her own ‘vision quest' to help the ship out of danger. Like Squanto helped his sachem, Chakotay helps his captain, their powers being all-important to the survival of their communities. Neal Salisbury (1981: 231) describes the pniese's role as an aid to the tribal leader: 'They constituted an elite group within the band, serving as counselors and bodyguards to the sachems'. Throughout Voyager's run Chakotay has always acted as a counsellor to Janeway, sometimes running into a conflict of ideas, yet remaining ever loyal.

In some episodes it has been hinted that there might be more between Chakotay and Janeway, yet it has never been fully explored. In 'Resolutions' [1996] the two of them are forced to remain on a planet together and Janeway asks Chakotay to define some 'parameters' for their relationship. His reply is in the form of 'an ancient legend among [his] people', describing the joining of two tribes, one led by a woman the other by a warrior male. The story becomes a metaphor for what Chakotay feels about Janeway: Nothing but an undying desire to stand by her and to lighten the burden of captaincy. Chakotay puts himself in the service of his captain. Yet by this statement and Janeway's inquiry, he is not allowed anything more personal, indicating that the white woman is out of reach of her Indian admirer.

The parallels with Squanto do not end there, Salisbury (1981: 229) described him as having 'participated in the intensely ritualized world of trade, diplomacy, religious ceremonies, recreation, warfare, and political decision making that constituted a man's public life'. Chakotay is a deeply ceremonial man who wants to honour his father. Plus he is constantly involved with the political and social ramifications of the merging of the Maquis and Starfleet crews, he is always playing the political advocate. In 'Alliances' [1995] he tries to keep relations calm as the ship heads home under the command of the Starfleet captain, even though many Maquis crewmembers think that they should forget Starfleet rules and protocols. Interestingly, he suggests making an alliance with the Kazon-Nistrim – the savage Indians – in order to get the ship home safely.

Squanto and Chakotay are both 'white man's Indians' and are therefore allowed to fit into their adopted societies more easily. Squanto was accepted into the English colony because he helped them in times of hardship and adapted to become their version of a noble savage. Chakotay fits into Voyager's crew so well because he is respected and has proven his worthiness to them when they are faced with unique circumstances that only he can handle. Yet both men are left isolated from their friends. Squanto is the only Patuxet left after his band was wiped out by disease, on his deathbed he hoped that he be accepted by the 'Englishman's God in Heaven' because he had been alone among whites for some time before his death (Salisbury, 1981: 244). Chakotay is many thousands of light years from 'the sacred places of [his] grandfathers, far from the bones of [his] people', so he must live in isolation within a community that has accepted him, yet continue to treat him as the ‘Other' because of his spiritual and Native beliefs.

.

.

.

Gene Roddenberry's vision of a future where everyone is included does not appear to be a viable one on Voyager. Like so many other media of popular culture, Star Trek has failed to recognise that Native Americans are still a living and breathing presence in America. To exploit a phrase used by William Cronon (1983: 164) when writing about the changing Native American relationship with the New England landscape: 'By ceasing to live as their ancestors had done, they did not cease to be Indians'. Because of Star Trek's inability to understand modern Native American identities, and recognise that Indians have not 'vanished' and will probably not have 'vanished' by the twenty-fourth century, the character of Chakotay and the image of the Indian have suffered. Rather than the 'white man's Indian' stereotype Star Trek, and science fiction in general, should be looking at what the 'red man's Indian' is and where he fits in both society of today and the future. It is important to remember that the under-represented themselves have conflicting ideas about how they should appear to the majority culture now that they are increasingly becoming more active in the political arena, at the same time that the assimilationist culture may sincerely wish to move beyond its own stereotypes and realise there is nothing so historically concrete to replace them with. To quote Bordewich (1996: 343-344): 'To see Indians as they are is to see not only a far richer tapestry of life than our fantasies ever allowed but also the limitations of futile attempts to remake one another by force'.

More on Chakotay

Chakotay's tribe in Voyager

Chakotay the "other" in Voyager

Related links

New Age mystics, healers, and ceremonies

Tonto and the "good Indian"

Native veterans in fiction

The Indian-Star Trek connection

TV shows featuring Indians

Readers respond

"[T]he idea that US history and indian rights should be a focus on Voyager is as silly as having any black character dealing with slavery—in the 24th century."

"I can tell you that your article quoting [Robert Beltran] is completely wrong."

"Why aren't white characters ever referred to as stereotypical?"

"Some tribes allowed women to have vision quests. It depended on the tribe."

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.