California Imaging: Framing the Indian

By Rob Schmidt

The view that tribes are wealthy and powerful is a pervasive one. It's held to varying degrees by the public, the media, and politicians. A recent Google search generated 10,100 hits for "rich tribes" but only 635 for "poor tribes."

The twin poles of controversy are California and Connecticut, the two biggest Indian gaming states. In Connecticut, critics such as Jeff Benedict claim the dark-skinned remnants of centuries-old tribes aren't real Indians. But California is where the most conflicts seem to bloom.

In many ways, California's tribes are leading the resurgence among Native people. This is where they won the Cabazon decision in 1987 and passed Propositions 5 and 1A in 1998 and 2000. Here they operate the most successful collection of casinos in the country, earning more than $6 billion a year. Their leaders are some of the staunchest advocates of tribal sovereignty and self-determination.

Therefore, it's instructive to look at the case of California. The Golden State is where the American Indian's image is being framed—in more ways than one.

While Indians were mired in abject poverty in the 1950s through 1970s, few if any newspaper articles appeared about them, says Michael Lombardi, a tribal gaming consultant. "The attitude was one of complete and total ignorance." Even as recently as 10 years ago, he adds, most journalists were still uninformed. "What they knew about Indians is what they saw in John Wayne movies."

Newspapers did write about Indians, but their work was inadequate. They oversimplified complex stories, telling of Indians who were living in misery but not why. They focused on conflicts and scandals—the tribal equivalent of a car chase or celebrity trial. With their short-term mentality, they covered breaking events well, but failed to provide the larger historical context.

If you go through the archives, says Frances Snyder a PR consultant and member of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, you notice "a certain kind of tone in the way that our tribe was covered. And it was probably reflected throughout California and the US." Tribes were considered victims who didn't have much money and needed help.

In short, the media determined how people viewed Indians. The picture was a modern-day version of an Edward S. Curtis photograph: Indians huddled in blankets, stoically enduring hardship, resigned to their fate.

Once the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act passed in 1988 and tribes began negotiating compacts with California, things were bound to change. Suddenly Indians were playing a high-stakes game for potentially billions of dollars. But the media still didn't tune in to this new reality.

One of the few stories on the negotiations claimed tribes soon would be operating more than 200,000 slot machines (100 tribes x 2,000 slot machines each). "That was the kind of reporting that was going on," says Lombardi. "That was not reporting, that was hysteria."

When Governor Pete Wilson signed restrictive compacts with 11 tribes and stonewalled the rest, the Indians took their case to the public. They executed a well-planned media campaign to pass a ballot initiative, Proposition 5, to ratify their deals. The centerpiece was a series of TV commercials featuring the unassuming and telegenic Mark Macarro, chairman of the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians. Macarro avoided the daunting word "sovereignty" and instead spoke of self-governance and self-reliance.

Because they were spending a lot of money, the tribes finally got journalists assigned to them. Newspapers ran front-page pieces on the campaign. "And the main storyline of Proposition 5 was 'Tribes Spend $66 Million to Defeat Las Vegas,'" says Lombardi. "That was the sound bite. That was the headline in virtually every story."

But the tribal message of self-reliance resonated strongly with a public inculcated in the values of individualism. Despite the opposition of business and labor groups, Prop. 5 won by a wide margin. After a technicality invalidated it, the tribes went to the voters again, passing Prop. 1A in 2000. Both initiatives garnered more than 60% of the vote.

A lull followed as California's tribes made plans to expand old facilities or build new ones. In 2002, these efforts began to enter the public consciousness. Columnists complained about the tribal "monopoly" on gaming. Conan O'Brien joked that NASA sent a Native astronaut to convert the Mir space station to a casino. The innocuous "Family Circus" cartoon showed a boy playing Indian casino owner.

Gaming became the primary focus of articles about Indians. As the Native American Journalists Association reported,

The majority of Native American coverage fell into three topic areas: casino gaming by tribes, mascot team names and "on the res" datelined stories. ... The Los Angeles Times and The New York Times covered the [gaming] topic extensively because of controversial approvals of new tribal casinos in their states. ... But most casino stories were focused on government process. They contained comments from government bureaucrats who expressed suspicions of tribal enterprises. They turned potential stories about economic successes into redundant and sometimes negative accounts.1

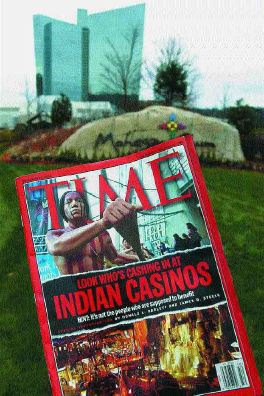

Time "exposes" Indian gaming

If that was the situation in mid-2002, it was about to get worse. That year the Wall Street Journal editorialized several times against Indian gaming.2 In December, Time magazine published a multipart "expose" of the industry.3 Among its claims:

Defenders of Indian gaming quickly condemned Time's study, but the damage was done. Editorialists around the country weighed in with their own tsk-tsks and tut-tuts. Few of them did any original reporting; they simply assumed Time's reporting was true and repeated it as such.

California's supposedly liberal media chimed in. In the Los Angeles Times, columnist Steve Lopez wrote that "compacts are essentially a reparations program" and called a lawyer representing Indians "Chief Running Mouth."4 Bill Lynch, editor of the Sonoma News, penned a whole series of editorials denouncing Indians.5 They will "say and do anything to get what they want," he wrote. Gaming tribes are "shills" for their "corporate godfathers." California should oppose gaming by "allegedly abused" tribes.

Snyder points to several examples of media bias against her tribe. When patrons of the new Chumash casino told a TV reporter they liked it, he kept asking questions such as, "No, how do you really like it?" When a fire alarm caused a routine evacuation, a TV editor kept asking if the situation was "chaotic" and ran five stories on it. A print reporter spent two years researching the tribe, but his articles led with the members' felony conviction and divorce rates, though they weren't necessarily higher than the surrounding community's.

One Associated Press reporter told Snyder his editors insisted on inserting the adjective "casino-rich" whenever he wrote about tribes. Somehow, the positive message of tribal self-reliance was morphing into a negative message of tribal greed and corruption.

Fanning the flames were self-appointed activists who opposed Indian gaming on the dubious grounds that it was antisocial or unconstitutional. In California the most prominent one has been Cheryl Schmit and her Stand Up for California group. Similar organizations have sprung up around the country: One Nation in Oklahoma, Upstate Citizens for Equality in New York, Citizens Equal Rights Alliance in Washington.

These activists have trouble proving the breadth and depth of their support, but the media gives them a boost. By quoting them as often as gaming proponents, journalists say they're providing balance. In fact, they're making it seem as if two evenly matched sides are engaged in a closely fought battle. The audience can't tell if the opposition to gaming is a widespread grassroots movement or three cranks with a cellphone and a website.

"The media loves people like Cheryl Schmit," says Lombardi. "A white lady fighting against the Indians is right out of the movies."

According to the polls, notes Lombardi, most Californians continue to support Indian gaming. When people list which issues concern them, he says, "I see immigration, education, environment, crime, the budget, the economy. I never see Indian gaming.

"Nobody cares [about gaming foes] except the reporters that like to quote them because they like conflict," he adds. "The vast majority of Americans love Indian casinos. I know. I see them in the casinos every time I visit. They're voting with their feet."

Then why so much scare talk about casinos? After all, they've operated successfully in Las Vegas for decades. Some of it is genuine concern about negative effects such as traffic, crime, and addiction. Fear of the unknown is a powerful force, especially if it's phrased in terms of "The Indians are coming!" Who wouldn't be afraid of a "foreign" nation that allegedly can ignore laws?

Communities often oppose Indian casinos before they open. They often realize their fears were overblown after the casinos open. A study done in Massachusetts shows how benign the impact may be:

The introduction of Vegas-style casinos to the Bay State would bring modest gains in jobs and home prices, lead to slightly higher bankruptcy rates and reported crimes, but would have "surprisingly little impact" on the economy and crime in Massachusetts overall, according to a study being released today.6

In 2003 Arnold Schwarzenegger proved the debate wasn't just about the aftereffects. As the Time magazine controversy was dying down, he stoked it by stigmatizing Indians during the recall campaign. Tribes were a "special interest," he claimed.7 They weren't paying their "fair share."8

Schwarzenegger also accused California's tribes of spending $120 million to buy Sacramento.9 Never mind that the reality was different. Yes, the tribes spent $92 million to pass two propositions, but that went directly to educating voters, not influencing politicians. A hundred-plus tribes gave the rest of the money to dozens of federal, state, and local politicians over several years—meaning the average donation was relatively small.

"That's scapegoating," says Lombardi. "That's what Adolf Hitler did to the Jews in Germany. 'They're the reason we lost World War I. They own all the banks. They control everything.'"

Schwarzenegger had been in a tight race with Lt. Governor Cruz Bustamante, a Democrat, and State Sen. Tom McClintock, a Republican, trailing. After Schwarzenegger's attacks, 6-8% of the electorate shifted from McClintock to him. That was enough to give him a comfortable victory.

Ironically, some tribes hurt Bustamante by making large donations to him. Even though other tribes criticized these bequests, they validated the "special interest" charge in the public eye. "Only four tribes gave him money," says Lombardi, "but all the tribes took the blame for it, and it gave the governor the opening to play the race card and win the election."

Critics deny racism

Although Schwarzenegger slammed "tribes" as a whole, not "the few tribes wealthy enough to influence politicians and political campaigns," he denied any racist intent. That's also the position activists such as Schmit take. Nevertheless, some see darker motivations behind the opposition to Indian casinos.

"We're now experiencing economic racism," one tribal leader told Snyder. As Snyder explains it, "They don't like you today because in their minds, people of color are not supposed to be financially successful. We've upset the apple cart ... because we're supposed to be their gardeners and their housekeepers and their maids."

When voters approved Propositions 5 and 1A, she surmises, they still thought of Indians as victims. "Oh, let's let these little Indians have their little casinos," she imagines them saying. "It'll be cute, and they can earn some money and they can go off welfare. Well, they never thought in their wild dreams—nor, I think, did we—that gaming would be so incredibly popular."

As evidence, she recounts a conversation with a Manshantucket Pequot from Connecticut. The man noted that the Pequots have darker skins than the neighboring Mohegans. "The difference in how they were treated in the community was obvious and significant," she relates. People felt more at ease with the lighter-skinned Indians.

Why would the media allow and encourage this semi-racist mentality? Despite a philosophy of speaking truth to power, today's newspapers and magazines are part of media conglomerates. They push the interests of their primary readers, the white middle class. They share the mindset of America's capitalist culture, which says the social status quo is good and anything threatening it is bad.

Progress has always been the national credo. Like Ronald Reagan before him, Schwarzenegger embodied a can-do attitude of action and achievement, which almost ensured his triumph. California's Indians were doing the same thing—pulling themselves up by their bootstraps— but only the ex-Terminator got applause for it.

The recall election was a watershed for the tribes—a metaphor-changing moment. They had pictured themselves as the rightful claimants of a Jeffersonian tradition of limited government and taxation. With the media's aid, they were framed as opportunists and rule-breakers. Like Ebenezer Scrooge or Tony Soprano, they were stuck being seen as grandees of greed who would do anything for a buck.

Since that election, other matters have thrust California's tribes into the spotlight—often to their chagrin. One is the difficult issue of disenrollment. Several gaming tribes have removed hundreds of members from their rolls, making them ineligible for casino payments. The most publicized example occurred in March 2004, when the Pechanga tribe expunged 130 members.

Critics in the media say disenrollment is a classic grab for wealth and power. As a tribe shrinks, each remaining member gets more money, they observe. But "they manage to leave out certain facts that would change the tone of the article," says Snyder.

If a disenrollment-for-profit story were true, she admits, it would be newsworthy. But "in many cases, it's not true. Those fights go back for decades, long before casinos were even an issue." Many involve old family disputes and rivalries that money has only exacerbated.

Another thorny issue is reservation shopping: the notion of opening casinos in urban locations far from traditional reservations. The epitome of this was the San Pablo case. In 2000 Rep. George Miller (D-Calif.) slipped a sentence for the Lytton Band of Pomo Indians into congressional legislation. This bypassed the land-into-trust process and turned 10 acres in San Pablo, near Oakland, into tribal land.

In 2004 the Lyttons signed a compact to open a Nevada-style casino with 5,000 slot machines on that land. Protests quickly convinced the Legislature to block the San Pablo deal, and the tribe renounced the idea of a mega-casino. To the media, this was an instance of narrowly defeating the greedy Indians who sought a casino on every corner. People overlooked two key points: It was only one tribe and the regulatory process worked.

Pundits have speculated about a casino in places like Garden Grove, near Disneyland. Such talk is "yellow journalism," says Lombardi. "Under federal law it won't happen. There are plenty of safeguards."

In the November 2004 election, card clubs and racetracks vied with tribes to expand gaming via Propositions 68 and 70. Gov. Schwarzenegger went ballistic. "It is tremendous greed," he told an LA Times reporter. "They want to rip off the people…pull the wool over people's eyes."10 Schwarzenegger didn't limit himself to "gaming tribes advocating Proposition 70" or "gaming tribes," period. Twice more he attacked "the Indians," as if they were all guilty of rapacious behavior, before he was forced to back down.

"Here's a guy from Austria who comes to America saying, 'Those Indians are stealing from us,'" said Richard Milanovich, chairman of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, to The Desert Sun. "It's no different than saying, 'Those darn Mexicans are stealing from us.' If that isn't a racist attitude, I don't know what is." (Both propositions lost, which proved the public favored the status quo.)

The Jack Abramoff scandal is the latest problem to rock the Indian gaming landscape. Hired by a handful of tribes to lobby for them, Abramoff proceeded to bribe members of Congress. In January 2006 he pleaded guilty to three counts of conspiracy, fraud, and tax evasion.

Commentators have had a field day. "This strange turnabout was predictable to anyone who has followed the connection around the country between wads of gambling money and sleazy practices in government," scolded Rich Lowry, editor of the National Review. "With every new tribe and casino, there is more loot to be poured into politics."11

In an op/ed piece, Melanie Benjamin, chief executive of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe Indians, rebutted such charges:

Certain editorial boards have portrayed this mess as an "Indian" scandal rather than what it is: a lobbying scandal. Legislative proposals are circulating that would restrict or ban all tribal political giving. One commentator in the Wall Street Journal even called for reservations to be done away with.

A few anxious politicians have hopped aboard that wagon train in a transparent attempt to disguise their own misdeeds and portray themselves as the victims of Indian money, although there is no evidence that even one tribe did anything wrong. In a tradition as old as America itself, some in Congress now vow to punish and "reform" the Indians.12

If gambling money leads to influence peddling, no one wants to dismantle Las Vegas or Atlantic City. These days Indian casinos are "the big 500-pound gorilla that people love to hate," says Snyder. "We're almost the equivalent of Wal-Mart. That's the tone that people have started taking with us."

What do Indians want?

Rather than conflict and controversy, what would California's tribes like to see in the media? Among other things, a recognition that they're not monolithic—that not all of them are rich or have casinos. That gaming has been a huge success for Indians, alleviating poverty and allowing a cultural renaissance. That Indian gaming is well-regulated, with three layers of oversight, and that tribes are contributing funds to their local communities.

Two items top the tribes' wish list. One is an acknowledgment that they're sovereign entities, not ethnic associations or social clubs. "That they actually are governments," says Lombardi. "That they've been governments [since] before there was a United States of America."

That, more than anything, summarizes what the struggle to legalize Indian gaming was about, he continues. "It wasn't about slot machines in the end. What it was really about was, do the tribes have a right to pass their own laws on their own land?"

The other request is that journalists put their stories into context. Reporters should take the time to learn about a tribe's history and culture, its casino business, and the complexities of Indian gaming. Then they'd understand that Congress didn't "grant" sovereignty to tribes or intend gaming to be a welfare program, as critics would have it.

Snyder touts one reporter who did a good job. "We didn't like her because she ... said great things about the tribe," says Snyder. "We liked her because she was very objective. She didn't care which way the story went. She just wanted to get the facts.

"As a result she was fair. There were things that maybe we didn't like ... but she provided both sides to the story." That's all Indians want: coverage that's truly fair and balanced.

Notes

1. The Reading Red Report, Native American Journalists Association, 2002. Posted at http://www.naja.com/resources/publications/2002_reading-red.pdf.

2. Links posted at http://www.bluecorncomics.com/wsj.htm.

3. Links posted at http://www.bluecorncomics.com/timeresp.htm.

4. Links posted at http://www.bluecorncomics.com/gaming.htm#critics.

5. Ibid.

6. "Study finds casinos would have modest impact on state's economy." Lowell Sun, January 13, 2005.

7. Links posted at http://www.bluecorncomics.com/gaming.htm#critics.

8. Ibid.

9. "Have gaming tribes bought California for $120 million? No." Indian Country Today, October 7, 2003.

10. Links posted at http://www.bluecorncomics.com/gaming.htm#critics.

11. "The Tribal/casino scandal." Neshoba Democrat, January 18, 2006.

12. "It's a lobbying scandal, America, not an 'Indian' one." Minneapolis Star Tribune, March 14, 2006.

This article is available for reprint but may not be reprinted without permission. Contact the author for details. All rights reserved.

More information about Native stereotyping

Tipis, feather bonnets, and other Native American stereotypes

A brief history of Native stereotyping

Stereotype of the Month contest

Related links

The critics of Indian gaming—and why they're wrong

Native journalism: to tell the truth

Author's Forum

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.