An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay The Indian-Oz Connection:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay The Indian-Oz Connection: An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay The Indian-Oz Connection:

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay The Indian-Oz Connection:

The book Was is a fictional account of the "real" Dorothy. According to author Geoff Ryman, she was a girl named Dorothy Gael who lived in Kansas with her aunt and uncle and met a substitute teacher named Frank Baum. It's must-reading if you're an Oz fan.

In the story, Ryman imagines how Baum transmuted the local Indians into the various races of Oz. Here's an impressionistic passage explaining the connection as Ryman sees it:

"Are there any Indians?" Dorothy asked.

Not anymore, Etta told her. But near Manhattan, there had been an Indian city.

"It was called Blue Earth," said Etta. "They had over a hundred houses. Each house was sixty feet long. They grew pumpkins and squash and potatoes and fished in the river, and once a year they left to hunt buffalo. They were the Kansa Indians, which is why one river is called the Kansas, and the other is called the Big Blue. Because they met right here where the Kansas lived."

Dorothy saw it, a river as blue as the sea in her picture books at home. The Kansas River was called yellow, and Dorothy saw the two currents, yellow and blue mixing like colors in her paint box.

"Is it green there?" she asked. She meant where the blue and yellow mixed.

"It's green everywhere here," Etta answered.

So Munchkin blue and Winkie yellow merged to create the Emerald City. And the Kansa Indians, who were either relocated or dead by Dorothy Gael's time, were the mythical "others" who inspired her fantasies. If you believe "Was," L. Frank Baum used Dorothy's Indian reveries to create his Oz books.

Although the connection (probably) isn't true, we can't be sure about Baum's inspirations. He may have modeled Oz unconsciously on the things he saw and knew. That Indians inspired him is a nice thought, anyway.

What is true is that the Indian represents something fundamental to most Americans. I've argued before (see America's Cultural Roots) that Euro-Americans absorbed many of their values—the love of freedom, individualism, and justice—from the Natives they pushed aside. Some claim America is a Christian nation, but Christianity has always been authoritarian, orthodox, and oppressive. More than anything, the land of the free and home of the brave is a "pagan" Indian country.

Baum: beloved or bigoted?

Readers of PEACE PARTY #1 know there's more to the Oz story. If Baum was inspired by Indians, he certainly didn't like them. As editor for the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, he wrote two virulently anti-Indian editorials before and after Wounded Knee. In one he said:

The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians.

As with Mark Twain (ICI #59), Baum's bigoted writings belie his popular image as beloved storyteller. Native people have opposed attempts to honor Baum for just this reason. For more on the story, see below.

The full story on Baum

This essay was published in PEACE PARTY #1.

Twisted Footnote to Wounded Knee

By Robert W. Venables

Spring 1990

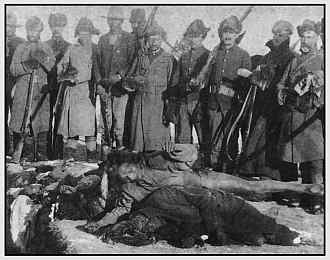

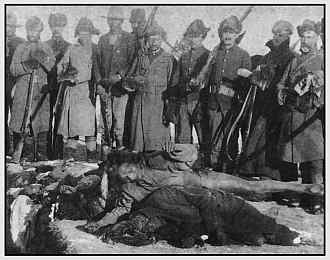

One hundred years ago, on December 29, 1890, in a ravine near Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, the U.S. Army, supported by American Indian mercenaries, slaughtered approximately 300 Lakota men, women and children—75 percent of Big Foot's Lakota community. Two-thirds of the massacred Lakotas were women and children. Only 31 of the 470 soldiers were killed, many by "friendly fire" of fellow soldiers.

Big Foot's Lakota followers had already surrendered when they were brought to Wounded Knee by the army. While the Lakota warriors were being disarmed, fighting broke out. Any real resistance on the part of the warriors was quickly over. But atrocities escalated as the U.S. troops turned their weapons—including four rapid-fire Hotchkiss guns—against clearly defeated warriors and innocent women, children and old men. Women and children trying to escape were pursued and slaughtered. An official U.S. report noted that "the bodies of the women and children were scattered along a distance of two miles from the scene of the encounter."

"Extermination" Proposed

The following quotes were printed in the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, a weekly newspaper published in Aberdeen, South Dakota. The first was published immediately after Sitting Bull's assassination by Indian Police Dec. 15, 1890.

"Sitting Bull, most renowned Sioux of modern history, is dead.

"He was an Indian with a white man's spirit of hatred and revenge for those who had wronged him and his. In his day he saw his son and his tribe gradually driven from their possessions: forced to give up their old hunting grounds and espouse the hard working and uncongenial avocations of the whites. And these, his conquerors, were marked in their dealings with his people by selfishness, falsehood and treachery. What wonder that his wild nature, untamed by years of subjection, should still revolt? What wonder that a fiery rage still burned within his breast and that he should seek every opportunity of obtaining vengeance upon his natural enemies.

"The proud spirit of the original owners of these vast prairies inherited through centuries of fierce and bloody wars for their possession, lingered last in the bosom of Sitting Bull. With his fall the nobility of the Redskin is extinguished, and what few are left are a pack of whining curs who lick the hand that smites them. The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians. Why not annihilation? Their glory has fled, their spirit broken, their manhood effaced; better that they die than live the miserable wretches that they are. History would forget these latter despicable beings, and speak, in later ages of the glory of these grand Kings of forest and plain that Cooper loved to heroism.

"We cannot honestly regret their extermination, but we at least do justice to the manly characteristics possessed, according to their lights and education, by the early Redskins of America."

Writer Is Well Known

In short, the editorial begins ambivalently but concludes by calling for the extermination of American Indians.

The editor and publisher of the Aberdeen Pioneer who advocated genocide is well known. His name is L. Frank Baum. A decade later, his book The Wizard of Oz (1900) would become a classic.

After wishing everyone a Merry Christmas on December 20, the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer published another editorial on January 3, 1891, after the Wounded Knee massacre:

"The peculiar policy of the government in employing so weak and vacillating a person as General Miles to look after the uneasy Indians, has resulted in a terrible loss of blood to our soldiers, and a battle which, at best, is a disgrace to the war department. There has been plenty of time for prompt and decisive measures, the employment of which would have prevented this disaster.

"The PIONEER has before declared that our only safety depends upon the total extirmination [sic] of the Indians. Having wronged them for centuries we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth. In this lies safety for our settlers and the soldiers who are under incompetent commands. Otherwise, we may expect future years to be as full of trouble with the redskins as those have been in the past.

"An eastern contemporary, with a grain of wisdom in its wit, says that ‘when the whites win a fight, it is a victory, and when the Indians win it, it is a massacre.'"

Editorials Were No Joke

I first obtained a microfilm copy of Baum's Saturday Pioneer in 1976, believing that I would probably find editorials which protested the massacre of Wounded Knee. After all, what else would one expect from the original Wizard? After mulling over the editorials for fourteen years, I must admit to the reader that I still love both the books and the movie.

But what of L. Frank Baum? I've tried to read his editorials as satire or parody—even as proto-Monty Python. They aren't.

The editorials at points are curiously ambivalent—the description of Sitting Bull, for example. But their core message is genocide. Like so many humans who are capable of uttering and doing the unthinkable, L. Frank Baum was in many respects a sensitive and loving man. But I don't believe it is enough to say that his editorials are an indication of how, in Baum's era, calls for genocide were not aberrations, that they were widely held, and that they were public.

I have instead been haunted by a hypothetical parallel: Imagine what the reaction would be if a former Nazi newspaper editor who had advocated the "Final Solution" had, ten years after World War II, published a children's book in Germany. Imagine that this author and this children's book became world famous. Imagine a movie, with wonderful music.

All this is possible—if Germany had won the war.

By Robert W. Venables, Senior Lecturer, American Indian Program, Cornell University.

First published in the Northeast Indian Quarterly (Spring 1990) of Cornell University's American Indian Program. Adapted and reprinted by permission.

Indian-hating in Oz too?

Thursday June 08, 2006

Thomas St. John: Indian-Hating in 'The Wizard of Oz'

In the weeks before and after the massacre at Wounded Knee, Frank Baum printed his editorials calling for the total extermination of all Indians.

"The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians. Why not annihilation? Their glory has fled, their spirit broken, their manhood effaced; better that they die than live the miserable wretches that they are. History would forget these latter despicable beings, and speak, in later ages of the glory of these grand Kings of forest and plain that Cooper loved to heroism." — Lyman Frank Baum, Saturday Pioneer, December 20, 1890.

By Thomas St. John

PalestineChronicle.com

Lyman Frank Baum (1856-1919) advocated the extermination of the American Indian in his 1899 fantasy, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Baum was an Irish nationalist newspaper editor, a former resident of Aberdeen in the old Dakota Indian territory. His sympathies with the village pioneers caused him to invent the Oz fantasy to justify extermination. All of Baum's "innocent" symbols clearly represent easily recognizable frontier landmarks, political realities, and peoples. These symbols were presented to frontier children, to prepare them for their unavoidably racially violent future.

The Yellow Brick Road represents the yellow brick gold at the end of the Bozeman Road to the Montana gold fields. Chief Red Cloud had forced the razing of several posts, including Fort Phil Kearney and had forced the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty. When George Armstrong Custer cut "the Thieves' Road" during his 1874 gold expedition invasion of the sacred Black Hills, he violated this treaty and turned U.S. foreign policy toward the Little Big Horn and the Wounded Knee massacre.

The Winged Monkeys are the Irish Baum's satire on the old Northwest Mounted Police, who were modelled on the Irish Constabulary. The scarlet tunic of the Mounties and the distinctive "pillbox" forage cap with the narrow visor and strap are seen clearly in the color plate in the 1900 first edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Villagers across the Dakota territory heartily despised these British police, especially after 1877, when Sitting Bull retreated across the border and into their protection after killing Custer.

The Shifting Sands, the Deadly Desert, the Great Sandy Waste, and the Impassable Desert are Frank Baum's reference to that area of the frontier known always as "the great American desert," west and south of the Great Lakes. Baum creates these fictional, barren areas as protective buffers for his Oz utopia, against hostile, foreign people. This "buffer state" practice had been part of U.S. foreign policy against the Indians, since the earliest colonial days.

The Emerald City of Oz recreates the Irish nationalist's vision of the Emerald Isle, the sacred land, Ireland, set in this American desert like the sacred Paha Sapa of the Lakota people, these mineral-rich Black Hills floored by coal. Irish settlements in the territories, in Kansas, Nebraska, and Minnesota — at Brule City, Limerick, at Lalla Rookh, and at O'Neill two hundred miles south of Aberdeen — founded invasions of the Black Hills.

The Yellow Winkies, slaves, are Frank Baum's symbol for the sizeable Chinese population in the old West, emigrated for the Union-Pacific railroad, creatures with the slant or winking eyes.

The Deadly Poppy Field is the innocent child's first sight of opium, that anodyne of choice for pain in the nineteenth century, sold in patent medicines, in the Wizard Oil, at the travelling Indian medicine shows. Baum's deadly poppies are the poison opium, causing sleep and the fatal dream.

The Wicked Witch of the West is illustrated in the 1900 first edition as a pickaninny, with beribboned, braided pigtails extended comically. Baum repeats the word "brown" in describing her. But this symbol's real historic depth lies in the earlier Puritans' confounding of European witches with the equally heathen American Indians.

The orphan Dorothy's violent removal from Kansas civilization, her search for secret and magical cures for her friends, her capture, enslavement to an evil figure — and the killing of this figure that is forced on her — all these themes Baum takes from the already two hundred year old tradition of the Indian captivity narrative which stoked the fires of Indian-hating and its hope of "redemption through violence."

In the year immediately following the huge success of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Baum wrote and published a fantasy titled The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus. It is apparent that his frontier experiences were still on his mind. The book was illustrated by Mary Cowles Clark — tomahawks, spears, the traditional hide-covered teepees, and the faces of obviously Indian men, women, and children, and papooses fill the pages and their margins. Baum describes the "rude tent of skins on a broad plain."

Two crucial chapters are titled "The Wickedness of the Awgwas" and "The Great Battle Between Good and Evil." The Awgwas represent native Americans: "that terrible race of creatures" and "the wicked tribe." Baum condemns the "Awgwas," which is the backwards spelling of "Sawgwa," the medicine man, or holy man:

"You are a transient race, passing from life into nothingness. We, who live forever, pity but despise you. On earth you are scorned by all, and in Heaven you have no place! Even the mortals, after their earth life, enter another existence for all time, and so are your superiors." Predictably enough, a few pages later, "all that remained of the wicked Awgwas was a great number of earthen hillocks dotting the plain." Baum is recalling newspaper photos of the burial field at Wounded Knee.

The Wizard of Oz in 1899 ruling his empire from behind his Barrier of Invisibility evokes the 1869 Imperial Wizard of the Invisible Empire of the South, the Ku Klux Klan. Baum's figure, King Crow, and his by-play with the Scarecrow relate to the Jim Crow lynch law at the turn of the century.

Lyman Frank Baum's overwhelmingly popular fantasy, and the more violent aspects of United States foreign policy, were welded together in the American mind for the next century and beyond.

Frank Baum's widow, at the Hollywood premiere of The Wizard of Oz in 1939, complained that the story had been sentimentalized. Indeed, the old and crudely direct political symbols had been removed and the sweetness poured in — the new U.S. foreign policy demanded more subtle justifications.

In Studies in Classic American Literature, D.H. Lawrence observes that Benjamin Franklin has a specious equation:

Rum + Savage = 0

Lawrence asks the telling question, to which we are still bound following our invasions of other nations:

"But is a dead savage naught?"

In the weeks before and after the massacre at Wounded Knee, Frank Baum printed his editorials calling for the total extermination of all Indians remaining in the United States and its territories. These editorials may be seen at the most accurate website of Professor A. Waller Hastings: www.northern.edu/hastingw/baumedts.htm

Thomas St. John graduated from Drew University in Madison, New Jersey, and lived in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts. He has published in the University of Utah's Western Humanities Review and in the Ball State University Forum. A free-lance writer since 1971, his major publication is Forgotten Dreams: Ritual in American Popular Art (New York: The Vantage Press, 1987), a collection of essays on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The House of the Seven Gables, Reverend Jonathan Edwards' Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, the black history driving the films Casablanca and the cartoon The Three Little Pigs, and the Dakota Indian territory symbols in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Thomas St. John is also completing a popular history of Brattleboro, Vermont and is researching a biography of Dr. John Wilson, the highwayman known as "Captain Thunderbolt" of the original "Thunderbolt and Lightfoot."

Comment: Ireland, Mounties, coolies, and opium? Why not blacks, buffalo, trains, and the US Army? The alleged symbols are too random and unconnected to persuade me, but St. John's thesis is nonetheless provocative.

Editorials were no exception

Some people may try to rationalize Baum's editorials. They may speculate that someone ordered him to publish them, or that he had to pander to public sentiment or lose subscribers. But let's see what he wrote about minorities in his fiction:

Thomas St. John has summarized one of Baum's stories, The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, above. I haven't seen the original edition, but St. John claims the illustrations make it clear the "Awgwas" are supposed to be Indians. Maybe so.

The text itself refers only to the Awgwas being a tribe. They're located in the land of Ethop, which sounds African to me. In any case, Baum portrays the Awgwas as inhuman and evil. He clearly advocates genocide against these fictional tribesmen:

I do not like to mention the Awgwas, but they are a part of this history, and can not be ignored. They were neither mortals nor immortals, but stood midway between those classes of beings. The Awgwas were invisible to ordinary people, but not to immortals. They could pass swiftly through the air from one part of the world to another, and had the power of influencing the minds of human beings to do their wicked will.

They were of gigantic stature and had coarse, scowling countenances which showed plainly their hatred of all mankind. They possessed no consciences whatever and delighted only in evil deeds.

Their homes were in rocky, mountainous places, from whence they sallied forth to accomplish their wicked purposes.

The one of their number that could think of the most horrible deed for them to do was always elected the King Awgwa, and all the race obeyed his orders. Sometimes these creatures lived to become a hundred years old, but usually they fought so fiercely among themselves that many were destroyed in combat, and when they died that was the end of them. Mortals were powerless to harm them and the immortals shuddered when the Awgwas were mentioned, and always avoided them. So they flourished for many years unopposed and accomplished much evil.

I am glad to assure you that these vile creatures have long since perished and passed from earth; but in the days when Claus was making his first toys they were a numerous and powerful tribe.

"What shall we do?" asked Ak.

"These creatures are of no benefit to the world," said the Prince of the Knooks; "we must destroy them."

"Their lives are devoted only to evil deeds," said the Prince of the Ryls. "We must destroy them."

"They have no conscience, and endeavor to make all mortals as bad as themselves," said the Queen of the Fairies. "We must destroy them."

"They have defied the great Ak, and threaten the life of our adopted son," said beautiful Queen Zurline. "We must destroy them."

The Master Woodsman smiled.

"You speak well," said he. "These Awgwas we know to be a powerful race, and they will fight desperately; yet the outcome is certain. For we who live can never die, even though conquered by our enemies, while every Awgwa who is struck down is one foe the less to oppose us. Prepare, then, for battle, and let us resolve to show no mercy to the wicked!"

In addition to the Santa Claus story, the following suggests Baum meant what he said in his editorials. In his American Fairy Tales, in a story titled "The Box of Robbers," he wrote:

The three wicked ones groaned aloud and Beni said, in a hollow voice:

"I hope they will kill us quickly and not put us to the torture. I have been told these Americans are painted Indians, who are bloodthirsty and terrible."

"'Tis so!" gasped the fat man, with a shudder.

True, Baum put these words in the mouth of a villain. Still, it was an authorial choice Baum didn't have to make. That he used Indians as an analogy for barbarism suggests his mindset as well as the villain's.

Here are more examples of Baum's racism from Eric P. Gjovaag's excellent FAQ on Oz:

Books of Wonder has been criticized by some for altering two of its reprints of Baum's books. The original versions contained depictions that were seen as amusing in Baum's day, but times change, and they are now seen as offensive African or African-American stereotypes. In The Patchwork Girl of Oz, there is a living phonograph that plays a song that originally contained the line "Ah wants mah Lulu, mah coal-black Lulu;" this was changed to "Ah want my Lulu, mah cross-eyed Lulu" by Books of Wonder. (A later, similar line not only kept the change from coal-black to cross-eyed, it changes loves to the more grammatically correct love.) Later in the same book, the travelers meet a band of creatures called Tottenhots, an obvious play on the Hottentot tribe of Africa. Some references to these people's dusky skin color and other aspects of their appearance were edited or removed, and one picture of a Tottenhot was deleted. In Rinkitink in Oz, another picture of a Tottenhot was removed. Both pictures unflatteringly showed the Tottenhots as stereotypical savage Africans. Fortunately, none of these changes affect the stories at all, and many Oz fans accept them as necessary in today's world. (Others, of course, do not.)

Baum's racism defended

Gjovaag tries to defend Baum's racism with less than success:

Recently, some have accused L. Frank Baum of being a racist. While it's true that he advocated the extermination of the Lakota after the Battle of Wounded Knee, so did every other newspaper editor in the area at the time. and there are a few passages in some of his books that are not acceptible to many people today because of the depiction of certain ethnic groups. But Baum was raised in the 19th century, so it is not fair to judge him by the standards of the 21st. It is certainly not fair to compare him to Adolph Hitler, as some critics have done! In the next edition of the FAQ, I hope to present a balanced, objective examination of this issue.

Let's examine this defense:

>> While it's true that he advocated the extermination of the Lakota after the Battle of Wounded Knee, so did every other newspaper editor in the area at the time. <<

So other newspaper editors were racist also. Most Americans were stupidly, blindly prejudiced then. So? Baum was a racist and so were other newspaper editors and Americans. Is Gjovaag contesting the point or conceding it?

>> And there are a few passages in some of his books that are not acceptible to many people today because of the depiction of certain ethnic groups. <<

A few? So far Baum is batting 1.000. Judging by Gjovaag's evidence, every mention of minorities in Baum's writing is stereotypical and prejudiced.

>> But Baum was raised in the 19th century, so it is not fair to judge him by the standards of the 21st. <<

This argument is rubbish. As far back as the 1500s, priests like Bartolomé de Las Casas argued that treating Indians as subhumans—not to mention exterminating them—was wrong. Many Americans spoke favorably of Indians throughout the centuries. When the US Army massacred Indians in the West, newspapers reported the crimes, Easterners responded with outrage, and commissions investigated what happened.

Jackson book is telling

Helen Hunt Jackson was one of the most outraged at the US treatment of Indians, and she wrote a book, A Century of Dishonor, on the subject. Note that she wrote it in 1881, ten years before Baum's editorials. Here's what she said:

There is not among these three hundred bands of Indians one which has not suffered cruelly at the hands either of the Government or of white settlers. The poorer, the more insignificant, the more helpless the band, the more certain the cruelty and outrage to which they have been subjected. This is especially true of the bands on the Pacific slope. These Indians found themselves of a sudden surrounded by and caught up in the great influx of gold-seeking settlers, as helpless creatures on a shore are caught up in a tidal wave. There was not time for the Government to make treaties; not even time for communities to make laws. The tale of the wrongs, the oppressions, the murders of the Pacific-slope Indians in the last thirty years would be a volume by itself, and is too monstrous to be believed.

It makes little difference, however, where one opens the record of the history of the Indians; every page and every year has its dark stain. The story of one tribe is the story of all, varied only differences of time and place; but neither time nor place makes any difference in the main facts. Colorado is as greedy and unjust in 1880 as was Georgia in 1830, and Ohio in 1795; and the United States Government breaks promises now as deftly as then, and with an added ingenuity from long practice.

One of its strongest supports in so doing is the wide-spread sentiment among the people of dislike to the Indian, of impatience with his presence as a "barrier to civilization" and distrust of it as a possible danger. The old tales of the frontier life, with its horrors of Indian warfare, have gradually, by two or three generations' telling, produced in the average mind something like an hereditary instinct of questioning and unreasoning aversion which it is almost impossible to dislodge or soften....

So Baum, Mark Twain, and other Americans had average minds, while farsighted people like Jackson had minds advanced enough to see the hypocrisy of America's actions toward Indians. This despite the fact that all three were contemporaries. Then as now, people had enough information to form enlightened positions on social injustice. Then as now, people willfully ignored the information because it contradicted their belief in Anglo-American superiority.

Similarly, America faced a huge abolition movement against slavery in the 19th century, and Northerners were angry enough about the issue to go to war over it. To claim that everyone was prejudiced against blacks and Indians then and didn't know any better is a complete fiction. It's a modern person's way of excusing the inexcusable racism in his cherished icons.

See Those Evil European Invaders for more on how Europeans and Americans knew their actions were evil but committed them anyway.

The Hitler connection

>> It is certainly not fair to compare him to Adolph Hitler, as some critics have done! <<

Hitler advocated the extermination of Jews. Baum advocated the extermination of Indians. The difference is, Hitler had the means and opportunity to carry out his wishes. Baum didn't.

I don't know about other critics, but I've just stated the facts. Facts are neither fair nor unfair. Gjovaag should deal with them rather than trying to deny them.

>> In the next edition of the FAQ, I hope to present a balanced, objective examination of this issue. <<

One wonders how Gjovaag will "balance" Baum's explicit call for genocide. Let's see: Baum favored death for Indians but life for Anglos, so the Anglo survival rate balanced the Indian extermination rate? The so-called balance is hard to imagine.

I liked Venables's essay because he made the connection between America's and Hitler's genocidal policies. The connection is clear, which is why I wrote Adolf Hitler: A True American. Hitler may have killed more Jews than Americans killed Indians intentionally, but Americans pursued genocide as a cultural imperative over several hundred years. Their attitude was remarkably Hitler-like.

More on Baum and Oz

My Baum interview

Ozians just like Indians

Twisted Footnote to Wounded Knee (original posting)

Wizard of Oz—Frequently Asked Questions

Related links

Mark Twain, Indian hater

Is Huck Finn racist?

Savage Indians

Uncivilized Indians

Readers respond

"Starting with a fictional Baum doesn't seem like a productive way to understand the impulses behind Baum's fiction, if that's the goal."

"You've showed yourself as an ignorant racist and a fan of advocates of genocide. Period."

"The jumbling of the supposed allegorical equivalents in Baum's story actually works against the case that there is allegory going on."

"One thing that could be said about Baum's Oz was it was truly multicultural."

Gjovaag: "Baum's Oz books generally champion the value of folks learning to live together."

"Baum = Rape of Nanking? I have it! Baum = the Bubonic Plague!"

"The site's quotation from American Fairy Tales is also a stretch."

Pseudo-Indian story "The Enchanted Buffalo" doesn't prove Baum appreciated minorities.

"The article on L. Frank Baum was the biggest load of malarky I've ever read in my entire existence."

"What Baum published were the opinions of a frightened young family man."

|

. . . |

|

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.