Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

Smashing People: The "Honor" of Being an Athlete

(10/31/01)

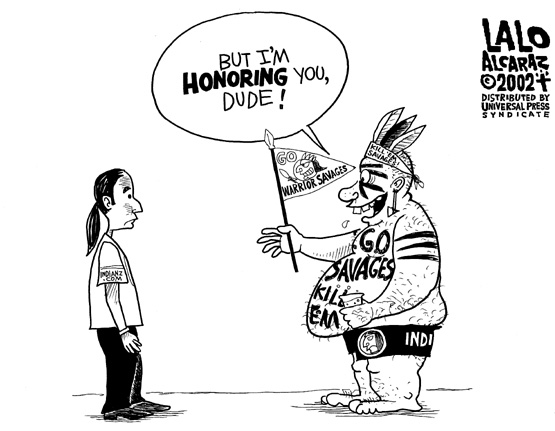

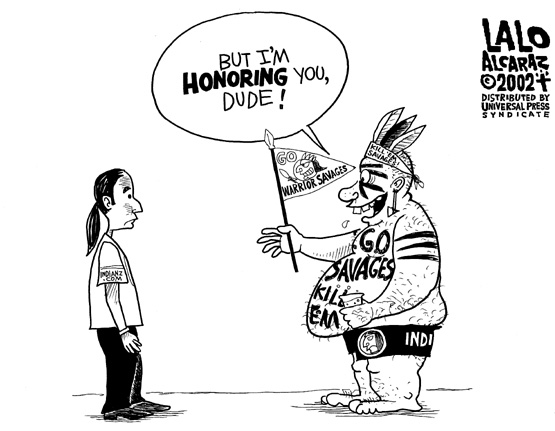

Athletes on sports teams with Indian names and mascots often say they're "honoring" Native people. Any basic treatise on mascots will tell you Indians don't accept, appreciate, or want the so-called honor. Let's turn the question around and see why.

Athletes on sports teams with Indian names and mascots often say they're "honoring" Native people. Any basic treatise on mascots will tell you Indians don't accept, appreciate, or want the so-called honor. Let's turn the question around and see why.

Should Native people feel honored by the association with athletes? What athletic attributes are Indians supposed to embrace? Here's an indicator from an LA Times report on a Southern California high school football team, 10/26/01:

The game program contains 28 mini-bios of Lakewood Mayfair High players. One question asked of all was, "What do you enjoy most about football?"

Eleven answered, in some form, "Hitting."

Ibrahim Atalla said, "The violence and when we score."

Danny Baker said, "Smashing people."

Jonathan Mercado said, "The feeling you get when you just flat-back someone."

And Kenneth Sutton II said, "Hitting, hitting and more hitting." [1]

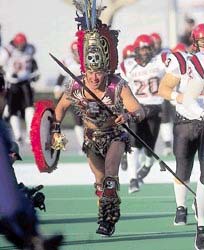

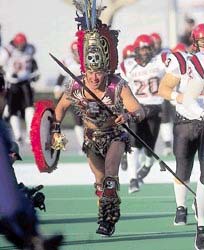

Whether they're called Trojans, Aztecs, or Fighting Illini, athletes aren't thinking about "honoring" the people they're named for. They're thinking about hitting and maiming—hard enough to give players concussions. So the claims of mascot supporters are false. These supporters may think it's an honor to name their teams after Indians, but their violent game-playing doesn't honor Indians. The athletes' actions are brutal and thuggish—i.e., savage.

Athletes themselves say they aren't in the game to achieve some lofty warrior ideal. They're in the game for the macho head-bashing and mindless aggression. Is that something Indians should feel honored by?

Do fans think any differently from the athletes they cheer for? One article suggests the answer is no. From the Hartford Courant:

School Panel Puts Off Vote On Mascot

February 10, 2006

By JESSE LEAVENWORTH, Courant Staff Writer

CANTON — Canton High School students papered school walls and windows Thursday with copies of their current "Dancing Warrior" mascot, expressing disappointment with a proposed new image they say waters down the school's fighting spirit.

The board of education, which has been wrestling with the issue for seven months, had planned to vote on whether to accept the latest warrior image Thursday night. But several board members said they either would not approve the image or were not ready to vote, and some Canton High students told the board they felt left out of the process of choosing a symbol that represents them.

In the end, the board decided to gather more information from students, who are to meet in a schoolwide assembly and focus groups.

The current angry-eyed warrior wears a full headdress and wields a hatchet. The proposed new symbol for the school's sports teams is a much more realistic representation of a Connecticut Indian, but he holds no weapon in his extended hands. Many students found that the image failed to convey the necessary fighting spirit, Kyle Martin, student representative to the school board, said outside the meeting. Students were especially unimpressed with the proposed warrior's stance, Martin said.

"It's not something you could use to intimidate," he said.

As everyone thought, the key issue is how violent and warlike the Indian mascot is, not how "noble" or "honorable" it is. An Indian who isn't intimidating people with a weapon is no Indian at all.

Indian warriors and football "warriors"

Who are the real-life "warriors" Indian warriors are supposed to be honored by? From Steve Lopez's column in the LA Times, 8/29/01:

POINTS WEST

A Sick Game That Celebrates Savagery

By STEVE LOPEZ, Times Staff Writer

My future as a professional football player got derailed one day in tryouts for my high school team.

It wasn't the heat that did me in, although it was as hot as hell's hinges. And it wasn't the stink, although you could faint from the smell of sweat-soaked pads and polyester jerseys.

What pushed me over the edge was our coach. We were in the middle of a blocking drill when he blew up, screaming like a lunatic until his eyes looked like they might pop out of his head. We were blocking like sissies, he foamed. Then he went up to a chain-link fence and exploded into it over and over again, head first, until his face was a bloody mess. When he turned to us, glaring with a madness that filled his every fiber, he said, "That's how you block, gentlemen."

When I quit, it wasn't because I was surprised that the coach was a psychopath. It was because I wasn't surprised.

Football is savage and dangerous, and it celebrates and markets those qualities without apology. It's a game for bullies and sociopaths, the more violent and eccentric the better. And they all go into it accepting pain, paralysis and worse, as part of the bargain. That's what a man does, because he's a man, even if it means he stands a good chance of limping away from the game crippled and maimed, his bell rung so many times he couldn't tie his shoes even if he could find them.

Sportswriter Mike Penner confirms that modern, win-at-all-costs football players have little in common with traditional Indian warriors who won victories by counting coup. From the LA Times, 9/3/01:

Unlike baseball and its press-pass-carrying bad poets society, football has never tried to pass itself off as a metaphor for life. Football, from the football perspective, is much bigger than that. It is the immovable object, the irresistible force. It views itself as modern-day siege warfare, combat and conquest, run by too many coaches and administrators who have read Sun Tzu's "The Art of War" and view themselves as caretakers of a sacred gladiator tradition handed down from the great armies of antiquity.

Where's the honor?

Football is the nation's premier sport. So what's the public perception of football players? That these athletes are often in it for the glory, the prestige, or the money. That they often use performance-enhancing drugs and bend or break the rules. That they rarely do well academically if they're in school, missing the whole point of education.

This suggests why Native people protest mascots but not "honors" like the Apache military helicopter or the Tomahawk missile. The latter, at least, associate them with real warriors—the soldiers and sailors who defend our country. Indians have always been proud to serve in America's military—despite the military's shameful role in oppressing their ancestors.

Athletes aren't warriors like our soldiers, who fight and sacrifice to serve and protect us. They're headbanging hulks who enjoy hurting their opponents. They use their skills and "savagery" for entertainment purposes—to win pointless games. [2]

America's me-first, win-at-all-costs mentality goes against everything most Native cultures hold dear. Since Indians traditionally eschew competition for competition's sake, why would they want to be associated with American sports? Most of them weren't warriors, they were peaceful villagers or nomads. Being labeled warlike when you're not warlike is no joy.

Indians live modern lives like the rest of us, yet they're tarred with the "savage" stereotype. Along with Western movies, sports mascots are a prime reinforcer of this notion. Generations of Americans have learned Indians are the outsider, the enemy, the "other." Native doctors, lawyers, and CEOs must cringe when they see themselves depicted as weapon-wielding maniacs.

Does a Native teacher, poet, or human rights advocate really want to be linked to a half-naked warrior caricature? If I had an investment club or a sewing circle, I wouldn't name it the "Gladiators" or "Bruisers" or "Jocks." The "honor" of being associated with athletes is decidedly one-way. The athletes may benefit, but Indians don't.

Warriors are losers, ultimately

Tom Holm, author of Strong Hearts, Wounded Souls: Native American Veterans of the Vietnam War, offers a key argument:

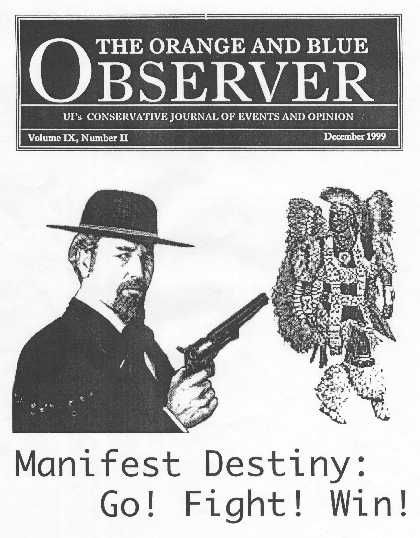

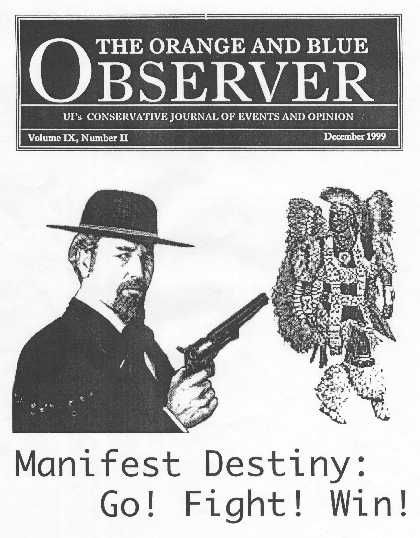

[W]hen the local high school football team named "the Braves," or "the Chiefs," or "the Indians," charges onto the field behind a mascot bearing the name "Chief Yoyo" or "the fighting Apache," the fans in the stands are not "honoring" Indians, they are really celebrating the American myth that says these brave, savage warriors were overcome only by white American tenacity, skill, and courage.

Writing about the Chief Illiniwek mascot, D. Anthony Tyeeme Clark (Meskwaki) makes a similar point:

When read through the lens of an American Indian-centered history, so-called "Chief" Illiniwek is a tragic hero, a defeated "warrior" and spiritual guide who offers a cathartic reproof of his ancestors' past injustices. Huddleston's chief is an example of imperialist nostalgia, a widespread tactic used by colonial powers like Australia, Canada, the United States, and New Zealand to cover up domination and transform those responsible for the oppression of indigenous peoples (including American Indians) to act as innocent bystanders.

These arguments echo what I've said before: The stereotype of the Native warrior is one-dimensional. Indians fought nobly. They lost. Now we enshrine them on the sports field as a bunch of noble losers.

The one-dimensional warrior-athlete stereotype confirms everything mainstream Americans believe. That Indians had no real civilization or culture. That they deserved to lose because they could only fight—because they couldn't assimilate and become good Christians like the rest of us. That nothing except their warrior skills is worth remembering.

In short, that they were brutes, barbarians, savages—unmatched at mayhem, to be sure, but failures otherwise.

We memorialize ferocious beasts—lions and tigers and bears—as sports teams. And in reality, we shoot them, cage them, or wipe out their habitats because they're an obstacle to civilization. We memorialize "savage" Indians for the same reason: because we, the full-fledged people of destiny, are better than them, the one-dimensional warrior losers.

That's about what a mascot is. It's a museum piece, a trophy on the wall, a monument to a vanquished people. Why would anyone want to be associated with that?

Mascots obscure history

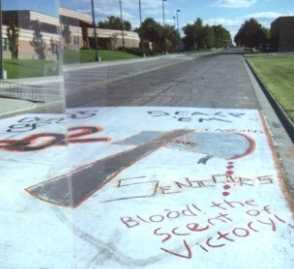

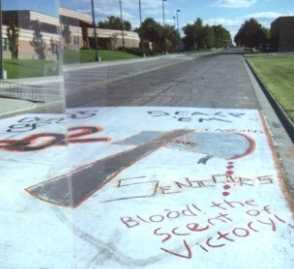

Not only does the Indian mascot stereotype Native people, it distorts and trivializes Native history. When people see Indians merely as warriors, they don't realize the complex forces that led to America's Indian Wars. They assume the issues were pretty simple: white civilization vs. Indian barbarism. High-minded pioneers and settlers vs. ignorant savages. Creators vs. destroyers.

Mascots obscure this history further by supporting the white-American status quo. They're willing participants in the staged drama of a sports contest, a ritualized conquest. No need to feel bad, mascots seem to be saying to fans. Indians are dancing and celebrating just like everyone else in the stadium.

In "Racism and Ignorance" (Inside Higher Education, 8/9/05), Carol Spindel elaborates on this point:

The strong attachment students feel for their mascots or nicknames is not instinctual; it is promoted. Students are indoctrinated into a campus cult of racial stereotyping. Critical thinking on the subject of the mascot must be discouraged and the school has to promote an anti-educational, anti-intellectual reaction. This is even more disturbing because it takes place in a setting of talk about "honoring" Indians. But Indian mascots are fantasy figures, firmly stuck in the past.

One parallel symbol is Aunt Jemima, the slave cook who loved the plantation so much she didn't want to leave when she was freed. She is a white fantasy that denies and betrays the real history of slavery, just like the mascot Osceola. The real Osceola fought against American expansion into Seminole land and was betrayed when he came in good faith to a peace council with American soldiers. But his mascot reincarnation is happy to welcome Florida State fans.

Knowing this history, Native people find it hard to explain to us why mascots are so offensive. We can't hold up our end of the argument. It's like the modern teenager who looks at the Aunt Jemima syrup bottle, sees a positive depiction of a smiling African-American grandmother, and says, "What's the problem? It's so positive."

The problem isn't this particular logo, but the long pattern of denying the history of slavery that the original Aunt Jemima, with the ads depicting her life history, represents. In addition to slavery, there is another reality we have swept under our historical carpet: how we acquired this land we love so much. When you sweep something that large under the rug, you get bumps. Mascots are bumps in our historical carpet, something we are trying to rearrange and deny to make it more appealing. In our version of the story, American Indians just disappeared and our mascots commemorate them with respect and honor.

Why not these warriors?

If sports teams want a name that really kicks butt, how about something from Hitler's Nazis: the Panzers or Luftwaffe or Blitzkrieg? How about the Kamikazes? The Viet Cong? The Terrorists?

You won't see any of these as American team names. Why not? Because these names actually subvert rather than support the American mythos. These "warriors" kicked our butts for a time. They won or almost won their wars.

In other words, they were a little too savage, fierce, and determined. They made Americans and Europeans look bad. We don't want to celebrate that.

No, we celebrate only safe "warriors." Animals that we can cage or shoot if they get uppity. "Ancient" battlers (Trojans and Spartans or Mohawks and Apaches) that we can "honor" and dismiss as irrelevant today. Seen in that light, why would Indians appreciate the so-called honor? Who wants to be remembered as a relic of the past?

How about a real honor?

From Darken Up, A-Hole: Reflections on Indian Mascots and White Rage (8/10/05) by Tim Wise, recounting a barroom discussion with a mascot fan:

"Yeah but what really galls me," he continued, "is that a bunch of these schools are just trying to honor Native Americans. They're just trying to pay respect to the spirit of the Indians. It's like nothing we can do is ever enough for those people."

Aside from how calling indigenous folks "those people" jibes with a true desire to honor them (let alone his claim to be one at some remove), this particular nugget—offered by far more than just one drunk guy at a Nashville bar—has always struck me as especially vile.

If schools wanted to honor first nations people, after all, they could do it in any number of more meaningful ways. They could establish Native American studies programs and fund them adequately. They could step up their recruitment of Indian students, staff and faculty, rather than retreating from such efforts in the face of misplaced backlash to affirmative action. They could strip the names off of buildings on their campuses that pay tribute to those who participated in the butchering of Native peoples. Here in Nashville that process could begin by renaming, without delay, any building named after Andrew Jackson, of which there are several.

Perhaps most importantly, we could begin by telling the truth about what was done to the indigenous of this land, rather than trying to paper over that truth, minimize the horror, and, once again, change the subject. You know the kind of people I'm speaking of: the ones who refuse to label the elimination of over ninety-five percent of the native peoples of the Americas "genocide."

Final thoughts on the "honor" argument

From the Ann Arbor News:

Carty: Indian mascot schools should look in mirror

Sunday, August 7, 2005

BY JIM CARTY

News Sports Columnist

Can't they see the obvious? The Chippewas, Seminoles, Fighting Illini and Savages of college sports are all just honoring those tribes or their area's Indian heritage.

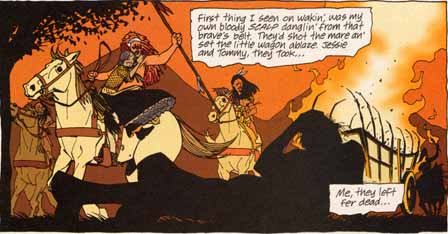

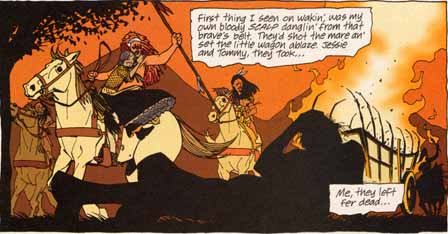

Without Southeastern Oklahoma State athletics working to change its image, what hope do the Savages have of being seen in a positive light? Everywhere you look in the media, it's Savages attacking the wagon train or Savages scalping settlers.

.

.

.

When white kids wearing Indian costumes -- often pointedly described as authentic Indian costumes on school Web sites, because, you know, that's a whole lot different from your average Halloween Tonto getup -- well, when those white kids dance at halftime of Illinois games or charge on to the field on a horse before a Florida State football game, they're spreading the message that ...

Well, there's a message in there, trust me.

Endnotes

[1] The LA Times article continues:

Fred Hayes Jr., a former Mayfair player who is a chiropractor and oversees the team's medical needs, said parents, players and coaches all need to be more vigilant about responding to players' head injuries, no matter how minor they might seem.

"I think parents don't realize the impact of those ... they are brain injuries," Hayes said. "It's not just, 'My kid got his bell rung.' No, your kid got his brain impacted against the inside of his skull."

Hayes added, "I think you can compare it to driving down the road at 25 mph and jumping out and tackling a mailbox."

It isn't just Hayes's opinion that playing football is equivalent to crashing in a car. Studies have shown this to be true. From "Study: Football Hits Similar to Crashes" in the Associated Press, 1/3/04:

Football players were struck in the head 30 to 50 times per game and regularly endured blows similar to those experienced in car crashes, according to a Virginia Tech study that fitted players' helmets with the same kinds of sensors that trigger auto air bags.

Let's recap: Mayfair is just your "normal" all-American school—no Indian mascots or students that I know of. The LA Times article shows what your normal, all-American athletes are thinking when they play their games. Their athletic mindset is common, from what I've seen. What they're thinking is presumably the same whether they have a name like "Redskins" or "Braves" or not.

[2] It's not quite true that American sports are pointless. The point is to be the greatest: no. 1. "Winning isn't everything, it's the only thing." "Show me a good loser and I'll show you a loser." "Nice guys finish last."

Other countries tend to focus on an athlete's skill and grace, which is why individual sports such as track and field, swimming, and gymnastics are popular overseas. In the US it's all about earning bragging rights, being top dog. It's a classic example of the American mindset in action.

Related links

Team names and mascots

Savage Indians

Violence in America

Readers respond

Most people think athletes are noble and heroic figures. Indians should be happy to be associated with them.

* More opinions *

|

|

. . .

|

|

Home |

Contents |

Photos |

News |

Reviews |

Store |

Forum |

ICI |

Educators |

Fans |

Contests |

Help |

FAQ |

Info

All material © copyright its original owners, except where noted.

Original text and pictures © copyright 2007 by Robert Schmidt.

Copyrighted material is posted under the Fair Use provision of the Copyright Act,

which allows copying for nonprofit educational uses including criticism and commentary.

Comments sent to the publisher become the property of Blue Corn Comics

and may be used in other postings without permission.

Athletes on sports teams with Indian names and mascots often say they're "honoring" Native people. Any basic treatise on mascots will tell you Indians don't accept, appreciate, or want the so-called honor. Let's turn the question around and see why.

Athletes on sports teams with Indian names and mascots often say they're "honoring" Native people. Any basic treatise on mascots will tell you Indians don't accept, appreciate, or want the so-called honor. Let's turn the question around and see why.